Spring 2004 Issue 12

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Christian Divination in Late Antiquity Late in Divination Christian

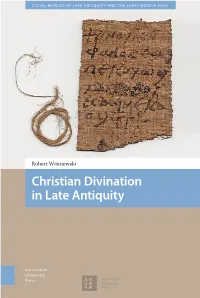

EASTERNSOCIAL WORLDS EUROPEAN OF LATE SCREEN ANTIQUITY CULTURES AND THE EARLY MIDDLE AGES Wiśniewski Christian Divination in Late Antiquity Robert Wiśniewski Christian Divination in Late Antiquity Christian Divination in Late Antiquity Social Worlds of Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages The Late Antiquity experienced profound cultural and social change: the political disintegration of the Roman Empire in the West, contrasted by its continuation and transformation in the East; the arrival of ‘barbarian’ newcomers and the establishment of new polities; a renewed militarization and Christianization of society; as well as crucial changes in Judaism and Christianity, together with the emergence of Islam and the end of classical paganism. This series focuses on the resulting diversity within Late Antique society, emphasizing cultural connections and exchanges; questions of unity and inclusion, alienation and conflict; and the processes of syncretism and change. By drawing upon a number of disciplines and approaches, this series sheds light on the cultural and social history of Late Antiquity and the greater Mediterranean world. Series Editor Carlos Machado, University of St. Andrews Editorial Board Lisa Bailey, University of Auckland Maijastina Kahlos, University of Helsinki Volker Menze, Central European University Ellen Swift, University of Kent Enrico Zanini, University of Siena Christian Divination in Late Antiquity Robert Wiśniewski Translated by Damian Jasiński Amsterdam University Press The translation of the text for this book was funded by a grant from the National Programme for the Development of the Humanities (Poland) project 21H 18 0098 86. Cover illustration: Oracular ticket from Antinoë discovered on 21 October 1984 at the East Kom (sector D 2 III) and published by Alain Delattre (2017). -

Download File

0 THE SORCERER’S SECRETS Strategies to Practical Magick By JASON MILLER NEW PAGE BOOKS A division of The Career Press, Inc. Franklin Lakes, NJ Copyright © 2009 by Jason Miller All rights reserved under the Pan-American and International Copyright Conventions. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system now known or hereafter invented, without written permission from the publisher, The Career Press. Artwork courtesy of Matthew Brownlee. TTTHEHEHE SORCERERORCERERORCERER’’’SSS SECRETSECRETSECRETS EDITED BY KATE HENCHES TYPESET BY EILEEN MUNSON Cover design by Ian Shimkoviak, the Book Designers Printed in the U.S.A. by Book-mart Press To order this title, please call toll-free 1-800-CAREER-1 (NJ and Canada: 201-848- 0310) to order using VISA or MasterCard, or for further information on books from Career Press. The Career Press, Inc., 3 Tice Road, PO Box 687, Franklin Lakes, NJ 07417 www.careerpress.com www.newpagebooks.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Miller, Jason, 1972– The sorcerer’s secrets : strategies to practical magick / by Jason Miller. p. cm. Includes index. 1. Magic. 2. Incantations. I. Title. BF1621.M56 2009 133.4’3--dc22 2008054313 0 This work is dedicated to the memory of James W. Flemming, 1974–2008. This page intentionally left blank 0 Acknowledgments irst and foremost, I wish to thank my wife for her patience and Fencouragement during the writing of this book. Thanks also to my mother and father for raising me in an environment that was conductive to learning the magickal arts, and for always encouraging me in my esoteric pursuits, no matter how strange they seemed or how far away they took me. -

3161528603 Lp.Pdf

Studien und Texte zu Antike und Christentum Studies and Texts in Antiquity and Christianity Herausgeber/Editors Christoph Markschies (Berlin) Martin Wallraff (Basel) Christian Wildberg (Princeton) Beirat/Advisory Board Peter Brown (Princeton) · Susanna Elm (Berkeley) Johannes Hahn (Münster) · Emanuela Prinzivalli (Rom) Jörg Rüpke (Erfurt) 89 AnneMarie Luijendijk Forbidden Oracles? The Gospel of the Lots of Mary Mohr Siebeck AnneMarie Luijendijk, 1996 Th.M. from the Vrije Universiteit in Amsterdam; 2005 Th.D. from Harvard University; 2006–12 Assistant Professor of Religion at Princeton University; since 2012 Associate Professor of Religion at Princeton University. e-ISBN PDF 978-3-16-152860-6 ISBN 978-3-16-152859-0 ISSN 1436-3003 (Studien und Texte zu Antike und Christentum) Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliographie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2014 by Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen, Germany. www.mohr.de This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that permitted by copyright law) without the publisher’s written permission. This applies particularly to reproduc- tions, translations, microfilms and storage and processing in electronic systems. The book was typeset by Laupp & Göbel in Nehren using Times New Roman, IFAO Greek and IFAO Coptic typeface, print ed on non-aging paper and bound by Buchbinderei Nädele in Nehren. Printed in Germany. Dedicated to my children Kees, Erik, Rosemarie and Annabel with love. Preface This book centers on The Gospel of the Lots of Mary, a previously unknown text pre- served in a fifth- or sixth-century Coptic miniature codex. -

