Gods of the Hills”: Buying Tradition from a Sole Source

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bennington Battlefield 4Th Grade Activities

Battle of Bennington Fourth Grade Curriculum Guide Compiled by Katie Brownell 2014 Introduction: This curriculum guide is to serve as station plans for a fourth grade field trip to the Bennington Battlefield site. The students going on the field trip should be divided into small groups and then assigned to move between the stations described in this curriculum guide. A teacher or parent volunteer should be assigned to each station as well to ensure the stations are well conducted. Stations and Objectives: Each station should last approximately forty minutes, after which allow about five minutes to transition to the next station. The Story of the Battle Presentation: given previously to the field trip o Learn the historical context of the Battle of Bennington. o Understand why the battle was fought and who was involved. o Understand significance of the battle and conjecture how the battle may have affected the outcome of the Revolutionary War. Mapping Station: At the top of Hessian Hill using the relief map. o Analyze and discuss the transportation needs of people/armies during the 18th Century in this region based on information presented in the relief map at the top of Hessian Hill. o Create strategy for defense using relief map on top of Hessian Hill if you were Colonel Baum trying to defend it from a Colonial Attack. The Hessian Experience o Understand the point of view of the German soldiers participating in the battle. o Learn about some of the difficulties faced by the British. Historical Document Match Up: In field near upper parking lot* o Analyze documents/vignettes of historical people who played a role during the battle of Bennington. -

Ethan Allen and the Green Mountain Boys Wyatt Earp Eliot Ness Zorro

FACT? FICTION?FICTION? Ethan Allen and® the Green Mountain Boys Audrey Ades 2001 SW 31st Avenue Hallandale, FL 33009 www.mitchelllane.com Copyright © 2018 by Mitchell Lane Publishers. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without written permission from the publisher. Printed and bound in the United States of America. Printing 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Audie Murphy Francis Marion Buffalo Bill Cody The Pony Express The Buffalo Soldiers Robin Hood Davy Crockett The Tuskegee Airmen Ethan Allen and the Green Mountain Boys Wyatt Earp Eliot Ness Zorro Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Ades, Audrey, author. Title: Ethan Allen and the Green Mountain Boys / by Audrey Ades. Description: Hallandale, FL : Mitchell Lane Publishers, 2018. | Series: Fact or fiction? | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Audience: Age 8-11. | Audience: Grade 4 to 6. Identifiers: LCCN 2017009127 | ISBN 9781612289526 (library bound) Subjects: LCSH: Allen, Ethan, 1738–1789. | Soldiers—United States—Biography. | United States—History—Revolution, 1775-1783—Biography. | Vermont—History—Revolution, 1775-1783. Classification: LCC E207.A4 G34 2017 | DDC 974.3/03092 [B] —dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017009127 eBook ISBN: 978-1-61228-953-3 CONTENTS Chapter 1 Land, Liberty, and the Green Mountain Boys .............................5 Chapter 2 Ethan: Strong and Solid ................................11 Chapter 3 War ............................................................................15 Chapter 4 Fort Ticonderoga -

Primary Sources Battle of Bennington Unit

Primary Sources Battle of Bennington Unit: Massachusetts Militia, Col. Simonds, Capt. Michael Holcomb James Holcomb Pension Application of James Holcomb R 5128 Holcomb was born 8 June 1764 and is thus 12 years old (!) when he first enlisted on 4 March 1777 in Sheffield, MA, for one year as a waiter in the Company commanded by his uncle Capt. Michael Holcomb. In April or May 1778, he enlisted as a fifer in Capt. Deming’s Massachusetts Militia Company. “That he attended his uncle in every alarm until some time in August when the Company were ordered to Bennington in Vermont […] arriving at the latter place on the 15th of the same month – that on the 16th his company joined the other Berkshire militia under the command of Col. Symonds – that on the 17th an engagement took place between a detachment of the British troops under the command of Col. Baum and Brechman, and the Americans under general Stark and Col. Warner, that he himself was not in the action, having with some others been left to take care of some baggage – that he thinks about seven Hundred prisoners were taken and that he believes the whole or a greater part of them were Germans having never found one of them able to converse in English. That he attended his uncle the Captain who was one of the guard appointed for that purpose in conducting the prisoners into the County of Berkshire, where they were billeted amongst the inhabitants”. From there he marches with his uncle to Stillwater. In May 1781, just before his 17th birthday, he enlisted for nine months in Capt. -

