Border Achaeology, 2009)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 1793 Brecon & Abergavenny Canal

Transcribed intermittently in the period 1994 to 2018. Completed March 2018. E&OE B & A Canal Act, March 1793 ANNO TRICESIMO TERTIO Georgii III. Regis CAP. XCVI An Act for making and maintaining a Navigable Canal from the Town of Brecknock to the Monmouthshire Canal, near the Town of Pontypool in the County of Monmouth; and for making and maintaining Rail Ways and Stone Roads from such Canal to several Iron Works and Mines in the Counties of Brecknock and Monmouth. Preamble Whereas the making and maintaining of a Canal for the Navigation of Boats, Barges, and other Vessels, from the Town of Brecknock into the Monmouthshire Canal, at or near a Placed called Pontymoile, near the Town of Pontypool, in the County of Monmouth, will open an easy Communication between the County of Brecknock, the Town of Abergavenny, and other interior Parts of the County of Monmouth, and the several Ports and Navigations of the Kingdom, and the making and maintaining of Rail Ways, or Stone Roads, for the Passage of Waggons and other Carriages from such Canal, will open a Communication with several considerable Iron Works, Collieries, Lime Stone Quarries, and extensive Tracts of Land, abounding with Iron Ore, Coal, Lime Stone, and other Minerals, in the said Counties; whereby the Carriage and Conveyance of Coal, Lime, Iron, Timber, and all kinds of Merchandize, to and from the different Places bordering on or near the said intended Canal, and Rail Ways, or Stone Roads, will be greatly facilitated, and rendered less expensive than at present, and will tend greatly -

Chartist Newsletter 4

No 4 March 2014 Celebrating the Chartists NEWSLETTER THE 175TH ANNIVERSARY ROLLS OUT ACROSS THE REGION Newport City Council sets up ALSO in this EDITION: Chartist Commission: 4 A Dame, ex-Archbishop and retired NEW FEATURE starts this month! DIGITAL Teacher appointed CHARTISM SOURCES page 6 The Council is keen to make 2014 a How to search the ‘Northern Star’ - also ‘celebration of Chartism’ and will support the commission in its work’, announced Councillor excerpts from the ‘Western Vindicator’ Bob Bright, Leader of Newport Council BOOK of the MONTH: Voices for the Vote Shire Hall at Monmouth plans video (Shire Hall publication 2011) page 3 link with Tasmania 8 In our February edition, we boasted ONE HUNDRED & SEVENTY FIVE YEARS that we intended to reach the parts AGO During March 1839, Henry Vincent on “where Frost & Co were banished”. Tour From Bristol to Monmouth page 7 Gwent Archives starts activities in March 20th Vincent takes tea with the the Gwent Valleys. Rhondda LHS Chartist Ladies at Newport page 11 9 supporting ‘Chartist Day School’ at Pontypridd WHAT’s in NEWPORT MUSEUM? Two Silver CHARTIST HERITAGE rescued Cups for a loyal power broker page 2 at Merthyr – Vulcan House 10 restored and our NETWORKING pages 10 & 11 Before After Vulcan House, Morganstown in Merthyr Tydfil, - Now 1 WHAT’s in NEWPORT MUSEUM? SILVER CUPS PRESENTED TO THOMAS PHILLIPS Silver cup with profuse vine clusters, cover with figure finial, Silver cup with inscribed lid “presented by Benj Hall Esq., inscribed as presented “by the Committee for Conducting MP of llanover to Thomas Phillips Esq.,Jnr., as a testimony the Election for William Adams Williams Esq MP 1831” of the high estimation he entertains of his talents and of the great professional knowledge and ability WHICH HE SO DISINTERESTEDLY AND PERSERVERINGLY EXERTED FOR THE GOOD OF HIS COUNTRY during the arduous contest FOR THE UNITED BOROUGHS OF MONMOUTH, NEWPORT, AND USK, IN 1831 & FIDUS ET FIRMUS” Received for political services was usually settled without contest. -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Cabinet, 19/07/2017 16:00