Die Lot Kroniek

Die Lot Kroniek J.G. Erasmus 33/53 AOV - Spreuke 16:33 “In die skoot word die lot gewerp, maar elke beslissing daarvan kom van die HERE.” LOT KRONIEK KRONOLOGIESE GESKIEDENIS OOR DIE GEBRUIK VAN DIE LOT VANUIT DIE BYBELSE TYD TOT VANDAG IN SUID-AFRIKA Laai gerus die Lot Kroniek elektronies af, of skakel ons insake vrae, voorstelle of seminare @ Webtuiste: www.lotkroniek.co.za Elektroniese posadres: [email protected] DAAR IS GEEN KOPIEREG OP HIERDIE BOEK NIE. 2014-04-07 Lot Kroniek 9.2 1 INHOUDSOPGAWE VOORWOORD 3 1. GESKIEDKUNDIGE OORSIG 4 2. KRONOLOGIESE GESKIEDKUNDIGE GEBRUIKE VAN DIE LOT 17 2.1. Ou-Testamentiese tydperk 24 2.2. Nuwe-Testamentiese tydperk 30 2.3. Vroë Kerkgeskiedenis tydperk 30 2.4. Rooms-Katolieke tydperk 34 2.5. Hervormings-tydperk 37 2.6. Kaap de Goede Hoop tydperk 40 2.7. Voortrekker tydperk 43 2.8. Suid-Afrikaanse Hervormde/Gereformeerde Kerke geskiedenis 47 2.9. Republiek van Suid-Afrika tydperk 60 3. HEDENDAAGSE GEBRUIKE VAN DIE LOT IN SUID-AFRIKA 65 3.1. Godsdiens 65 3.2. Politiek/Regering 67 3.3. Verdediging 69 3.4. Regstelsel 70 3.5. Landbou 70 3.6. Onderwys 72 3.7. Handel/Nywerhede/Bankwese/Befondsing/Loterye 73 3.8. Sport en ontspanning 74 3.9. Wetenskap/Waterwese/Geologie/Mynbou 76 AANHANGSELS 1. 135 v.C. – Antiquities of the Jews. Flavius Josephus 80 2. 1700 – Redelijk Geloof. Wilhelmus a Brakel 94 3. 1265 - Summa Theologica. St. Thomas Aquinas 96 4. 1908 - Lotery en Dobbelspel geoorloof? Prof. Dr. W Geesink 112 5. 1931 - Waarom ons lotery veroordeel. -

Appendix AA Glossary of Terms Pertaining to Astrology And

Appendix A A Glossary of Terms Pertaining to Astrology and Divination Aëromancy (a.k.a. nephelomancy): Divination by observing clouds or other atmo- spheric phenomena. Agricultural astronomy: The observed correlation between celestial phenomena, seasonal weather patterns, and the tasks of the agricultural year; this does not involve an astrological attempt to predict future events (apart from the obvious recurrence of seasonal patterns). Alchemy: An ancient body of chemical, philosophical, mystical, and religious lore whose primary focus was the magnum opus (the transmutation of base metals into gold by means of the lapis philosophorum, or philosopher’s stone). Other alchemical operations included the quest for the panacea [elixir of life] and the alkahest [universal solvent]. The oldest extant alchemical texts arose in Egypt during the 1st-4th centuries ad and are attributed to Zosimus of Panopolis and Mary the Jewess. Alchemy was of great interest to Muslim intellectuals, and from them it spread to Mediaeval Europe. Just as astrology was the precursor of mod- ern astronomy, alchemy was the precursor of modern chemistry. Isaac Newton left more than 30,000 manuscript pages on alchemy (more than he wrote on any other subject). King Vakht’ang VI of Georgia was also a student of alchemy. Almanac: Annual weather prognostic, derived from lunar configurations to planets, and configurations of the planets to each other. Alveromancy: Divination by listening for sounds. There are many forms of alvero- mancy, of which the Chechen practice of listening to the ground is a typical example. Angles: (a.k.a. Pivots, Centers): In any horoscope, the four primary points along the ecliptic: Ascendant, m.c., Descendant, l.c. -

