Cultural Rights and Public Spaces in Iraq

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 UCL INSTITUTE of ARCHAEOLOGY ARCL0199: Heritage Ethics and Archaeological Practice in the Middle East and Mediterranean 2019

UCL INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY ARCL0199: Heritage Ethics and Archaeological Practice in the Middle East and Mediterranean 2019–20 MA Module (15 credits) Turnitin Class ID: 3885721 Turnitin Password IoA1819 Deadlines for coursework for this module: Essay 1: Monday 17th February (returned by 2 March) Essay 2: Friday 3 April (returned by 1 May) Co-ordinator: Corisande Fenwick/ Alice Stevenson Email: [email protected] / [email protected] Tel: 0207-679-4746 Room 502 Office hours: Corisande Fenwick (Fri 11:30am—1:30pm) Alice Stevenson (Wed 10am-12pm). Please see the last page of this document for important information about submission and marking procedures, or links to the relevant webpages. 1 1. OVERVIEW This module provides a comparative overview of key debates, as well as the frameworks of practice, policy and ethical issues in cultural heritage as they are played out in the Middle East and Mediterranean today. Key themes include the history of archaeology in the region, museum practice, archaeology in conflict zones, disaster recovery, illicit trade in antiquities, UNESCO politics, legislation, fieldwork ethics, site management, stakeholders and audience. Throughout the emphasis is on comparative, critical analysis of contemporary practices in heritage, grounded in real-world case-studies from the region. Week-by-week summary (SG = Seminar Group) Date Topic 2-3pm 3-4pm 4-5pm 1 16 Jan Introduction: Archaeology and the Lecture Scramble for the Past 2 23 Jan Who owns the past? From national to Lecture SG 1 SG 2 universal heritage. -

18 January, 2018 FUNDED by THE

REPORT ON THE FRIENDS OF BASRAH MUSEUM Training Programme Basrah Museum, 13 – 18 January, 2018 by Joan Porter MacIver FOBM UK Project Co‐ordinator Training Partnership with The Ashmolean Museum, The Aga Khan Museum, GlasgowLife Glasgow Museums and The British Institute for the Study of Iraq FUNDED BY THE CULTURAL PROTECTION FUND Managed by the British Council in partnership with DCMS. Participants in the FOBM Training Programme on 18 January 2018 Back row [Left to Right]– Sarmad Saleem (Basrah Museum), Fadhil Abdel Abbas (Basrah Museum), Dr Noorah Al‐Gailani (Trainer & Glasgow Museums), Haitham Muhsen Sfoog (Baghdad – previously Basrah) and Magid Kassim Kadhim (Basrah Museum); Middle Row – Dr Lamia al Gailani‐Werr (FOBM Trustee), Siham Giwad Kadhun (Director Maisan Museum), Dr Ulrike Al‐Khamis (Trainer & Aga Khan Museum), Iqbal Kadhim Ajeel (Director Nasiriya Museum), Sufian Muhsen (Governates’ Museum Department, SBAH/Iraq Museum), Dr Paul Collins (Trainer & Ashmolean Museum), Dr Adil Kassim Sassim (Head of the Natural History Museum, Basrah, & University of Basrah), Wissam Abd Ali Abdul Hussain (Basrah Museum), Salwan Adnan Alahmar (Samawa Museum), Tamara Alattiyeh (Museum Volunteer and Saraji Palace Museum Project coordinator designate), Sakna Jaber Abdel Latif (Museum Volunteer), Ayat Fadhil Sadkan (Museum Volunteer) and Ali Khadr (Evaluation Report & BISI); Front row kneeling: Joan Porter MacIver (FOBM & BISI), Abdel Razak Khadim (Basrah Museum), Qahtan Al Abeed (Basrah Museum Director) and, Salah Rahi (Samawa Museum) Missing from -

Cultural Orientation | Kurmanji

KURMANJI A Kurdish village, Palangan, Kurdistan Flickr / Ninara DLIFLC DEFENSE LANGUAGE INSTITUTE FOREIGN LANGUAGE CENTER 2018 CULTURAL ORIENTATION | KURMANJI TABLE OF CONTENTS Profile Introduction ................................................................................................................... 5 Government .................................................................................................................. 6 Iraqi Kurdistan ......................................................................................................7 Iran .........................................................................................................................8 Syria .......................................................................................................................8 Turkey ....................................................................................................................9 Geography ................................................................................................................... 9 Bodies of Water ...........................................................................................................10 Lake Van .............................................................................................................10 Climate ..........................................................................................................................11 History ...........................................................................................................................11 -

