The Wittelsbach Blue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Królewski Kościół Katedralny Na Wawelu. W Rocznicę Konsekracji

Tomasz Węcławowicz Królewski kościół katedralny na Wawelu W rocznicę konsekracji 1364-2014 Royal Cathedral Church on Wawel Hill in Krakow Jubilee of the Consecration 1364-2014 Dekoracja zachodniej ściany katedry dobitnie ilustruje powiązanie św. Stanisława z ideą polityczną ostatnich władców z dynastii Piastów. Szczyt wieńczy figura św. Stani sława, poniżej na drzwiach widnieje monogram króla Kazimierza Wielkiego - a między nimi Orzeł, herb Królestwa Polskiego - heraldyczny łącznik spajający dwie personifikacje religijnej i świeckiej władzy. [...] Dlatego krakowska katedra jest w każdym znaczeniu tego słowa „kościołem królewskim” - a przy tym jedną z najwcześniejszych takich realizacji w Europie Środkowej. Paul Crossley, Gothic Architecture in the Reign of Kazimir the Great, Kraków 1985 [The] demonstration of the link between St Stanislaw and the political ideology of the last Piast King is provided by the decoration of the west front of the cathedral. Above, in the gable is the figure of St Stanislaw; below, on the doors, is the pronounced signature of Kazimir the Great; and between them, as a heraldic link between these two personifica tions of the religious and secular authority, is the Polish eagle, the arms of Poland [...] In every sense of the word, therefore, Krakow cathedral is - a Konigskirche. It is moreover one of the earliest of its kind in Central Europe. Paul Crossley, Gothic Architecture in the Reign of Kazimir the Great, Krakow 1985 Tomasz Węcławowicz Królewski kościół katedralny na Wawelu W rocznicę konsekracji 1364-2014 Royal Cathedral Church on Wawel Hill in Krakow Jubilee of the Consecration 1364-2014 Kraków 2014 UNIW ERSYTET PAPIESKI JANA PAWŁA II WYDZIAŁ HISTORII I DZIEDZICTWA KULTUROWEGO PONTIFICAL UNIVERSITY OF JOH N PAUL II FACULTY OF HISTORY AND CULTURAL HERITAGE KRAKOWSKA AKADEMIA IM. -

11. Heine and Shakespeare

https://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2021 Roger Paulin This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt the text and to make commercial use of the text providing attribution is made to the authors (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Roger Paulin, From Goethe to Gundolf: Essays on German Literature and Culture. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2021, https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0258 Copyright and permissions for the reuse of many of the images included in this publication differ from the above. Copyright and permissions information for images is provided separately in the List of Illustrations. In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit, https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0258#copyright Further details about CC-BY licenses are available at, https://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by/4.0/ All external links were active at the time of publication unless otherwise stated and have been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web Updated digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0258#resources Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. ISBN Paperback: 9781800642126 ISBN Hardback: 9781800642133 ISBN Digital (PDF): 9781800642140 ISBN Digital ebook (epub): 9781800642157 ISBN Digital ebook (mobi): 9781800642164 ISBN Digital (XML): 9781800642171 DOI: 10.11647/OBP.0258 Cover photo and design by Andrew Corbett, CC-BY 4.0. -

Charles V, Monarchia Universalis and the Law of Nations (1515-1530)

+(,121/,1( Citation: 71 Tijdschrift voor Rechtsgeschiedenis 79 2003 Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline Mon Jan 30 03:58:51 2017 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at http://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. -- To obtain permission to use this article beyond the scope of your HeinOnline license, please use: Copyright Information CHARLES V, MONARCHIA UNIVERSALIS AND THE LAW OF NATIONS (1515-1530) by RANDALL LESAFFER (Tilburg and Leuven)* Introduction Nowadays most international legal historians agree that the first half of the sixteenth century - coinciding with the life of the emperor Charles V (1500- 1558) - marked the collapse of the medieval European order and the very first origins of the modem state system'. Though it took to the end of the seven- teenth century for the modem law of nations, based on the idea of state sover- eignty, to be formed, the roots of many of its concepts and institutions can be situated in this period2 . While all this might be true in retrospect, it would be by far overstretching the point to state that the victory of the emerging sovereign state over the medieval system was a foregone conclusion for the politicians and lawyers of * I am greatly indebted to professor James Crawford (Cambridge), professor Karl- Heinz Ziegler (Hamburg) and Mrs. Norah Engmann-Gallagher for their comments and suggestions, as well as to the board and staff of the Lauterpacht Research Centre for Inter- national Law at the University of Cambridge for their hospitality during the period I worked there on this article. -

