View a Preview of the Proceedings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Year in U.S. Occupational Health & Safety (7Th

The Year in U.S. Occupational i Health & Safety Fall 2017 – Summer 2018 7th Edition By Celeste Monforton, DrPH, MPH & Kim Krisberg Labor Day, 2018 The Year in U.S. Occupational Health & Safety: 2012 Report Kim Krisberg is a freelance writer who specializes in public health. She was on the staff of the American Public Health Association and continues to write for the association’s newspaper, the Nation’s Health. She contributes several times a week to The Pump Handle blog. Celeste Monforton, DrPH, MPH, is project director of Beyond OSHA and a lecturer in the Department of Health and Human Performance at Texas State University. She contributes weekly to The Pump Handle blog. The authors thank Liz Borkowski, MPH, for her editorial assistance. The full-page photos in the yearbook were taken on Dec. 5-7, 2017 at the National Conference on Worker Safety and Health in Baltimore, MD (COSHCON17). Appearing is: Chee Chang, International Brotherhood of Teamsters (IBT); Ella Ellerbe, UFCW Local 1208 in Tar Heel, NC; Kayla Kelechian, Worker Center of Central New York; Manuel Pérez, Cincinnati Interfaith Workers Center; Jim Moran, PhilaPOSH; and Steve Kreins, BLET 236/ IBT in Portland, OR. This report was produced with funding from the Public Welfare Foundation, but the views expressed in it are those of the authors alone. Graphic Design: TheresaWellingDesign.com Table of Contents Introduction and Overview I. The Federal Government and Occupational Health and Safety ......................... 1 OSHA, MSHA, and NIOSH ................................................................................................................3 Poultry and Meatpacking Workers Challenge USDA Policies .................................................... 10 Chemical Safety Board and EPA ................................................................................................... 14 II. Addressing Occupational Health and Safety at the State and Local Levels .. -

N E W S & N O T

THE FIRE BELL CLUB OF NEW YORK, INC. Organized February 10, 1939 204 EAST 23rd STREET NEW YORK, N.Y. 10010–4628 Phone: 212–448–1240 www.firebellclub.org VOLUME 44, NO. 3 MARCH, 2011 BELL CLUB NEWS Mussorfiti (ret.). They helped shape haz-mat response into a series of mission-specific The April 12 speaker will be Assistant competencies which have become the Chief Ronald Spadafora, Chief of Logistics. countryʹs standard. The Annual Dinner will be held June 9th Chief Del Re continued with a presentation and the annual visit to the Shops will be on the history and current status of the June 14. Please remember that the visit to N FDNYʹs Haz-Mat Tiered response. From the Shops is restricted to members only or a 1982 to 1984, Rescue Four of Queens handled member plus guest. E A reminder. The Clubʹs email group is for haz-mat incidents. On December 3, 1984, club membersʹ use only. If you are going to however, there was a major accident at the forward mail to a non member, please Union Carbide Plant in Bhopal, India. Thirty W utilize your personal email address and to 40 tons of methyl isocyanate (MIC) were delete all references to the clubʹs email released as a vapor cloud. Despite the highly address and other information regarding S our membership. In addition, if you wish to toxic nature of MIC, there was no pre- reply to a member in the group who sends incident plan and local responders were not out an email, do not use the group address; called. -

A Letter from the President

A Letter from the President It is my pleasure to introduce you to John Jay College of Criminal Justice. Educating for justice is our mission. To accomplish this, we o˜ er a rich liberal arts education focusing on the themes of fairness, equity and justice. We encourage robust debate on the critical issues facing our society, promote rigor in thinking and writing, and foster deep understanding of the human condition. We celebrate the diversity of our student body. Our 14,000 students re°e ct the broad diversity of New York City itself, including di˜ erent races, ethnic groups, ages, nationalities, religions and career interests. We consider John Jay a close-knit community, global in outlook, located on the West Side of Manhattan. In this bulletin, you will learn about the undergraduate degrees that we o˜ er in 20 criminal-justice related majors. ˛ ese challenging programs meet the highest academic and professional standards. ˛ ey prepare you for a wide range of careers and lay a foundation for graduate studies or law school. Learning about these subjects at John Jay is at once thought-provoking and exciting because of our faculty. John Jay faculty are recognized experts in their areas of scholarship. Many are engaged in research projects around the world. Our faculty bring their real world experiences into the classroom. ˛ e faculty at John Jay enjoy fostering the academic success of their students. ˛r ough this unique combination of distinguished faculty and innovative curriculum, we endeavor to prepare you to become ethically and socially responsible leaders for the global community. -