31 DECEMBER 2011 Programme Title &Am

IRAQ TRUST FUND ANNUAL PROGRAMME1 NARRATIVE PROGRESS REPORT REPORTING PERIOD: 1 JANUARY – 31 DECEMBER 2011 Programme Title & Number Country, Locality(s), Thematic Area(s)2 Programme Title: Modernizing Sulaymaniyah Country: Iraq, Museum, pilot for Museum Sector in Iraq Governorate: Sulaymaniyah Town: Sulaymaniyah Programme Number: Project B1-37 Sector: Education MDTF Office Atlas Number: Participating Organization(s) Implementing Partners UNESCO KRG Prime Minister Office KRG Ministry of Municipalities and Tourism KRG Ministry of Education Programme/Project Cost (US$) Programme Duration (months) Overall Duration: UNDG ITF: USD 350,000 12 months 3 Agency Core: UNESCO USD 50,000 Start Date : 1/7/2010 End Date or Govt. Contribution: Revised End Date, 23/8/2012 Other Contribution (donor) Operational Closure Date4 TOTAL: USD 400,000 Programme Assessments/Mid-Term Evaluation Submitted By Assessment Completed - if applicable please o Name: Geraldine Chatelard attach o Title: Programme Specialist Yes No Date: __________________ o Participating Organization (Lead): 1 The term “programme” is used for programmes, joint programmes and projects. 2 Priority Area for the Peacebuilding Fund; Sector for the UNDG ITF. 3 The start date is the date of the first transfer of the funds from the MDTF Office as Administrative Agent. Transfer date is available on the MDTF Office GATEWAY (http://mdtf.undp.org). 4 All activities for which a Participating Organization is responsible under an approved MDTF programme have been completed. Agencies to advise the MDTF Office. Page 1 of 13 Mid-Evaluation Report – if applicable please UNESCO attach o Email address: [email protected] Yes No Date: __________________ Introduction: The Suleimanyah Museum is an ideal flagship candidate for introducing state-of-the-art museology and internationally recognized good-practices in the Kurdistan region. -

The Politics of Security in Ninewa: Preventing an ISIS Resurgence in Northern Iraq

The Politics of Security in Ninewa: Preventing an ISIS Resurgence in Northern Iraq Julie Ahn—Maeve Campbell—Pete Knoetgen Client: Office of Iraq Affairs, U.S. Department of State Harvard Kennedy School Faculty Advisor: Meghan O’Sullivan Policy Analysis Exercise Seminar Leader: Matthew Bunn May 7, 2018 This Policy Analysis Exercise reflects the views of the authors and should not be viewed as representing the views of the US Government, nor those of Harvard University or any of its faculty. Acknowledgements We would like to express our gratitude to the many people who helped us throughout the development, research, and drafting of this report. Our field work in Iraq would not have been possible without the help of Sherzad Khidhir. His willingness to connect us with in-country stakeholders significantly contributed to the breadth of our interviews. Those interviews were made possible by our fantastic translators, Lezan, Ehsan, and Younis, who ensured that we could capture critical information and the nuance of discussions. We also greatly appreciated the willingness of U.S. State Department officials, the soldiers of Operation Inherent Resolve, and our many other interview participants to provide us with their time and insights. Thanks to their assistance, we were able to gain a better grasp of this immensely complex topic. Throughout our research, we benefitted from consultations with numerous Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) faculty, as well as with individuals from the larger Harvard community. We would especially like to thank Harvard Business School Professor Kristin Fabbe and Razzaq al-Saiedi from the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative who both provided critical support to our project. -

Ba'ath Propaganda During the Iran-Iraq War Jennie Matuschak [email protected]

Bucknell University Bucknell Digital Commons Honors Theses Student Theses Spring 2019 Nationalism and Multi-Dimensional Identities: Ba'ath Propaganda During the Iran-Iraq War Jennie Matuschak [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses Part of the International Relations Commons, and the Near and Middle Eastern Studies Commons Recommended Citation Matuschak, Jennie, "Nationalism and Multi-Dimensional Identities: Ba'ath Propaganda During the Iran-Iraq War" (2019). Honors Theses. 486. https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses/486 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses at Bucknell Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Bucknell Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. iii Acknowledgments My first thanks is to my advisor, Mehmet Döşemeci. Without taking your class my freshman year, I probably would not have become a history major, which has changed my outlook on the world. Time will tell whether this is good or bad, but for now I am appreciative of your guidance. Also, thank you to my second advisor, Beeta Baghoolizadeh, who dealt with draft after draft and provided my thesis with the critiques it needed to stand strongly on its own. Thank you to my friends for your support and loyalty over the past four years, which have pushed me to become the best version of myself. Most importantly, I value the distractions when I needed a break from hanging out with Saddam. Special shout-out to Andrew Raisner for painstakingly reading and editing everything I’ve written, starting from my proposal all the way to the final piece. -

