Chapter 1 Voyages Into Space

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

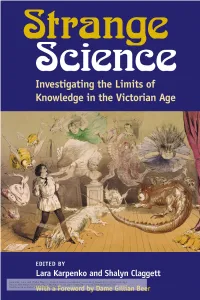

Strange Science: Investigating the Limits of Knowledge in the Victorian

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE Revised Pages Strange Science Revised Pages Revised Pages Strange Science Investigating the Limits of Knowledge in the Victorian Age ••• Lara Karpenko and Shalyn Claggett editors University of Michigan Press Ann Arbor Revised Pages Copyright © 2017 by Lara Karpenko and Shalyn Claggett All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by the University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid- free paper 2020 2019 2018 2017 4 3 2 1 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Karpenko, Lara Pauline, editor. | Claggett, Shalyn R., editor. Title: Strange science : investigating the limits of knowledge in the Victorian Age / Lara Karpenko and Shalyn Claggett, editors. Description: Ann Arbor : University of Michigan Press, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references -

3D Re-Imagining Techniques for Archaeology and Architecture in Film

113stasiowski_Kwartalnik110 22.04.2021 21:43 Strona 169 p. 169-183 113 (2021) Kwartalnik Filmowy „Kwartalnik Filmowy” no. 113 (2021) ISSN: 0452-9502 (Print) ISSN: 2719-2725 (Online) https://doi.org/10.36744/kf.677 © Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 Maciej Stasiowski independent researcher https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3123-6027 Nooks and Crannies in Visible Cities: 3D Re-imagining Techniques for Archaeology and Architecture in Film Keywords: Abstract 3D scanning; With the success of the BBC and PBS series such as Italy’s Invisible Cities (2017), Ancient Invisible Cities (2018), and Pom - LiDAR; peii: New Secrets Revealed (2016), made in collaboration with 3D visualisation ScanLab and employing LiDAR scanning and 3D imaging techniques extensively, popular television programmes grasped the aesthetics of spectral 3D mapping. Visualizing urban topographies previously hidden away from view, these shows put on display technological prowess as means to explore veritably ancient vistas. This article sets out to investigate cinematographic devices and strategies – oscil - lating between perspectives on built heritage championed by two figures central to the 19 th -century discourse on ar - chitecture: Eugène Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc and John Ruskin – manipulating the image in a rivalry for the fullest immersion into a traversable facsimile of past spatialities. 169 113stasiowski_Kwartalnik110 22.04.2021 21:43 Strona 170 Kwartalnik Filmowy 113 (2021) p. 169-183 By the waving of the skeletal trees, closer and closer Through the doors and through the walls and... Justin Sullivan In contemporary ‘moving pictures’, any flight of fancy can be executed by means of digital cinematography and other actions involved in the process of image processing. -

Secret FBI CIA NSA Pentagon KGB Navy Army War

secret FBI CIA NSA Pentagon KGB navy army war please allow some time for the page to load ufo alien secrets cosmic conflict 01 Page ("COSMIC CONFLICT", Vol. 2, Edition 1.2) 01 PAGE NO. 01 Cosmic Conflict & The Da'Ath Wars Page 02 "And the Lord said unto the Serpent... I will put enmity between thee and the woman, and between thy seed and her seed..." -- Genesis ch. 3, vs. 14-15 Page 03 The title of this work will be fully understood as the reader studies the files contained herein. Page Aviation & Simulation 04 Books & CDs The following files, originally appearing in printed form and later transcribed to Daily Forum the present format, are an attempt to tie-together various unanswered Page Environment questions relating to Christian theology, prophecy, cult research, science, 05 Financial News vanguard technology, phenomenology, Einsteinean theory, electromagnetism, aerospace technology, modern and pre history, myth-tradition and legend, Page Galaxy News antediluvian societies, ancient artifacts, cryptozoology, biology and genetic 06 Horoscopes sciences, computer sciences, Ufology, Fortean research, parapsychology, Human Rights conspiraology, missing persons research, human and animal mutilations, Page Japan & Neighbours anthropology, parapolitical sciences, international economics, secret societies, 07 Just Style demonology, advanced astronomy, assassinations, psychic and mental Mind Spirit manipulation or control, international conflict, et al and attempts to bring the Page Quotes of the Day mysteries surrounding these subjects together in a workable and documentable 08 scenario. Religion Page Russia News Many of the sources for these Files include a loose network of hundreds of Science News researchers who have pooled their corroborative information and resources in 09 Search & Directory order to put together the "Grand Scenario" as it is outlined in the Files. -

