Orphan Black"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Discrimination Against Men Appearance and Causes in the Context of a Modern Welfare State

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Lauda Pasi Malmi Discrimination Against Men Appearance and Causes in the Context of a Modern Welfare State Academic Dissertation to be publicly defended under permission of the Faculty of Social Sciences at the University of Lapland in the Mauri Hall on Friday 6th of February 2009 at 12 Acta Electronica Universitatis Lapponiensis 39 University of Lapland Faculty of Social Sciences Copyright: Pasi Malmi Distributor: Lapland University Press P.O. Box 8123 FI-96101 Rovaniemi tel. + 358 40-821 4242 , fax + 358 16 341 2933 publication@ulapland.fi www.ulapland.fi /publications Paperback ISBN 978-952-484-279-2 ISSN 0788-7604 PDF ISBN 978-952-484-309-6 ISSN 1796-6310 www.ulapland.fi /unipub/actanet 3 Abstract Malmi Pasi Discrimination against Men: Appearance and Causes in the Context of a Modern Welfare State Rovaniemi: University of Lapland, 2009, 453 pp., Acta Universitatis Lapponinsis 157 Dissertation: University of Lapland ISSN 0788-7604 ISBN 978-952-484-279-2 The purpose of the work is to examine the forms of discrimination against men in Finland in a manner that brings light also to the appearance of this phenomenon in other welfare states. The second goal of the study is to create a model of the causes of discrimination against men. According to the model, which synthesizes administrative sciences, gender studies and memetics, gender discrimination is caused by a mental diff erentiation between men and women. This diff erentiation tends to lead to the segregation of societies into masculine and feminine activities, and to organizations and net- works which are dominated by either men or by women. -

English Department Course Descriptions Spring 2017 Macomb

English Department Course Descriptions Spring 2017 Macomb Campus Undergraduate Courses English Literature & Writing ENG 200 Introduction to Poetry Section 1 – Merrill Cole Aim: Marianne Moore’s famous poem, “Poetry,” begins, “I too dislike it.” Certainly many people would agree, not considering that their favorite rap or song lyric is poetry, or perhaps forgetting the healing words spoken at a grandparent’s funeral. We often turn to poetry when something happens in our lives that needs special expression, such as when we fall in love or want to speak at a public event. It is true that poems can be difficult, but they can also ring easy and true. Poems may cause us to think hard, or make us feel something deeply. This course offers a broad introduction to poetry, across time and around the globe. The emphasis falls, though, on contemporary poetry more relevant to our everyday concerns. For most of the semester, the readings are organized around formal topics, such as imagery, irony, and free verse. The course also attends to traditional verse forms, which are not only still in use, but also help us better to understand contemporary poetry. Toward the end of the semester, we shift focus to look at two important books of poetry, Frank O’Hara’s 1964 Lunch Poems and Kim Addonizio’s 2000 Tell Me. Although Marianne Moore recognizes that many people “dislike” poetry, she insists that “one discovers in / it after all, a place for the genuine.” William Carlos Williams concurs: ‘ Look at what passes for the new. You will not find it there but in despised poems. -

American Odyssey,' 'Last Ship,' 'Orphan Black' and More on Day 2 of Wonder-Con

'American Odyssey,' 'Last Ship,' 'Orphan Black' and more on Day 2 of Wonder-Con 04.05.2015 Day 2 of WonderCon 2015 has arrived and with it comes oodles of panels for shows about to premiere. The Last Ship (TNT) TNT joined the fray on Saturday, with banners advertising the second season of the show, as well as brand new "R U Immune 2?" t-shirts for those that attended the show's panel. TNT also released a season-two trailer on Friday. The Last Ship premieres June 28 at 9/8 c. The Messengers (CW) In Attendance: creator Eoghan O'Donnell; Executive Producer Trey Callaway; stars Jon Fletcher, Shantel VanSanten, Craig Frank, Diogo Morgado, Anna Diop, Joel Courtney and J.D. Pardo. CW's newest genre show certainly has a high concept: five different characters are given gifts and are tasked with the responsibility to prevent the end of days on Earth. Given the Easter weekend background and the appearance of angels and a Devil-like character in its pilot, it's easy to see the show's religious themes. But, Trey Callaway explains, "it's not a show about religion. It's a show about faith." Shantel VanSanten continues, "it's not about a specific faith or message, it's about coming together." This is a theme Callaway hopes can be explored "over many seasons." While The Messengers is about hope, that's not the show's main priority. "I'm a big sucker for a rollercoaster. Our first job is to entertain in a way a rollercoaster does. -

