1 ~ the Long Coregency Revisited: Architectural And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Canaan Or Gaza?

Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections Pa-Canaan in the Egyptian New Kingdom: Canaan or Gaza? Michael G. Hasel Institute of Archaeology, Southern Adventist University A&564%'6 e identification of the geographical name “Canaan” continues to be widely debated in the scholarly literature. Cuneiform sources om Mari, Amarna, Ugarit, Aššur, and Hattusha have been discussed, as have Egyptian sources. Renewed excavations in North Sinai along the “Ways of Horus” have, along with recent scholarly reconstructions, refocused attention on the toponyms leading toward and culminating in the arrival to Canaan. is has led to two interpretations of the Egyptian name Pa-Canaan: it is either identified as the territory of Canaan or the city of Gaza. is article offers a renewed analysis of the terms Canaan, Pa-Canaan, and Canaanite in key documents of the New Kingdom, with limited attention to parallels of other geographical names, including Kharu, Retenu, and Djahy. It is suggested that the name Pa-Canaan in Egyptian New Kingdom sources consistently refers to the larger geographical territory occupied by the Egyptians in Asia. y the 1960s, a general consensus had emerged regarding of Canaan varied: that it was a territory in Asia, that its bound - the extent of the land of Canaan, its boundaries and aries were fluid, and that it also referred to Gaza itself. 11 He Bgeographical area. 1 The primary sources for the recon - concludes, “No wonder that Lemche’s review of the evidence struction of this area include: (1) the Mari letters, (2) the uncovered so many difficulties and finally led him to conclude Amarna letters, (3) Ugaritic texts, (4) texts from Aššur and that Canaan was a vague term.” 12 Hattusha, and (5) Egyptian texts and reliefs. -

A Greek Inscription

A Greek Inscription: “Jesus is Present” of the Late Roman Period at Beth Loya by Titus Kennedy Introduction At the site of Khirbet Beth Loya, located in the Judean Hills east of Lachish and west of Hebron, a short but important ancient Greek inscription was carved into a rock wall of one of the underground caves. Although the ancient name of the site is unknown at this point, according to discoveries it was a prominent Christian site in the Byzantine period, and possibly earlier. The Byzantine church there is a single apse basilica that was erected ca. 500 AD, remained in use for over 200 years until it was apparently abandoned, and eventually the area was overtaken by a Muslim cemetery.1 Several elaborate mosaics, including Christian inscriptions, designs, and depictions of biblical scenes cover the church floor.2 The site, however, was also occupied earlier, in the Hellenistic and Roman periods.3 The Inscription During the Hellenistic and Roman periods, many subterranean installations were carved out of the soft rock on the site.4 In one of these subterranean caves near the Byzantine era church, an ancient Greek inscription mentions Jesus. The entrance to the cave is now obscured by foliage, but on the wall opposite the entrance, an inscription carved into the limestone can be plainly seen. The letters are much taller and deeper than is usual, which may indicate that it was meant to be plainly seen from anywhere in the small cave. The short inscription, which is all on one line, begins with a simple cross and reads ΙΕCΟΥC ΟΔΕ (or in miniscule ιεσους οδε). -

In Ancient Egypt

THE ROLE OF THE CHANTRESS ($MW IN ANCIENT EGYPT SUZANNE LYNN ONSTINE A thesis submined in confonnity with the requirements for the degm of Ph.D. Graduate Department of Near and Middle Eastern Civiliations University of Toronto %) Copyright by Suzanne Lynn Onstine (200 1) . ~bsPdhorbasgmadr~ exclusive liceacc aiiowhg the ' Nationai hiof hada to reproduce, loan, distnia sdl copies of this thesis in miaof#m, pspa or elccmnic f-. L'atm criucrve la propri&C du droit d'autear qui protcge cette thtse. Ni la thèse Y des extraits substrrntiets deceMne&iveatetreimprimCs ouraitnmcrtrepoduitssanssoai aut&ntiom The Role of the Chmaes (fm~in Ancient Emt A doctorai dissertacion by Suzanne Lynn On*, submitted to the Department of Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations, University of Toronto, 200 1. The specitic nanire of the tiUe Wytor "cimûes", which occurrPd fcom the Middle Kingdom onwatd is imsiigated thrwgh the use of a dalabase cataloging 861 woinen whheld the title. Sorting the &ta based on a variety of delails has yielded pattern regatding their cbnological and demographical distribution. The changes in rhe social status and numbers of wbmen wbo bore the Weindicale that the Egyptians perceivecl the role and ams of the titk âiffefcntiy thugh tirne. Infomiation an the tities of ihe chantressw' family memkrs bas ailowed the author to make iderences cawming llse social status of the mmen who heu the title "chanms". MiMid Kingdom tifle-holders wverc of modest backgrounds and were quite rare. Eighteenth DMasty women were of the highest ranking families. The number of wamen who held the titk was also comparatively smaii, Nimeenth Dynasty women came [rom more modesi backgrounds and were more nwnennis. -