Investigating the Limits of Knowledge in the Victorian Age

Karpenko, Lara, and Shalyn Claggett. Strange Science: Investigating the Limits of Knowledge In the Victorian Age. E-book, Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2016, https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.9357346. Downloaded on behalf of Unknown Institution Revised Pages Strange Science Karpenko, Lara, and Shalyn Claggett. Strange Science: Investigating the Limits of Knowledge In the Victorian Age. E-book, Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2016, https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.9357346. Downloaded on behalf of Unknown Institution Revised Pages Karpenko, Lara, and Shalyn Claggett. Strange Science: Investigating the Limits of Knowledge In the Victorian Age. E-book, Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2016, https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.9357346. Downloaded on behalf of Unknown Institution Revised Pages Strange Science Investigating the Limits of Knowledge in the Victorian Age ••• Lara Karpenko and Shalyn Claggett editors University of Michigan Press Ann Arbor Karpenko, Lara, and Shalyn Claggett. Strange Science: Investigating the Limits of Knowledge In the Victorian Age. E-book, Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2016, https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.9357346. Downloaded on behalf of Unknown Institution Revised Pages Copyright © 2017 by Lara Karpenko and Shalyn Claggett All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by the University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid- free paper 2020 2019 2018 2017 4 3 2 1 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. -

Corpses, Coasts, and Carriages: Gothic Cornwall, 1840-1913

Corpses, Coasts, and Carriages: Gothic Cornwall, 1840-1913 Submitted by Joan Passey to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in September 2019 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Joan Passey Signature: ………………………………………………………….. Words: 91,425 1 Abstract While there are defined Irish, Welsh, and Scottish Gothic traditions, there has been a notable critical absence of a Cornish Gothic tradition, despite multiple canonical and less-canonical authors penning Gothic stories set in Cornwall throughout the long nineteenth century. This critical oversight is part of a longer tradition of eliding Cornwall from literary and cultural histories—even from those to which it has particular relevance, such as histories of the industrial revolution (in which its mining industry was a major contributor), and the birth of the tourist industry, which has shaped the county and its economy through to the present day. This thesis will rectify this gap in criticism to propose a Cornish Gothic tradition. It will investigate Gothic texts set in Cornwall in the long nineteenth century to establish a distinct and particular tradition entrenched in Cornwall’s own quest for particularity from other Celtic nations and English regions. It will demonstrate how the boom in Cornish Gothic texts was spurred by major changes occurring in the county in the period, including being the last county to be connected to the national rail network, the death of the mining industry, the birth of the tourist industry, large-scale maritime disaster on its coasts, and the resituating of the legendary King Arthur in Tintagel with the publication of Tennyson’s Idylls of the King. -

Invisible Eagle, the History of Nazi Occultism

www.GetPedia.com * More than 500,000 Interesting Articles waiting for you . * The Ebook starts from the next page : Enjoy ! * Say hello to my cat "Meme" Everything about Internet Technology! Chose your section ● Auctions ● Network Marketing ● Business ● Online Promotion ● Computers ● Search Engines ● Domain Names ● Site Promotion ● Downloads ● Software ● eBay ● Technology ● Ebooks ● Video Conferencing ● Ecommerce ● VOIP ● Email Marketing ● Web Design ● Internet Marketing ● Web Development ● HTML ● Web Hosting ● JavaScript ● WIFI ● MP3 Invisible Eagle By Alan Baker The History of Nazi Occultism Contents Acknowledgements Introduction: search for a map of hell 1 - Ancestry, blood and nature The Mystical Origins of National Socialism 2 - Fantastic prehistory The Lost Aryan Homeland 3 - A hideous strength The Vril Society 4 - The phantom kingdom The Nazi-Tibet Connection 5 - Talisman of conquest The Spear of Longinus 6 - Ordinary madness Heinrich Himmler and the SS 7 - The secret at the heart of the world Nazi Cosmology and Belief in the Hollow Earth 8 - The cloud Reich Nazi Flying Discs 9 - Invisible Eagle Rumours of Nazi Survival to the Present Conclusion: the myth machine The Reality and Fantasy of Nazi Occultism Notes Bibliography and suggested further reading Index The historian may be rational, but history is not. - Louis Pauwels and Jacques Bergier 'I'm a sceptic.' 'No, you're only incredulous, a doubter, and that's different.' - Umberto Eco, Foucault's Pendulum Acknowledgements Grateful acknowledgement is given for permission to quote from the following previously published material: The Coming Race by E. G. E. Bulwer Lytton, published by Sutton Publishing, Stroud, Gloucestershire, 1995. Arktos The Polar Myth in Science, Symbolism, and Nazi Survival by Joscelyn Godwin, published by Thames and Hudson, London, 1993. -