A Critical Analysis of American Horror Story: Coven

Volume 5 ׀ Render: The Carleton Graduate Journal of Art and Culture Witches, Bitches, and White Feminism: A Critical Analysis of American Horror Story: Coven By Meg Lonergan, PhD Student, Law and Legal Studies, Carleton University American Horror Story: Coven (2013) is the third season an attempt to tell a better story—one that pushes us to imag- analysis thus varies from standard content analysis as it allows of the popular horror anthology on FX1. Set in post-Hurricane ine a better future. for a deeper engagement and understanding of the text, the Katrina New Orleans, Louisiana, the plot centers on Miss Ro- symbols and meaning within the text, and theoretical relation- This paper combines ethnographic content analysis bichaux’s Academy and its new class of female students— ships with other texts and socio-political realities. This method and intersectional feminist analysis to engage with the televi- witches descended from the survivors of the witch trials in Sa- is particularly useful for allowing the researcher deep involve- sion show American Horror Story: Coven (2013) to conduct a lem, Massachusetts in 16922. The all-girls school is supposed ment with the text to develop a descriptive account of the com- close textual reading of the show and unpack how the repre- to be a haven for witches to learn about their heritage and plexities of the narrative (Ferrell et al. 2008, 189). In closely sentations of a diversity of witches can be read and under- powers while fostering a community which protects them from examining the text (Coven) to explore the themes and relation- stood as representing a diversity of types of feminism. -

The Divergent Archive and Androcentric Counterpublics: Public Rhetorics, Memory, and Archives

THE DIVERGENT ARCHIVE AND ANDROCENTRIC COUNTERPUBLICS: PUBLIC RHETORICS, MEMORY, AND ARCHIVES BY EVIN SCOTT GROUNDWATER DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2020 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Kelly Ritter, Chair Associate Professor Peter Mortensen Assistant Professor John Gallagher Associate Professor Jessica Enoch, University of Maryland ii ABSTRACT As a field, Writing Studies has long been concerned with the rhetorical representation of both dominant and marginalized groups. However, rhetorical theory on publics and counterpublics tends not to articulate how groups persuade others of their status as mainstream or marginal. Scholars of public/counterpublic theory have not yet adequately examined the mechanisms through which rhetorical resources play a role in reinforcing and/or dispelling public perceptions of dominance or marginalization. My dissertation argues many counterpublics locate and convince others of their subject status through the development of rhetorical resources. I contend counterpublics create and curate a diffuse system of archives, which I refer to as “divergent archives.” These divergent archives often lack institutional backing, rigor, and may be primarily composed of ephemera. Drawing from a variety of archival materials both within and outside institutionally maintained archives, I explore how counterpublics perceiving themselves as marginalized construct archives of their own as a way to transmit collective memories reifying their nondominant status. I do so through a case study that has generally been overlooked in Writing Studies: a collection of men’s rights movements which imagine themselves to be marginalized, despite their generally hegemonic positions. -

Burning Woman Pdf Free Download

BURNING WOMAN PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Lucy H. Pearce | 282 pages | 22 May 2016 | Womancraft Publishing | 9781910559161 | English | Ireland Burning Woman PDF Book If you buy through links on this page, we may earn a small commission. Copyright KSLA. Read this again. I have actually finished this book but still pick it up from time to time to re-read the odd chapter that resonates with where I am in my personal journey right now. Chlamydia, genital herpes, and trichomoniasis are all linked with preterm delivery. May 05, Adva rated it liked it. Aleyamma Mathew was a registered nurse at a hospital in Carrollton, Texas , who died of burn wounds on 5 April Welcome back. The life force. Patch testing using the suspected allergen to stimulate a controlled reaction in a clinical setting can help to identify which substance is creating the burning sensation. Just a moment while we sign you in to your Goodreads account. The reason, It was thought inducing. Preview — Burning Woman by Lucy H. Finally, some scholars argue that the dowry practice came out of British rule and influence in India to distinguish "different forms of marriage" between castes. I realised I coulst and to lose everything - my reputation, my community, my beloved husband, my precious children - simply for doing the work that I burn to do. If you say that women are being abused by marketing companies and the media then I guess you've never seen a Calvin Klein or your usual deodorant ad Then it is up to you to decide if you will answer. -