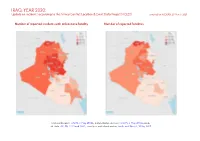

IRAQ, YEAR 2020: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 25 March 2021

IRAQ, YEAR 2020: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 25 March 2021 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, 6 May 2018b; administrative divisions: GADM, 6 May 2018a; incid- ent data: ACLED, 12 March 2021; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 IRAQ, YEAR 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 MARCH 2021 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Protests 1795 13 36 Conflict incidents by category 2 Explosions / Remote 1761 308 824 Development of conflict incidents from 2016 to 2020 2 violence Battles 869 502 1461 Methodology 3 Strategic developments 580 7 11 Conflict incidents per province 4 Riots 441 40 68 Violence against civilians 408 239 315 Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 5854 1109 2715 Disclaimer 7 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 12 March 2021). Development of conflict incidents from 2016 to 2020 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 12 March 2021). 2 IRAQ, YEAR 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 MARCH 2021 Methodology on what level of detail is reported. Thus, towns may represent the wider region in which an incident occured, or the provincial capital may be used if only the province The data used in this report was collected by the Armed Conflict Location & Event is known. -

Kurdistan Rising? Considerations for Kurds, Their Neighbors, and the Region

KURDISTAN RISING? CONSIDERATIONS FOR KURDS, THEIR NEIGHBORS, AND THE REGION Michael Rubin AMERICAN ENTERPRISE INSTITUTE Kurdistan Rising? Considerations for Kurds, Their Neighbors, and the Region Michael Rubin June 2016 American Enterprise Institute © 2016 by the American Enterprise Institute. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be used or reproduced in any man- ner whatsoever without permission in writing from the American Enterprise Institute except in the case of brief quotations embodied in news articles, critical articles, or reviews. The views expressed in the publications of the American Enterprise Institute are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the staff, advisory panels, officers, or trustees of AEI. American Enterprise Institute 1150 17th St. NW Washington, DC 20036 www.aei.org. Cover image: Grand Millennium Sualimani Hotel in Sulaymaniyah, Kurdistan, by Diyar Muhammed, Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons. Contents Executive Summary 1 1. Who Are the Kurds? 5 2. Is This Kurdistan’s Moment? 19 3. What Do the Kurds Want? 27 4. What Form of Government Will Kurdistan Embrace? 56 5. Would Kurdistan Have a Viable Economy? 64 6. Would Kurdistan Be a State of Law? 91 7. What Services Would Kurdistan Provide Its Citizens? 101 8. Could Kurdistan Defend Itself Militarily and Diplomatically? 107 9. Does the United States Have a Coherent Kurdistan Policy? 119 Notes 125 Acknowledgments 137 About the Author 139 iii Executive Summary wo decades ago, most US officials would have been hard-pressed Tto place Kurdistan on a map, let alone consider Kurds as allies. Today, Kurds have largely won over Washington. -

