Download Paper (PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The New Spirituality: Is It Selfish?

7/1/2009 Special Features Archive: The Ne… Special Features Archive Welcome to CLAL Special Features where you will find articles by guest columnists and roundtables on hot issues and special topics. Our authors are especially interested in hearing your responses to what they have written. So after reading, visit the Special Features Discussion. To join in conversation with CLAL faculty and other readers click here . To access the Special Features Archive, click here . The New Spirituality: Is it Selfish? -- A CLAL Roundtable Rabbi Arthur Hertzberg has ridiculed the new spirituality--including a popular interest in Kabbalah and the teachings of the Dalai Lama--as a "fad" that is "self-centered," as distinguished from Jewish values that "impel us to make life more bearable for others." Political scientist Charles Liebman describes spirituality as a "privatized religion....Its emphases are interpersonal rather than collective." We asked CLAL faculty to talk about spirituality, and the conflicts, if any, between personal spiritual fulfillment and the collective Jewish experience. Scroll through all the responses or click on the authors' names to access individual responses. David Nelson Daniel Brenner Andrew Silow-Carroll Tsvi Blanchard David Nelson: Two very brief responses: 1) When I hear critiques such as those of Hertzberg and Liebman I wonder http://www.clal.org/sf6.html 1/6 7/1/2009 Special Features Archive: The Ne… what might be at stake under the surface. In this particular case, I wonder if there is an element of "ownership-anxiety" in this debate. What I mean is that some religious institutions, and those who are deeply affiliated with or loyal to them, sometimes criticize any religious experience or movement which they do not own. -

New York City (3)” of the Sheila Weidenfeld Files at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 26, folder “6/22/76 - New York City (3)” of the Sheila Weidenfeld Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 26 of the Sheila Weidenfeld Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON R~'--~~e. t) ~ ~R\. June 18, 1976 ~p_L.. ~u'-le. \i MEMORANDUM TO: FROM: SUBJECT: The following event has been added to Mrs. Ford's June 22nd trip to New York City: EVENT: Dedication of the Martin Steinberg Center of the Stephen Wise Congress House GROUP: American Jewish Congress DATE: Thursday, June 22, 1976 TIME: To be determined (4:00-6:00 p.m.) PLACE: Martin Steinberg Center J.J.;<:rO 15 East 84th Street New York, New York CONTACT: Mr. Richard Cohen, Associate Executive Director 0: (212) 879-4500 H: (212) 988-8042 COMi."1.ENTS: As you know, Mrs. Ford will participate in the dedication of the Martin Steinberg Center at the time of her trip to New York to attend the Jewish National Fund dinner at the New York Hilton Hotel. -

A History of Antisemitism Fall 2019

A History of Antisemitism Fall 2019 Dr. Katherine Aron-Beller Tel Aviv University International [email protected] _____________________________________________________________________ An analysis of articulated hatred toward Jews as a historical force. After treating precursors in the pagan world of antiquity and in classical Christian doctrine, the course will focus on the modern phenomenon crystallizing in 19th-century Europe and reaching its lethal extreme in Nazi ideology, propaganda, and policy. Expressions in the U.S. and in the Arab world, as well as Jewish reactions to antisemitism, will also be studied. Course Outline 1. Wednesday 23td October: Antisemitism – the oldest hatred Gavin Langmuir, Toward a Definition of Antisemitism. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990)pp. 311-352. Peter Schäfer, Judaeophobia: Attitudes Toward the Jews in the Ancient World. Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1997, pp. 34-64, 197-211. 2. Monday 28th October: Jews as Christ Killers – the deepest accusation New Testament (any translation): Matthew 23; 26:57-27:54; John 5:37-40, 8:37-47 John Chrysostom, Discourses Against Judaizing Christians, Homily 1 at: www.fordham.edu/halsall/source/chrysostom-jews6.html Marcel Simon, Verus Israel. Oxford: Littman Library, 1986, pp. 179-233. 3. Wednesday 30th October: The Crusades: The First Massacre of the Jews Soloman bar Samson: The Crusaders in Mainz, May 27, 1096 at: www.fordham.edu/halsall/source/1096jews-mainz.html Robert Chazan, “Anti-Jewish violence of 1096 – Perpetrators and dynamics” in Anna Sapir Abulafia Religious Violence between Christians and Jews (Palgrave, 2002) Daniel Lasker, “The Impact of the Crusades on the Jewish-Christian debate” Jewish History 13, 2 (1999) 23-26 4. -