The Last Demotic Inscription

The Last Demotic Inscription Eugene Cruz-Uribe In the course of my work at the temple of Isis on Philae The subject of this short paper is to return to the subject Island, I was able to record a number of new Demotic of what was the last Demotic inscription and offer a new graffiti.1 These graffiti were located in all areas of the tem- alternative in honor of Sven Vleeming so he may enjoy re- ple and I see them as a potentially significant addition to viewing this thesis and hopefully not include it as an entry the corpus of Demotic texts found at the temple. Griffith, in his next Berichtigungsliste volume. who published the first group of these texts,2 noted GPH Thus far it is certain that GPH 365 is the last dated 377, which is located on the roof of the pronaos of the Demotic inscription that has been recorded. In my study temple.3 That text was actually a pair of texts, one being a of the texts at Philae I have pondered the question of the short Demotic graffito and the other being a longer Greek placement of graffiti in the temple and how their loca- text. This text was considered to be the last Demotic graf- tion may give us additional information on why they were fito, as the companion Greek text was dated to 15 Choiak found where they were.8 In my examination of the temples year 169 = 11 December AD 452.4 GPH 365 is now consid- on Philae Island, I also considered my earlier thesis that ered the last Demotic text.5 In Griffith’s publication the the pious Egyptians had a tendency not to write graffiti in date of GPH 365 was read as 6 Choiak 169 = 2 December an ‘active’ portion of a temple.9 Thus I noted the location of AD 452.6 The date, however, has now been correctly many of the Demotic graffiti around Philae temple, but also reread as sw 16, which gives us a date of 12 December around many other temples that have Demotic (or other AD 452.7 ancient Egyptian) graffiti. -

Temples and Tombs Treasures of Egyptian Art from the British Museum

Temples and Tombs Treasures of Egyptian Art from The British Museum Resource for Educators this is max size of image at 200 dpi; the sil is low res and for the comp only. if approved, needs to be redone carefully American Federation of Arts Temples and Tombs Treasures of Egyptian Art from The British Museum Resource for Educators American Federation of Arts © 2006 American Federation of Arts Temples and Tombs: Treasures of Egyptian Art from the British Museum is organized by the American Federation of Arts and The British Museum. All materials included in this resource may be reproduced for educational American Federation of Arts purposes. 212.988.7700 800.232.0270 The AFA is a nonprofit institution that organizes art exhibitions for presen- www.afaweb.org tation in museums around the world, publishes exhibition catalogues, and interim address: develops education programs. 122 East 42nd Street, Suite 1514 New York, NY 10168 after April 1, 2007: 305 East 47th Street New York, NY 10017 Please direct questions about this resource to: Suzanne Elder Burke Director of Education American Federation of Arts 212.988.7700 x26 [email protected] Exhibition Itinerary to Date Oklahoma City Museum of Art Oklahoma City, Oklahoma September 7–November 26, 2006 The Cummer Museum of Art and Gardens Jacksonville, Florida December 22, 2006–March 18, 2007 North Carolina Museum of Art Raleigh, North Carolina April 15–July 8, 2007 Albuquerque Museum of Art and History Albuquerque, New Mexico November 16, 2007–February 10, 2008 Fresno Metropolitan Museum of Art, History and Science Fresno, California March 7–June 1, 2008 Design/Production: Susan E. -

The Karnak Hypostyle Hall Project Field Report 2004-2005 by Peter J

The Karnak Hypostyle Hall Project Field Report 2004-2005 By Peter J. Brand Introduction Collation of Facsimile Drawings of the Battle Reliefs of Ramesses II on the South Wall with Our field work was authorized by Egypt’s Su- Palimpsest of the Battle of Kadesh. preme Council of Antiquities and functioned with the cooperation of the Centre Franco-égyptien pour l’étude The main objective of the season was to com- des Temples de Karnak. We extend our thanks to our plete collation of war scenes on the south exterior wall other Egyptian and French colleagues: Dr. Zahi Hawas, of the Hypostyle Hall in order to produce facsimile President of the SCA, along with the entire Perma- drawings of these reliefs. Initial drawings of these war nent Committee which authorized our work. In Luxor, scenes were first made in 1995. We began collation of we are grateful to Mr. Ibrahim Sulliman, the Director the drawings in 1999 under the Project’s late director, of Karnak and Mr. Fawzy (our inspector); along with professor William J. Murnane. Our collation of the in- Nicolas Grimal and Emanuelle Laroche (scientific and scriptions on this wall was made more difficult by their field directors of the Centre). The expedition staff for poor state of preservation and the fact that part of the this season’s work included two epigraphists: the field wall is a palimpsest in stone with two sets of hieroglyph- director, Dr. Peter Brand of the University of Memphis, ic texts superimposed one atop the other. Tennessee and Dr. Suzanne Onstine from the Univer- sity of Arizona. -