Hollow Earth 101

307-8 Winter/Spring 2013-2014 SFRA Editor A publicationRe of the Scienceview Fiction Research Association Chris Pak University of Birmingham, Edgbaston, Birmingham, B15 2TT, UK. In this issue [email protected] SFRA Review Business Managing Editor Introductions ........................................................................................................2 Lars Schmeink Universität Hamburg, Institut für Anglis- tik und Amerikanistik, Von Melle Park 6 SFRA Business 20146 Hamburg. Meanwhile, at the EC HQ . ............................................................................2 [email protected] Upcoming Joint WisCon/SFRA ..........................................................................3 Making Connections ............................................................................................4 Nonfiction Editor Dominick Grace Brescia University College, 1285 Western Feature Interview Rd, London ON, N6G 3R4, Canada An Interview with Frederick Turner ..................................................................5 phone: 519-432-8353 ext. 28244. [email protected] Feature 101 Assistant Nonfiction Editor Hollow Earth 101 ................................................................................................13 Kevin Pinkham The Nursing Profession in the Fictional Star Trek Future. ...........................23 College of Arts and Sciences, Nyack College, 1 South Boulevard, Nyack, NY 10960 Nonfiction Reviews phone: 845-675-4526845-675-4526. Parabolas of Science Fiction ...............................................................................27 -

Hollow Earth Fiction and Environmental Form in the Late Nineteenth Century

Nineteenth-Century Contexts An Interdisciplinary Journal ISSN: 0890-5495 (Print) 1477-2663 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/gncc20 Hollow Earth Fiction and Environmental Form in the Late Nineteenth Century Elizabeth Hope Chang To cite this article: Elizabeth Hope Chang (2016) Hollow Earth Fiction and Environmental Form in the Late Nineteenth Century, Nineteenth-Century Contexts, 38:5, 387-397, DOI: 10.1080/08905495.2016.1219190 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08905495.2016.1219190 Published online: 05 Sep 2016. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 8 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=gncc20 Download by: [Dr Elizabeth Chang] Date: 15 September 2016, At: 18:22 NINETEENTH-CENTURY CONTEXTS, 2016 VOL. 38, NO. 5, 387–397 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08905495.2016.1219190 Hollow Earth Fiction and Environmental Form in the Late Nineteenth Century Elizabeth Hope Chang Department of English, University of Missouri, Columbia, Missouri, USA When the ill-fated Arthur Gordon Pym, hero of Edgar Allen Poe’s 1838 text The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket, sails from the temperate Antarctic island of Tsalal into the polar sea towards a “limitless cataract, rolling silently into the sea from some immense and far-distant rampart in the heavens” beyond which is visible “a chaos of flitting and indistinct images,” he also sails from his pastiche of exploration and travel narratives into the gulf of another, even more unusual, kind of genre fiction (Poe 248). -

Science Fiction Review #15V04n04

SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW 1.25 SFR INTERVIEWS $ L. SPRAGUE DE CAMP THIS PROVES IT! WE'VE FOUND THE HOME PLANET! THE BEST QV STEPHEI FABIAN PRESENTED BY s Loompanics Unlimited Box 2 64 Mason, Michigan 48854 / Fifty of Stephen Fabian’s finest drawings from Galaxy, If, Whispers, The Occult Love craft , Outworlds, The Miscast Barbarian , and more, more, more,.. Including fifteen never before published drawings, done especially for this book . Each drawing is printed on one side of 8f x 11 80 lb. paper, easily removable for framings Truly a collector’s item, this is an art book to be treasured now and in the years to come. THE BEST OF STEPHEN FABIAN will be released in February in a limited, numbered edition of 1,500 copies. RESERVE YOURS NOW WHILE THE SUPPLY LASTS. LOOMPANICS UNLIMITED BOX 264 M4S0N, MICHIGAN 48854 Sirs » Enclosed is $ . Please reserve copies of THE BEST OF STEPHEN FABIAN @> $12.50 each. Name Addres s C ity S tat e _____ 2 ip. 1 —A — ) SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW Formerly THE ALIEN CRITIC^ P. O. Box 11408 COVER BY GRANT CANFIELD Portland, OR November, 1975 Volume Four, Number Four ALIEN THOUGHTS 4 97211 Whole Number Fifteen SPEC FIC AND THE PERRY RHODAN GHETTO RICHARD E. GEIS By Donald C. Thompson 6 Editor & Publ isher Commentary by R. E.G. With REV I EWS A Letter from Bob Silverberg ALL UNCREDITED WRITING IS A Ouote from Silverberg THE LAND LEVIATHAN And a Commentary by I RON CAGE BY THE EDITOR IN ONE GEIS Darrell Schweitzer Reviewed by Lynne Holdom- 10 OR ANOTHER THE CAMP OF THE SAINTS AN' INTERVIEW WITH Reviewed by Lynne Holdom- 16 PUBLISHED QUARTERLY L. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Etidorhpa Strange History of a Mysterious Being and an Incredible Journey Inside the Earth by John U ETIDORHPA DE JOHN URI LLOYD PDF