Founding Fathers" in American History Dissertations

EVOLVING OUR HEROES: AN ANALYSIS OF FOUNDERS AND "FOUNDING FATHERS" IN AMERICAN HISTORY DISSERTATIONS John M. Stawicki A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS December 2019 Committee: Andrew Schocket, Advisor Ruth Herndon Scott Martin © 2019 John Stawicki All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Andrew Schocket, Advisor This thesis studies scholarly memory of the American founders and “Founding Fathers” via inclusion in American dissertations. Using eighty-one semi-randomly and diversely selected founders as case subjects to examine and trace how individual, group, and collective founder interest evolved over time, this thesis uniquely analyzes 20th and 21st Century Revolutionary American scholarship on the founders by dividing it five distinct periods, with the most recent period coinciding with “founders chic.” Using data analysis and topic modeling, this thesis engages three primary historiographic questions: What founders are most prevalent in Revolutionary scholarship? Are social, cultural, and “from below” histories increasing? And if said histories are increasing, are the “New Founders,” individuals only recently considered vital to the era, posited by these histories outnumbering the Top Seven Founders (George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, Benjamin Franklin, and Thomas Paine) in founder scholarship? The thesis concludes that the Top Seven Founders have always dominated founder dissertation scholarship, that social, cultural, and “from below” histories are increasing, and that social categorical and “New Founder” histories are steadily increasing as Top Seven Founder studies are slowly decreasing, trends that may shift the Revolutionary America field away from the Top Seven Founders in future years, but is not yet significantly doing so. -

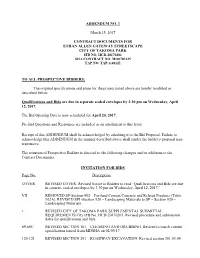

ADDENDUM NO. 1 March 15, 2017 CONTRACT DOCUMENTS FOR

ADDENDUM NO. 1 March 15, 2017 CONTRACT DOCUMENTS FOR ETHAN ALLEN GATEWAY STREETSCAPE CITY OF TAKOMA PARK IFB NO. HCD-20170201 SHA CONTRACT NO. MO0705125 FAP NO. TAP-3(481)E TO ALL PROSPECTIVE BIDDERS: The original specifications and plans for the project noted above are hereby modified as described below: Qualifications and Bids are due in separate sealed envelopes by 3:30 pm on Wednesday, April 12, 2017. The Bid Opening Date is now scheduled for April 24, 2017. Pre-Bid Questions and Responses are included as an attachment to this letter. Receipt of this ADDENDUM shall be acknowledged by attaching it to the Bid Proposal. Failure to acknowledge this ADDENDUM in the manner described above shall render the bidder’s proposal non- responsive. The attention of Prospective Bidders is directed to the following changes and/or additions to the Contract Documents: INVITATION FOR BIDS Page No. Description COVER REVISED COVER. Revised Notice to Bidders to read “Qualifications and Bids are due in separate sealed envelopes by 3:30 pm on Wednesday, April 12, 2017.” VII REMOVED SP-Section-902 – Portland Cement Concrete and Related Products (Table 902A). REVISED SPI -Section 920 – Landscaping Materials to SP – Section 920 – Landscaping Materials. 1 REVISED CITY OF TAKOMA PARK SUPPLEMENTAL SUBMITTAL REQUIREMENTS City IFB No. HCD-20170201. Revised procedure and submission dates for qualifications and bids. 89-89C REVISED SECTION 101 – CLEARING AND GRUBBING. Revised to match current specification issued from MDSHA on 02/09/17. 120-121 REVISED SECTION 201 – ROADWAY EXCAVATION. Revised section 201.03.09. Ethan Allen Avenue Gateway Addendum No. -

History Timeline

27 25 History 26 Timeline Walloomsac Rd. Old Bennington 1749 Charter granted to Bennington by Map and Key New Hampshire Governor Benning 24 Wentworth 1 Pliney Dewey House 23 2 1761 Bennington settled by families from 22 Hiram Waters House Massachusettes and Connecticut 3 Isaiah Hendryx House 21 4 Jedidiah Dewey House 1762 Benjamin Harwood, first child born 20 5 Roberts House Monument Ave. Monument in Bennington 6 Monument to William Lloyd Garrison 19 7 Colonel Nathaniel Brush House 1763 Meetinghouse built, first Protestant 17 8 Walloomsac Inn church in Vermont 18 Bank St. 9 Old First Church 1777 Vermont declares itself an 16 10 Site of the Meetinghouse 1763 independent state 15 11 Site of the County Courthouse 1847 12 Site of Ethan Allen’s House 1777 Battle of Bennington on August 16 13 Asa Hyde House 1791 Vermont joins the United States 14 Catamount Tavern 1767 as the 14th State after fourteen 14 15 Old Academy years as an independent republic 16 Site of Samuel Robinson’s log cabin Main St. 13 17 Samuel Raymond House 1806 Old First Church dedicated 12 18 General David Robinson House 11 19 Richard Carpenter House 1828 William Lloyd Garrison publishes 8 10 Ave. Monument Journal of the Times 9 20 Uel Robinson House VT Route 9 / West Rd. 21 Ellenwood-Daniel Conkling House 1841 Downtown Bennington, called 7 6 5 22 Fay-Brown House “Algiers,” develops 23 Governor John Robinson House 4 1891 Dedication of Bennington Battle 24 Captain David Robinson House Monument celebrating the Battle 3 25 Bennington Battle Monument of Bennington in 1777 and the 2 1 26 Monument to Colonel Seth Warner Centennial of Vermont statehood 27 Monument to General John Stark **This map is not to scale Monument Ave. -

