The Most Chartist of All the Factory Towns

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wales Would Have to Invent Them

Celebrating Democracy Our Voice, Our Vote, Our Freedom 170th anniversary of the Chartist Uprising in Newport. Thursday 15 October 2009 at The Newport Centre exciting opportunities ahead. We stand ready to take on bad Introduction from Paul O’Shea employers, fight exploitation and press for social justice with a clear sense of purpose. Chair of Bevan Foundation and Regional Let us put it this way, if unions did not exist today, someone Secretary , Unison Cymru / Wales would have to invent them. Employers need to talk to employees, Freedom of association is rightly prominent in every charter government needs views from the workplace and above all, and declaration of human rights. It is no coincidence that employees need a collective voice. That remains as true today, as authoritarians and dictators of left and right usually crack down it was in Newport, in November 1839. on trade unions as a priority. Look to the vicious attacks on the union movement by the Mugabe regime, the human rights abuses of Colombian trade unionists or indeed, the shooting and Electoral Reform Society incarceration of Chartists engaged in peaceful protest as a grim reminder of this eternal truth. The Electoral Reform Society is proud to support this event commemorating 170 years since the Newport Rising. The ERS A free and democratic society needs to be pluralist. There must campaigns on the need to change the voting system to a form of be checks and balances on those who wield power. There must proportional representation, and is also an active supporter Votes be a voice for everyone, not just the rich, the privileged and at 16 and involved in producing materials for the citizenship the powerful. -

Listed Buildings Detailled Descriptions

Community Langstone Record No. 2903 Name Thatched Cottage Grade II Date Listed 3/3/52 Post Code Last Amended 12/19/95 Street Number Street Side Grid Ref 336900 188900 Formerly Listed As Location Located approx 2km S of Langstone village, and approx 1km N of Llanwern village. Set on the E side of the road within 2.5 acres of garden. History Cottage built in 1907 in vernacular style. Said to be by Lutyens and his assistant Oswald Milne. The house was commissioned by Lord Rhondda owner of nearby Pencoed Castle for his niece, Charlotte Haig, daughter of Earl Haig. The gardens are said to have been laid out by Gertrude Jekyll, under restoration at the time of survey (September 1995) Exterior Two storey cottage. Reed thatched roof with decorative blocked ridge. Elevations of coursed rubble with some random use of terracotta tile. "E" plan. Picturesque cottage composition, multi-paned casement windows and painted planked timber doors. Two axial ashlar chimneys, one lateral, large red brick rising from ashlar base adjoining front door with pots. Crest on lateral chimney stack adjacent to front door presumably that of the Haig family. The second chimney is constructed of coursed rubble with pots. To the left hand side of the front elevation there is a catslide roof with a small pair of casements and boarded door. Design incorporates gabled and hipped ranges and pent roof dormers. Interior Simple cottage interior, recently modernised. Planked doors to ground floor. Large "inglenook" style fireplace with oak mantle shelf to principal reception room, with simple plaster border to ceiling. -