Isis Unveiled, Volume 2 — H

ISIS UNVEILED: A MASTER-KEY TO THE MYSTERIES OF ANCIENT AND MODERN SCIENCE AND THEOLOGY H. P. BLAVATSKY CORRESPONDING SECRETARY OF THE THEOSOPHICAL SOCIETY "Cecy est un livre de bonne Foy." — MONTAIGNE VOL. II. — THEOLOGY Blavatsky's first major work on theosophy, examining religion and science in the light of Western and Oriental ancient wisdom and occult and spiritualistic phenomena. Theosophical University Press Online Edition. Electronic version ISBN 1-55700-135-9. This edition may be downloaded for off-line viewing without charge. For ease of searching, no diacritical marks appear in the electronic version of the text. CONTENTS PREFACE (iii - iv) Mrs. Elizabeth Thompson and Baroness Burdett-Coutts. ————————— Volume Second: THE "INFALLIBILITY" OF MODERN RELIGION. CHAPTER 1: THE CHURCH: WHERE IS IT? (1-54) Church statistics / Catholic "miracles" and spiritualistic "phenomena" / Christian and Pagan beliefs compared / Magic and sorcery practised by Christian clergy / Comparative theology a new science / Eastern traditions as to Alexandrian Library / Roman pontiffs imitators of the Hindu Brahm-atma / Christian dogmas derived from heathen philosophy / Doctrine of the Trinity of Pagan origin / Disputes between Gnostics and Church Fathers / Bloody records of Christianity CHAPTER 2: CHRISTIAN CRIMES AND HEATHEN VIRTUES. (55-122) Sorceries of Catherine of Medicis / Occult arts practised by the clergy / Witch-burnings and auto-da-fe of little children / Lying Catholic saints / Pretensions of missionaries in India and China / Sacrilegious tricks of Catholic clergy / Paul a kabalist / Peter not the founder of Roman church / Strict lives of Pagan hierophants / High character of ancient "mysteries" / Jacolliot's account of Hindu fakirs / Christian symbolism derived from Phallic worship / Hindu doctrine of the Pitris / Brahminic spirit-communion / Dangers of untrained mediumship / CHAPTER 3: DIVISIONS AMONGST THE EARLY CHRISTIANS. -

Occult Review V24 N1 Jul 1916

OCCULT REVIEW RALPH SHIRLEY “ NCLLIUS ADDI0TD9 JURABE IN VERBA UAOISTRI ' VOL. X X IV JULY-DECEMBER 1916 LONDON WILLIAM RIDER & SON, LIMITED CATHEDRAL HOUSE, PATERNOSTER ROW, E.O. Build & Tsnacr Frame and Lonooo V Original from Digitized by Google UAD\/ADr\ I IMIX/CDCITV CONTENTS JULY. N otes of the Month : T he S exes H ere PAGB after ; A Strange P arallel ; A W ater D iviner at A nzac ; e tc.............................. The Editor . I T he P rophecies of N ostradamus .... A. Demar-Latour . »4 P opular S uperstitions....................................... Reginald B. Span , . 23 A unt B ar bara’s Ghost Storv .... Gerda M. Calmady Hamlyn . • • • 3« Some A strological P redictions of ti;e late J ohn V a r l e y ....................................... John Varley . 38 V ictims ( V e r s e ) ........................................ Teresa Hooley . 43 A T ale of B arbados ................................ 44 O ur L a d y of Compassion (Verse) . Teresa Hooley • • . 45 Correspondence ............................................. • • • 46 P eriodical L it e r a t u r e ............................... 53 R e v i e w s .......................................................... 56 AUGUST. N otes of the Month : T he D reams of O rlow ; T he W ar and A strology ; etc. The Editor . 59 T he T ramp (V e rse )........................................Lilian Holmes . 71 I nstrumental Communication with the " S pirit W orld ’* .......................................Hereward Carrington 7* T he B attle of the Stars (Verse) . Eva Gore-Booth . 83 A rchdeacon W ilberforce and the Secret o f I ntercessory P r a y e r ..........................Charlotte E. Woods . 84 " T he Good and E vil A ngels ” . -