124900176.Pdf

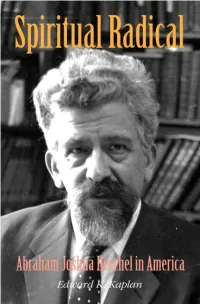

Spiritual Radical EDWARD K. KAPLAN Yale University Press / New Haven & London [To view this image, refer to the print version of this title.] Spiritual Radical Abraham Joshua Heschel in America, 1940–1972 Published with assistance from the Mary Cady Tew Memorial Fund. Copyright © 2007 by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Set in Bodoni type by Binghamton Valley Composition. Printed in the United States of America by Sheridan Books, Ann Arbor, Michigan. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Kaplan, Edward K., 1942– Spiritual radical : Abraham Joshua Heschel in America, 1940–1972 / Edward K. Kaplan.—1st ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-300-11540-6 (alk. paper) 1. Heschel, Abraham Joshua, 1907–1972. 2. Rabbis—United States—Biography. 3. Jewish scholars—United States—Biography. I. Title. BM755.H34K375 2007 296.3'092—dc22 [B] 2007002775 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. 10987654321 To my wife, Janna Contents Introduction ix Part One • Cincinnati: The War Years 1 1 First Year in America (1940–1941) 4 2 Hebrew Union College -

Personal Material

1 MS 377 A3059 Papers of William Frankel Personal material Papers, correspondence and memorabilia 1/1/1 A photocopy of a handwritten copy of the Sinaist, 1929; 1929-2004 Some correspondence between Terence Prittie and Isaiah Berlin; JPR newsletters and papers regarding a celebration dinner in honour of Frankel; Correspondence; Frankel’s ID card from a conference; A printed article by Frankel 1/1/2 A letter from Frankel’s mother; 1936-64 Frankel’s initial correspondence with the American Jewish Committee; Correspondence from Neville Laski; Some papers in Hebrew; Papers concerning B’nai B’rith and Professor Sir Percy Winfield; Frankel’s BA Law degree certificate 1/1/3 Photographs; 1937-2002 Postcards from Vienna to I.Frankel, 1937; A newspaper cutting about Frankel’s meeting with Einstein, 2000; A booklet about resettlement in California; Notes of conversations between Frankel and Golda Meir, Abba Eban and Dr. Adenauer; Correspondence about Frankel’s letter to The Times on Shylock; An article on Petticoat lane and about London’s East End; Notes from a speech on the Jewish Chronicle’s 120th anniversary dinner; Notes for speech on Israel’s prime ministers; Papers concerning post-WW2 Jewish education 1/1/4 JPR newsletters; 1938-2006 Notes on Harold Wilson and 1974 General Election; Notes on and correspondence with Oswald Mosley, 1966 Correspondence including with Isaiah Berlin, Joseph Leftwich, Dr Louis Rabinowitz, Raphael Lowe, Wolfe Kelman, A.Krausz, Norman Cohen and Dr. E.Golombok 1/1/5 Printed and published articles by Frankel; 1939, 1959-92 Typescripts, some annotated, for talks and regarding travels; Correspondence including with Lord Boothby; MS 377 2 A3059 Records of conversations with Dr. -

Palestine and Transjordan in Transition (1945–47)