From Charlemagne to Hitler: the Imperial Crown of the Holy Roman Empire and Its Symbolism

From Charlemagne to Hitler: The Imperial Crown of the Holy Roman Empire and its Symbolism Dagmar Paulus (University College London) [email protected] 2 The fabled Imperial Crown of the Holy Roman Empire is a striking visual image of political power whose symbolism influenced political discourse in the German-speaking lands over centuries. Together with other artefacts such as the Holy Lance or the Imperial Orb and Sword, the crown was part of the so-called Imperial Regalia, a collection of sacred objects that connotated royal authority and which were used at the coronations of kings and emperors during the Middle Ages and beyond. But even after the end of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806, the crown remained a powerful political symbol. In Germany, it was seen as the very embodiment of the Reichsidee, the concept or notion of the German Empire, which shaped the political landscape of Germany right up to National Socialism. In this paper, I will first present the crown itself as well as the political and religious connotations it carries. I will then move on to demonstrate how its symbolism was appropriated during the Second German Empire from 1871 onwards, and later by the Nazis in the so-called Third Reich, in order to legitimise political authority. I The crown, as part of the Regalia, had a symbolic and representational function that can be difficult for us to imagine today. On the one hand, it stood of course for royal authority. During coronations, the Regalia marked and established the transfer of authority from one ruler to his successor, ensuring continuity amidst the change that took place. -

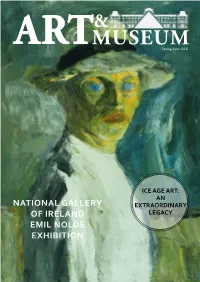

MUSEUM ART Spring Issue 2018

& MUSEUM ART Spring Issue 2018 ICE AGE ART: AN NATIONAL GALLERY EXTRAORDINARY OF IRELAND LEGACY EMIL NOLDE EXHIBITION CONTENTS 12 ANGELA ROSENGART 14 Interview with Madam Rosengarth about the Rosengarth Museum IVOR DAVIES Inner Voice of the Art World 04 18 NATIONAL GALLERY OF IRELAND SCULPTOR DAWN ROWLAND Sean Rainbird CEO & Editor Director National Gallery of Ireland Siruli Studio WELCOME Interviewed by Pandora Mather-Lees Interview with Derek Culley COVER IMAGE Emil Nolde (1867-1956) Self-portrait, 1917 ART & MUSEUM Magazine and will also appear at many of Selbstbild, 1917 Oil on plywood, 83.5 x 65 cm MAGAZINE the largest finance, banking and Family © Nolde Stiftung Seebüll Office Events around the World. Welcome to Art & Museum Magazine. This Media Kit. - www.ourmediakit.co.uk publication is a supplement for Family Office Magazine, the only publication in the world We recently formed several strategic dedicated to the Family Office space. We have partnerships with organisations including a readership of over 46,000 comprising of some The British Art Fair and Russian Art of the wealthiest people in the world and their Week. Prior to this we have attended and advisors. Many have a keen interest in the arts, covered many other international art fairs some are connoisseurs and other are investors. and exhibitions for our other publications. Many people do not understand the role of We are very receptive to new ideas for a Family Office. This is traditionally a private stories and editorials. We understand wealth management office that handles the that one person’s art is another person’s investments, governance and legal regulation poison, and this is one of the many ideas for a wealthy family, typically those with over we will explore in the upcoming issues of £100m + in assets. -

The King, the Crown and the Colonel: How Did Thomas Blood Try to Steal the Crown Jewels in 1671?

Education Service The king, the crown and the colonel: How did Thomas Blood try to steal the crown jewels in 1671? This resource was produced using documents from the collections of The National Archives. It can be freely modified and reproduced for use in the classroom only. The king, the crown and the colonel : How did Thomas Blood try to steal the crown jewels in 1671? 2 Introduction After the execution of Charles I in 1649 many of the crown jewels were sold or destroyed. Oliver Cromwell ordered that the orb and sceptres should be broken as they stood for the 'detestable rule of kings'. All the gemstones were removed and sold and the precious metal was used to make coins. When the monarchy was restored in 1660, two new sceptres and an orb costing £12,185 were made for the coronation of Charles II in 1661. Can you spot any of these items in the picture at the top of this page? During the ceremony, the new king held the Sceptre with the Cross in his right hand and the Sceptre with the Dove in his left. The sceptre was a rod or staff which represents royal power and the dove refers to the Holy Spirit. The king was crowned with St Edward's Crown. At some point the king also held the orb, a hollow golden sphere decorated with a band of jewels and a jewelled cross on top. The orb refers to the king’s role as protector of the church. Charles II allowed the crown jewels to be shown to members of the public for a viewing fee paid to a custodian (keeper) who looked after the jewels in the Martin Tower at the Tower of London. -