Public Document Pack Agenda Cabinet Date: Wednesday, 19 July 2017 Time: 4.00 pm Venue: Committee Room 1 - Civic Centre To: Councillors D Wilcox (Chair), P Cockeram, G Giles, D Harvey, R Jeavons, D Mayer, J Mudd, R Truman and M Whitcutt Item Wards Affected 1 Apologies for Absence 2 Agenda yn Gymraeg (Pages 3 - 4) 3 Declarations of Interest 4 Minutes of the Last Meeting (Pages 5 - 10) 5 Sale of Friars Walk (Pages 11 - 24) Stow Hill 6 Director of Social Services Annual Report (Pages 25 - 78) All Wards 7 City of Democracy (Pages 79 - 118) All Wards 8 Newport Economic Network (Pages 119 - 126) All Wards 9 Wales Audit Office Action Plan (Pages 127 - 148) All Wards 10 Budget Consultation and Engagement Process (Pages 149 - 160) All Wards 11 Medium Term Financial Plan (Pages 161 - 186) All Wards 12 Revenue Budget Monitor (Pages 187 - 204) All Wards 13 21st Century Schools (Pages 205 - 226) All Wards 14 Cabinet Work Programme (Pages 227 - 232) Contact: Eleanor Mulligan, Head of Democratic Services (Interim) Tel: 01633 656656 E-mail: [email protected] Date of Issue: 12 July 2017 This page is intentionally left blank Agenda Item 2 Agenda Cabinet Dyddiad: Dydd Mercher, 19 Gorffennaf 2017 Amser: 4 y.p. Lleoliad: Ystafell Bwyllgor 1 – Y Ganolfan Ddinesig At: Cynghorwyr: D Wilcox (Cadeirydd), P Cockeram, G Giles, D Harvey, R Jeavons, D Mayer, J Mudd, R Truman a M Whitcutt Eitem Wardiau Dan Sylw 1 Agenda yn Gymraeg 2 Ymddiheuriadau am absenoldeb 3 Datganiadau o fuddiant 4 Cofnodion 5 Gwerthu Friars Walk 6 Adroddiad Blynyddol y Cyfarwyddwr -

Wales Would Have to Invent Them

Celebrating Democracy Our Voice, Our Vote, Our Freedom 170th anniversary of the Chartist Uprising in Newport. Thursday 15 October 2009 at The Newport Centre exciting opportunities ahead. We stand ready to take on bad Introduction from Paul O’Shea employers, fight exploitation and press for social justice with a clear sense of purpose. Chair of Bevan Foundation and Regional Let us put it this way, if unions did not exist today, someone Secretary , Unison Cymru / Wales would have to invent them. Employers need to talk to employees, Freedom of association is rightly prominent in every charter government needs views from the workplace and above all, and declaration of human rights. It is no coincidence that employees need a collective voice. That remains as true today, as authoritarians and dictators of left and right usually crack down it was in Newport, in November 1839. on trade unions as a priority. Look to the vicious attacks on the union movement by the Mugabe regime, the human rights abuses of Colombian trade unionists or indeed, the shooting and Electoral Reform Society incarceration of Chartists engaged in peaceful protest as a grim reminder of this eternal truth. The Electoral Reform Society is proud to support this event commemorating 170 years since the Newport Rising. The ERS A free and democratic society needs to be pluralist. There must campaigns on the need to change the voting system to a form of be checks and balances on those who wield power. There must proportional representation, and is also an active supporter Votes be a voice for everyone, not just the rich, the privileged and at 16 and involved in producing materials for the citizenship the powerful. -

