The Maturing of the Computer Game." Electronic Dreams: How 1980S Britain Learned to Love the Computer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Xbox 360 Total Size (GB) 0 # of Items 0

Done In this Category Xbox 360 Total Size (GB) 0 # of items 0 "X" Title Date Added 0 Day Attack on Earth July--2012 0-D Beat Drop July--2012 1942 Joint Strike July--2012 3 on 3 NHL Arcade July--2012 3D Ultra Mini Golf July--2012 3D Ultra Mini Golf Adventures 2 July--2012 50 Cent: Blood on the Sand July--2012 A World of Keflings July--2012 Ace Combat 6: Fires of Liberation July--2012 Ace Combat: Assault Horizon July--2012 Aces of Galaxy Aug--2012 Adidas miCoach (2 Discs) Aug--2012 Adrenaline Misfits Aug--2012 Aegis Wings Aug--2012 Afro Samurai July--2012 After Burner: Climax Aug--2012 Age of Booty Aug--2012 Air Conflicts: Pacific Carriers Oct--2012 Air Conflicts: Secret Wars Dec--2012 Akai Katana July--2012 Alan Wake July--2012 Alan Wake's American Nightmare Aug--2012 Alice Madness Returns July--2012 Alien Breed 1: Evolution Aug--2012 Alien Breed 2: Assault Aug--2012 Alien Breed 3: Descent Aug--2012 Alien Hominid Sept--2012 Alien vs. Predator Aug--2012 Aliens: Colonial Marines Feb--2013 All Zombies Must Die Sept--2012 Alone in the Dark Aug--2012 Alpha Protocol July--2012 Altered Beast Sept--2012 Alvin and the Chipmunks: Chipwrecked July--2012 America's Army: True Soldiers Aug--2012 Amped 3 Oct--2012 Amy Sept--2012 Anarchy Reigns July--2012 Ancients of Ooga Sept--2012 Angry Birds Trilogy Sept--2012 Anomaly Warzone Earth Oct--2012 Apache: Air Assault July--2012 Apples to Apples Oct--2012 Aqua Oct--2012 Arcana Heart 3 July--2012 Arcania Gothica July--2012 Are You Smarter that a 5th Grader July--2012 Arkadian Warriors Oct--2012 Arkanoid Live -

Links to the Past User Research Rage 2

ALL FORMATS LIFTING THE LID ON VIDEO GAMES User Research Links to Game design’s the past best-kept secret? The art of making great Zelda-likes Issue 9 £3 wfmag.cc 09 Rage 2 72000 Playtesting the 16 neon apocalypse 7263 97 Sea Change Rhianna Pratchett rewrites the adventure game in Lost Words Subscribe today 12 weeks for £12* Visit: wfmag.cc/12weeks to order UK Price. 6 issue introductory offer The future of games: subscription-based? ow many subscription services are you upfront, would be devastating for video games. Triple-A shelling out for each month? Spotify and titles still dominate the market in terms of raw sales and Apple Music provide the tunes while we player numbers, so while the largest publishers may H work; perhaps a bit of TV drama on the prosper in a Spotify world, all your favourite indie and lunch break via Now TV or ITV Player; then back home mid-tier developers would no doubt ounder. to watch a movie in the evening, courtesy of etix, MIKE ROSE Put it this way: if Spotify is currently paying artists 1 Amazon Video, Hulu… per 20,000 listens, what sort of terrible deal are game Mike Rose is the The way we consume entertainment has shifted developers working from their bedroom going to get? founder of No More dramatically in the last several years, and it’s becoming Robots, the publishing And before you think to yourself, “This would never increasingly the case that the average person doesn’t label behind titles happen – it already is. -

![[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3367/japan-sala-giochi-arcade-1000-miglia-393367.webp)