Chapter 1 Palestine and Transjordan in Transition (1945–47) 1 Framing the Background 1.1 “Non possumus”? The Alternate Relations between the Holy See and the Zionist Movement (1897–1939) At the turn of the twentieth century, the Holy See’s concern about the situation of Catholics in the eastern Mediterranean was not limited to the rivalry among European powers to achieve greater prominence and recognition in Jerusalem. By the end of the nineteenth century, a new actor had appeared on the scene: the Jewish nationalist movement, Zionism, whose significance seemed to be on the increase all over Europe after it had defined its program and as the num- ber of Jews emigrating to Palestine after the first aliyah (1882–1903) became more consistent.1 The Zionist leaders soon made an attempt at mediation and rapproche- ment with the Holy See.2 Indeed, the Vatican’s backing would have been 1 From the vast bibliography on Zionism, see, in particular, Arturo Marzano, Storia dei sion- ismi: Lo Stato degli ebrei da Herzl a oggi (Rome: Carocci, 2017); Walid Khalidi, From Haven to Conquest: Readings in Zionism and the Palestine Problem until 1948, 3rd ed. (Washington, DC: Institute for Palestine Studies, 2005); Alain Dieckhoff, The Invention of a Nation: Zionist Thought and the Making of Modern Israel, trans. Jonathan Derrick (New York: Columbia University Press, 2003); Georges Bensoussan, Une histoire intellectuelle et politique du sionisme, 1860–1840 (Paris: Fayard, 2002); Walter Laqueur, A History of Zionism (New York: Schocken, 1989); Arthur Hertzberg, ed., The Zionist Idea: A Historical Analysis and Reader (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1959). -

At the Crossroads: Shaping Our Jewish Future

At the Crossroads: Shaping Our Jewish Future Jonath;m D. Sarna THE FL~URE OF AMER ' ~ ICAN JEWISH COMMUNITY" Combined Jewish Philanthropies Wilstein Institute of Jewish Policy Studies 1995 Dreaming the Future of the American Jewish Community JONATHAN D. SARNA "Dreall/s arc ltal 50 dl((erwl (rom Deeds as some mav 111I1Ik. Alllhe Deeds o( melt ,7 r t' :'Izl\' DrWI1l5 m {Irs I. Alld in Ihe eltd, Ihelr Deeds dls50/\'e into DrCi7II15," -TiIEODOR IlERZL ALT\ElU\D (t.:J c':') CU nting in 1964, the dean of American Jewish histori ans, Jacob R. Marcus, anticipated the future of the American Jewish community with boundless optimism, "A new Jew is ... emerging here on American soil, n he exulted. "Blending ... Americanism and Judaism," this new Jew, he believed, would preside over "the birth of another Golden Age in Jewish life. n "Barring a Ihistorical accident'," he wrote, "such a development IS inevitable on this soiL" Three decades later, such optimistic predictions ring hollow to many American Jews. Instead, the literature of American Jewish life is suffused with pessimism. "In recent years, n the National Jewish Popula tion Survey found, "just over half of Born Jews who married ... chose a spouse who was born a Gentile and has remained so." Without a spiritual revival, Arthur Hertzberg warns, "American Jewish history will soon end, and become a part of American memory as a whole." Against this background, the Wilstein Institute's call for visionary lead ership (" As you think about the American Jewish community of the fu ture, describe the kind of community you would like to see") is particu larly welcome. -

Directories Lists Necrology National Jewish Organizations1

Directories Lists Necrology National Jewish Organizations1 UNITED STATES Organizations are listed according to functions as follows: Religious, Educational 305 Cultural 299 Community Relations 295 Overseas Aid 302 Social Welfare 323 Social, Mutual Benefit 321 Zionist and Pro-Israel 326 Note also cross-references under these headings: Professional Associations 334 Women's Organizations 334 Youth and Student Organizations 335 COMMUNITY RELATIONS Gutman. Applies Jewish values of justice and humanity to the Arab-Israel conflict in AMERICAN COUNCIL FOR JUDAISM (1943). the Middle East; rejects nationality attach- 307 Fifth Ave., Suite 1006, N.Y.C., 10016. ment of Jews, particularly American Jews, (212)889-1313. Pres. Clarence L. Cole- to the State of Israel as self-segregating, man, Jr.; Sec. Alan V. Stone. Seeks to ad- inconsistent with American constitutional vance the universal principles of a Judaism concepts of individual citizenship and sep- free of nationalism, and the national, civic, aration of church and state, and as being a cultural, and social integration into Ameri- principal obstacle to Middle East peace, can institutions of Americans of Jewish Report. faith. Issues of the American Council for Judaism; Special Interest Report AMERICAN JEWISH COMMITTEE (1906). In- stitute of Human Relations, 165 E. 56 St., AMERICAN JEWISH ALTERNATIVES TO N.Y.C., 10022. (212)751-4000. Pres. May- ZIONISM, INC. (1968). 133 E. 73 St., nard I. Wishner; Exec. V. Pres. Bertram H. N.Y.C., 10021. (212)628-2727. Pres. Gold. Seeks to prevent infraction of civil Elmer Berger; V. Pres. Mrs. Arthur and religious rights of Jews in any part of 'The information in this directory is based on replies to questionnaires circulated by the editors. -