Patterns of Evidence: Exodus Lesson 1 – Timeline Watch First 20 Minutes

Patterns of Evidence: Exodus Lesson 1 – Timeline Watch first 20 minutes on Right Now media Exodus Story – Biblical Summary ◦ Joseph moved his family to Egypt during the 7-year famine ◦ Israelites lived in the land of Goshen ◦ Years after Joseph died, a new pharaoh became fearful of the large numbers of Israelites. ◦ Israelites became slaves ◦ Moses was 80 when God sent him to Egypt to free the Israelites ◦ After Passover, the Israelites wandered in the desert for 40 years ◦ Israelites conquered the Promised Land An Overview of Egyptian History Problems with Egyptian History ◦ Historians began with multiple lists of Pharaoh’s names carved on temple walls ◦ These lists are incomplete, sometimes skipping Pharaohs ◦ Once a “standard” list had been made, then they looked at other known histories and inserted the list ◦ These dates then became the accepted timeline Evidence for the Late Date – 1250 BC • Genesis 47:11-12 • Exodus 18-14 • Earliest archaeological recording of the Israelites dates to 1210 BC on the Merneptah Stele o Must be before that time o Merneptah was the son of Ramses II • Ten Commandments and Prince of Egypt Movies take the Late Date with Ramses II Evidence for the Early Date – 1440 BC • “From Abraham to Paul: A Biblical Chronology” by Andrew Steinmann • 1 Kings 6:1 – Solomon began building temple 480 years after the Exodus o Solomon’s reign began 971 BC and began building temple in 967 BC o Puts Exodus date at 1447 BC • 1 Chronicles 6 lists 19 generations from Exodus to Solomon o Assume 25 years per generation – Exodus occurred -

Historic Graffiti: Teacher’S Notes Revised Oct

Historic Graffiti: Teacher’s Notes Revised Oct. 2017 Summary of the project The Norfolk Medieval Graffiti Survey was established to undertake the very first large-scale and systematic survey of medieval church inscriptions in the UK. The project was entirely volunteer led, supported by the Heritage Lottery Fund, and surveyed over 650 surviving medieval churches. The survey resulted in the recording of over thirty thousand previously unknown inscriptions, and the project received national recognition in the form of a number of awards. The success of the Norfolk project led to the establishment of a large number of similar projects in other counties across the UK. www.medieval-graffiti.co.uk [email protected] Carlisle Castle CONTENTS Document Structure This document contains background material on issues raised in the educational sheets produced as part of the Norfolk Medieval Graffiti Survey. The educational sheets contain a number of historic graffiti related activities and subjects for group discussion and debate. This document contains a number of suggestions for guiding and expanding those discussions, and suggestions for a number of group activities. A short glossary and bibliography at the end of the document should enable group leaders and students to expand their study and debate in all areas of historic graffiti. The document is split into four main sections. Section 1: Background - an introduction to the study of ancient graffiti, why we study it, and what it can tell us about the past. Section 2: Interpretation - a summary of the main types of graffiti encountered in historic churches and other buildings, with a brief explanation of the meaning of each type. -

Amarna Period Down to the Opening of Sety I's Reign

oi.uchicago.edu STUDIES IN ANCIENT ORIENTAL CIVILIZATION * NO.42 THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO Thomas A. Holland * Editor with the assistance of Thomas G. Urban oi.uchicago.edu oi.uchicago.edu Internet publication of this work was made possible with the generous support of Misty and Lewis Gruber THE ROAD TO KADESH A HISTORICAL INTERPRETATION OF THE BATTLE RELIEFS OF KING SETY I AT KARNAK SECOND EDITION REVISED WILLIAM J. MURNANE THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO STUDIES IN ANCIENT ORIENTAL CIVILIZATION . NO.42 CHICAGO * ILLINOIS oi.uchicago.edu Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 90-63725 ISBN: 0-918986-67-2 ISSN: 0081-7554 The Oriental Institute, Chicago © 1985, 1990 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. Published 1990. Printed in the United States of America. oi.uchicago.edu TABLE OF CONTENTS List of M aps ................................ ................................. ................................. vi Preface to the Second Edition ................................................................................................. vii Preface to the First Edition ................................................................................................. ix List of Bibliographic Abbreviations ..................................... ....................... xi Chapter 1. Egypt's Relations with Hatti From the Amarna Period Down to the Opening of Sety I's Reign ...................................................................... ......................... 1 The Clash of Empires -