William Marsh, 'A Rather Shadowy Figure

William Marsh, ‘a rather shadowy figure,’ crossed boundaries both national and political Vermont holds a unique but little-known place in eighteenth-century American and Canadian history. During the 1770s William Marsh and many others who had migrated from Connecticut and Massachusetts to take up lands granted by New Hampshire Governor Benning Wentworth, faced severe chal- lenges to their land titles because New York also claimed the area between the Connecticut and Hudson rivers, known as “the New Hampshire Grants.” New York’s aggressive pursuit of its claims generated strong political tensions and an- imosity. When the American Revolution began, the settlers on the Grants joined the patriot cause, expecting that a new national regime would counter New York and recognize their titles. During the war the American Continental Congress declined to deal with the New Hampshire settlers’ claims. When the Grants settlers then proposed to become a state separate from New York, the Congress denied them separate status. As a consequence, the New Hampshire grantees declared independence in 1777 and in 1778 constituted themselves as an independent republic named Vermont, which existed until 1791 when it became the 14th state in the Ameri- can Union. Most of the creators of Vermont played out their roles, and their lives ended in obscurity. Americans remember Ethan Allen and his Green Mountain Boys and their military actions early in the Revolution. But Allen was a British captive during the critical years of Vermont’s formation, 1775-1778. A few oth- ers, some of them later Loyalists, laid the foundations for Vermont’s recognition and stability. -

Read the Article Ethan Allen: Vermont Hero from the Historic Roots

HISTORIC ROOTS HISTORIC ROOTS Ann E. Cooper, Editor Deborah P. Clifford, Associate Editor ADVISORY BOARD Sally Anderson Nancy Chard Marianne Doe Mary Leahy Robert Lucenti Caroline L. Morse Meg Ostrum Michael Sherman Marshall True Catherine Wood Publication of Historic Roots is made possible in part by grants from the A.D. Henderson Foundation, the Vermont Council on the Humanities, and Vermont-NEA. A Magazine of Vermont History Vol. 3 April 1998 No. 1 BENEATH THE SURFACE ETHAN ALLEN: VERMONT HERO Ethan Allen is without doubt the most famous Vermonter. Because he and his Green Mountain Boys captured Fort Ticonderoga in the early days of the Revolution, his fame has gone far beyond Vermont. But we really don't know that much about the man himself. There are no known pictures of him that were drawn from life. We have books he wrote on religion and government, but few letters. What we know is mostly what others wrote and told about him. We do know that Ethan Allen was very tall, had a fierce temper and a loud voice. He drank a lot. He loved a good fight. Whatever he did or said pleased some people, but made many others angry. But one thing is true, whatever he wrote or did, people noticed. He was often in trouble. He was kicked out of Northampton, Massachusetts for his The artist used descriptions of Ethan Allen to make this rowdy behavior. He left his home town of portrait. Salisbury, Connecticut in debt, having angered many of the religious and civic leaders of the town. -

Battle of Bennington | Facts, History, Summary, Battlefield

Battle of Bennington By Russell Yost The Battle of Bennington was an influential battle in the American Revolutionary War that took place on August 16, 1777, in Walloomsac, New York, about 10 miles from Bennington, Vermont. A rebel force of 2,000 men, primarily made up of New Hampshire and Massachusetts militiamen, led by General John Stark, and reinforced by men led by Colonel Seth Warner and members of the notorious Green Mountain Boys, decisively defeated a detachment of General John Burgoyne’s army led by Lieutenant Colonel Friedrich Baum, and supported by more men under Lieutenant Colonel Heinrich von Breymann. This victory set the stage for the defeat of Burgoyne at the Battle of Saratoga. Baum’s men of dismounted Brunswick dragoons, Canadians, Loyalists, and Indians totaled around 700 and was sent by Burgoyne to raid Bennington in the disputed New Hampshire Grants area for horses, draft animals, and other supplies. Unfortunately, Burgoyne had faulty intelligence as he ran into 1,500 militiamen under the command of General John Stark. This fatal mistake would cost Burgoyne one of his commanders when Baum fell and many casualties. Bennington was a key victory in the American Revolution and it does not receive the Battle of Bennington | Facts, History, Summary, Battlefield http://thehistoryjunkie.com/battle-of-bennington-facts/ recognition that it deserves. One could argue that without Bennington that there would not hav been a victory at Saratoga since the Battle of Bennington reduced Burgoyne’s men by close 1,000, hurt his standing with the Indians and deprived him of necessary supplies. -