Listed Buildings Detailled Descriptions

Community Langstone Record No. 2903 Name Thatched Cottage Grade II Date Listed 3/3/52 Post Code Last Amended 12/19/95 Street Number Street Side Grid Ref 336900 188900 Formerly Listed As Location Located approx 2km S of Langstone village, and approx 1km N of Llanwern village. Set on the E side of the road within 2.5 acres of garden. History Cottage built in 1907 in vernacular style. Said to be by Lutyens and his assistant Oswald Milne. The house was commissioned by Lord Rhondda owner of nearby Pencoed Castle for his niece, Charlotte Haig, daughter of Earl Haig. The gardens are said to have been laid out by Gertrude Jekyll, under restoration at the time of survey (September 1995) Exterior Two storey cottage. Reed thatched roof with decorative blocked ridge. Elevations of coursed rubble with some random use of terracotta tile. "E" plan. Picturesque cottage composition, multi-paned casement windows and painted planked timber doors. Two axial ashlar chimneys, one lateral, large red brick rising from ashlar base adjoining front door with pots. Crest on lateral chimney stack adjacent to front door presumably that of the Haig family. The second chimney is constructed of coursed rubble with pots. To the left hand side of the front elevation there is a catslide roof with a small pair of casements and boarded door. Design incorporates gabled and hipped ranges and pent roof dormers. Interior Simple cottage interior, recently modernised. Planked doors to ground floor. Large "inglenook" style fireplace with oak mantle shelf to principal reception room, with simple plaster border to ceiling. -

Report on the Administrative History of the Chartist Trials Papers

A Report on the Administrative History of the ‘Chartist Trials’ Papers Introduction: The documents now referred to as the ‘Chartist Trials’ papers, an archive collection conserved and catalogued by Newport Public Library c. 1960 in a series of twenty-five bound volumes, consist primarily of the records generated during the magistrates’ preliminary hearings conducted at the Westgate Hotel, Newport, the scene of the Chartist Rising. These hearings, held in preparation for the Chartist Trials at Monmouth in January 1840, commenced on Tuesday 5 November and were held almost continuously down to Saturday 30 November (some residual cases were heard at Monmouth on the 4 & 5 December ), before the Grand Jury for the Special Commission assembled at Shire Hall on 10 December 1839. In the course of these hearings the capital charge of high treason was initially made against fifty of the accused. The Attorney-General, Sir John Campbell, and the prosecution team subsequently reduced the number charged with high treason to a total of twenty persons (in part for reasons of practical legal management). Broadly speaking the remaining Chartists indicted for offences during the Rising were prosecuted on the lesser charges of riot and conspiracy, and sedition. The Grand Jury (sitting 10-11 Dec.) found true bills to proceed to the main trial by Petty Jury against fourteen of the twenty persons presented for the charge of high treason . Of the preliminary hearings that commenced on the morning of 5 November John Frost, Charles Waters and John Partridge were the first accused brought before the makeshift courtroom (Frost had been arrested the previous evening in the house of the printer John Partridge, by Thomas Jones Phillips). -

GT A4 Brochure

CC(3) AWE 06 CC(3) AWE 06 GWENT YOUNG PEOPLEʼS THEATRE Artistic Director Gary Meredith Administrative Director Julia Davies Tutor/Directors Stephen Badman Jain Boon John Clark Chris Durnall Lisa Harris Tutor/Stage Management George Davis-Stewart Designer Bettina Reeves GWENT THEATRE Artistic Director Gary Meredith Administrative Director Julia Davies Assistant Director Jain Boon Company Stage Manager George Davis-Stewart Designer Georgina Miles Education Officer Paul Gibbins Administrative Asstistant Chris Miller Caretaker Trevor Fallon BOARD OF DIRECTORS Chair Mick Morden Directors Jayne Davies, Denise Embrey, Sue Heathcote, Barbara Hetherington, Jenny Hood MBE, Brian Mawby, Jessica Morden, Stuart Neale, Hamish Sandison, Caroline Sheen, Llewellyn Smith, Paul Starling, Gregg Taylor, Patrons Rt Hon Neil Kinnock, Victor Spinetti Cover Design - Clive Hicks-Jenkins Photographs by Jenny Barnes and other friends of the company. Our thanks to you all. CC(3) AWE 06 50 Years of PeakGwent Performance Young People’s Theatre 1956 - 2006 Also Celebrating Gwent Theatre at 30 1976 - 2006 CC(3) AWE 06 Gwent Theatre Board would wish to take little credit for the extraordinary achievement celebrated in this brochure. We have overseen the activity of Gwent Young Peopleʼs Theatre – as an integral part of Gwent Theatre – since 1976, but 50 years of thrilling productions are the product of the enthusiasm, foresight and love of theatre that Mel Thomas devoted to its beginning, and Gary Meredith, Julia Davies, Stephen Badman and a host of talented helpers have given so generously ever since. The biographies of former members establish clearly that this has always been more than an engaging pastime for a Saturday. -

