Genome Size Evolution in the Archaea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Genome of Nanoarchaeum Equitans: Insights Into Early Archaeal Evolution and Derived Parasitism

The genome of Nanoarchaeum equitans: Insights into early archaeal evolution and derived parasitism Elizabeth Waters†‡, Michael J. Hohn§, Ivan Ahel¶, David E. Graham††, Mark D. Adams‡‡, Mary Barnstead‡‡, Karen Y. Beeson‡‡, Lisa Bibbs†, Randall Bolanos‡‡, Martin Keller†, Keith Kretz†, Xiaoying Lin‡‡, Eric Mathur†, Jingwei Ni‡‡, Mircea Podar†, Toby Richardson†, Granger G. Sutton‡‡, Melvin Simon†, Dieter So¨ ll¶§§¶¶, Karl O. Stetter†§¶¶, Jay M. Short†, and Michiel Noordewier†¶¶ †Diversa Corporation, 4955 Directors Place, San Diego, CA 92121; ‡Department of Biology, San Diego State University, 5500 Campanile Drive, San Diego, CA 92182; §Lehrstuhl fu¨r Mikrobiologie und Archaeenzentrum, Universita¨t Regensburg, Universita¨tsstrasse 31, D-93053 Regensburg, Germany; ‡‡Celera Genomics Rockville, 45 West Gude Drive, Rockville, MD 20850; Departments of ¶Molecular Biophysics and Biochemistry and §§Chemistry, Yale University, New Haven, CT 06520-8114; and ʈDepartment of Biochemistry, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, VA 24061 Communicated by Carl R. Woese, University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign, Urbana, IL, August 21, 2003 (received for review July 22, 2003) The hyperthermophile Nanoarchaeum equitans is an obligate sym- (6–8). Genomic DNA was either digested with restriction en- biont growing in coculture with the crenarchaeon Ignicoccus. zymes or sheared to provide clonable fragments. Two plasmid Ribosomal protein and rRNA-based phylogenies place its branching libraries were made by subcloning randomly sheared fragments point early in the archaeal lineage, representing the new archaeal of this DNA into a high-copy number vector (Ϸ2.8 kbp library) kingdom Nanoarchaeota. The N. equitans genome (490,885 base or low-copy number vector (Ϸ6.3 kbp library). DNA sequence pairs) encodes the machinery for information processing and was obtained from both ends of plasmid inserts to create repair, but lacks genes for lipid, cofactor, amino acid, or nucleotide ‘‘mate-pairs,’’ pairs of reads from single clones that should be biosyntheses. -

University of Oklahoma Graduate College Development of High

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE DEVELOPMENT OF HIGH-THROUGHPUT EXPERIMENTAL AND COMPUTATIONAL TECHNOLOGIES FOR ANALYZING MICROBIAL FUNCTIONS AND INTERACTIONS IN ENVIRONMENTAL METAGENOMES A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By ZHOU SHI Norman, Oklahoma 2017 DEVELOPMENT OF HIGH-THROUGHPUT EXPERIMENTAL AND COMPUTATIONAL TECHNOLOGIES FOR ANALYZING MICROBIAL FUNCTIONS AND INTERACTIONS IN ENVIRONMENTAL METAGENOMES A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF MICROBIOLOGY AND PLANT BIOLOGY BY ______________________________ Dr. Lee Krumholz, Chair ______________________________ Dr. Meijun Zhu ______________________________ Dr. Sridhar Radhakrishnan ______________________________ Dr. Yiqi Luo ______________________________ Dr. Jizhong Zhou © Copyright by ZHOU SHI 2017 All Rights Reserved. Dedication I dedicate this dissertation to my wife, Mengting Yuan, whom I met and married during the time period of this work and whose love, faith and support is the greatest gift that I can ever imagine in my life; to my son, Andrew Shi, who is always curious, energetic and wonderful, and is my lasting source of enlightenment and true happiness; to my parents, Yiping Shi and Aiping Zeng, whose selfless love and care transcended the distance and time, and carried me whenever I need; to my aunt, Cindy Shi, whose unwavering support and encouragement instilled in me the spirit of striving for excellence; to my friend, Su Xu, who boarded on the same plane with me to the U.S. seven years ago and then has witnessed all parts of this work as my best friend, and Dian Zou, who passed away in an accident during the time period of this work and is a friend I will forever miss. -