PDF EN Für Web Ganz

MUNICH MOZART´S STAY The life and work of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart is closely connected to Munich, a centre of the German music patronage. Two of his most famous works Mozart composed in the residence city of Munich: On the 13th January, 1775 the premiere from „La finta giardinera “took place, on the 29th January, 1781 the opera "Idomeneo" was launched at Cuvilliés Theater. Already during his first trip at the age of six years Wolfgang played together with his sister Nannerl for Elector Maximilian Joseph III. The second visit followed a year later, in June, 1763. From Munich the Mozart family started to their three year European journey to Paris and London. On the way back from this triumphal journey they stopped in Munich again and Mozart gave concerts at the Emperors court. Main focus of the next trip to Munich (1774 – in 1775) was the premiere of the opera "La finta giardiniera" at the Salvatortheater. In 1777 when Wolfgang and his mother were on the way to Paris Munich was destination again and they stayed 14 days in the Isar city. Unfortunately, at that time Wolfgang aspired in vain to and permanent employment. Idomeneo, an opera which Mozart had composed by order of Elector Karl Theodor, was performed in Munich for the first time at the glamorous rococo theatre in the Munich palace, the Cuvilliés Theater. With pleasure he would have remained in Munich, however, there was, unfortunately, none „vacatur “for him again. In 1790 Mozart came for the last time to Munich on his trip to the coronation of Leopold II in Frankfurt. -

Volker Sellin European Monarchies from 1814 to 1906

Volker Sellin European Monarchies from 1814 to 1906 Volker Sellin European Monarchies from 1814 to 1906 A Century of Restorations Originally published as Das Jahrhundert der Restaurationen, 1814 bis 1906, Munich: De Gruyter Oldenbourg, 2014. Translated by Volker Sellin An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libra- ries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 License, as of February 23, 2017. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. ISBN 978-3-11-052177-1 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-052453-6 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-052209-9 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2017 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Cover Image: Louis-Philippe Crépin (1772–1851): Allégorie du retour des Bourbons le 24 avril 1814: Louis XVIII relevant la France de ses ruines. Musée national du Château de Versailles. bpk / RMN - Grand Palais / Christophe Fouin. Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck ♾ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Contents Introduction 1 France1814 8 Poland 1815 26 Germany 1818 –1848 44 Spain 1834 63 Italy 1848 83 Russia 1906 102 Conclusion 122 Bibliography 126 Index 139 Introduction In 1989,the world commemorated the outbreak of the French Revolution two hundred years earlier.The event was celebratedasthe breakthrough of popular sovereignty and modernconstitutionalism. -

Gender-Bending Regalia in the Tomb of Constance of Aragon, Queen of Hungary and Sicily

2018 V From Her Head to Her Toes: Gender-Bending Regalia in the Tomb of Constance of Aragon, Queen of Hungary and Sicily Christopher Mielke Article: From Her Head to Her Toes: Gender-Bending Regalia in the Tomb of Constance of Aragon, Queen of Hungary and Sicily From Her Head to Her Toes: Gender-Bending Regalia in the Tomb of Constance of Aragon, Queen of Hungary and Sicily Christopher Mielke INDEPENDENT SCHOLAR Abstract: This article re-examines József Deér’s claim that the crown uncovered in the tomb of Constance of Aragon (d. 1222) was originally her husband’s. His argument is based entirely on the shape of the crown itself, and ignores the context of her burial and the other idiosyncrasies of Frederick II’s burial provisions at Palermo Cathedral. By examining the contents of the grave of Constance, and by discussing patterns related to the size of medieval crowns recovered from archaeological context, the evidence indicates that this crown would have originally adorned the buried queen’s head. Rather than identifying it as a ‘male’ crown that found its way into the queen’s sarcophagus as a gift from her husband, this article argues that Constance’s crown is evidence that as a category of analysis, gender is not as simple as it may appear. In fact, medieval crowns often had multiple owners and sometimes a crown could be owned, or even worn, by someone who had a different gender than the original owner. This fact demonstrates the need for a more complex, nuanced interpretation of regalia found in an archaeological context. -

