The Dismantling of the Septizonium – a Rational, Utilitarian and Economic Process?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Experience the Greatest Engineering Feat of Renaissance Italy, …

Experience a book that documents the greatest engineering achievement of Renaissance Italy Domenico Fontana, Della Trasportatione dell’Obelisco Vaticano. Rome: D. Basa, 1590. 17 1/8 inches x 11 3/8 inches (435 x 289 mm), 216 pages, including 38 engraved plates. One of the first stops for any visitor to Rome is the oval piazza known as St. Peter’s Square. At the very center, against the imposing backdrop of St. Peter’s Basilica, with its huge façade and its famous dome, an obelisk of pink granite from Egypt perches with surprising lightness on the backs of four miniature bronze lions. It is virtually impossible for us now to imagine the Vatican any other way. In 1585, however, not one piece of this spectacular view had yet been set in place. Carved of Aswan granite in the reign of Nebkaure Amenemhet II (1992– 1985 BC), the obelisk originally stood before the monumental gateway to the Temple of the Sun at Heliopolis. It was brought to Rome in 37 AD by the emperor Caligula as one of many tokens of the Roman conquest of Egypt, and was erected in the Circus of Caligula (later the Circus of Nero). In 1585, Pope Sixtus V announced that he would move the obelisk as part of his master plan for the renovation of the city of Rome. Five hundred contenders thronged to the city to present their plans for the feat, but that of Domenico Fontana seemed to promise the most successful results: Fontana’s huge wooden scaffolding, each leg made of four tree trunks bound together, took the full measure of the granite hulk it was designed to move with gentle precision. -

Short-Term Study Abroad Program Information

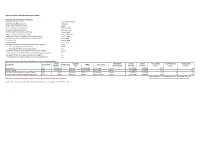

Short-Term Study Abroad Program Information Please provide the following information: Study Abroad Program Name: UGA Classics in Rome Study Abroad (SABD) Course ID: SABD 1107 Study Abroad (SABD) Course CRN: TBD Semester Program will be Offered: Summer 2019 Part of Term (Select Part of Term that most closely aligns with program dates)* : Extended Summer Session Click Here for Part of Term Dates ("Classes Begin" and "Classes End") Program Director/Contact Name: Elena Bianchelli, Chris Gregg Program Director/Contact Phone Number: 706-206-6096, 202-904-3878 Program Director/Contact Email Address: [email protected], [email protected] Program Start Date (First meeting with enrolled students ): 6/2/2019 Program End Date (Last meeting with enrolled students ): 7/11/2019 Travel Start Date: 6/2/2019 Travel End Date: 7/11/2019 Anticipated Number of Total Students Participating in Program: 24 Anticipated Number of UGA Students: 20 Anticipated Number of Transient Students: 4 Anticipated Number of Undergraduate Students in the Program: 20-24 Total Number of Credit Hours Taken by Each Undergraduate Student: 9 Anticipated Number of Graduate Students in the Program: 0-4 Total Number of Credit Hours Taken by Each Graduate Student: 6 Please list each course offered through the program on a separate row below: Schedule Department Course Course Total Lecture Total Field/ Lab Total Contact Course Title Course Prefix Course Number Credit Hours Instructor(s) Type of Instructor(s) Start Date End Date Hours Hours Hours** Ancient Rome CLAS 4350/6350 3 Lecture Chris -