Cultivating the Macroalgal Holobiont: Effects of Integrated Multi-Trophic Aquaculture on the Microbiome of Ulva Rigida (Chlorophyta)

fmars-07-00052 February 10, 2020 Time: 15:0 # 1 ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 12 February 2020 doi: 10.3389/fmars.2020.00052 Cultivating the Macroalgal Holobiont: Effects of Integrated Multi-Trophic Aquaculture on the Microbiome of Ulva rigida (Chlorophyta) Gianmaria Califano1, Michiel Kwantes1, Maria Helena Abreu2, Rodrigo Costa3,4,5 and Thomas Wichard1,6* 1 Institute for Inorganic and Analytical Chemistry, Friedrich Schiller University Jena, Jena, Germany, 2 ALGAplus Lda, Ílhavo, Portugal, 3 Institute for Bioengineering and Biosciences, Instituto Superior Técnico, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisbon, Portugal, 4 Centre of Marine Sciences, University of Algarve, Faro, Portugal, 5 Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, U.S. Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute, University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, CA, United States, 6 Jena School for Microbial Communication, Jena, Germany Ulva is a ubiquitous macroalgal genus of commercial interest. Integrated Multi-Trophic Aquaculture (IMTA) systems promise large-scale production of macroalgae due to Edited by: their high productivity and environmental sustainability. Complex host–microbiome Bernardo Antonio Perez Da Gama, interactions play a decisive role in macroalgal development, especially in Ulva spp. Universidade Federal Fluminense, due to algal growth- and morphogenesis-promoting factors released by associated Brazil bacteria. However, our current understanding of the microbial community assembly and Reviewed by: Alejandro H. Buschmann, structure in cultivated macroalgae is scant. We aimed to determine (i) to what extent University of Los Lagos, Chile IMTA settings influence the microbiome associated with U. rigida and its rearing water, (ii) Henrique Fragoso Santos, to explore the dynamics of beneficial microbes to algal growth and development under Universidade Federal Fluminense, Brazil IMTA settings, and (iii) to improve current knowledge of host–microbiome interactions. -

Insights Into Archaeal Evolution and Symbiosis from the Genomes of a Nanoarchaeon and Its Inferred Crenarchaeal Host from Obsidian Pool, Yellowstone National Park

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Microbiology Publications and Other Works Microbiology 4-22-2013 Insights into archaeal evolution and symbiosis from the genomes of a nanoarchaeon and its inferred crenarchaeal host from Obsidian Pool, Yellowstone National Park Mircea Podar University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Kira S. Makarova National Institutes of Health David E. Graham University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Yuri I. Wolf National Institutes of Health Eugene V. Koonin National Institutes of Health See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_micrpubs Part of the Microbiology Commons Recommended Citation Biology Direct 2013, 8:9 doi:10.1186/1745-6150-8-9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Microbiology at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Microbiology Publications and Other Works by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Mircea Podar, Kira S. Makarova, David E. Graham, Yuri I. Wolf, Eugene V. Koonin, and Anna-Louise Reysenbach This article is available at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange: https://trace.tennessee.edu/ utk_micrpubs/44 Podar et al. Biology Direct 2013, 8:9 http://www.biology-direct.com/content/8/1/9 RESEARCH Open Access Insights into archaeal evolution and symbiosis from the genomes of a nanoarchaeon and its inferred crenarchaeal host from Obsidian Pool, Yellowstone National Park Mircea Podar1,2*, Kira S Makarova3, David E Graham1,2, Yuri I Wolf3, Eugene V Koonin3 and Anna-Louise Reysenbach4 Abstract Background: A single cultured marine organism, Nanoarchaeum equitans, represents the Nanoarchaeota branch of symbiotic Archaea, with a highly reduced genome and unusual features such as multiple split genes. -

