The Pulenu'u in Samoa the Transformation of An

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Community Integrated Management Plan Palauli East, Savaii

Community Integrated Management Plan Palauli East, Savaii Implementation Guidelines 2018 COMMUNITY INTEGRATED MANAGEMENT PLAN IMPLEMENTATION GUIDELINES Foreword It is with great pleasure that I present the new Community Integrated Management (CIM) Plans, formerly known as Coastal Infrastructure Management (CIM) Plans. The revised CIM Plans recognizes the change in approach since the first set of fifteen CIM Plans were developed from 2002-2003 under the World Bank funded Infrastructure Asset Management Project (IAMP) , and from 2004-2007 for the remaining 26 districts, under the Samoa Infrastructure Asset Management (SIAM) Project. With a broader geographic scope well beyond the coastal environment, the revised CIM Plans now cover all areas from the ridge-to-reef, and includes the thematic areas of not only infrastructure, but also the environment and biological resources, as well as livelihood sources and governance. The CIM Strategy, from which the CIM Plans were derived from, was revised in August 2015 to reflect the new expanded approach and it emphasizes the whole of government approach for planning and implementation, taking into consideration an integrated ecosystem based adaptation approach and the ridge to reef concept. The timeframe for implementation and review has also expanded from five years to ten years as most of the solutions proposed in the CIM Plan may take several years to realize. The CIM Plan is envisaged as the blueprint for climate change interventions across all development sectors – reflecting the programmatic approach to climate change adaptation taken by the Government of Samoa. The proposed interventions outlined in the CIM Plans are also linked to the Strategy for the Development of Samoa 2016/17 – 2019/20 and the relevant ministry sector plans. -

Conflicting Power Paradigms in Samoa's

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. CONFLICTING POWER PARADIGMS IN SAMOA’S “TRADITIONAL DEMOCRACY” FROM TENSION TO A PROCESS OF HARMONISATION? A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science at Massey University, Albany, New Zealand Christina La’alaai-Tausa 2020 COPYRIGHT Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. 2 ABSTRACT This research argues that the tension evident between western democracy and Samoa’s traditional leadership of Fa’amatai has led to a power struggle due to the inability of the government to offer thorough civic education through dialectical exchange, proper consultation, discussion and information sharing with village council leaders and their members. It also argues that Fa’amatai are being disadvantaged as the government and the democratic system is able to manipulate cultural practices and protocols to suit their political needs, whereas village councils are not recognized or acknowledged by the democratic system (particularly the courts), despite cultural guidelines and village laws providing stability for communities and the country. In addition, it claims that, despite western academics’ arguments that Samoa’s traditional system is a barrier to a fully-fledged democracy, Samoa’s Fa’amatai in theory and practice in fact proves to be more democratic than the democratic status quo. -

Samoa Visitor Survey

Samoa International Visitor Survey January – June 2018 Prepared for Samoa Tourism Authority by New Zealand Tourism Research Institute Auckland University of Technology www.nztri.org October 2018 Acknowledgements NZTRI would like to acknowledge the Samoa Tourism Authority (special mention to Kitiona Pogi, Dulcie Wong Sin, Jeddah Leavai and the broader email collection and processing team) and Samoa Immigration for their support in this ongoing research. This report was prepared by Simon Milne, Mindy Sun, Jeannie Yi, Caroline Qi, and Birthe Bakker. ii Executive Summary This report focuses on the characteristics, expectations and expenditure patterns of international tourists who visited Samoa by air between 1 January and 30 June 2018. The data presented is collected from an online departure survey (http://www.samoasurvey.com/). There were 3,297 individual respondents to the survey (5 % of visitors during the period) - representing a total of 5,899 adults and 1,501 children in terms of local expenditure analysis (the latter figure equates to 11% of all visitors during the period – based on national visitor arrival data from the Samoa Bureau of Statistics). The initial survey period of 1 January and 30 June 2018 acts as a pilot to refine and develop the survey further. During this survey period we registered good responses from all markets with the exception of visitors from American Samoa, this market has therefore been removed from the current analysis. The survey invitation has now been amended to specifically encourage, visitors from American Samoa to complete the survey and the market will be incorporated in future reporting. Three in five (60%) of visitors surveyed come from New Zealand with 23% coming from Australia. -