[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia

SCHEDA NEW PLATINUM PI4 EDITION La seguente lista elenca la maggior parte dei titoli emulati dalla scheda NEW PLATINUM Pi4 (20.000). - I giochi per computer (Amiga, Commodore, Pc, etc) richiedono una tastiera per computer e talvolta un mouse USB da collegare alla console (in quanto tali sistemi funzionavano con mouse e tastiera). - I giochi che richiedono spinner (es. Arkanoid), volanti (giochi di corse), pistole (es. Duck Hunt) potrebbero non essere controllabili con joystick, ma richiedono periferiche ad hoc, al momento non configurabili. - I giochi che richiedono controller analogici (Playstation, Nintendo 64, etc etc) potrebbero non essere controllabili con plance a levetta singola, ma richiedono, appunto, un joypad con analogici (venduto separatamente). - Questo elenco è relativo alla scheda NEW PLATINUM EDITION basata su Raspberry Pi4. - Gli emulatori di sistemi 3D (Playstation, Nintendo64, Dreamcast) e PC (Amiga, Commodore) sono presenti SOLO nella NEW PLATINUM Pi4 e non sulle versioni Pi3 Plus e Gold. - Gli emulatori Atomiswave, Sega Naomi (Virtua Tennis, Virtua Striker, etc.) sono presenti SOLO nelle schede Pi4. - La versione PLUS Pi3B+ emula solo 550 titoli ARCADE, generati casualmente al momento dell'acquisto e non modificabile. Ultimo aggiornamento 2 Settembre 2020 NOME GIOCO EMULATORE 005 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1 On 1 Government [Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 10-Yard Fight SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 18 Holes Pro Golf SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1941: Counter Attack SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1942 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943: The Battle of Midway [Europe] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1944 : The Loop Master [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1945k III SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 19XX : The War Against Destiny [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 4-D Warriors SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 64th. -

The Many Lives of the Jetman: a Case Study in Video Game Analysis Will Brooker

The Many Lives of the Jetman: A Case Study in Video Game Analysis Will Brooker This article examines the changing meanings and forms of the computer game Jetpac, which was originally released by Ultimate for the ZX Spectrum in 1983 and has been recoded by individual programmers during the late 1990s, in at least three different shareware versions, for PC and Spectrum emulators. Through this analysis, it asks a simple question: how can we approach, and perhaps teach, the academic study of computer and video games? Introduction: Games and Theory At the present time, it seems that the study of video games is considered suitable for courses in technical production and for magazine and newspaper reviews, but not for academic degree modules or, with very few exceptions, for scholarly analysis [1]. Video games are a job for those at the design and coding end of the process, and a leisure pursuit for those at the consumption end. There exists very little critical framework for analysing this unique media form. This article suggests a possible set of approaches, based partially on the two pioneering studies of video games of the late 1990s: J.C. Herz’s Joystick Nation (London, Abacus 1997) and Steven Poole’s Trigger Happy (London: Fourth Estate, 2000). Both are exceptional and invaluable sallies into the field, yet both tend towards the journalistic, crafting nifty prose and snappy rhetoric at the expense of academic conventions. Poole, for instance, ends his early chapter sub-sections with slogan-neat but essentially meaningless tags such as “Kill them all”, [2] “You were just too slow” [3] “Go ahead, jump”[4] and, perhaps most glaringly, “The fighting game, like fighting itself, will always be popular”[5]. -

Aboard the Impulse Train: an Analysis of the Two- Channel Title Music Routine in Manic Miner Kenneth B

All aboard the impulse train: an analysis of the two- channel title music routine in Manic Miner Kenneth B. McAlpine This is the author's accepted manuscript. The final publication is available at Springer via http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s40869-015-0012-x All Aboard the Impulse Train: An analysis of the two-channel title music routine in Manic Miner Dr Kenneth B. McAlpine University of Abertay Dundee Abstract The ZX Spectrum launched in the UK in April 1982, and almost single- handedly kick-started the British computer games industry. Launched to compete with technologically-superior rivals from Acorn and Commodore, the Spectrum had price and popularity on its side and became a runaway success. One area, however, where the Spectrum betrayed its price-point was its sound hardware, providing just a single channel of 1-bit sound playback, and the first-generation of Spectrum titles did little to challenge the machine’s hardware. Programmers soon realised, however, that with clever machine coding, the Spectrum’s speaker could be encouraged to do more than it was ever designed to. This creativity, borne from constraint, represents a very real example of technology, or rather limited technology, as a driver for creativity, and, since the solutions were not without cost, they imparted a characteristic sound that, in turn, came to define the aesthetic of ZX Spectrum music. At the time, there was little interest in the formal study of either the technologies that support computer games or the social and cultural phenomena that surround them. This retrospective study aims to address that by deconstructing and analysing a key turning point in the musical life of the ZX Spectrum. -