GT A4 Brochure

CC(3) AWE 06 CC(3) AWE 06 GWENT YOUNG PEOPLEʼS THEATRE Artistic Director Gary Meredith Administrative Director Julia Davies Tutor/Directors Stephen Badman Jain Boon John Clark Chris Durnall Lisa Harris Tutor/Stage Management George Davis-Stewart Designer Bettina Reeves GWENT THEATRE Artistic Director Gary Meredith Administrative Director Julia Davies Assistant Director Jain Boon Company Stage Manager George Davis-Stewart Designer Georgina Miles Education Officer Paul Gibbins Administrative Asstistant Chris Miller Caretaker Trevor Fallon BOARD OF DIRECTORS Chair Mick Morden Directors Jayne Davies, Denise Embrey, Sue Heathcote, Barbara Hetherington, Jenny Hood MBE, Brian Mawby, Jessica Morden, Stuart Neale, Hamish Sandison, Caroline Sheen, Llewellyn Smith, Paul Starling, Gregg Taylor, Patrons Rt Hon Neil Kinnock, Victor Spinetti Cover Design - Clive Hicks-Jenkins Photographs by Jenny Barnes and other friends of the company. Our thanks to you all. CC(3) AWE 06 50 Years of PeakGwent Performance Young People’s Theatre 1956 - 2006 Also Celebrating Gwent Theatre at 30 1976 - 2006 CC(3) AWE 06 Gwent Theatre Board would wish to take little credit for the extraordinary achievement celebrated in this brochure. We have overseen the activity of Gwent Young Peopleʼs Theatre – as an integral part of Gwent Theatre – since 1976, but 50 years of thrilling productions are the product of the enthusiasm, foresight and love of theatre that Mel Thomas devoted to its beginning, and Gary Meredith, Julia Davies, Stephen Badman and a host of talented helpers have given so generously ever since. The biographies of former members establish clearly that this has always been more than an engaging pastime for a Saturday. -

Listed Buildings 27-07-11

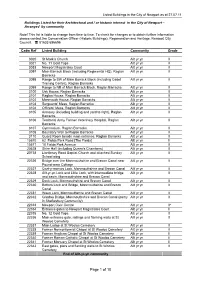

Listed Buildings in the City of Newport as at 27.07.11 Buildings Listed for their Architectural and / or historic interest in the City of Newport – Arranged by community Note! This list is liable to change from time to time. To check for changes or to obtain further information please contact the Conservation Officer (Historic Buildings), Regeneration and Heritage, Newport City Council. 01633 656656 Cadw Ref Listed Building Community Grade 3020 St Mark’s Church Allt yr yn II 3021 No. 11 Gold Tops Allt yr yn II 3033 Newport Magistrates Court Allt yr yn II 3097 Main Barrack Block (including Regimental HQ), Raglan Allt yr yn II Barracks 3098 Range to SW of Main Barrack Block (including Cadet Allt yr yn II Training Centre), Raglan Barracks 3099 Range to NE of Main Barrack Block, Raglan Barracks Allt yr yn II 3100 Usk House, Raglan Barracks Allt yr yn II 3101 Raglan House, Raglan Barracks Allt yr yn II 3102 Monmouth House, Raglan Barracks Allt yr yn II 3103 Sergeants' Mess, Raglan Barracks Allt yr yn II 3104 Officers' Mess, Raglan Barracks Allt yr yn II 3105 Armoury (including building and yard to right), Raglan Allt yr yn II Barracks 3106 Territorial Army Former Veterinary Hospital, Raglan Allt yr yn II Barracks 3107 Gymnasium, Raglan Barracks Allt yr yn II 3108 Boundary Wall to Raglan Barracks Allt yr yn II 3110 Guard Room beside main entrance, Raglan Barracks Allt yr yn II 15670 62 Fields Park Road [The Fields] Allt yr yn II 15671 18 Fields Park Avenue Allt yr yn II 20528 Shire Hall (including Queen's Chambers) Allt yr yn II 20738 Llanthewy -