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Etidorhpa Strange History of a Mysterious Being and an Incredible Journey Inside the Earth by John U ETIDORHPA DE JOHN URI LLOYD PDF. Written well over a century ago, John Uri Lloyd was a visionary who spoke of far distant worlds, dead civilizations, other dimensions and in particular, a world few . Etidorhpa, by John Uri Lloyd, [], full text etext at : Etidorhpa (): John Uri Lloyd: Books. Etidorhpa and millions of other books are available for Amazon Kindle. Learn more. Author: Faerr Zulkigore Country: Angola Language: English (Spanish) Genre: Relationship Published (Last): 1 January 2012 Pages: 492 PDF File Size: 5.35 Mb ePub File Size: 16.62 Mb ISBN: 586-8-94241-431-8 Downloads: 7585 Price: Free* [ *Free Regsitration Required ] Uploader: Mesho. From a FedEx package sent by his great granddaughter in California, his eyeglasses tumble out. There is quite a bit of philosophical discourse about humans and their lost ways, but still plenty of alluring surprises such as gigantic magic mushrooms and boats that glide effortlessly and at great speeds on glass, sort of lakes. Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Pedro Santos rated it liked it Jul 21, Augustus Knapp are eerily superb, well worth checking out. This was a trippy, trippy book! What did the book mean? Etidorhpa – Wikipedia. Victoria Moorwood – December 21, Mar 24, Wreade rated it liked it Shelves: Immerse yourselves in this one and give me a shout! Aug 04, Micah Dunlap rated it liked it. His mood is melancholy. Neal Wilgus, in his introduction to this edition, thinks that this novel was based on Lloyd’s own experience, for his life long pharmaceutical research must have brought him in contact with hallucinogenic substances. -

American Hollow Earth Narratives from the 1820S to 1920

American Hollow Earth Narratives From the 1820s to 1920 Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of the University of Liverpool for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy by Michelle Kathryn Yost August 2014 Abstract With the disappearance of terra incognita from nineteenth century maps, new lands of imagination emerged in literature, supplanting the blank spaces on the globe with blank spaces inside the globe, the terra cava. Beginning with Symmes’s Theory of Concentric Spheres from 1818, dozens of American authors wrote fictions set in a hollow or semi- hollow earth. This setting provided a space for authors to experiment with contemporary issues of imperialism, science, faith, and socio-political reforms. The purpose of this thesis is one of literary archaeology, examining the American hollow earth narrative, which peaked in publication numbers between 1880 and 1920, most of which was forgotten as exploration of the Poles disproved Symmes’s theory of Polar openings into a hollow, habitable world. Though there have been some general studies of hollow earth and subterranean literature, there has never been a focused study of nineteenth century American hollow earth literature and its relationship to contemporary culture. The first chapter explores the history of John Cleves Symmes, Jr and his theory in the early nineteenth century, and the influence is had on American politics, literature, and scientific thought. In the subsequent three chapters, the terra cava narratives published between 1880 and 1920 are explored in three categories: the imperial, the spiritual, and the utopian. All of these elements reflect distinct American concerns during the fin de siècle about the country’s expansion, the closing of the frontier, variations in Christian theology, the development of Spiritualism, the women’s rights movement, and socio-economic reforms meant to improve American life. -

The Colonization of Tiamat

The Colonization of Tiamat Part V: The Annunaki Strike Back --daniel It is a dark time for the Rebellion. Although the misconceptions of modern astronomy have been destroyed, conventional astronomers have driven the Rebel forces from their hidden basement and pursued them across the solar systems, still claiming they are galaxies. Evading the dreaded Royal Astronomical Society, a group of free thinkers led by Daniel Earthwalker has established a new secret basement in the remote ice state of Montana. The evil lord Darth Enlil, obsessed with finding young Earthwalker, has dispatched thousands of seraphim into the far reaches of the wilderness… Many common sense concepts accepted as truth in the 19th century have now been delegated to the realm of “poopoo” by our hyper-educated, modern scientific thinkers. And so it was with the concept of the æther—or more accurately, being so embarrassed to discover that these 19th century researchers were actually right, these scientists hid the concept in the dark—dark matter,1 to be specific. None of the 19th century æther researchers are mentioned in dark matter research so these experts can get their own claim to fame for this brilliant, new, centuries-old idea to explain why the Universe isn’t behaving the way it should… according to modern theory. To assist in the later developments of the colonization of Tiamat, two concepts are going to be introduced, again using the context of Dewey B. Larson’s Reciprocal System of theory:2 1. A new concept of æther, being that of the projection of Larson’s cosmic sector (the realm of 3D, coordinate time and clock space) into yin space (“equivalent” or vortex space).