January 2015 Attrition Mitigation Newsletter.Pub

The RecruiterJANUARY 2015 INSIDE THIS FDNY Officers Get Sworn In ISSUE: FDNY Pays Tribute to Dr. King Learn the Latest Firefighter Stats FDNY Fire Commissioner Daniel Nigro, fourth from left, and Chief of Department James Leonard, center, congrat- ulated the officers during the swearing-in ceremony on Firefighter Jan. 30. From left are Chief of EMS Communications An- 101 thony Napoli; Chief of Training Stephen Raynis; Deputy Fire Commissioner, Chief Diversity and Inclusion Officer Pamela Lassiter; Chief of Operations John Sudnik; Chief FDNY HS of EMS James Booth; Assistant Chief of EMS Michael Alumni to Fitton and Chief of Fire Prevention Ronald Spadafora. Serve in The FDNY celebrated the future on Jan. 30, Dispatch swearing in the first-ever Chief Diversity and In- clusion Officer and promoting six senior Fire and EMS officers at FDNY Headquarters. Story continues on page 2 PAGE 2 THE RECRUITER FDNY Officers Get Sworn In Story continued from previous page The officers were applauded as the ceremony came to a close on Jan. 30. “These men and women will help us move forward in a new and exciting direction,” said Fire Commissioner Daniel Nigro. During the ceremony, Pamela Lassiter was sworn in as Deputy Fire Commissioner, Chief Diversity and Inclusion Officer. In addition, six chiefs were promoted, including John Sudnik to Chief of Operations, Stephen Raynis to Chief of Training, Ronald Spadafora to Chief of Fire Prevention, James Booth to Chief of EMS, Michael Fitton to Assistant Chief of EMS and Anthony Napoli to Chief of EMS Communications. “They make us so much stronger as a Department,” Chief of Department James Leonard said. -

Fire Dep't V. Egan, OATH Index No

Fire Dep't v. Egan, OATH Index No. 819/97 (Aug. 15, 1997), aff’d sub nom Egan v. Von Essen, 260 A.D.2d 479, 688 N.Y.S.2d 573 (2d Dep’t 1999). Summary : 1.Admissions made by respondent regarding injuries and plan to cover them up with a work related accident related by two co-workers, which were unexplained by respondent, sufficient proof of misconduct. Petitioner presented evidence from two co-workers who were totally credible that respondent told them he had injured himself at a jujitsu class and planed to cover it up as a work-related injury for a better pension. Circumstantial evidence that respondent sustained an injury during a jujitsu injury produced was also produced through another co-worker. Absent any explanation for the admissions made by respondent, the evidence permits a conclusion that respondent injured himself off duty and falsely claimed to have incurred that injury at work. CHARLES D. McFAUL, Administrative Law Judge This disciplinary proceeding was referred to me pursuant to section 15-113 of the Administrative Code and section 75 of the Civil Service Law. Petitioner, the Fire Department, charged that Firefighter Richard Egan, the respondent, filed false reports with the Department and the Fire Department Pension Fund. The charges alleged that respondent falsely claimed to have sustained injuries while at work on May 10, 1993, when in fact he was injured at a jujitsu class while off duty (ALJ Ex. 1). Respondent denied that he was injured at a jujitsu class and maintained that his injuries and resulting disabilities were work related. -