M2 but Satire, After All, Is Not Argument; There Are, Indeed, Many Who

M2 Borne .Modern Views of our Lord. "They call Him King. They mourn o'er His eclipse, And fill a. cup of ha.lf-contemptuous wine; Foam the froth'd rhetoric for the dea.th-white lips, And ring the changes on the word 'divine.' Divinely gentle-yet a sombre giant; Divinely perfect-yet imperfect man; Divinely calm-yet recklessly defiant; Divinely true-yet half a charlatan. They torture all the record of the Life; Give what from France and Germany they get, To Calvary carry a dissecting-knife, Parisian Patchouli to Olivet." But satire, after all, is not argument; there are, indeed, many who honestly doubt His divinity. It is hard, they say, to deify a man. It would indeed be hard for us to raise a man like ourselves to a Divine position. But if one were not altoge_ther l~ke o~rsel:'~· if one were superh~~a~, should we not gtve H1m H1s Dtvme honours? The dtvtmty of Jesus has been believed for nearly two thousand years ; the burden of proof, therefore, fall upon those who declare Him to be but human. Let them fairly prove that He was so; and without deJ?ending on such questionable theories as legend, tendency, viswn, and hypnotic power, let them explain the uniqueness of His personality, the triumph of His cross, the marvellous perfection of His character and revelation, and that never dying principle of spiritual regeneration which He has been, and is, and shall be to the end of the chapter. F. R. MONTGOMERY HITCHCOCK. --·~-- ART. VII.-BIBLIOMANCY. IBLIO~IANCY, or divination by the Bible, was introduced B into the Church as early as the third century, and has prevailed n;ore or less _since then in every part of Christendo~. -

Lots, the Future and God's Will

12|19 No.16 ien in Ostasien und Europa strateg ungs ältig . Bew nose d Prog Schicksal, Freiheit un page 4 Focus: International Society for the Critical Study of Divination, International Journal and Book Series page 16 Conferences / Workshops: Medieval Collections of Laws as Sources for Mantic Practices page 18 Miscellaneous – Letter of Support Editorial (Prof. Dr. Klaus Herbers) Lots, the Future and God’s Will Fate, Freedom and Prognostication. Strategies for Coping with the Future in East Asia and Europe IMPRINT Lots, the Future and God’s Will Dear Readers, Publisher It is with great joy that we present to you the six- teenth issue of our newsletter fate that covers the IKGF’s activities during the summer term 2018. In the end of the ancient period. Popes during the 9th century condemned such the editorial, IKGF Deputy Director Professor Klaus procedures in the form in which they were practiced, for example, in Bretagne: Herbers addresses the question of whether deci- “This is why we decide that the drawing of lots, by which you make all of sion-making by lots was considered an acceptable your judicial decisions, is no different from what the fathers condemned as practice during the European Middle Ages. If you divination and magic.” (Unde ad illorum similitudinem sortes, quibus vos cuncti have not yet heard about the formation of the Inter- national Society for the Critical Study of Divination in vestris discriminatis iudiciis nichil aliud quam quod illi patres dampnarunt, Director e.V., the focus article that informs about its estab- divinationes et maleficium esse decernimus.)1 Prof. -

Frequently Asked Questions Regarding the Catholic Ministry of Spiritual Liberation and Exorcism

FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS REGARDING THE CATHOLIC MINISTRY OF SPIRITUAL LIBERATION AND EXORCISM On the Ministry in General 1. What is Catholic Exorcism? 2. Where does the Catholic Church derive its authority to “Exorcise”? 3. What are the Types of Catholic Exorcisms? 4. Who is a Catholic Exorcist? 5. Are all Catholic Priests Exorcists? 6. Can Catholic Laypeople be exorcists? 7. What is the Roman Ritual of Exorcism? 8. Is it true that using Latin prayers during exorcisms is more potent than the vernacular? 9. Who needs exorcisms? 10. Can non-Catholics (including non-Christians) be exorcised? 11. Do non-Catholics and non-Christians have some form of deliverance ministry, or what is like an “exorcism” ritual? 12. Can local healers or witch doctors or shamans or “albularyos” exorcise? 13. What is Prayer of Deliverance/Liberations as differentiated from Prayer of Healing? 14. Why is being ministered to by fake Catholic priests or exorcists spiritually dangerous? 15. What is Demonic Retaliation? TOP On Angels in General and Fallen Angels 2 16. Why do we need as Catholics to have an orthodox knowledge about angels and demons? 17. What are Angels? 18. Why did God create angels? 19. Do angels have names, and can we know them? 20. Who are the Fallen Angels? 21. Who is Satan or the Devil? 22. Why did the angels fall? 23. What are the sins of the angels? 24. What did sin do to the Fallen Angels? 25. Can the Fallen Angels repent of their sins and so forgiven by God? 26. Where are the Fallen Angels now? 27. -