YGI2 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

YGI2 bus time schedule & line map YGI2 Newport Bus Station - Ysgol Gyfun Gwent Iscoed View In Website Mode The YGI2 bus line (Newport Bus Station - Ysgol Gyfun Gwent Iscoed) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Duffryn: 7:30 AM (2) Newport: 3:05 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest YGI2 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next YGI2 bus arriving. Direction: Duffryn YGI2 bus Time Schedule 34 stops Duffryn Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 7:30 AM Friars Walk 10, Newport 1-7 Friars Walk Shopping Centre, Newport Tuesday 7:30 AM North Street, Newport Wednesday 7:30 AM North Street, Newport Thursday 7:30 AM Havelock Street, Newport Friday 7:30 AM Havelock Street, Newport Saturday Not Operational St Woolo`S Cathedral, Newport Severn Terrace, Newport Stow Park Crescent, Stow Park YGI2 bus Info Handpost, Stow Park Direction: Duffryn Bus Lane, Newport Stops: 34 Trip Duration: 45 min St John the Baptist, Caerau Park Line Summary: Friars Walk 10, Newport, North Ombersley Lane, Newport Street, Newport, Havelock Street, Newport, St Woolo`S Cathedral, Newport, Stow Park Crescent, Coed Melyn Park, Caerau Park Stow Park, Handpost, Stow Park, St John the Baptist, Caerau Park, Coed Melyn Park, Caerau Park, Nant Coch Drive, Glasllwch Nant Coch Drive, Glasllwch, Melbourne Way, Glasllwch, Junior School, Glasllwch, Quebec Close, Melbourne Way, Glasllwch Glasllwch, Vancouver Drive, Glasllwch, Castle Park Close, Glasllwch, Post O∆ce, Stelvio Park, Melfort Junior School, Glasllwch Gardens, -

Register of Buildings at Risk June 2009

Newport City Council – Register Of Buildings At Risk June 2009 Contents Page 1.0 Summary 4 2.0 Introduction 4 3.0 Purpose of the Register 5 4.0 An overview of Buildings at Risk in Newport 2003 - 2009 7 5.0 How the register is compiled 8 6.0 How the register is used 11 7.0 How the register is set out 11 8.0 Register of Buildings at Risk 2009 – Part 1: Lists of information 12 8.1 List of buildings included in Register of Buildings at Risk 2009 13 8.2 List of Buildings Removed from the Register during 2003 – 2008 17 8.3 List of Buildings Added to the Register during 2003 - 2008 19 8.4 List of Buildings whose At Risk Category has been Reduced during 2003 – 2008 21 8.5 List of Buildings whose At Risk Category has been Increased during 2003 – 2008 22 9.0 The Register of Buildings at Risk 2009 – 23 Part 2: Overview of each Building at Risk 9.1 Alway Community 24 9.2 Allt Yr Yn Community 25 9.3 Beechwood Community 29 9.4 Caerleon Community 30 9.5 Coedkernew Community 35 9.6 Goldcliff Community 36 9.7 Graig Community 39 9.8 Langstone Community 42 9.9 Liswerry Community 46 9.10 Llanvaches Community 47 9.11 Llanwern Community 48 9.12 Malpas Community 49 - 2 - Newport City Council – Register Of Buildings At Risk June 2009 9.13 Nash Community 49 9.14 Pillgwenlly Community 50 9.15 Rogerstone Community 52 9.16 St. -

1839 “Chartist Spring” Kicking Off

No 5 April 2014 Celebrating the Chartists NEWSLETTER 1839 “CHARTIST SPRING” KICKING OFF John Frost Removed as Magistrate ALSO in this EDITION: by Home Secretary Government 2 convinced Frost was linked with ‘physical Digital Chartism – Follow the Story of the 1839 force’militants. Chartist Rising on Twitter.TWEETS available daily throughout the 175th Anniversary Year page 2 Henry Vincent – 25 Years Old - Roused Support For The Charter. 3 Thousands on BOTH SIDES of the SEVERN From the Collections of NEWPORT MUSEUM turn out to hear him. – poster/broadsheet written by Vincent, published by John Partridge, Newport printer, April 1839 Devizes- special constables started a page 5 riot! Vincent injured. 4 Chartist Art: Caerleon Quilter is making Chartist banner - FREE Workshop available Vincent’s Tour Of The Coal Field and Also article about Dr. Rowan’s views on new led night time torch lit demos at Newport Chartist artwork for Newport page 7 5 He was a marked man watched by Thomas Phillips’ agents. Video Link with Tasmania - Shire Hall making first moves page 9 In the last days of APRIL –the anti chartists rallied and magistrates searched 6 for arms and collated reports of seditious Gwent Archives: ‘Trails to Trials’ Taster Days – speeches. London policemen sent Sign up to a FREE Session in May at Blaina or at to Llanidloes enraged locals and Tredegar + Archive visit page 10 Chartists took control of the town The 175th Anniversary – calendar of events 2014 page 10 NETWORKING page 12 1 ‘DIGITAL CHARTISM’ TWEET ‘ChartistsLive’ – and follow the events as they happened 175 years ago THE ‘CHARTIST SPRING’ breaks out MARCH-APRIL 1839 GO TO https://twitter.com/ChartistsLive The Tweets started 10th March TWEETS authored by David Howell; “Chartist Spring” Storyline by Les James 21 March TWEETS # Breaking - John Frost has been removed as a magistrate # This seems to be following on from the arguments between Frost and Lord John Russell # Details are still sketchy, but a response from the Convention to the removal of Frost as a magistrate is expected shortly. -