First Blow for Freedom

FIRST BLOW FOR FREEDOM What happened in Westminster, Vermont, on the Now this is where the famous character Ethan 13th of March, 1775? Only a plaque and the two Allen comes in. Men living in the Grants knew that to tombstones of the men who were killed mark the spot win the fight with New York they had to be where the event took place. The courthouse has long organized. They selected their friend, Ethan Allen, been gone. No one who was there is still alive to tell from Salisbury, Connecticut, to be their leader. In the story. We only know what happened from what the spring of 1770, he came north to help the Grants has been written down. owners. The events of that famous evening were the result His first attempt was to fight their battle in court. of tensions between the settlers in what would soon In preparation he went to the Governor of New be called Vermont and the "Yorkers," their neigh• Hampshire to get the deeds for the land sold to the bors across the border in New York State. To under• Grants settlers. After accomplishing this he hired a stand what happened that night and why, we have to fine Connecticut lawyer to defend the settlers in look back to a time almost 25 years earlier. court. The trial was in Albany, New York. The court In 1749 New Hampshire's Governor, Benning was prejudiced in favor of the New York position. Wentworth, began selling land west of the Connecti• They did not consider the settlers' land deeds as cut River. -

How Ethan Allen and His Brothers Chased Success in the Real Estate Business

A grand plan: Flirting with treason How Ethan Allen and his brothers chased success in the real estate business John J. Duffy Ira Allen 1751-1814 Bennington Museum collection In memorials produced long after his death in 1789, Ethan Allen has been remembered in statues in Vermont and in the Congressional Hall of Statuary in Washington, DC; in military posts named for him in Virginia during the Civil War and in Colchester, Vermont, an 1890s post, its original structures now residential and commercial sites. Though Allen sailed the seas only as a British prisoner in 1776, two Union coastal defense boats dis- played his name in the 1860s. A century later, the nuclear submarine Ethan Allen fired the first nuclear-tipped missile from below the ocean’s surface in the early 1960s. Ethan is probably best remembered from mostly fictional tales and stories about his heroic and other deeds, especially the pre-dawn capture of the British forts at Ticonderoga and Crown Point in May 1775 during the earliest months of the American War for Independence from Great Britain. Some say he was the most important founder of Vermont. On that latter point, however, remembrances of Ethan Allen seem to forget that he was far from Vermont when the state’s independence was de- Walloomsack Review 14 clared in 1777. He had been a prisoner of the British since September 1775 when he was captured after foolishly attacking Montreal with only one-hun- dred poorly armed Americans and Canadians against a force of five-hundred defenders – British regulars, Loyalist militia, and Mohawk warriors. -

Maryland Historical Magazine, 1911, Volume 6, Issue No. 4

|s/\S/\5C BftftM-^ MARYLAND HISTORICAL MAGAZINE VOL. VI. DECEMBER, 1911. No. 4. VESTEY PROCEEDINGS, ST. ANN'S PARISH, ANNAPOLIS, MD. [St. Ann's Parish, originally known as Middle Neck Parish, was one of thirty-five which were established by '' An Act for the service of Almighty God and the establishment of the Protestant Eeligion within this province," passed in 1692 (Archives, 13 : 425), but by reason of the loss of the first twelve pages of the Vestry records, the exact date of its organization cannot be established. In the Proceedings of the Council, October 23, 1696 (Archives, 23 : 19), the following appears : "Ann Arrundell County is Divided into fFour parishes viz' Herring Creek. South Kiver. Middle Neck & Broad Neck . Middle Neck Parish is Scituated betwixt South Kiver and Severn River. Vestrymen for the sa Parish Chosen &ca Viz* Mr Thomas Bland, Mr Richard Wharfield, Mr Jacob Harness, Mr. Wm. Brown, Mr. Corne Howard. Taxables 374" '' An Act for appointing persons to Treat with Workmen for the building a Church att the Porte of Annapolis" passed at the session of June-July, 1699, may be found in the Archives, 22:580. Fur- ther details as to this parish may be had from Rev. Ethan Allen's "Historical Notices of St. Ann's Parish" and Riley's "Ancient City," p. 68. Some notes concerning the Rev. Peregrine Coney, the first incumbent of St. Ann's were printed in this Magazine, 5:290, 291.] At a Vestry held for St. Ann's Parish the 14tl1 day of March An0 Dom. 1712. Present, The reverend Mr Edw* Butler, Sam1 Young, Esq ., Thos.