Short-Term Fate of Rehabilitated Orphan Black Bears Released in New Hampshire

Human–Wildlife Interactions 10(2): 258–267, Fall 2016 Short-term fate of rehabilitated orphan black bears released in New Hampshire Wˎ˜˕ˎˢ E. S˖˒˝ˑ1, Department of Natural Resources and the Environment, University of New Hampshire, 56 College Road, Durham, NH 03824, USA [email protected] Pˎ˝ˎ˛ J. Pˎ˔˒˗˜, Department of Natural Resources and the Environment, University of New Hampshire, 56 College Road, Durham, NH 03824, USA A˗ˍ˛ˎˠ A. T˒˖˖˒˗˜, New Hampshire Fish and Game Department, 629B Main Street, Lancaster, NH 03584, USA Bˎ˗˓ˊ˖˒˗ K˒˕ˑˊ˖, P.O. Box 37, Lyme, NH 03768, USA Abstract: We evaluated the release of rehabilitated, orphan black bears (Ursus americanus) in northern New Hampshire. Eleven bears (9 males, 2 females; 40–45 kg) were outfi tted with GPS radio-collars and released during May and June of 2011 and 2012. Bears released in 2011 had higher apparent survival and were not observed or reported in any nuisance behavior, whereas no bears released in 2012 survived, and all were involved in minor nuisance behavior. Analysis of GPS locations indicated that bears in 2011 had access to and used abundant natural forages or habitat. Conversely, abundance of soft and hard mast was lower in 2012, suggesting that nuisance behavior, and consequently survival, was inversely related to availability of natural forage. Dispersal from the release site ranged from 3.4–73 km across both years, and no bear returned to the rehabilitation facility (117 km distance). Rehabilitation appears to be a valid method for addressing certain orphan bear issues in New Hampshire. -

Metaphors of Patriarchy in Orphan Black and Westworld

Feminist Media Studies ISSN: 1468-0777 (Print) 1471-5902 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rfms20 Metaphors of patriarchy in Orphan Black and Westworld Olivia Belton To cite this article: Olivia Belton (2020): Metaphors of patriarchy in OrphanBlack and Westworld, Feminist Media Studies, DOI: 10.1080/14680777.2019.1707701 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2019.1707701 Published online: 21 Jan 2020. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 70 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rfms20 FEMINIST MEDIA STUDIES https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2019.1707701 Metaphors of patriarchy in Orphan Black and Westworld Olivia Belton Leverhulme Centre for the Future of Intelligence, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY Orphan Black (2013–17) and Westworld (2016-) use their science Received 7 August 2018 fiction narratives to create metaphors for patriarchal oppression. Revised 12 November 2019 The female protagonists struggle against the paternalistic scientists Accepted 18 December 2019 and corporate leaders who seek to control them. These series break KEYWORDS away from more liberal representations of feminism on television Science fiction; television; by explicitly portraying how systemic patriarchal oppression seeks patriarchy; cyborgs; to control and exploit women, especially under capitalism. They feminism also engage with radical feminist ideas of separatism and compul- sory heterosexuality. The science fiction plots allow them to deal with feminist issues. Westworld uses computer programming as a metaphor for patriarchal social conditioning, while Orphan Black’s clones recall cyborg feminism. -

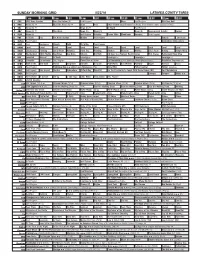

Sunday Morning Grid 5/22/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 5/22/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Boss Paid Program PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Paid 2016 French Open Tennis First Round. From Roland Garros Stadium in Paris. 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News (N) Supervisorial Debate Explore 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program FabLab I Love Lucy 13 MyNet Paid Program Somewhere Slow (2013) 18 KSCI Paid Hormones Church Faith Dr. Willar Paid Program 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Landscapes Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexican Martha Ellie’s Real Baking Simply Ming 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Bug Bites Bug Bites Edisons Biz Kid$ 30 Days to a Younger Heart-Masley Rick Steves Retirement Road Map 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Paid Program Como Dice el Dicho La Comadrita (1978, Comedia) María Elena Velasco. República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Schuller In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Firehouse Dog ›› (2007) Josh Hutcherson. -