Extraction and Use of Greywacke in Ancient Egypt Ahmed Ibrahim Othman

JFTH, Vol. 14, Issue 1 (2017) ISSN: 2314-7024 Extraction and Use of Greywacke in Ancient Egypt Ahmed Ibrahim Othman 1 Lecturer – Tourism Guidance Department Hotel Management and Restoration Institute, Abu Qir. [ Introduction The Quseir – Qift road was the only practical route in the Central Easter Desert as it was the shortest and easiest road from the Nile Valley to the Red Sea, in addition to the richness of the Bekhen stone quarries and the gold mines. Therefore, it was the preferred road by the merchants, quarrymen and miners. The Bekhen stone quarries of Wadi Hammamat forms an archaeological cluster of inscriptions, unfinished manufactures, settlements, workshops and remaining tools. It seems clear that the state was responsible for the Bekhen stone exploitation, given the vast amount of resources that had to be invested in the organization of a quarrying expedition. Unlike the other marginal areas, the officials leading the missions to Wadi Hammamat show different affiliations in terms of administrative branches. This is probably because Bekhen stone procurement was not the responsibility of the treasury, but these expeditions were entrusted to separate competent officials, graded in a specific hierarchy, forming well – organized missions with different workers for different duties and established wages and functionaries in charge of the administrative tasks. The greywacke quarries were not constantly or intensively exploited. The fact that the stone was used in private or royal statuary and not as a building stone could have caused its demand to be less than that of other materials such as granite, limestone or sandstone. Inscriptions indicated the time lapse between expeditions suggesting that this stone was only quarried when it was needed, which was not on a regular basis. -

The Neo-Babylonian Historical Setting for Daniel 7

Andrews University Seminary Studies, Spring 1986, Vol. 24, No. 1, 31-36. Copyright @ 1986 by Andrews University Press. THE NEO-BABYLONIAN HISTORICAL SETTING FOR DANIEL 7 WILLIAM H. SHEA Andrews University In a series of earlier studies on the historical chapters of Daniel, I have suggested that a number of details in those narratives can be correlated with events of the sixth century B.C. to a greater degree than has previously been appreciated.' In some instances, it is also possible to make a rather direct correlation between an historical narrative in the book and a related prophetic passage. An example of this is supplied in the final three chapters of the book.2 By locating the historical narrative of Dan 10 in the early Persian period, it is also possible to propose the same date for the immedi- ately connected and directly related prophecy of Dan 11 - 12.3 Another example of the same kind of relationship can be pro- posed for Dan 9. An historical setting for the prophecy of 924-27 can be inferred indirectly from my previous study on Darius the Mede in Dan 6,4 since the narrative in which this prophecy of 9:24- 27 occurs is dated, in 9:1, to Darius' reign. Thus, this prophecy fits with the indicated early - Persian-period setting, a setting also pre- supposed by the lengthy prayer preceding the prophecy-namely, Daniel's appeal for the fulfillment of Jeremiah's prediction concern- ing the return and restoration of the Judahite exiles (9:4-19). The contents of Daniel's prophecy correlate well in this respect, too, as being a forward look to the future of the community, once it had been restored. -

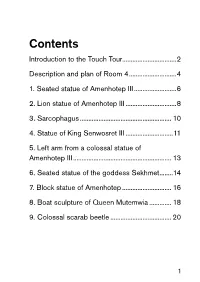

Contents Introduction to the Touch Tour

Contents Introduction to the Touch Tour................................2 Description and plan of Room 4 ............................4 1. Seated statue of Amenhotep III .........................6 2. Lion statue of Amenhotep III ..............................8 3. Sarcophagus ...................................................... 10 4. Statue of King Senwosret III ............................11 5. Left arm from a colossal statue of Amenhotep III .......................................................... 13 6. Seated statue of the goddess Sekhmet ........14 7. Block statue of Amenhotep ............................. 16 8. Boat sculpture of Queen Mutemwia ............. 18 9. Colossal scarab beetle .................................... 20 1 Introduction to the Touch Tour This tour of the Egyptian Sculpture Gallery is a specially designed Touch Tour for visitors with sight difficulties. This guide gives you information about nine highlight objects in Room 4 that you are able to explore by touch. The Touch Tour is also available to download as an audio guide from the Museum’s website: britishmuseum.org/egyptiantouchtour If you require assistance, please ask the staff on the Information Desk in the Great Court to accompany you to the start of the tour. The sculptures are arranged broadly chronologically, and if you follow the tour sequentially, you will work your way gradually from one end of the gallery to the other moving through time. Each sculpture on your tour has a Touch Tour symbol beside it and a number. 2 Some of the sculptures are very large so it may be possible only to feel part of them and/or you may have to move around the sculpture to feel more of it. If you have any questions or problems, do not hesitate to ask a member of staff.