November-2016

TO: Fr. Gary Sharky and Fr. Mike Hovsepian of Engine 70 and all the other members of Engine 70 and Ladder 53 for organizing the plaque dedication for Fr. John J. Daly who died from injuries sustained on October 1, 1954 at Bronx Box 4526. He died on June 12, 1955. Also honored was Fr. Peter J. Bradley of Ladder 53. He died in the line-of-duty on July 18, 1955 of a heart attack. TO: Fr. Brian Hennelly, Mike Hettwer, and Dominic Dimino of Engine 42 who organized the Mass at the quarters of Engine 42 to commemorate the 10th anniversary of the fire that claimed the lives of Fr. Michael Reilly, Engine 75 and Lieutenant Howard Carpluk of Engine 42. TO: Engine 90 and Ladder 41 for hosting the annual Memorial Day collation. There was an excellent turnout for Memorial Day. TO: Those who stepped up and participated in the annual Mutual Aid Drill with Westchester County Fire Departments. 101 Chrystie Street was a 7-story Multiple Dwelling at the corner of Chrystie and Grand Streets. It was constructed of brick and wood joist and it was 80 foot x 80 foot. In the center of the building, there was an air and light shaft. The night tour of January 24, 1998 started innocently enough in the Chinatown section of Lower Manhattan. It was the time of year when the Chinese New Year was being celebrated. Fireworks could be heard going off all over the neighborhood. It was a cold night; the Officer in Engine 9 was Lieutenant Bob Burns. -

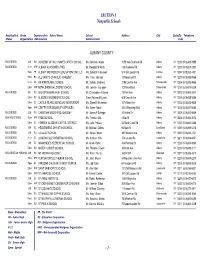

SECTION I Nonpublic Schools

SECTION I Nonpublic Schools Registration Grade Incorporation School Name School Address City StateZip Telephone Status Organization Abbreviation Administrator Code ALBANY COUNTY REGISTERED JSH RO ACADEMY OF HOLY NAMES-UPPER SCHOOL Mrs. Michele Musto 1075 New Scotland Rd Albany NY 12208 (518)438-7895 REGISTERED K-12 NFP ALBANY ACADEMIES (THE) Mr. Douglas M North 135 Academy Rd Albany NY 12208 (518)429-2300 Elem FP ALBANY MONTESSORI EDUCATION CTR, LLC Ms. Deborah A Boswell 514 Old Loudon Rd Cohoes NY 12047 (518)250-4401 Elem RO ALL SAINTS' CATHOLIC ACADEMY Ms. Traci Johnson 10 Rosemont St Albany NY 12203 (518)438-0066 K-12 EC AN NUR ISLAMIC SCHOOL Mr. Sohaib Chekima 2195 Central Ave Schenectady NY 12304 (518)395-9866 Elem NFP BETHLEHEM CHILDRENS SCHOOL Ms. Jennifer Congdon 12 Fisher Blvd Slingerlands NY 12159 (518)478-0224 REGISTERED SH RO BISHOP MAGINN HIGH SCHOOL Mr. Christopher A Signor 75 Park Ave Albany NY 12202 (518)463-2247 Elem RO BLESSED SACRAMENT SCHOOL Sister Patricia M Lynch 605 Central Ave Albany NY 12206 (518)438-5854 Elem EC CASTLE ISLAND BILINGUAL MONTESSORI Ms. Diane M Nickerson 10 N Main Ave Albany NY 12203 (518)533-9838 Spec NFP CENTER FOR DISABILITY SERVICES Ms. Karen Macri 314 S Manning Blvd Albany NY 12208 (518)437-5685 REGISTERED JSH RO CHRISTIAN BROTHERS ACADEMY Mr. James P Schlegel 12 Airline Dr Albany NY 12205 (518)452-9809 NON REGISTERED Elem NFP FREE SCHOOL Ms. Tershia Ellis 8 Elm St Albany NY 12202 (518)434-3072 Elem EC HEBREW ACADEMY-CAPITAL DISTRICT Ms. Julie Pollack 54 Sand Creek Rd Albany NY 12205 (518)482-0464 REGISTERED JSH EC HELDERBERG CHRISTIAN SCHOOL Mr. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Agency names below link to relevant pages: Actuary, Office of the Administration of Children’s Services Administrative Tax Appeals, Office of Administrative Trials and Hearings, Office of Aging, Department for the Board of Elections Borough President, Bronx Borough President, Brooklyn Borough President, Manhattan Borough President, Queens Borough President, Staten Island Buildings, Department of Business Integrity Commission Campaign Finance Board Chief Medical Examiner, Office of City Clerk City Council Citywide Administrative Services, Department of Civil Service Commission Civilian Complaint Review Board Collective Bargaining, Office of Commission on Human Rights Comptroller, Office of Conflicts of Interest Board Consumer Affairs, Department of Correction, Department of Cultural Affairs, Department of Design and Construction, Department of District Attorney, Bronx District Attorney, Brooklyn District Attorney, Queens Economic Development Corporation Education, Department of Emergency Management, Office of Environmental Protection, Department of Equal Employment Practices Commission Finance, Department of Financial Information Services Agency Fire Department Franchise Concession Review Committee Health + Hospitals Health and Mental Hygiene, Department of Homeless Services, Department of Housing Authority Housing Development Corporation Housing Preservation and Development, Department of Human Resources Administration Independent Budget Office Information Technology and Telecommunications, Department of Investigation, -