Of Agriculture and the Rural Sector in Samoa

COUNTRY GENDER ASSESSMENT OF AGRICULTURE AND THE RURAL SECTOR IN SAMOA COUNTRY GENDER ASSESSMENT OF AGRICULTURE AND THE RURAL SECTOR IN SAMOA Published by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and the Pacific Community Apia, 2019 Required citation: FAO and SPC. 2019. Country gender assessment of agriculture and the rural sector in Samoa. Apia. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) or the Pacific Community (SPC) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO or SPC in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO or SPC. ISBN 978-92-5-131824-9 [FAO] ISBN 978-982-00-1199-1 [SPC] © FAO and SPC, 2019 Some rights reserved. This work is made available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo/legalcode). Under the terms of this licence, this work may be copied, redistributed and adapted for non-commercial purposes, provided that the work is appropriately cited. -

47320-001: Involuntary Resettlement Due Diligence Report

Involuntary Resettlement Due Diligence Report July 2015 Proposed Grant Samoa: Submarine Cable Project This Involuntary Resettlement Due Diligence Report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or Staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Proposed Grant Samoa: Samoa Submarine Cable Project DUE DILIGENCE REPORT ON INVOLUNTARY RESETTLEMENT- Fagali’i and Tuasivi Villages, Samoa 8 June 2015 I. Introduction 1. This due diligence report (DDR) on involuntary resettlement describes: Brief project background; Component activities; Current status of land ownership or use; and Identification of land requirement for sub-project components and potential issues. II. Background and Objectives 2. The Government of the Independent State of Samoa (the government) has requested the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and the World Bank (WB) to support market development and core infrastructure investments aimed at improving access to information and communications technology (ICT). A key component of this support is the planned investment in a submarine cable system (SCS) to connect Samoa to regional/global communications infrastructure. 3. The objective of the Samoa Submarine -

American Samoa

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Texas A&M University THE LITHICS OF AGANOA VILLAGE (AS-22-43), AMERICAN SAMOA: A TEST OF CHEMICAL CHARACTERIZATION AND SOURCING TUTUILAN TOOL-STONE A Thesis by CHRISTOPHER THOMAS CREWS Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2008 Anthropology THE LITHICS OF AGANOA VILLAGE (AS-22-43), AMERICAN SAMOA: A TEST OF CHEMICAL CHARACTERIZATION AND SOURCING TUTUILAN TOOL-STONE A Thesis by CHRISTOPHER THOMAS CREWS Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Approved by: Chair of Committee, Suzanne L. Eckert Committee Members, Ted Goebel Frederic Pearl Head of Department, Donny L. Hamilton May 2008 Major Subject: Anthropology iii ABSTRACT The Lithics of Aganoa Village (AS-22-43), American Samoa: A Test of Chemical Characterization and Sourcing Tutuilan Tool-Stone. (May 2008) Christopher Thomas Crews, B.A., Colorado College Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. Suzanne L. Eckert The purpose of this thesis is to present the morphological and chemical analyses of the lithic assemblage recovered from Aganoa Village (AS-22-43), Tutuila Island, American Samoa. Implications were found that include the fact that Aganoa Village did not act as a lithic workshop, new types of tools that can be included in the Samoan tool kit, a possible change in subsistence strategies through time at the site, and the fact that five distinct, separate quarries were utilized at different stages through the full temporal span of residential activities at the village. -

Bill Analysis

HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES FINAL BILL ANALYSIS BILL #: HB 1013 FINAL HOUSE FLOOR ACTION: SUBJECT/SHORT Daylight Saving Time 103 Y’s 11 N’s TITLE SPONSOR(S): Nuñez; Fitzenhagen and others GOVERNOR’S Approved ACTION: COMPANION CS/CS/SB 858 BILLS: SUMMARY ANALYSIS HB 1013 passed the House on February 14, 2018, and subsequently passed the Senate on March 6, 2018. The bill declares the Legislature’s intent to observe Daylight Saving Time year-round throughout the entire state if federal law is amended to permit states to take such action. The bill does not appear to have a fiscal impact. The bill was approved by the Governor on March 23, 2018, ch. 2018-99, L.O.F., and will become effective on July 1, 2018. This document does not reflect the intent or official position of the bill sponsor or House of Representatives. STORAGE NAME: h1013z1.LFV.docx DATE: March 28, 2018 I. SUBSTANTIVE INFORMATION A. EFFECT OF CHANGES: Present Situation The Standard Time Act of 1918 In 1918, the United States enacted the Standard Time Act, which adopted a national standard measure of time, created five standard time zones across the continental U.S., and instituted Daylight Saving Time (DST) nationwide as a war effort during World War I.1 DST advanced standard time by one hour from the last Sunday in March to the last Sunday in October.2 DST was repealed after the war but the standard time provisions remained in place.3 During World War II, a national DST standard was revived and extended year-round from 1942 to 1945.4 Uniform Time Act of 1966 Following World War -