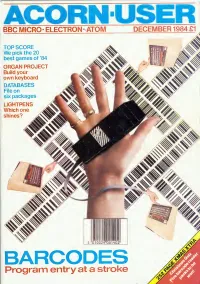

Acorn User Welcomes Submissions Irom Readers

ACORN BBC MICRO- ELECTRON- ATOM DECEMBER 1984 £1 TOP SCORE We pick the 20 best games of '84 ORGAN PROJECT Build your own keyboard DATABASES File on six packages LIGHTPENS Which one shines? Program entry at a stroke ' MUSIC MICRO PLEASE!! Jj V L S ECHO I is a high quality 3 octave keyboard of 37 full sized keys operating electroni- cally through gold plated contacts. The keyboard which is directly connected to the user port of the computer does not require an independent power supply unit. The ECHOSOFT Programme "Organ Master" written for either the BBC Model B' or the Commodore 64 supplied with the keyboard allows these computers to be used as real time synth- esizers with full control of the sound envelopes. The pitch and duration of the sound envelope can be changed whilst playing, and the programme allows the user to create and allocate his own sounds to four pre-defined keys. Additional programmes in the ECHOSOFT Series are in the course of preparation and will be released shortly. Other products in the range available from your LVL Dealer are our: ECHOKIT (£4.95)" External Speaker Adaptor Kit, allows your Commodore or BBC Micro- computer to have an external sound output socket allowing the ECHOSOUND Speaker amplifier to be connected. (£49.95)' - ECHOSOUND A high quality speaker amplifier with a 6 dual cone speaker and a full 6 watt output will fill your room with sound. The sound frequency control allows the tone of the sound output to be changed. Both of the above have been specifically designed to operate with the ECHO Series keyboard. -

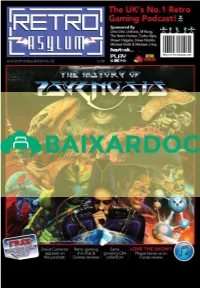

Retro Asylum Asked If I Would Help Do Some Research for Their Upcoming Psygnosis Podcast, It Was a Task of Which I Was Honoured to Do

The stunning Front cover art has been put together by Phil Hockaday. A truly memorising piece of art that encapsulates all that was great about Psygnosis. Thank you Phil for your stunning talent and efforts. 2014 Introduction When Sam (MrSid) and Steve (PressPlayonTape) from Retro Asylum asked if I would help do some research for their upcoming Psygnosis podcast, it was a task of which I was honoured to do. The trouble is though, I don’t like doing things by half, and so as I started to compile some research notes, and the pages started to mount, I hit upon an idea. If I put the research notes in a nice pretty form, then it could be offered as a free book with the podcast itself. Something that could act as an adjoining love letter to Psygnosis, going right from the beginning of Imagine Software, until it’s final demise under the name SCE Studio Liverpool in 2012. This book covers that story of Psygnosis, followed by a massive game list (a Psygnopaedia ) covering every game Psygnosis has released (hopefully I haven’t missed any). Finally there is a cover gallery section, showing some of the best game box art Psygnosis has produced. Anyway, I hope you enjoy, and hope to see you on the Retro Asylum forum. - Paul Driscoll (AKA The Drisk) Who are we anyway? Retro Asylum http://retroasylum.com/ The UK’s No 1. Retro Gaming Podcast. Or to put it another way, just a group of people passionate about our Retro Gaming, and wanting to make a community of likeminded people. -