Genome Size Evolution in the Archaea

Kellner, S., Spang, A., Offre, P., Szollosi, G. J., Petitjean, C., & Williams, T. (2018). Genome size evolution in the Archaea. Emerging Topics in Life Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1042/ETLS20180021 Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record License (if available): CC BY Link to published version (if available): 10.1042/ETLS20180021 Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document This is the final published version of the article (version of record). It first appeared online via Portland Press at http://www.emergtoplifesci.org/content/early/2018/11/13/ETLS20180021 . Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ Emerging Topics in Life Sciences (2018) https://doi.org/10.1042/ETLS20180021 Review Article Genome size evolution in the Archaea Siri Kellner1, Anja Spang2,3, Pierre Offre2, Gergely J. Szöllo˝si4,5, Celine Petitjean6 and Tom A. Williams6 1School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, Bristol BS8 1TQ, U.K.; 2NIOZ, Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research, Department of Marine Microbiology and Biogeochemistry, and Utrecht University, P.O. Box 59, NL-1790 AB Den Burg, The Netherlands; 3Department of Cell and Molecular Biology, Science for Life Laboratory, Uppsala University, SE-75123, Uppsala, Sweden; 4MTA-ELTE Lendület Evolutionary Genomics Research Group, 1117 Budapest, Hungary; 5Department of Biological Physics, Eötvös Loránd University, 1117 Budapest, Hungary; 6School of Biological Sciences, University of Bristol, Bristol BS8 1TQ, U.K. -

Emended Descriptions of Genera of the Family Halobacteriaceae

International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology (2009), 59, 637–642 DOI 10.1099/ijs.0.008904-0 Taxonomic Emended descriptions of genera of the family Note Halobacteriaceae Aharon Oren,1 David R. Arahal2 and Antonio Ventosa3 Correspondence 1Institute of Life Sciences, and the Moshe Shilo Minerva Center for Marine Biogeochemistry, Aharon Oren The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Jerusalem 91904, Israel [email protected] 2Departamento de Microbiologı´a y Ecologı´a and Coleccio´n Espan˜ola de Cultivos Tipo (CECT), Universidad de Valencia, 46100 Burjassot, Valencia, Spain 3Department of Microbiology and Parasitology, Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Sevilla, 41012 Sevilla, Spain The family Halobacteriaceae currently contains 96 species whose names have been validly published, classified in 27 genera (as of September 2008). In recent years, many novel species have been added to the established genera but, in many cases, one or more properties of the novel species do not agree with the published descriptions of the genera. Authors have often failed to provide emended genus descriptions when necessary. Following discussions of the International Committee on Systematics of Prokaryotes Subcommittee on the Taxonomy of Halobacteriaceae, we here propose emended descriptions of the genera Halobacterium, Haloarcula, Halococcus, Haloferax, Halorubrum, Haloterrigena, Natrialba, Halobiforma and Natronorubrum. The family Halobacteriaceae was established by Gibbons rRNA gene sequence-based phylogenetic trees rather than (1974) to accommodate the genera Halobacterium and on true polyphasic taxonomy such as recommended for the Halococcus. At the time of writing (September 2008), the family (Oren et al., 1997). As a result, there are often few, if family contained 96 species whose names have been validly any, phenotypic properties that enable the discrimination published, classified in 27 genera. -

Archaea and the Origin of Eukaryotes

REVIEWS Archaea and the origin of eukaryotes Laura Eme, Anja Spang, Jonathan Lombard, Courtney W. Stairs and Thijs J. G. Ettema Abstract | Woese and Fox’s 1977 paper on the discovery of the Archaea triggered a revolution in the field of evolutionary biology by showing that life was divided into not only prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Rather, they revealed that prokaryotes comprise two distinct types of organisms, the Bacteria and the Archaea. In subsequent years, molecular phylogenetic analyses indicated that eukaryotes and the Archaea represent sister groups in the tree of life. During the genomic era, it became evident that eukaryotic cells possess a mixture of archaeal and bacterial features in addition to eukaryotic-specific features. Although it has been generally accepted for some time that mitochondria descend from endosymbiotic alphaproteobacteria, the precise evolutionary relationship between eukaryotes and archaea has continued to be a subject of debate. In this Review, we outline a brief history of the changing shape of the tree of life and examine how the recent discovery of a myriad of diverse archaeal lineages has changed our understanding of the evolutionary relationships between the three domains of life and the origin of eukaryotes. Furthermore, we revisit central questions regarding the process of eukaryogenesis and discuss what can currently be inferred about the evolutionary transition from the first to the last eukaryotic common ancestor. Sister groups Two descendants that split The pioneering work by Carl Woese and colleagues In this Review, we discuss how culture- independent from the same node; the revealed that all cellular life could be divided into three genomics has transformed our understanding of descendants are each other’s major evolutionary lines (also called domains): the archaeal diversity and how this has influenced our closest relative. -