56 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

56 bus time schedule & line map 56 Tredegar - Newport View In Website Mode The 56 bus line (Tredegar - Newport) has 5 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Blackwood: 7:00 PM - 10:30 PM (2) Blackwood: 10:45 PM (3) Markham: 10:20 AM - 6:20 PM (4) Newport: 5:52 AM - 9:45 PM (5) Tredegar: 6:45 AM - 9:30 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 56 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 56 bus arriving. Direction: Blackwood 56 bus Time Schedule 52 stops Blackwood Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 7:00 PM - 10:30 PM Market Square 20, Newport Tuesday 7:00 PM - 10:30 PM Queensway Q6, Newport Queensway, Newport Wednesday 7:00 PM - 10:30 PM Civic Centre South, Clytha Park Thursday 7:00 PM - 10:30 PM Oakƒeld Road, Newport Friday 7:00 PM - 10:30 PM Hilla Road, Caerau Park Saturday 7:00 PM - 10:30 PM Hilla Road, Newport St John the Baptist, Caerau Park Coed Melyn Park, Caerau Park 56 bus Info Direction: Blackwood Nant Coch Drive, Glasllwch Stops: 52 Trip Duration: 45 min Melbourne Way, Glasllwch Line Summary: Market Square 20, Newport, Queensway Q6, Newport, Civic Centre South, Clytha Glasllwch Crescent, Glasllwch Park, Hilla Road, Caerau Park, St John the Baptist, Caerau Park, Coed Melyn Park, Caerau Park, Nant Post O∆ce, High Cross Coch Drive, Glasllwch, Melbourne Way, Glasllwch, Glasllwch Crescent, Glasllwch, Post O∆ce, High 101 Glasllwch Crescent, Rogerstone Community Cross, Cwm Lane, High Cross, Rising Sun, Cwm Lane, High Cross Rogerstone, Ruskin Avenue, Rogerstone, Tredegar Arms, -

William Weir

By Amy Moore with Ray Moore AMY’S HERITAGE BOOK 3 THE WEIR STORY Trilogy Book 3 The Weir Story By Amy Moore with Ray Moore 2011 2 AMY’S HERITAGE BOOK 3 THE WEIR STORY © Ray Moore 2011. Unless stated otherwise, the Copyright © of this publication is held by Ray Moore. Reproduction or reuse of this material for commercial purposes is forbidden without written permission. ([email protected]) Published by: Kyema Publishing Kyema publishing only publishes Ebooks online. For more information contact: [email protected] National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Moore, Amy, 1908-2005. Title: The Weir story [electronic resource] / Amy Moore ; with Ray Moore. ISBN: 978-0-9871827-6-0 (ebook) Series: Amy's heritage trilogy ; Book 3. Subjects: Moore, Amy, 1908-2005--Family. Weir, Robert. Scotland--Genealogy. Wales--Genealogy. Australia--Genealogy. Other Authors/Contributors: Moore, Ray, 1935- Dewey Number: 929.20994 3 AMY’S HERITAGE BOOK 3 THE WEIR STORY Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................4 SOUTH WALES in the 19th Century ......................................................................................6 Brynmaur ...........................................................................................................................6 The Iron Works of Nantyglo ...............................................................................................6 Painting of the iron works at -