Short-Term Study Abroad Program Information

Short-Term Study Abroad Program Information Please provide the following information: Study Abroad Program Name: UGA Classics in Rome Study Abroad (SABD) Course ID: SABD 1107 Study Abroad (SABD) Course CRN: 54169 Semester Program will be Offered: Summer 2018 Program Director/Contact Name: Elena Bianchelli Program Director/Contact Phone Number: 706 542 8392 Program Director/Contact Email Address: [email protected] Program Start Date (First meeting with enrolled students ): May 27, 2018 Program End Date (Last meeting with enrolled students ): July 5, 2018 Travel Start Date: May 26, 2018 Travel End Date: July 5, 2018 Anticipated Number of Total Students Participating in Program: 15-20 Anticipated Number of UGA Students: 13-17 Anticipated Number of Transient Students: 0-4 Anticipated Number of Undergraduate Students in the Program: 15-20 Total Number of Credit Hours Taken by Each Undergraduate Student: 9 Anticipated Number of Graduate Students in the Program: 0-2 Total Number of Credit Hours Taken by Each Graduate Student: 6 Please list each course offered through the program on a separate row below: Course Schedule Department Course Course Total Lecture Total Field/ Lab Total Contact Course Title Course Prefix Credit Hours CRN(s) Instructor(s) Number Type of Instructor(s) Start Date End Date Hours Hours Hours* Ancient Rome CLAS 4350/6350 3 Lecture 60546/61881 Chris Gregg Classics 5/27/2018 7/5/2018 38.5 7 42 The Art of Rome CLAS 4400/6400 3 Lecture 60547/61882 Chris Gregg Classics 5/27/2018 7/5/2018 37.5 6 40.5 The Urban Tradition of Rome (Selected Topics) CLAS 4305 3 Seminar 60548 Chris Gregg Classics 5/27/2018 7/5/2018 38 6 41 The Latin Tradition of Rome (Advanced Readings) LATN 4405 3 Seminar 61355 Elena Bianchelli Classics 5/27/2018 7/5/2018 37.5 4 39.5 *Total Contact Hours = Total Lecture Hours + (Total Field Hours / 2) Please also complete the Academic Itinerary found on the second worksheet of this document. -

The Courtyard of Honour the Courtyard

The Courtyard of Honour The Courtyard of Honour of the Quirinale Palace appears to be a large arcaded piazza, unified and harmonious in shape, but it is in fact the result of four separate phases of construction which were carried out between the end of the 1500s and next century. The oldest and most easily distinguishable section forms the backdrop to the courtyard with the tower rising above it. This part of the palace was originally an isolated villa, whose construction was begun in 1583 by Pope Gregory XIII who wished to pass the hot Roman summers on the Quirinal Hill, a fresher and airier location than the Vatican. The architect who designed this first building was Ottaviano Mascarino, from Bologna. The next pope, Sixtus V, decided to enlarge the structure with a long wing running down the piazza and a second building directly in front of the older villa; Domenico Fontana was in charge of these projects. The palace and the Courtyard were completed under Pope Paul V by the architect Flaminio Ponzio, who designed the wing on the side of the gardens, and Carlo Maderno, who rebuilt the Sixtus V structure in order that it could accommodate larger and more solemn ceremonial spaces. The clock-tower was originally a simple viewing tower crowning the 16th Century villa. At the beginning of the 17th Century it was fitted with a clock and bell, and towards the end of that century a mosaic of the Madonna and Child was carried out, based on a design by Carlo Maratta. Above the tower fly the Italian and European flags as well as the presidential standard, which is lowered when the Head of State is not in Rome. -

Santa Maria Maggiore St Mary Major

Santa Maria Maggiore St Mary Major Piazza di Santa Maria Maggiore Santa Maria Maggiore is a 5th century papal basilica, located in the rione Monti. and is notable for its extensive Early Christian mosaics. The basilica is built on the summit of the Esquiline hill, which was once a commanding position. (1) (i)! History Ancient times The church is on the ancient Cispius, the main summit of the Esquiline Hill, which in ancient times was not a heavily built-up area. Near the site had been a Roman temple dedicated to a goddess of childbirth, Juno Lucina, much frequented by women in late pregnancy. Archaeological investigations under the basilica between 1966 and 1971 revealed a 1st century building, it seems to have belonged to a villa complex of the Neratii family. (1) (k) Liberian Basilica - Foundation legend - Civil war According to the Liber Pontificalis, this first church (the so-called Basilica Liberiana or "Liberian Basilica") was founded in the August 5, 358 by Pope Liberius. According to the legend that dates from 1288 A.D., the work was financed by a Roman patrician John, and his wife. They were childless, and so had decided to leave their fortune to the Blessed Virgin. She appeared to them in a dream, and to Pope Liberius, and told them to build a church in her honor on a site outlined by a miraculous snowfall, which occurred in August (traditionally in 358). Such a patch of snow was found on the summit of the Esquiline the following morning. The pope traced the outline of the church with his stick in the snow, and so the church was built. -