Ammianus Macellinus on Oracles in Roman Egypt

FRANZISKA NAETHER MAGICAL TEXTS IN TRISMEGISTOS FRANZISKA NAETHER MAGICAL TEXTS IN TRISMEGISTOS AMMIANUS MARCELLINUS ON ORACLES IN ROMAN EGYPT – OR: WHAT IMPACT HAD CHRISTIANITY ON PAGAN EGYPTIAN DIVINATION?1 From September 2008 German Abstract: Ammianus Marcellinus Bemerkungen über Orakelpraktiken im Bes- Tempel von Abydos werden als Ausgang für diese Studie gewählt. In RG 19, 12, 3-16 erfahren wir, dass das nicht beschiedene Exemplar eines Ticket-Orakels im Tempelarchiv verblieb, um anschließend auf mögliche kaiser- und „staats“-feindliche Inhalte kontrolliert zu werden. Darunter fällt u.a. die seit 11. n. Chr. verbotene Frage nach dem Todeszeitpunkt des Kaisers. Diese Aussage soll anhand der vorhandenen Orakelfragen aus Ägypten überprüft und das in der Datenbank vorhandene Quellenmaterial zu Religion, Ritualtexten, Magie und Divination / Mantik vorgestellt werden. Besondere Berücksichtigung erfährt hierbei die Frage, ob genuin pagane Rituale in frühchristlicher Zeit statistisch gesehen eine Wandlung erfahren. 1. AMMIANUS MARCELLINUS AND THE “EVIL” TICKETS „3 Materiam autem in infinitum quaestionibus extendendis dedit occasio vilis et parva. Oppidum est Abydum in Thebaidis partis situm extremo. Hic Besae dei localiter appellati, oraculum quondam futura pandebat, priscis circumiacentium regionum caerimoniis solitum coli. 4 Et quoniam quidam praesentes, pars per alios desideriorum indice missa scriptura, supplicationibus expresse conceptis, consulta numinum scitabantur, chartulae sive membranae, continentes, quae petebantur, post data quoque responsa interdum remanebant in fano. 5 Ex his aliqua ad imperatorem maligne sunt missa, qui (ut erat angusti pectoris) 1 I would like to express my sincere thanks to M. DEPAUW, W. CLARYSSE and all the others from the team for their valuable critics on an earlier version of this paper. -

The Theosophical Glossary

THE THEOSOPHICAL GLOSSARY Theosophy Trust Books ▪ Theosophical Astrology by Helen Valborg, WQ Judge, HP Blavatsky, Raghavan Iyer ▪ The Bhagavad-Gita and Notes on the Gita by WQ Judge, Robert Crosbie, Raghavan Iyer, HP Blavatsky ▪ Theosophy ~ The Wisdom Religion by the Editorial Board of Theosophy Trust ▪ Self-Actualization and Spiritual Self-Regeneration ▪ Mahatma Gandhi and Buddha's Path to Enlightenment ▪ The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali ▪ Meditation and Self-Study ▪ Wisdom in Action ▪ The Dawning of Wisdom by Raghavan Iyer ▪ The Theosophical Glossary ▪ The Secret Doctrine, Vols. I and II ▪ Isis Unveiled, Vols. I and II ▪ The Key to Theosophy ▪ The Voice of the Silence ▪ The Origins of Self-Consciousness in The Secret Doctrine ▪ Evolution and Intelligent Design in The Secret Doctrine by H.P. Blavatsky ▪ The Ocean of Theosophy by William Q. Judge ▪ Teachers of the Eternal Doctrine by Elton Hall ▪ Symbols of the Eternal Doctrine by Helen Valborg THE THEOSOPHICAL GLOSSARY BY H. P. BLAVATSKY AUTHOR OF "ISIS UNVEILED", "THE SECRET DOCTRINE", "THE KEY TO THEOSOPHY" London: THE THEOSOPHICAL PUBLISHING SOCIETY, 7, DUKE STREET, ADELPHI, W.C. The Path Office: 132, NASSAU STREET, NEW YORK, U.S.A. The Theosophist Office: ADYAR, MADRAS, INDIA. 1892 THEOSOPHY TRUST BOOKS NORFOLK, VA The Theosophical Glossary Copyright © August 25, 2018 by Theosophy Trust All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced by any means - graphic, electronic, or mechanical - including photocopying, recording, taping or by any information storage retrieval system without the written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.