Pan-Genome Analysis and Ancestral State Reconstruction Of

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Pan‑genome analysis and ancestral state reconstruction of class halobacteria: probability of a new super‑order Sonam Gaba1,2, Abha Kumari2, Marnix Medema 3 & Rajeev Kaushik1* Halobacteria, a class of Euryarchaeota are extremely halophilic archaea that can adapt to a wide range of salt concentration generally from 10% NaCl to saturated salt concentration of 32% NaCl. It consists of the orders: Halobacteriales, Haloferaciales and Natriabales. Pan‑genome analysis of class Halobacteria was done to explore the core (300) and variable components (Softcore: 998, Cloud:36531, Shell:11784). The core component revealed genes of replication, transcription, translation and repair, whereas the variable component had a major portion of environmental information processing. The pan‑gene matrix was mapped onto the core‑gene tree to fnd the ancestral (44.8%) and derived genes (55.1%) of the Last Common Ancestor of Halobacteria. A High percentage of derived genes along with presence of transformation and conjugation genes indicate the occurrence of horizontal gene transfer during the evolution of Halobacteria. A Core and pan‑gene tree were also constructed to infer a phylogeny which implicated on the new super‑order comprising of Natrialbales and Halobacteriales. Halobacteria1,2 is a class of phylum Euryarchaeota3 consisting of extremely halophilic archaea found till date and contains three orders namely Halobacteriales4,5 Haloferacales5 and Natrialbales5. Tese microorganisms are able to dwell at wide range of salt concentration generally from 10% NaCl to saturated salt concentration of 32% NaCl6. Halobacteria, as the name suggests were once considered a part of a domain "Bacteria" but with the discovery of the third domain "Archaea" by Carl Woese et al.7, it became part of Archaea. -

The Role of Stress Proteins in Haloarchaea and Their Adaptive Response to Environmental Shifts

biomolecules Review The Role of Stress Proteins in Haloarchaea and Their Adaptive Response to Environmental Shifts Laura Matarredona ,Mónica Camacho, Basilio Zafrilla , María-José Bonete and Julia Esclapez * Agrochemistry and Biochemistry Department, Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Area, Faculty of Science, University of Alicante, Ap 99, 03080 Alicante, Spain; [email protected] (L.M.); [email protected] (M.C.); [email protected] (B.Z.); [email protected] (M.-J.B.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-965-903-880 Received: 31 July 2020; Accepted: 24 September 2020; Published: 29 September 2020 Abstract: Over the years, in order to survive in their natural environment, microbial communities have acquired adaptations to nonoptimal growth conditions. These shifts are usually related to stress conditions such as low/high solar radiation, extreme temperatures, oxidative stress, pH variations, changes in salinity, or a high concentration of heavy metals. In addition, climate change is resulting in these stress conditions becoming more significant due to the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events. The most relevant damaging effect of these stressors is protein denaturation. To cope with this effect, organisms have developed different mechanisms, wherein the stress genes play an important role in deciding which of them survive. Each organism has different responses that involve the activation of many genes and molecules as well as downregulation of other genes and pathways. Focused on salinity stress, the archaeal domain encompasses the most significant extremophiles living in high-salinity environments. To have the capacity to withstand this high salinity without losing protein structure and function, the microorganisms have distinct adaptations. -

1 Characterization of Sulfur Metabolizing Microbes in a Cold Saline Microbial Mat of the Canadian High Arctic Raven Comery Mast

Characterization of sulfur metabolizing microbes in a cold saline microbial mat of the Canadian High Arctic Raven Comery Master of Science Department of Natural Resource Sciences Unit: Microbiology McGill University, Montreal July 2015 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master in Science © Raven Comery 2015 1 Abstract/Résumé The Gypsum Hill (GH) spring system is located on Axel Heiberg Island of the High Arctic, perennially discharging cold hypersaline water rich in sulfur compounds. Microbial mats are found adjacent to channels of the GH springs. This thesis is the first detailed analysis of the Gypsum Hill spring microbial mats and their microbial diversity. Physicochemical analyses of the water saturating the GH spring microbial mat show that in summer it is cold (9°C), hypersaline (5.6%), and contains sulfide (0-10 ppm) and thiosulfate (>50 ppm). Pyrosequencing analyses were carried out on both 16S rRNA transcripts (i.e. cDNA) and genes (i.e. DNA) to investigate the mat’s community composition, diversity, and putatively active members. In order to investigate the sulfate reducing community in detail, the sulfite reductase gene and its transcript were also sequenced. Finally, enrichment cultures for sulfate/sulfur reducing bacteria were set up and monitored for sulfide production at cold temperatures. Overall, sulfur metabolism was found to be an important component of the GH microbial mat system, particularly the active fraction, as 49% of DNA and 77% of cDNA from bacterial 16S rRNA gene libraries were classified as taxa capable of the reduction or oxidation of sulfur compounds. -