Download Detailed Coronation Crown Instructions and Templates

Getty at Home Coronation Crown A crown is often bestowed as part of the inaugural ceremony (coronation) of a king or a queen as a symbol of honor and regal status. Materials: • Primary: construction paper or card stock, crayons, colored pencils, markers, paints, brushes, scissors, glue, and template (provided). • Optional: stapler, glue gun, decorative stickers, glitter, sequins, tin foil, noodles, The Coronation of the Virgin (detail), cereal, lace, pom poms, pipe cleaners, Jean Bourdichon, about 1480-1490. or cut paper shapes. You can cut or hole punch elements from old greeting cards or wrapping paper for more decorative options. Use your imagination! • Alternative: paper bag, gift bag, flattened cereal box, lightweight cardboard, or foam sheets. Tips for starting: • Gather all materials beforehand. If you don’t have the exact materials, improvise! • Use sheets measuring 8½ x 11 inches or larger for tracing the template Completed coronation crowns • Print the custom Getty crown template. © 2020 J. Paul Getty Trust Getty at Home Coronation Crown Instructions: 1. Print custom Getty template and cut out the three crown segments. 2. Decorate the printed template directly with dry media (like crayons, markers, etc.) and lightweight decorations for best results. Decorating the crown template directly 3. Or, use the template to trace three crown segments on another material like construction paper, cardstock, or cardboard 4. Cut out traced segments and decorate with crayons, markers, paints, decorative stickers, glitter, sequins, tin foil, noodles, cereal, lace, pom poms, pipe cleaners, and/or cut paper shapes. Tracing the template onto another material 5. Glue or staple the three decorated crown segments together to make one long band. -

Country Coding Units

INSTITUTE Country Coding Units v11.1 - March 2021 Copyright © University of Gothenburg, V-Dem Institute All rights reserved Suggested citation: Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Staffan I. Lindberg, Jan Teorell, and Lisa Gastaldi. 2021. ”V-Dem Country Coding Units v11.1” Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project. Funders: We are very grateful for our funders’ support over the years, which has made this ven- ture possible. To learn more about our funders, please visit: https://www.v-dem.net/en/about/ funders/ For questions: [email protected] 1 Contents Suggested citation: . .1 1 Notes 7 1.1 ”Country” . .7 2 Africa 9 2.1 Central Africa . .9 2.1.1 Cameroon (108) . .9 2.1.2 Central African Republic (71) . .9 2.1.3 Chad (109) . .9 2.1.4 Democratic Republic of the Congo (111) . .9 2.1.5 Equatorial Guinea (160) . .9 2.1.6 Gabon (116) . .9 2.1.7 Republic of the Congo (112) . 10 2.1.8 Sao Tome and Principe (196) . 10 2.2 East/Horn of Africa . 10 2.2.1 Burundi (69) . 10 2.2.2 Comoros (153) . 10 2.2.3 Djibouti (113) . 10 2.2.4 Eritrea (115) . 10 2.2.5 Ethiopia (38) . 10 2.2.6 Kenya (40) . 11 2.2.7 Malawi (87) . 11 2.2.8 Mauritius (180) . 11 2.2.9 Rwanda (129) . 11 2.2.10 Seychelles (199) . 11 2.2.11 Somalia (130) . 11 2.2.12 Somaliland (139) . 11 2.2.13 South Sudan (32) . 11 2.2.14 Sudan (33) . -

The House of Coburg and Queen Victoria: a Study of Duty and Affection

University of Nebraska at Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Student Work 6-1-1971 The House of Coburg and Queen Victoria: A study of duty and affection Terrence Shellard University of Nebraska at Omaha Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork Recommended Citation Shellard, Terrence, "The House of Coburg and Queen Victoria: A study of duty and affection" (1971). Student Work. 413. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork/413 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Work by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE HOUSE OF COBURG AND QUEEN VICTORIA A STORY OF DUTY AND AFFECTION A Thesis Presented to the Department of History and the Faculty of the Graduate College University of Nebraska at Omaha In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by Terrance She Ha r d June Ip71 UMI Number: EP73051 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Diss««4afor. R_bJ .stung UMI EP73051 Published by ProQuest LLC (2015). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code ProQuest LLC.