Newsletter 25

THE BRITISH INSTITUTE FOR THE STUDY OF IRAQ المعھد البريطاني لدراسة العراق NEWSLETTER NO. 25 May 2010 THE BRITISH INSTITUTE FOR THE STUDY OF IRAQ (GERTRUDE BELL MEMORIAL) REGISTERED CHARITY NO. 1135395 & NO. 219948 A company limited by guarantee registered in England and Wales No. 6966984 THE BRITISH INSTITUTE FOR THE STUDY OF IRAQ at the British Academy 10, CARLTON HOUSE TERRACE LONDON SW1Y 5AH, UK E-mail: [email protected] Tel. + 44 (0) 20 7969 5274 Fax + 44 (0) 20 7969 5401 Web-site: http://www.bisi.ac.uk The next BISI Newsletter will be published in November 2010. Brief contributions are welcomed on recent research, publications, members’ news and events. They should be sent to BISI by post or e-mail (preferred) to arrive by 15 October 2010. The BISI Administrator Joan Porter MacIver edits the Newsletter. Cover: An etching of a Sumerian cylinder seal impression by Tessa Rickards, which is the cover image of the forthcoming BISI publication, Your Praise is Sweet – A Memorial Volume for Jeremy Black from students, colleagues and friends edited by Heather D. Baker, Eleanor Robson and Gábor Zólyomi (further details p. 32). THE BRITISH INSTITUTE FOR THE STUDY OF IRAQ THE BRITISH(GERTRUDE INSTITUTE BELL FOR MEMORIAL) THE STUDY OF IRAQ STATEMENT(GERTRUDE OF BELL PUBLIC MEMORIAL) BENEFIT STATEMENT OF PUBLIC BENEFIT ‘To advance research and public education relating to Iraq and the neighbouring‘To advance countriesresearch inand anthropology, public education archaeology, relating geography,to Iraq and history, the languageneighbouring and countriesrelated disciplines in anthropology, within archaeology,the arts, humanities geography, and history, social sciences.’language and related disciplines within the arts, humanities and social sciences.’ • BISI supports high-quality research across its academic remit by • makingBISI supports grants and high-quality providing expertresearch advice across and itsinput. -

BASRA : ITS HISTORY, CULTURE and HERITAGE Basra Its History, Culture and Heritage

BASRA : ITS HISTORY, CULTURE AND HERITAGE CULTURE : ITS HISTORY, BASRA ITS HISTORY, CULTURE AND HERITAGE PROCEEDINGS OF THE CONFERENCE CELEBRATING THE OPENING OF THE BASRAH MUSEUM, SEPTEMBER 28–29, 2016 Edited by Paul Collins Edited by Paul Collins BASRA ITS HISTORY, CULTURE AND HERITAGE PROCEEDINGS OF THE CONFERENCE CELEBRATING THE OPENING OF THE BASRAH MUSEUM, SEPTEMBER 28–29, 2016 Edited by Paul Collins © BRITISH INSTITUTE FOR THE STUDY OF IRAQ 2019 ISBN 978-0-903472-36-4 Typeset and printed in the United Kingdom by Henry Ling Limited, at the Dorset Press, Dorchester, DT1 1HD CONTENTS Figures...................................................................................................................................v Contributors ........................................................................................................................vii Introduction ELEANOR ROBSON .......................................................................................................1 The Mesopotamian Marshlands (Al-Ahwār) in the Past and Today FRANCO D’AGOSTINO AND LICIA ROMANO ...................................................................7 From Basra to Cambridge and Back NAWRAST SABAH AND KELCY DAVENPORT ..................................................................13 A Reserve of Freedom: Remarks on the Time Visualisation for the Historical Maps ALEXEI JANKOWSKI ...................................................................................................19 The Pallakottas Canal, the Sealand, and Alexander STEPHANIE -

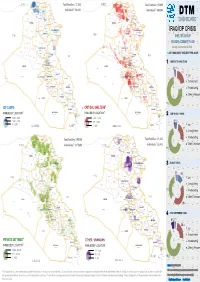

20141214 04 IOM DTM Repor

TURKEY Zakho Amedi Total Families: 27,209 TURKEY Zakho Amedi TURKEY Total Families: 113,999 DAHUK Mergasur DAHUK Mergasur Dahuk Sumel 1 Sumel Dahuk 1 Soran Individual : 163,254 Soran Individuals : 683,994 DTM Al-Shikhan Akre Al-Shikhan Akre Tel afar Choman Telafar Choman Tilkaif Tilkaif Shaqlawa Shaqlawa Al-Hamdaniya Rania Al-Hamdaniya Rania Sinjar Pshdar Sinjar Pshdar ERBIL ERBIL DASHBOARD Erbil Erbil Mosul Koisnjaq Mosul Koisnjaq NINEWA Dokan NINEWA Dokan Makhmur Sharbazher Penjwin Makhmur Sharbazher Penjwin Dabes Dabes IRAQ IDP CRISIS Al-Ba'aj SULAYMANIYAH Al-Ba'aj SULAYMANIYAH Hatra Al-Shirqat Kirkuk Hatra Al-Shirqat Kirkuk Sulaymaniya Sulaymaniya KIRKUK KIRKUK Al-Hawiga Chamchamal Al-Hawiga Chamchamal DarbandihkanHalabja SYRIA Darbandihkan SYRIA Daquq Daquq Halabja SHELTER GROUP Kalar Kalar Baiji Baiji Tooz Tooz BY DISPLACEMENT FLOW Ra'ua Tikrit SYRIA Ra'ua Tikrit Kifri Kifri January to December 9, 2014 SALAH AL-DIN Haditha Haditha SALAH AL-DIN Samarra Al-Daur Khanaqin Samarra Al-Daur Khanaqin Al-Ka'im Al-Ka'im Al-Thethar Al-Khalis Al-Thethar Al-Khalis % OF FAMILIES BY SHELTER TYPE AS OF: DIYALA DIYALA Ana Balad Ana Balad IRAN Al-Muqdadiya IRAN Al-Muqdadiya IRAN Heet Al-Fares Heet Al-Fares Tar m ia Tarm ia Ba'quba Ba'quba Adhamia Baladrooz Adhamia Baladrooz Kadhimia Kadhimia JANUARY TO MAY CRISIS KarkhAl Resafa Ramadi Ramadi KarkhAl Resafa 1 Abu Ghraib Abu Ghraib BAGHDADMada'in BAGHDADMada'in ANBAR Falluja ANBAR Falluja Mahmoudiya Mahmoudiya Badra Badra 2% 1% Al-Azezia Al-Azezia Al-Suwaira Al-Suwaira Al-Musayab Al-Musayab 21% Al-Mahawil -