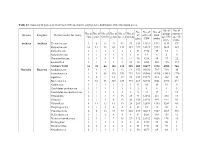

Domain Kingdom Phylum (Order for Virus) No. of Class No. of Order No. of Family No. of Genus No. of Species No. of Strains No. O

Table S2. Summary of probes on GeoChip 5.0M based on the phylogenetic distribution of the functional genes. No. of No. of No. No. of No. of No. of No. of No. of No. of No. of No. of group- sequence Domain Kingdom Phylum (order for virus) of covered total class order family genus species strains specific -specific gene CDS probe probe probe Archaea Archaea Crenarchaeota 2 6 9 22 43 57 142 13921 1312 1133 179 Euryarchaeota 10 12 23 69 133 187 229 33323 3992 3625 367 Korarchaeota 1 1 1 1 1 1 33 3718 35 33 2 Nanoarchaeota 1 1 1 1 1 1 6 12 6 6 0 Thaumarchaeota 1 4 5 7 9 14 46 5218 95 73 22 unclassified 1 1 1 1 1 25 46 1885 288 115 173 Archaea Total 16 25 40 101 188 285 502 58077 5728 4985 743 Bacteria Bacteria Acidobacteria 5 4 4 8 13 18 155 20180 745 715 30 Actinobacteria 1 8 48 120 351 753 381 80060 15394 13618 1776 Aquificae 1 2 4 12 17 22 127 19379 533 498 35 Bacteroidetes 7 10 23 107 239 394 267 58970 9661 8790 871 Caldiserica 1 1 1 1 1 1 13 38 19 19 0 Candidatus poribacteria 1 1 1 1 1 1 2 5 4 1 3 Candidatus saccharibacteria 1 1 1 1 1 3 9 22 17 4 13 Chlamydiae 2 1 4 7 15 23 74 12652 241 230 11 Chlorobi 1 1 1 6 15 20 138 21932 995 944 51 Chloroflexi 8 11 12 14 19 28 209 32839 1353 1289 64 Chrysiogenetes 1 1 1 2 2 2 33 81 41 40 1 Cyanobacteria 2 8 12 57 97 203 237 46219 4727 4209 518 Deferribacteres 1 1 1 4 4 4 81 2583 165 154 11 Deinococcus-thermus 2 3 4 7 18 27 172 21352 1026 978 48 Dictyoglomi 1 1 1 1 2 2 51 9447 99 98 1 Elusimicrobia 2 2 2 2 2 2 34 5713 50 49 1 Fibrobacteres 2 1 1 1 1 2 50 6671 69 64 5 Firmicutes 6 10 42 176 593 1556 -

Concerted Gene Recruitment in Early Plant Evolution Jinling Huang* and J Peter Gogarten†

Open Access Research2008HuangVolume and 9, Issue Gogarten 7, Article R109 Concerted gene recruitment in early plant evolution Jinling Huang* and J Peter Gogarten† Addresses: *Department of Biology, Howell Science Complex, East Carolina University, Greenville, NC 27858, USA. †Department of Molecular and Cell Biology, University of Connecticut, 91 North Eagleville Road, Storrs, CT 06269, USA. Correspondence: Jinling Huang. Email: [email protected] Published: 8 July 2008 Received: 30 April 2008 Revised: 24 June 2008 Genome Biology 2008, 9:R109 (doi:10.1186/gb-2008-9-7-r109) Accepted: 8 July 2008 The electronic version of this article is the complete one and can be found online at http://genomebiology.com/2008/9/7/R109 © 2008 Huang and Gogarten; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Eukaryotic<p>Analysesto the split ofhorizontal ofred the algae red gene andalgal transfergreen <it>Cyanidioschyzon</it> plants.</p> genome identified 37 genes that were acquired from non-organellar sources prior Abstract Background: Horizontal gene transfer occurs frequently in prokaryotes and unicellular eukaryotes. Anciently acquired genes, if retained among descendants, might significantly affect the long-term evolution of the recipient lineage. However, no systematic studies on the scope of anciently acquired genes and their impact on macroevolution are currently available in eukaryotes. Results: Analyses of the genome of the red alga Cyanidioschyzon identified 37 genes that were acquired from non-organellar sources prior to the split of red algae and green plants.