Savai'i Volcano

A Visitor’s Field Guide to Savai’i – Touring Savai’i with a Geologist A Visitor's Field Guide to Savai’i Touring Savai'i with a Geologist Warren Jopling Page 1 A Visitor’s Field Guide to Savai’i – Touring Savai’i with a Geologist ABOUT THE AUTHOR AND THIS ARTICLE Tuapou Warren Jopling is an Australian geologist who retired to Savai'i to grow coffee after a career in oil exploration in Australia, Canada, Brazil and Indonesia. Travels through Central America, the Andes and Iceland followed by 17 years in Indonesia gave him a good understanding of volcanology, a boon to later educational tourism when explaining Savai'i to overseas visitors and student groups. His 2014 report on Samoa's Geological History was published in booklet form by the Samoa Tourism Authority as a Visitor's Guide - a guide summarising the main geological events that built the islands but with little coverage of individual natural attractions. This present article is an abridgement of the 2014 report and focuses on Savai'i. It is in three sections; an explanation of plate movement and hotspot activity for visitors unfamiliar with plate tectonics; a brief summary of Savai'i's geological history then an island tour with some geologic input when describing the main sites. It is for nature lovers who would appreciate some background to sightseeing. Page 1 A Visitor’s Field Guide to Savai’i – Touring Savai’i with a Geologist The Pacific Plate, The Samoan Hotspot, The Samoan Archipelago The Pacific Plate, the largest of the Earth's 16 major plates, is born along the East Pacific Rise. -

Samoa Socio-Economic Atlas 2011

SAMOA SOCIO-ECONOMIC ATLAS 2011 Copyright (c) Samoa Bureau of Statistics (SBS) 2011 CONTACTS Telephone: (685) 62000/21373 Samoa Socio Economic ATLAS 2011 Facsimile: (685) 24675 Email: [email protected] by Website: www.sbs.gov.ws Postal Address: Samoa Bureau of Statistics The Census-Surveys and Demography Division of Samoa Bureau of Statistics (SBS) PO BOX 1151 Apia Samoa National University of Samoa Library CIP entry Samoa socio economic ATLAS 2011 / by The Census-Surveys and Demography Division of Samoa Bureau of Statistics (SBS). -- Apia, Samoa : Samoa Bureau of Statistics, Government of Samoa, 2011. 76 p. : ill. ; 29 cm. Disclaimer: This publication is a product of the Division of Census-Surveys & Demography, ISBN 978 982 9003 66 9 Samoa Bureau of Statistics. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions 1. Census districts – Samoa – maps. 2. Election districts – Samoa – expressed in this volume do not necessarily reflect the views of any funding or census. 3. Election districts – Samoa – statistics. 4. Samoa – census. technical agencies involved in the census. The boundaries and other information I. Census-Surveys and Demography Division of SBS. shown on the maps are only imaginary census boundaries but do not imply any legal status of traditional village and district boundaries. Sam 912.9614 Sam DDC 22. Published by The Samoa Bureau of Statistics, Govt. of Samoa, Apia, Samoa, 2015. Overview Map SAMOA 1 Table of Contents Map 3.4: Tertiary level qualification (Post-secondary certificate, diploma, Overview Map ................................................................................................... 1 degree/higher) by district, 2011 ................................................................... 26 Introduction ...................................................................................................... 3 Map 3.5: Population 15 years and over with knowledge in traditional tattooing by district, 2011 ........................................................................... -