LAST CALL CONFERENCES in ENGLISH Simultaneous Translation Service English / Spanish

LAST CALL CONFERENCES IN ENGLISH Simultaneous Translation Service English / Spanish BARCELONA, 18-20 November 2013 EURO MEDITERRANEAN conference on WILDFIRE PROMOTED by: Consorci Universitat Internacional Menéndez Pelayo de Barcelona In COLABORATION with: Instituto de Seguridad Pau Costa Foundation Pública de Cataluña SPONSORED by: Centro Tecnológico Joint Research European Forest Tecnosylva Forestal de Cataluña Centre Institute CHAIRMAN: GENERAL COORDINATION: Jordi Vendrell Mariona Borràs Pau Costa Foundation Pau Costa Foundation Área de I+D Área de Administración #EUfire 2 REGISTRATION Follow the link: www.cuimpb.cat [email protected] Place Aula 1 Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona (CCB) Montalegre, 5. Barcelona LANGUAGE English / Spanish There will be simultaneous translation service University Certificate Recognized Secretaria de Alumnos Tel. 933 017 555 [email protected] Conference degree recognized by: Catalonian Civil Protection Service Institute #EUfire 3 @ www.cuimpb.cat www.paucostafoundation.org www.gencat.cat/interior/ispc/ facebook.com/cuimpb facebook.com/PauCostaFoundation #EUfire More information [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] CONFERENCE WEB SITE – more information: paucostafoundation.org Cover photograph thomassmithphotography.com #EUfire 4 EURO MEDITERRANEAN conference on WILDFIRE TABLE of CONTENTS Organizers and collaborations 6 Pau Costa Foundation President Welcome 7 Speakers 8 Schedule 12 • Workshop sessions information 15 #EUfire 5 Organizers and collaborations Consorci Universitat Internacional Menéndez Pelayo de Barcelona. The CUIMPB – Centre Ernest Lluch is tasked with managing the permanent campus of the Menéndez Pelayo International University (UIMP) in Barcelona. The UIMP’s celebrated university campus coordinates and develops UIMP activities around culture, research, and specialized training, bringing together students and faculty from various university degrees and courses of specialization. -

2009-2010 Undergraduate Bulletin

undergraduategraduate bulletinbulletin 2009 2009 – 2010 – 2010 A Letter from the President It is my pleasure to introduce you to John Jay College of Criminal Justice. Educating for justice is our mission. To accomplish this, we offer a rich liberal arts education focusing on the themes of fairness, equity and justice. We encourage robust debate on the critical issues facing our society, promote rigor in thinking and writing, and foster deep understanding of the human condition. We celebrate the diversity of our student body. Our 14,000 students reflect the broad diversity of New York City itself, including different races, ethnic groups, ages, nationalities, religions and career interests. We consider John Jay a close-knit community, global in outlook, located on the West Side of Manhattan. In this bulletin, you will learn about the undergraduate degrees that we offer in 20 criminal justice-related majors. These challenging programs meet the highest academic and professional standards. They prepare you for a wide range of careers and lay a foundation for graduate studies or law school. Learning about these subjects at John Jay is at once thought-provoking and exciting because of our faculty. John Jay faculty are recognized experts in their areas of scholarship. Many are engaged in research projects around the world. Our faculty bring their real world experiences into the classroom. The faculty at John Jay enjoy fostering the academic success of their students. Through this unique combination of distinguished faculty and innovative curriculum, we endeavor to prepare you to become ethically and socially responsible leaders for the global community. -