(I) the Five Jewish Influences on Ramah

THE JACOB RADER MARCUS CENTER OF THE AMERICAN JEWISH ARCHIVES MS-831: Jack, Joseph and Morton Mandel Foundation Records, 1980–2008. Series C: Council for Initiatives in Jewish Education (CIJE). 1988–2003. Subseries 5: Communication, Publications, and Research Papers, 1991–2003. Box Folder 42 2 Fox, Seymour, and William Novak. Vision at the Heart. Planning and drafts, February 1996-May 1996. For more information on this collection, please see the finding aid on the American Jewish Archives website. 3101 Clifton Ave, Cincinnati, Ohio 45220 513.487.3000 AmericanJewishArchives.org FROM: "Dan Pekarsky", INTERNET:[email protected] TO: Nessa Rapoport, 74671,3370 Nessa Rapoport, 74671,3370 DATE: 2/5/96 10:19 AM Re: Ramah and my paper Sender: [email protected] Received: from audumla.students.wisc.edu (students.wisc.edu [144.92.104.66]) by dub-img-4.compuserve.com (8.6.10/5.950515) id JAA22229; Mon, 5 Feb 1996 09:56:41 -0500 Received: from mail.soemadison.wisc.edu by audumla.students.wisc.edu; id IAA111626 ; 8.6.9W/42; Mon, 5 Feb 1996 08:56:40 -0600 From: "Dan Pekarsky" <[email protected]> Reply-To: [email protected] To: [email protected], [email protected] Date: Sun, 04 Feb 1996 21 :12:00 -600 Subject: Ramah and my paper X-Gateway: iGate, (WP Office) vers 4.04m - 1032 MIME-Version: 1.0 Message-Id: <[email protected]> Content-Type: TEXT/PLAIN; Charset=US-ASCII Content-Transfer-Encoding: ?BIT Nessa, I am finding the in-progress Ramah piece very interesting, and I'm struck by the number of times my own intuitive reactions are mirrored a few lines down by your own comments in the brackets. -

Ordination of the 100Th Graduate of the Israeli Rabbinical Program

power, in print, broadcast, and social media, Israel is a country awash with ORDINATION “ and in hospital rooms and family moments. rabbis. What difference can one They provide leadership, solace, support, OF THE hundred more make? A great difference. and vision. They are part of a remarkable We find graduates of HUC-JIR’s Israeli movement of Jewish renewal currently Rabbinical Program at some of the most 100TH unfolding - alongside all the challenges and significant settings within Israeli society. conflicts - in contemporary Israel. From the GRADUATE OF They serve as leaders in informal and border with Lebanon to the shores of the Red formal education; as school principals THE ISRAELI Sea, in makeshift structures and impressive and directors of early childhood education edifices, this first one hundred is preparing RABBINICAL systems. They run large institutions, and the groundwork for the hundreds to follow bring congregations to life around Israel. PROGRAM in their illustrious footsteps. They have Their voices are heard in the corridors of established congregations and institutions, ISRAELI RABBINICAL PROGRAM: In the Footsteps of “My classmates grew up secular, 11 Generations Orthodox, or religious Reform, are of different ages and from different places of Rabbis in Israel, but found their center in Reform ideology. I value the connection RABBI LEORA with the North American students EZRAHI-VERED ’17 worshipping and studying with us. It is very meaningful to form friendships with colleagues who will be leaders throughout Israel and around the world, so that our communities will one day EDUCATION: ■ Granddaughter of Rabbi Wolfe Kelman, become friends too.” B.A. -

CONSERVATIVE JUDAISM: Volume XVIII, Number 1, Fall 1963 Published by the Rabbinical Assembly. EDITOR: Samuel H. Dresner. DEPARTM