AMP17 Acornsoft Order Form Autumn 1984

Autumn 1984 Acornsoft Order form Acornsoft software for the BBC Microcomputer. The symbols tell you in what form the programs areavailable. cassette disc dual format 40/80 track disc ROM indicates suitability for Model A or B indicates you can use joysticks requires 6502 Second Processor. Home Education Spooky Manor SBE18 8.65 9.95 ElSNE18 10.00 11.50 ABC* SBE24 8.65 9.95 SNE24 10.00 11.50 Talkback* SBE22 8.65 9.95 SNE22 10.00 11.50 Workshop* SBE23 8.65 9.95 SNE23 10.00 11.50 Tree of Knowledge SBE04 8.65 9.95 ElSNE04 10.00 11.50 Peeko-Computer SBE02 8.65 9.95 SNE02 10.00 11.50 Business Games SBE03 8.65 9.95 SNE03 10.00 11.50 Podd XBE26 8.65 9.95 XNE26 10.00 11.50 Juggle Puzzle XBE27 8.65 9.95 XNE27 10.00 11.50 Squeeze XBE28 8.65 9.95 XNE28 10.00 11.50 Facemaker XBE10 8.65 9.95 ElXNE10 10.00 11.50 Words Words Words XBE19 8.65 9.95 El XNE19 10.00 11.50 Hide &Seek XBE11 8.65 9.95 XNE11 10.00 11.50 Total Acornsoft software for the BBC Microcomputer Order form Children from Space XBE16 8.65 9.95 XNE16 10.00 11.50 Let's Count XBE12 8.65 9.95 XNE12 10.00 11.50 Number Gulper XBE13 8.65 9.95 XNE13 . 10.00 11.50 Number Puzzler XBE14 8.65 9.95 XNE14 10.00 11.50 Number Chaser XBE15 8.65 9.95 Et XNE15 10.00 11.50 Cranky XBE17 8.65 9.95 XNE17 10.00 11.50 Table Adventures XBE18 8.65 9.95 XNE18 10.00 11 50 Languages FORTH SBL01 14.65 16.85 SNL01 17.30 19.90 SBL13* 43.35 49.85 LISP SBL02 14.65 16.85 SNL02 17.30 19.90 SBL14 43.35 49.85 LISP Demonstrations SBL09 8.65 9.95 SNL09 10.00 11.50 Microtext SBL04 43.35 49.85 SNL04 52.00 -

Lemmings Game Download Safe

Lemmings game download safe Continue Play a classic puzzle game on your computer with DHTML Lemmings.DHTML Lemmings is a free Windows PC app from Elizium-Drak Rock Music that lets you play the classic Lemmings game.The goal of the game is to get all the lemmings out of the exit at the bottom of the game window. Lemmings will fall out of the hatch above and then you have to guide them using the skills of each lemming. The skill icons are located under the screen and just click on the icon and then particular Lemming activate this skill on it. At each level you will be presented with new puzzles to challenge you and figure out how to get Lemmings to safety. There are 4 all over levels such as fun, tricky, taxing and Mayhem that will be available to you. Download DHTML Lemmings now and enjoy a challenging puzzle game. You can visit Tom's Guide for more information about Windows and Windows Applications.Also check out the forums for Windows. Download Page 2 Play a classic puzzle game on your computer with DHTML Lemmings.DHTML Lemmings is a free Windows PC app from Elizium-Drak Rock Music that lets you play the classic Lemmings game.The goal of the game is to get all the lemmings out of the exit at the bottom of the game window. Lemmings will fall out of the hatch above and then you have to guide them using the skills of each lemming. The skill icons are located under the screen and just click on the icon and then particular Lemming activate this skill on it. -

Index | Table of Contents

Intro: Infinity (175) Before you read this book (3) Jet Force Gemini (176) Copyright, Fair Use & Good Faith (4) Knights (177) Forewords (5) Mythri (178) Unseen Covers 1 (12) Resident Evil (179) The History of Unseen64 (13) Saffire (180) Anonymous sources and research (21) Tyrannosaurus Tex (181) Gaming Philology (23) SNES, MegaDrive (Genesis) Games You Will Never Play (183) Preservation of Cancelled Games (25) Akira (185) Frequently Asked Questions (27) Albert Odyssey Gaiden (186) Games you will (never?) play (29) Christopher Columbus (187) Unseen Covers 2 (32) Dream: Land of Giants (187) Interviews: Felicia (190) Adam McCarthy (33) Fireteam Rogue (190) Art Min (36) Interplanetary Lizards (192) Brian Mitsoda (39) Iron Hammer (193) Centre for Computing History (43) Kid Kirby (194) Computer Spiele Museum (46) Matrix Runner (194) Felix Kupis (49) Mission Impossible (195) Frederic Villain (51) Rayman (196) Gabe Cinquepalmi (54) River Raid (198) Grant Gosler (57) Satellite Man (198) Jesse Sosa (61) Socks the Cat Rocks the Hill (199) John Andersen (64) Spinny and Spike (202) Ken Capelli (69) Starfox 2 (202) NOVAK (75) Super quick (205) MoRE Museum (84) X-Women (207) National Videogame Museum (87) Sega 32X / Mega CD Games You Will Never Play (209) Tim Williams (90) Castlevania: The Bloodletting (210) Omar Cornut (93) Hammer vs. Evil D. in Soulfire (210) Terry Greer (97) Shadow of Atlantis (215) William (Bill) Anderson (101) Sonic Mars (216) Scott Rogers (106) Virtua Hamster (218) PC Games You Will Never Play (111) Philips CDI Games You Will Never -