The List: All Primetime Series on Television Calendar Year 2015

The List: All Primetime Series on Television Calendar Year 2015 Source: Nielsen, Live+7 data provided by FX Networks Research. 12/29/14-12/27/15. Original telecasts only. Excludes repeats, specials, movies, news, sports, programs with only one telecast, and Spanish language nets. Cable: Mon-Sun, 8-11P. Broadcast: Mon-Sat, 8-11P; Sun 7-11P. "<<" denotes below Nielsen minimum reporting standards based on P2+ Total U.S. Rating to the tenth (0.0). Important to Note: This list utilizes the TV Guide listing service to denote original telecasts (and exclude repeats and specials), and also line-items original series by the internal coding/titling provided to Nielsen by each network. Thus, if a network creates different "line items" to denote different seasons or different day/time periods of the same series within the calendar year, both entries are listed separately. The following provides examples of separate line items that we counted as one show: %(7 V%HLQJ0DU\-DQH%(,1*0$5<-$1(6DQG%(,1*0$5<-$1(6 1%& V7KH9RLFH92,&(DQG92,&(78( 1%& V7KH&DUPLFKDHO6KRZ&$50,&+$(/6+2:3DQG&$50,&+$(/6+2: Again, this is a function of how each network chooses to manage their schedule. Hence, we reference this as a list as opposed to a ranker. Based on our estimated manual count, the number of unique series are: 2015³1,415 primetime series (1,524 line items listed in the file). 2014³1,517 primetime series (1,729 line items). The List: All Primetime Series on Television Calendar Year 2015 Source: Nielsen, Live+7 data provided by FX Networks Research. -

Responding to Misogyny, Reciprocating Hate Speech - South Korea's Online Feminism Movement: Megalia

Responding to Misogyny, Reciprocating Hate Speech - South Korea's Online Feminism Movement: Megalia The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Lee, Wonyun. 2019. Responding to Misogyny, Reciprocating Hate Speech - South Korea's Online Feminism Movement: Megalia. Master's thesis, Harvard Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. Citable link https://nrs.harvard.edu/URN-3:HUL.INSTREPOS:37366046 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Author Responding to Misogyny, Reciprocating Hate Speech South Korea’s Online Feminism Movement: Megalia A Thesis in the Field of Anthropology for the Degree of Master of Arts Harvard University November 2019 Copyright 2019 [Wonyun Lee] Acknowledgements The year in Harvard for me had been an incredibly rewarding experience. Looking back, I cannot believe how much I have learned and grown. This is, for the most part, thanks to my two advisors: Pr. Arthur Kleinman and Pr. Byron Good. I learned so much from them. I have the greatest respect for Arthur Kleinman for his academic rigorousness. His classes were intellectually insightful and resolute with political engagement. His commitment to academic integrity taught me to become a better anthropologist. I express my deepest gratitude to Byron Good, for his classes as well as many hours of our personal conversations. His penetrating wisdom shaped and refined my thesis. -

2015 Summer Reading

WCU ENGLISH DEPARTMENT SUMMER READING & VIEWING LIST: Faculty Picks 2015 This annual list presents suggestions for summer reading/viewing from individual faculty of the West Chester University English Department. You can also find this list & its predecessors at http://www.wcupa.edu/_academics/sch_cas.eng/facultyPicks.aspx. Book, podcast, film, site: Recommender: 20 Feet From Stardom Maureen McVeigh Trainor Morgan Neville, Director They sing your favorite songs, but you’ve probably never heard of them. This film highlights the backup singers of some of the most iconic American bands and the stark contrast of their lives to those of the famous musicians. Exploring ideas of gender, race, and economics, this film is engaging, thought-provoking, and entertaining, just like the music it includes. I saw this movie on a whim and have been recommending it ever since. It won an Oscar for Best Documentary and is available on Netflix. And, fellow faculty, because of this film, I learned we all have something in common with the woman who inspired the song Brown Sugar as she is now an adjunct professor of languages. 99% Invisible Rodney Mader http://99percentinvisible.org The title comes from a quotation by Buckminster Fuller about the unseen centrality of design to human lives: "Ninety-nine percent of who you are is invisible and untouchable.” A favorite of Ira Glass and the Radiolab team, the production values are excellent, and the stories are cocktail party gold. Recent shows cover the popularity of the Portland airport’s carpet design; the introduction of palm trees to Los Angeles; an electric bulb that has been continuously operating for 113 years; and how you can always tell what used to be a Pizza Hut.