Listed Buildings 27-07-11

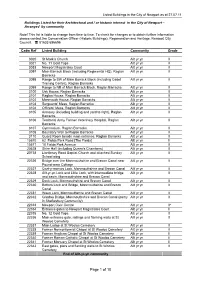

Listed Buildings in the City of Newport as at 27.07.11 Buildings Listed for their Architectural and / or historic interest in the City of Newport – Arranged by community Note! This list is liable to change from time to time. To check for changes or to obtain further information please contact the Conservation Officer (Historic Buildings), Regeneration and Heritage, Newport City Council. 01633 656656 Cadw Ref Listed Building Community Grade 3020 St Mark’s Church Allt yr yn II 3021 No. 11 Gold Tops Allt yr yn II 3033 Newport Magistrates Court Allt yr yn II 3097 Main Barrack Block (including Regimental HQ), Raglan Allt yr yn II Barracks 3098 Range to SW of Main Barrack Block (including Cadet Allt yr yn II Training Centre), Raglan Barracks 3099 Range to NE of Main Barrack Block, Raglan Barracks Allt yr yn II 3100 Usk House, Raglan Barracks Allt yr yn II 3101 Raglan House, Raglan Barracks Allt yr yn II 3102 Monmouth House, Raglan Barracks Allt yr yn II 3103 Sergeants' Mess, Raglan Barracks Allt yr yn II 3104 Officers' Mess, Raglan Barracks Allt yr yn II 3105 Armoury (including building and yard to right), Raglan Allt yr yn II Barracks 3106 Territorial Army Former Veterinary Hospital, Raglan Allt yr yn II Barracks 3107 Gymnasium, Raglan Barracks Allt yr yn II 3108 Boundary Wall to Raglan Barracks Allt yr yn II 3110 Guard Room beside main entrance, Raglan Barracks Allt yr yn II 15670 62 Fields Park Road [The Fields] Allt yr yn II 15671 18 Fields Park Avenue Allt yr yn II 20528 Shire Hall (including Queen's Chambers) Allt yr yn II 20738 Llanthewy -

Members of the Ellsworth and Mcarthur Handcart Companies of 1856 Compiled by Susan Easton Black © 1982, Copyright Susan Easton Black

Members of the Ellsworth and McArthur Handcart Companies of 1856 Compiled by Susan Easton Black © 1982, Copyright Susan Easton Black . To my sons… Then in a moment to my view The stranger started from disguise; The tokens in his hands I knew; The Savior stood before mine eyes. He spake, and my poor name he named, "Of me thou hast not been ashamed; These deeds shall thy memorial be, Fear not, thou didst them unto me." A Poor Wayfaring Man of Grief Preface to Members of the Ellsworth and McArthur Handcart Companies of 1856 It has been my purpose in preparing this compilation of vital statistical information to show my appreciation for the Ellsworth and McArthur Handcart Companies. Unfortunately, some of the statistical information recorded by the members and their posterity was inaccurate, conflicting, or incomplete. Where possible, research was done to alleviate this problem The compiled information was gathered and used as a secondary source for submitting pioneer names for temple work to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Genealogical Department. As a result of this study over 200 ordinances were identified and performed for members of the Ellsworth and McArthur Handcart Companies in the Provo Temple. Members of the First Handcart Company Edmund Ellsworth, Captain Argyle, Joseph II Born: 12 September 1818 in Market Bosworth, Lancashire, England Son of Joseph Argyle and Francis (Frances) Smith Married: 24 December 1840 to Rebecca Jane Finch in Birmingham, Warwickshire, England Died: 26 September 1905 in West Bountiful, Davis, -

Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = the National Library of Wales Cymorth

Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Cymorth chwilio | Finding Aid - Maybery Collection, (GB 0210 MAYBERY) Cynhyrchir gan Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Argraffwyd: Mai 03, 2017 Printed: May 03, 2017 Wrth lunio'r disgrifiad hwn dilynwyd canllawiau ANW a seiliwyd ar ISAD(G) Ail Argraffiad; rheolau AACR2; ac LCSH Description follows ANW guidelines based on ISAD(G) 2nd ed.;AACR2; and LCSH https://archifau.llyfrgell.cymru/index.php/maybery-collection-2 archives.library .wales/index.php/maybery-collection-2 Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Allt Penglais Aberystwyth Ceredigion United Kingdom SY23 3BU 01970 632 800 01970 615 709 [email protected] www.llgc.org.uk Maybery Collection, Tabl cynnwys | Table of contents Gwybodaeth grynodeb | Summary information .............................................................................................. 3 Hanes gweinyddol / Braslun bywgraffyddol | Administrative history | Biographical sketch ......................... 3 Natur a chynnwys | Scope and content .......................................................................................................... 4 Trefniant | Arrangement .................................................................................................................................. 4 Nodiadau | Notes ............................................................................................................................................. 4 Pwyntiau mynediad | Access points -

Visitor Assistant Shire Hall Monmouth

Come and join the team! ADVERT ROLE TITLE: Visitor Assistant, Shire Hall, Monmouth ADVERT TEXT: The Shire Hall in Agincourt Square, Monmouth is a prominent Grade I listed building in the town centre. Built in 1724, the Shire Hall was formerly the centre for the Assize Courts and Quarter Sessions for Monmouthshire. In 1839/40, the court was the location of the trial of the Chartist leader John Frost and others for high treason for their part in the Newport Rising. To day it is a top visitor attraction within the town. We are looking for a motivated individual who loves working with people and will take pride in contributing to purpose and the running of Shire Hall. With your endless passion for our work, you’ll help with the site presentation, offer tourist information for visitors; carry out daily checks to ensure the site is presented to a hight standard, and your passion will inspire others to love this beautiful place as much as you do. We want you to engage with visitors, making time to talk to them, not rushing away to the next task. As an easily identifiable member of the Shire Hall team, on your best day you will be creating lasting memories for everyone. We want to ensure that special places like Shire Hall are here to be both protected and enjoyed by everyone for ever. After all, your passion and dedication could fire the imagination that makes a visitor become a supporter for the rest of their life. MonLife believes that people deserve more than just ‘good service’, but an amazing experience they’ll never forget, and we are looking for like-minded people to join us – are you ready? POST ID: ENTATT10 LOCATION: Shire Hall, Monmouth GRADE: BAND D £20,903.00 - £22,627.00 pro rata HOURS: 18.5 hours per week TEMPORARY: No WORK PATTERN: 18.5 hours a week. -

The Cry of the Cymry: the Linguistic, Literary, and Legendary Foundations of Welsh Nationalism As It Developed Throughout the 19Th Century

Abilene Christian University Digital Commons @ ACU ACU Student Research, Theses, Projects, and Honors College Dissertations 4-2018 The rC y of the Cymry: The Linguistic, Literary, and Legendary Foundations of Welsh Nationalism as it Developed Throughout the 19th Century McKinley Terry Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/honors The Cry of the Cymry: The Linguistic, Literary, and Legendary Foundations of Welsh Nationalism as it Developed Throughout the 19th Century An Honors College Project Thesis Presented to The Department of History and Global Studies Abilene Christian University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Honors Scholar by McKinley Terry April 2018 Copyright 2018 McKinley Terry ALL RIGHTS RESERVED This Project Thesis, directed and approved by the candidate’s committee, has been accepted by the Honors College of Abilene Christian University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the distinction HONORS SCHOLAR Dr. Jason Morris, Dean of the Honors College _______________________ Date Advisory Committee Dr. Kelly Elliott, Committee Chair Dr. William Carroll, Committee Member Dr. Ron Morgan, Department Head Abstract This paper examines the development of a national identity in Wales throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, beginning with the effects of the French Revolution and ending with the aftermath of the First World War. Using cultural theories such as Anderson’s “Imagined Communities” and Hobsawm and Ranger’s “Imagined Traditions,” this paper pays special attention to the Celtic traditions and myths that Welsh leaders utilized to cultivate a sense of nationalism and foster a political identity that gained prominence in the nineteenth century. This nationalism will also be presented in the context of cultural changes that Wales faced during this time, especially industrialization and Romanticism.