Nintendo Famicom Indiana Jones

RG16 Cover UK.qxd:RG16 Cover UK.qxd 20/9/06 13:06 Page 1 retro gamer COMMODORE • SEGA • NINTENDO • ATARI • SINCLAIR • ARCADE * VOLUME TWO ISSUE FOUR Nintendo Famicom Is this the best console of all time? Indiana Jones Opening the gaming ark Rare’s GoldenEye 007 heaven on the N64 Pong Wars A brief history of videogames Retro Gamer 16 £5.99 UK $14.95 AUS V2 $27.70 NZ 04 Untitled-1 1 1/9/06 12:55:47 RG16 Intro/Contents.qxd:RG16 Intro/Contents.qxd 20/9/06 14:27 Page 3 <EDITORIAL> Editor = Martyn Carroll ([email protected]) Deputy Editor = Aaron Birch ([email protected]) Art Editor = Craig Chubb Sub Editors = Rachel White + James Clark Contributors = Alicia Ashby + Simon Brew Richard Burton + Jonti Davies Ashley Day + Paul Drury Frank Gasking + Geson Hatchett Craig Lewis + Robert Mellor Per Arne Sandvik + Spanner Spencer John Szczepaniak+Chris Wild <PUBLISHING & ADVERTISING> Operations Manager = Glen Urquhart Group Sales Manager = Linda Henry Advertising Sales = Danny Bowler Accounts Manager = Karen Battrick repare for invasion, should be commended leading up to the event. CGE 2005 Circulation Manager = as retro fans, (knighted?) for his efforts in is on course to surpass last year’s Steve Hobbs helloexhibitors and getting the show on the road. successful debut in every way, Marketing Manager = Iain "Chopper" Anderson celebrities descend The failure of Game Zone Live and it’s hoped that one day the Editorial Director = P on London for the goes to show that even a large show will be as big as its US Wayne Williams second Classic Gaming Expo. -

The Inform Designer's Manual

Cited Works of Interactive Fiction The following bibliography includes only those works cited in the text of this book: it makes no claim to completeness or even balance. An index entry is followed by designer's name, publisher or organisation (if any) and date of first substantial version. The following denote formats: ZM for Z-Machine, L9 for Level 9's A-code, AGT for the Adventure Game Toolkit run-time, TADS for TADS run-time and SA for Scott Adams's format. Games in each of these formats can be played on most modern computers. Scott Adams, ``Quill''-written and Cambridge University games can all be mechanically translated to Inform and then recompiled as ZM. The symbol marks that the game can be downloaded from ftp.gmd.de, though for early games} sometimes only in source code format. Sa1 and Sa2 indicate that a playable demonstration can be found on Infocom's first or second sampler game, each of which is . Most Infocom games are widely available in remarkably inexpensive packages} marketed by Activision. The `Zork' trilogy has often been freely downloadable from Activision web sites to promote the ``Infocom'' brand, as has `Zork: The Undiscovered Underground'. `Abenteuer', 264. German translation of `Advent' by Toni Arnold (1998). ZM } `Acheton', 3, 113 ex8, 348, 353, 399. David Seal, Jonathan Thackray with Jonathan Partington, Cambridge University and later Acornsoft, Topologika (1978--9). `Advent', 2, 47, 48, 62, 75, 86, 95, 99, 102, 105, 113 ex8, 114, 121, 124, 126, 142, 146, 147, 151, 159, 159, 179, 220, 221, 243, 264, 312 ex125, 344, 370, 377, 385, 386, 390, 393, 394, 396, 398, 403, 404, 509 an125.