Graduate Bulletin

Bulletin JOhn Jay COllege This Bulletin is neither a contract nor an offer to contract between the College and any person or party; thus the College reserves the right to make additions, deletions, and modifications to curricula, course descriptions, degree requirements, academic policies, schedules and academic calendars, financial aid policies, and tuition and fees without notice. All changes take precedence over Bulletin statements. While reasonable effort will be made to publicize changes, students are encouraged to seek current information from appropriate offices because it is the responsibility of the student know and observe all applicable regulations and procedures. No regulation will be waived or exception granted because students plead ignorance of, or contend that they were not informed of, the regulations or procedures. The College reserves the right to effect changes without notice or obligation including the right to discontinue a course or group of courses or a degree program. Although the College attempts to accommodate the course requests of students, course offerings may be limited by financial, space, and staffing considerations or may otherwise be unavailable. Students are strongly encouraged to schedule an appointment with their advisor at least once each semester, preferably before registering for the upcoming term. A Letter from the President Thank you for considering the graduate programs of John Jay College of Criminal Justice. A world leader in educating for justice since 1964, John Jay offers a rich liberal arts and professional studies curriculum to a diverse and highly motivated student body. At John Jay, we define justice in our teaching and research both narrowly, with an eye toward meeting the needs of criminal justice and public service agencies, and broadly, in terms of enduring questions about fairness, equality and the rule of law. -

Fire Department City of New York

FIRE DEPARTMENT CITY OF NEW YORK 9 MetroTech Center Brooklyn, NY 11201-3857 Janet Kimmerly, Editor 718-999-1455 (phone); 718-999-0704 (fax) Photo by FF Michael Gomez, Squad 288 Queens Box 88-2211, 95-20 150th Street/95th Avenue, January 17, 2011. Welcome to WNYF, WITH NEW YORK FIREFIGHTERS, the official training publication of the New York City Fire Department. WNYF is distributed four times per year (quarterly) and contains technical and practical articles for those involved in the fire service. Oriented to those directly involved in fire operations and fire safety, WNYF is geared toward individuals routinely engaged in providing firefighting services. In publication since 1940, WNYF continues the tradition of providing quality articles expected from this world-class fire magazine. Articles planned for the 2nd/2011 issue include “Runs & Workers for 2010,” compiled by Captain John Regan; “Medal Day Winners for 2010”; “July 1, 2010, Brooklyn Box 55-0816,” by Deputy Assistant Chief Michael Marrone, Staten Island Borough Commander; “December 10, 2010, Manhattan Box 22-0926 (blown standpipe, fire blanket deployed, improvisation),” by Deputy Chief Joseph Carlsen and Battalion Chief Thomas Meara; “Summer/Fall 2010 Hurricane/Tornado Activity,” by Assistant Chief Ronald Spadafora and Deputy Chiefs Jon Malkin and Charles Clarke; “Deploying the FDNY Task Force Teams,” by Deputy Assistant Chief Robert Maynes; “Rooftop Challenges & Remedies,” by Battalion Chief John J. Salka, Jr.; “Chauffeur’s Corner,” by Lieutenant Paul Schmalzreid; “Lessons Learned at September 2, 2010, Bronx Box 66-3848,” by Deputy Chief Ronald Werner; “Electric and Hybrid Cars—the Chevy Volt,” by Lieutenant Michael Doda; and “The Learning Curve,” by Captain Stephen Marsar and Lieutenant Christopher Flatley.