TO sigh Oo1 to h the able AU, the ham Yaw prec CONSERVATIVE JUDAISM: Volume XVIII, Number 1, Fall 1963 Published by The Rabbinical Assembly. Sha~ a fe EDITOR: Samuel H. Dresner. to '" MANAGING EDITOR: jules Harlow. con' BOOK REVIEW EDITOR: jack Riemer. focu wen DEPARTMENT EDITORS: Max Routtenberg, David Silvennan. peri EDITORIAL BOARD: Theodore Friedman, Chairman; Walter Ackerman, Philip A rian, Solomon Bernards, Ben Zion Bokser, Seymour Fox, Shamai Kanter, fron Abraham Karp, Wolfe Kelman, jacob Neusner, Fritz Rothschild, Richard sent Rubenstein, 1\Jurray Schiff, Seymour Siegel, Andre Ungar, Mordecai Waxman, the Max Wahlberg. to o hap] of tl OFFICERS OF THE RABBINICAL ASSEMBLY: Rabbi Theodore Friedman, President; Rabbi Max j. Routtenberg, Vice-President; Rabbi S. Gershon Levi, Treas men urer; Rabbi Seymour j. Cohen, Recording Secretary; Rabbi jacob Kraft, hose Corresponding Secretary; Rabbi Max D. Davidson, Comptroller; Rabbi Wolfe cons Kelman, Executive Vice-President. wha gard pres• CONSERVATIVE JUDAISM is a quarterly publication. The subscription fee is $3.00 per year. Application for second class mail privileges is pending at New York, SIOn N.Y. All articles and communications should be addressed to the Editor, Andr 979 Street, Springfield, Mass.; subscriptions to The Rabbinical 3080 Broadway, New York 27, N.Y. TO BIRMINGHAM, AND BACK ANDRE UNGAR THERE WAS no special emphasis in the way that group of Jews murmured, sighed, chanted its way through the ancient benediction of "Blessed are You, 0 our eternal God, Who help a man walk uprightly," but perhaps there ought to have been. It was, to all appearances, a simple case of morning worship; the stylish dining room in which it took place presented a rather unremark able setting for the occasion. -

Who's Who Im World Jewry First International Conference Jerusalem Founders Assembly the Jewish Hall of Fame

WHO'S WHO IM WORLD JEWRY FIRST INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE JERUSALEM FOUNDERS ASSEMBLY THE JEWISH HALL OF FAME PATRON The Honorable Ephraim Katzir December 20 1976 President of the State of Israel Office of the President and EDITORIAL BOARD Chairman of the Editorial Board Dr. I. J. Carmin Karpman I. J. Carmin Karpman Chairman Mr. Artur Rubinstein,Pianist Virtuoso General Editor 22 Sq de L’Avenue Foch, The Standard Jewish Encyclopedia Paris, I6l eme, Anatole A. Yaron Executive Director, Who's Who in World Jewry France Dr. Avraham Avi-hai, Jerusalem Lecturer, Political Science Bar Ilan University Mr. Irving Bernstein, New York Executive' Vice Chairman United Jewish Appeal Dear Sir: Dr. Israel Bilecky, Tel Aviv Lecturer, Yiddish Literature Tel Aviv University Mr. Solon Myles Chadabe, New York Member, Board of Directors You are cordially invited to join the Honorary Advisory Board of National Federations of Temple Brotherhoods the proposed JEWISH HALL OF FAME to be established in Jerusalem Mr. Bernard Cherrick, Jerusalem Vice President under the auspices of WHO’S WHO IN WORLD JEWRY. Panels of experts Hebrew University are being constituted to plan the monumental JEWISH HALL OF FAME Mr. Seymour Fishman, New York Executive Vice President as a repository of Jewish heritage and knowledge and as an expression American Friends of the Hebrew University of the Jewish contribution to the progress of mankind in all fields Mr. Arnold Forster, New York General Counsel, Anti-Defamation of human endeavor. League of B'nai B'rith Mr. Bertram H. Gold, New York The President of Israel, the Honorable Professor Ephraim Katzir, Executive Vice President The American Jewish Committee Patron of WHO’S WHO IN WORLD JEWRY, endorsed the project, stating: Mr.