Architecture and Royal Presence

Architecture and Royal Presence Architecture and Royal Presence: Domenico and Giulio Cesare Fontana in Spanish Naples (1592-1627) By Sabina de Cavi Architecture and Royal Presence: Domenico and Giulio Cesare Fontana in Spanish Naples (1592-1627), by Sabina de Cavi This book first published 2009 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2009 by Sabina de Cavi All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-0180-1, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-0180-5 Per l’amore, che ho ricevuto da mia madre Per la tenacia, che ho appreso da mio padre Per la dolcezza, che vedo in mio fratello Per l’infinito, che esiste in mio marito TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements .................................................................................... ix List of Illustrations ................................................................................... xiii Picture Credits ........................................................................................ xxiv Introduction ............................................................................................... 1 Spanish Naples: Problems, Historiography, and Method CHAPTER I............................................................................................ -

8.5 X12.5 Doublelines.P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-62445-9 - Rome Edited by Marcia B. Hall Frontmatter More information ARTISTIC CENTERS OF THE ITALIAN RENAISSANCE ROME S This volume provides a comprehensive overview of the arts in Rome – ar- chitecture, sculpture, painting, and the decorative arts – within their social, religious, and historical contexts from 1300 to 1600. Organized around the pa- tronage of the popes, it examines the decline of the arts during the period of the Great Schism and the exile of the popes in Avignon, and the revival that began with Pope NicholasV in the middle of the fifteenth century,when Rome began to rebuild itself and reassert its leadership as the center of the Christian world. During the second half of this century,artists and patrons drew inspira- tion from the ruins of antiquity that inhabited the city. By the first decade of the sixteenth century, under the visionary guidance of Pope Julius II and the humanists of the papal court who surrounded him, Rome reestablished itself as the Christian reembodiment of the Roman Empire.The works created by Bramante, Raphael, and Michelangelo, among others, define the High Renais- sance and were to have an enduring influence on the arts throughout Italy and Europe. Despite the challenges posed by the Reformation and the secession of the Protestant churches in the early sixteenth century,the Roman Church and the art establishment transformed themselves. By the last quarter of the century, a new aesthetic inaugurated the Roman baroque and was put into the service of the Counter-Reformation and the Church Triumphant. -

St. Peter's Basilica

Ouachita Baptist University Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita Honors Theses Carl Goodson Honors Program 1969 St. Peter's Basilica Stan Moore Ouachita Baptist University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/honors_theses Part of the Architectural History and Criticism Commons Recommended Citation Moore, Stan, "St. Peter's Basilica" (1969). Honors Theses. 604. https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/honors_theses/604 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Carl Goodson Honors Program at Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ST. FETER ~ S , BASILICA During the swnmers of 196'3 and 1969 I traveled in Europe touring 11 countries by bus in 68 and a major cities tour in 69 . On the tours I took films with a Bolex super 8 movie camera and also bought corrunercial slides. Hy interest in Art , Sculpture , Architecture and History was inhanced by this opportunity in visiting the many mueseums , cathedrals and birth cities that contain within themselves the p1·oeressions of the art eras •. Outstanding, of course, in places visited ; was Italy. In medival times Italy was a more fertile grounq for general economic an~ political conditions to develop. This enhance~ an individualism. An inquisitiveness about their past trigeered the study of antiquity. The study of the science and philosophies of their past added a realism and humanism developing class,ic art and culture. The inquisitiveness of antiquity adds the realism, individualism and humanism which makes Italy the cradle of the Renaissance movement . -

![Ticinese Architects and Sculptors in Past Centuries [Continued]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9612/ticinese-architects-and-sculptors-in-past-centuries-continued-6119612.webp)

Ticinese Architects and Sculptors in Past Centuries [Continued]

Ticinese architects and sculptors in past centuries [continued] Autor(en): Tanner, A. Objekttyp: Article Zeitschrift: The Swiss observer : the journal of the Federation of Swiss Societies in the UK Band (Jahr): - (1962) Heft 1410 PDF erstellt am: 25.09.2021 Persistenter Link: http://doi.org/10.5169/seals-691184 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch -

Aqueducts for the Urbis Clarissimus Locus: the Palatine’S Water Supply from Republican to Imperial Times