Mosul Response Dashboard 20 Aug 2017

UNHCR Mosul Emergency Response Since October 2016 23 August 2017 UNHCR Co-coordinated Clusters: 1,089,564 displaced since 17 October 2016 Camp/Site Plots Tents Complete + of whom 838,608 are NFI Kits WƌŽƚĞĐƟŽŶ ƐƟůůĐƵƌƌĞŶƚůLJĚŝƐƉůĂĐĞĚ & ;ŽͲĐŽŽƌĚŝŶĂƚĞĚďLJhE,ZΘZͿ Targets:44,000 60,000 87,500 ƐƐŝƐƚĞĚďLJhE,Z KĐĐƵƉŝĞĚ DistribƵted 8,931 10,586 SŚĞůƚĞƌΘE&/ 8,931 3,360 (Co-coordinated ďLJhE,ZΘEZͿ 454,098 144,703 20,576 16,849 ( 17,294 16,398 ŝŶĚŝǀŝĚƵĂůƐ ŝŶĚŝǀŝĚƵĂůƐ Developed Plots Available assisted assisted Camp ŽŽƌĚŝŶĂƟŽŶΘ 34,671 73,554 ĂŵƉDĂŶĂŐĞŵĞŶƚ in camps ŽƵƚŽĨĐĂŵƉƐ 6,187 34,220 /ŶĐůƵĚĞƐĐŽŶŇŝĐƚͲĂīĞĐƚĞĚ EĞǁƌĞƋƵŝƌĞŵĞŶƚƐ EĞǁƌĞƋƵŝƌĞŵĞŶƚƐ ! ;ŽͲĐŽŽƌĚŝŶĂƚĞĚďLJhE,ZΘ/KDͿ ƉŽƉƵůĂƟŽŶǁŚŽǁĞƌĞ ŶĞǀĞƌĚŝƐƉůĂĐĞĚ in 2017 in 2017 Derkar dhZ<z Batifa 20km UNHCR Protection Monitoring for Mosul Response Zakho Amadiya Amedi Soran Mergasur Dahuk Ü 47,478 HHs Assessed Sumel Dahuk ^zZ/EZ 212,978 IndividƵals ZWh>/ DAHUK Akre Choman Mosul Dam Lake Shikhan Soran Choman Amalla ISLADIC Mosul Dam Nargizlia 1 B Nargizlia 2 ZEPUBLIC Tilkaif B Telafar Zelikan (n(new) OF IZAN QaymawaQ (Zelikan) B Shaqlawa 58,954 60,881 48,170 44,973 NINEWA HamdaniyaHdHamdaddaa iyaiyyay Al Hol HasanshamHaasasanshams U2 campp MosulMosuMosMooosssuulul HasanshamHasansham U3 Rania BartellaBartelllalaB B Pshdar Mosul BBBHhM2Hasanshamaanshnnssh M2 KhazerKhazehaha M1 Plots in UNHCR Constructed Camps Sinjar BChamakorChamakor As Salamiyah S y Erbil Hammamammama Al-AlilAlil 2 Al Salamiyah 2 DUKAN Occupied Plots Developed Plots Undeveloped Plots BB B RESERVOIR HammamHammH AAlAl-Alil Alil Erbil B Al ^alamiyaŚ