2016 CENSUS Brief No.1

P O BOX 1151 TELEPHONE: (685)62000/21373 LEVEL 1 & 2 FMFM II, Matagialalua FAX No: (685)24675 GOVERNMENT BUILDING Email: [email protected] APIA Website: www.sbs.gov.ws SAMOA 2016 CENSUS Brief No.1 Revised version Population Snapshot and Household Highlights 30th October 2017 1 | P a g e Foreword This publication is the first of a series of Census 2016 Brief reports to be published from the dataset version 1, of the Population and Housing Census, 2016. It provides a snapshot of the information collected from the Population Questionnaire and some highlights of the Housing Questionnaire. It also provides the final count of the population of Samoa in November 7th 2016 by statistical regions, political districts and villages. Over the past censuses, the Samoa Bureau of Statistics has compiled a standard analytical report that users and mainly students find it complex and too technical for their purposes. We have changed our approach in the 2016 census by compiling smaller reports (Census Brief reports) to be released on a quarterly basis with emphasis on different areas of Samoa’s development as well as demands from users. In doing that, we look forward to working more collaboratively with our stakeholders and technical partners in compiling relevant, focused and more user friendly statistical brief reports for planning, policy-making and program interventions. At the same time, the Bureau is giving the public the opportunity to select their own data of interest from the census database for printing rather than the Bureau printing numerous tabulations which mostly remain unused. -

Assessment of Persistent Organic Pollutants in Samoa

POPs Assessment for Samoa Executive Summary Samoa signed the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) in 2001 as part of its national and international commitment to the reduction and elimination of persistent organic and toxic substances. Since signing the Convention, Samoa has received an Enabling Activity Funding from the Global Environment Facility to facilitate the development of its National Implementation Plan (NIP) for POPs. Part of the activities for the development of the NIP includes conducting a National Assessment of POPs produced, imported, used and disposed in Samoa. Furthermore, the National Assessment is to identify the priority chemicals and set objectives for the development of the NIP. From the various studies undertaken on POPs in Samoa, it has been identified that eight of the 12 POPs chemicals identified in the Convention are either produced or imported into the country. Of the eight chemicals, three are pesticides (aldrin, dieldrin, and DDT) used as insecticides for taro and banana plantations and chlordane and heptachlor are used as termiticides in homes. One industrial chemical (PCB) was imported as part of electric transformers while two chemicals (dioxins and furans) are produced and released unintentionally from incomplete combustion. An additionally six POPs and persistent toxic substances (TBT, TPH/PAH, lindane, and CCA/PCP) are also present in Samoa. Of all the chemicals currently present in Samoa only dioxin and furans are still being released from unintentional production while the rest are either non-consented for import or alternatives have been found. All the pesticides and industrial chemicals are no longer imported, with the last known stockpiles disposed by the Agricultural Store in the mid 1990s. -

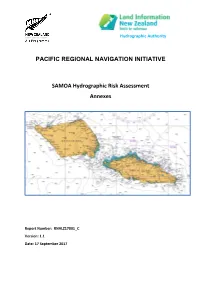

PACIFIC REGIONAL NAVIGATION INITIATIVE SAMOA Hydrographic

Hydrographic Authority PACIFIC REGIONAL NAVIGATION INITIATIVE SAMOA Hydrographic Risk Assessment Annexes Report Number: RNALZ17001_C Version: 1.1 Date: 17 September 2017 SAMOA Hydrographic Risk Assessment _________________________________________________________________________________________ Supported by the New Zealand Aid Programme PACIFIC REGIONAL NAVIGATION INITIATIVE SAMOA Hydrographic Risk Assessment Annexes A joint production by: Land Information New Zealand Level 7 Radio New Zealand House 155 The Terrace Wellington NEW ZEALAND and Rod Nairn & Associates Pty Ltd Hydrographic and Maritime Consultants ABN 50 163 730 58 42 Tamarind Drive Cordeaux Heights NSW AUSTRALIA Authors: Rod Nairn, Michael Beard, Stuart Caie, Ian Harrison, James O’Brien Disclaimer: The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of the New Zealand Government. Satellite AIS data under licence from ORBCOM (augmented by IHS Global Pte Ltd) ii Rod Nairn and Associates Pty Ltd Hydrographic and Maritime Consultants SAMOA Hydrographic Risk Assessment _________________________________________________________________________________________ SAMOA Hydrographic Risk Assessment Annexes A. Event Trees B. GIS Track Creation and Processing C. Traffic Risk Calculation D. Likelihood and Consequence Factors E. Hydrographic Risk Factor Weighting Matrices F. Hydrographic Risk Calculations G. Benefits of Hydrographic Surveys to SAMOA H. List of Consultations References RNA 20170916_C_V1.1 iii SAMOA Hydrographic Risk Assessment _________________________________________________________________________________________