Christianity in Newport

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Archive, E-theses Repository CHRISTIANITY IN NEWPORT By BEATRICE NAMBUYA BALIBALI MUSINDI A Thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham For the Degree of MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Theology and Religion School of Historical Studies The University of Birmingham September 2014 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis lays the groundwork for Christian congregations engaged in mission. It emerged from my shared experience and reflections of the Christians in Newport engaged in Mission. The focal point of exploration of the thesis was how Christians in Newport in South Wales defined their Christian task and how this affected their expression in the Communities where they lived. This thesis seeks to give a voice to the views of the People in Newport. A detailed overview of the historical and current status is explored and described. This reveals a considerable change and adaptation in missiology, Church expression and new forms of church. The current experience of some groups of Christians in Newport is described based on extensive fieldwork. -

Maesruddud – 'A Jewel Stuck Into a Lump of Lead'

No. 54 Spring 2009 Maesruddud – ‘A Jewel Stuck into a Lump of Lead’ by Phil Jayne In his autobiography ‘The Life and Works of an English come into being? What were the factors that led to one of the Landscape Architect’, Thomas Mawson, writing about his work in leading garden designers of his day being commissioned to design 1907, made the following observation on a commission in South a garden in the middle of this industrial area? Wales: Maesruddud was the home of the Williams family and, in “A very difficult but not entirely unsuccessful piece of work was order to begin to understand how the garden developed, we need the garden at Maesruddud, which stood in the centre of a to tale a look at the history of the family itself. They do not appear rapidly growing colliery area not far from Newport, to have been a ‘grand’ family, although Maesruddud at the Monmouthshire. The very thought of collieries seems beginning of the nineteenth century was a prosperous farm, with incompatible with gardens, but my client, Mr T. Brewer Williams, was himself a colliery proprietor, who considered it his duty to live in the neighbourhood and in the old family home with all its disadvantages, which were intensified by an elevated windswept site resting upon a poor clay soil. The original house, which possessed no architectural interest, was much enlarged and invested with a definite architectural character by my client’s architect, Mr Edward Warren. The plan of this garden, which is a fair criterion of my ideal of the nature and extent of a garden at this time, is illustrated in ‘The Art and Craft of Garden Making’. -

Newport Coast Path English

Newport Coast Path 1 Newport Coast Path Points of Interest The Coast Path of Wales is East Coast Section page 4–11 870 miles. Redwick The Newport Whitson Coast Path Goldcliff Sea Wall & Priory Section is Wetlands Nature Reserve 23 miles/ 32km of this. The East Usk Lighthouse The Wetlands Centre Great Traston Meadows Reserve Mid-section page 12–17 The Docks The Newport Transporter Bridge The City Bridge (SDR) The Newport City Footbridge Riverfront Arts Centre Steel Wave Newport Castle West Coast section page 18–23 Tredegar House The West Usk Lighthouse The Gout at Peterstone Peterstone Church * Site of Special 2 When walking, refer to the OS Map 152 Newport & Pontypool Scientific Interest 1 A dramatic historical Canada geese landscape The Gwent Levels have been designated as Sites “…compensation land, we call this, as close as we’ll get of Special Scientific Interest. The land has been to a clean start, from scratch, laid, layered at our feet” reclaimed from the sea. At the end of the Iron from The Margin © Philip Gross Age – about 2,000 years ago – this was a tidally inundated saltmarsh. The challenges of a tide that ebbed and flowed more than two miles The Wales Coast Path is 870 miles long. It begins at inland and the manipulation of the land so that Chepstow on the banks of the Wye and finishes beside it could be safe for settlement and cultivation has shaped the history of the region. Since the River Dee a few miles from Cheshire. Roman times imaginative engineering feats The Newport section of the path crosses the Caldicot have protected homes, pastures and domestic Coast Path animals, as well as rare breeds of birds, flowers and Wentloog Levels to meet the City of Newport.