AQUEDUCTS FOR THE URBIS CLARISSIMUS LOCUS: THE PALATINE’S WATER SUPPLY FROM REPUBLICAN TO IMPERIAL TIMES Dr. Andrea Schmölder-Veit, University of Augsburg [email protected] The Palatine hill, where Rome began, was already an to the Palatine’s water supply occurred under Nero, who important center of power long before Imperial palaces built the first unified palace building (not a collection of were built there. As early as the Republican period, elite several independent domus as Augustus had done).7 For residents had constructed monumental architecture on this this he needed more water; therefore, he sponsored a hill above the Roman Forum that publicly advertised their completely new branch that extended the Arcus Neroniani claims to leadership. Also at this time, the greatness of the (Arcus Caelimontani) on the Caelian to the Palatine. This res publica was demonstrated through monumental higher-level line could deliver water to every level of the building projects, which correlated with the gloria of hill, even to nymphaea in the highest courts and gardens. families who dedicated temples in Rome's honor.1 As nothing is known about the domus of this period, it can The first conduit for the Palatine in Republican times only be assumed that the Palatine was a residential area The Marcia was the only aqueduct to supply the Palatine populated by elite Romans in the fourth and third century hill during the Republican period. The Aqua Appia (312 BC. For example, Livy (8: 19. 4) tells us that Vitruvius BC) arrived at only about 15 masl (meters above sea level) Vaccus, a very rich Fundanian, had a property on the in the city.8 This was too low, even for the houses at the Palatine before 330 BC. -

Palazzi of the Republic

ALAZZI OF THE PRome’s Major Government EPUBLIC Buildings R AZIENDA DI PROMOZIONE TURISTICA DI ROMA The Quirinale Palace is the seat of the President of the Republic, the highest institution of the Italian state and therefore the "House of all Italians", the point of reference for all citizens in developing an affinity with public institutions. I am firmly convinced that the attitude towards public institutions is central to the history of society and the history of a people. The values of civilised society reside in our consciences, and come alive only in a context of real human relationships and of belief in public institutions and their importance. We create public institutions to organise our civil life and to ensure that the fundamental principles common to everyone's conscience are coupled with an awareness of the rules of living together, and therefore of the institutions which regulate the life of a community. Carlo Azeglio Ciampi President of the Italian Republic PALAZZI OF THE REPUBLIC CONTENTS Quirinale Palace pag. 3 Presidency of the Republic Palazzo Madama ” 9 Senate of the Republic Palazzo Montecitorio ” 15 Chamber of Deputies Palazzo della Consulta ” 21 Constitutional Court Palazzo Chigi ” 27 Presidency of the Council of Ministers (Prime Minister) THE QUIRINALE PALACE Presidency of the Republic THE SITE IN ANTIQUITY renowned as the biggest temple The Quirinale Palace stands on one complex in the city; and the baths of the peaks of the hill of the same of Constantine, built around name, the highest and largest of the year 315 on the nor- Rome’s seven hills. -

I from Treasure Hunting to Archaeological Dig. History of the Excavations of Herculaneum and Pompeii

I From Treasure Hunting to Archaeological Dig. History of the Excavations of Herculaneum and Pompeii In Antiquity, the region at the foot of Vesuvius was renowned for its healthy climate, fertility and beauty. There were good ports in ancient Herculaneum and Pompeii, and navigable rivers flanked Pompeii. The area was rather densely inhabited by people living in farmsteads, villages and small cities. Pompeii, Herculaneum and Stabiae, lying around Vesuvius, were to be singled out in history because of their unhappy fortune in A.D. 79, not thanks to specific features that placed the towns above other average settlements in the Roman world. Undoubtedly, many eruptions had happened before – some of them are also known from stratigraphic excavations – but Vesuvius seemed dead, or had been sleeping for ages, when it exploded in 79.3 This eruption was so powerful that the fill of the wide caldara – which looked like a plain top next to the ridge of Monte Somma – was blown up, crumbled by the heat and the gases coming from inside the earth. Thanks to a long description of the event in two letters by the younger Pliny, seventeen years old at the time, written some twenty years later to his friend, the historian Tacitus, volcanologists are able to reconstruct the event. Many people were able to save themselves, but a great number died on this day of hell.4 The small towns had no particular importance within the Roman Empire. They are barely mentioned in the written sources we possess,5 and many questions remain open: when were they founded and who were their first inhabitants? How did they develop? Herculaneum was said to have been founded by Hercules; the other places do not have a foundation myth, but the same Hercules would also be the founder of Pompeii.