The Memphis Sanitation Workers Strike Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sequence 01 2 Page 1 of 25 Cheryl Cotton, Cameron Norman, Obdieah Robinson

Sequence 01_2 Page 1 of 25 Cheryl Cotton, Cameron Norman, Obdieah Robinson [0:00:00] Cheryl Cotton: Good morning. I’m Cheryl Fanion Cotton and I want to read something that I wrote. Several years ago I was up and couldn’t sleep and I went to my computer feeling a little blue. And I said “Cheryl, why don’t you write down some of the things you’ve done in life.” So that’s what I did. So these are called the “I Haves Of My Life.” I have attended church all of my life. My church is here in South Memphis. Saint Mary United Methodist Church. I have loved and respected all of God’s creations. I have dutifully accepted servanthood as a way of life. I earned my high school diploma from Booker T. Washington high school in 1968. I grew up in the Civil Rights Movement and marched with Dr. King. I have pictures in the Ernest Withers Museum downtown and I looked for it last night and I just could not find it. I earned my college degree from the University of Pittsburgh in 1973. [0:01:00] I attended the school of theology at Boston University in 1974, where Dr. King earned his PhD. I attended Pittsburgh Theological Seminary from 1975-1978 and I earned a Masters Divinity Degree from Memphis Theological Seminary in 2000. I was a student chaplain at the old St. Joseph Hospital in Memphis and my job was to go around and pray in the rooms of patients. But I always asked for permission. -

Martin Luther King Jr.'S Mission and Its Meaning for America and the World

To the Mountaintop Martin Luther King Jr.’s Mission and Its Meaning for America and the World New Revised and Expanded Edition, 2018 Stewart Burns Cover and Photo Design Deborah Lee Schneer © 2018 by Stewart Burns CreateSpace, Charleston, South Carolina ISBN-13: 978-1985794450 ISBN-10: 1985794454 All Bob Fitch photos courtesy of Bob Fitch Photography Archive, Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries, reproduced with permission Dedication For my dear friend Dorothy F. Cotton (1930-2018), charismatic singer, courageous leader of citizenship education and nonviolent direct action For Reverend Dr. James H. Cone (1936-2018), giant of American theology, architect of Black Liberation Theology, hero and mentor To the memory of the seventeen high school students and staff slain in the Valentine Day massacre, February 2018, in Parkland, Florida, and to their families and friends. And to the memory of all other schoolchildren murdered by American social violence. Also by Stewart Burns Social Movements of the 1960s: Searching for Democracy A People’s Charter: The Pursuit of Rights in America (coauthor) Papers of Martin Luther King Jr., vol 3: Birth of a New Age (lead editor) Daybreak of Freedom: Montgomery Bus Boycott (editor) To the Mountaintop: Martin Luther King Jr.’s Mission to Save America (1955-1968) American Messiah (screenplay) Cosmic Companionship: Spirit Stories by Martin Luther King Jr. (editor) We Will Stand Here Till We Die Contents Moving Forward 9 Book I: Mighty Stream (1955-1959) 15 Book II: Middle Passage (1960-1966) 174 Photo Gallery: MLK and SCLC 1966-1968 376 Book III: Crossing to Jerusalem (1967-1968) 391 Afterword 559 Notes 565 Index 618 Acknowledgments 639 About the Author 642 Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, the preeminent Jewish theologian, introduced Martin Luther King Jr. -

HESCHEL-KING FESTIVAL Mishkan Shalom Synagogue January 4-5, 2013

THE HESCHEL-KING FESTIVAL Mishkan Shalom Synagogue January 4-5, 2013 “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. “In a free society, when evil is done, some are guilty, but all are responsible.” Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., fourth from right, walking alongside Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, second from right, in the Selma civil rights march on March 21, 1965 Table of Contents Welcome...3 Featured Speakers....10 General Information....4 Featured Artists....12 Program Schedule Community Groups....14 Friday....5 The Heschel-King Festival Saturday Morning....5 Volunteers....17 Saturday Afternoon....6 Financial Supporters....18 Saturday Evening....8 Community Sponsors....20 Mishkan Shalom is a Reconstructionist congregation in which a diverse community of progressive Jews finds a home. Mishkan’s Statement of Principles commits the community to integrate Prayer, Study and Tikkun Olam — the Jewish value for repair of the world. The synagogue, its members and Senior Rabbi Linda Holtzman are the driving force in the creation of this Festival. For more info: www.mishkan.org or call (215) 508-0226. 2 Welcome to the Heschel-King Festival Thank you for joining us for the inaugural Heschel-King Festival, a weekend of singing together, learning from each other, finding renewal and common ground, and encouraging one another’s action in the spirit of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel. Dr. King and Rabbi Heschel worked together in the battle for civil rights, social justice and peace. Heschel marched alongside King in Selma, Alabama, demanding voting rights for African Americans. -

"I AM a 1968 Memphis Sanitation MAN!": Race, Masculinity, and The

LaborHistory, Vol. 41, No. 2, 2000 ªIAMA MAN!º: Race,Masculinity, and the 1968 MemphisSanitation Strike STEVEESTES* On March 28, 1968 Martin LutherKing, Jr. directeda march ofthousands of African-American protestersdown Beale Street,one of the major commercial thoroughfares in Memphis,Tennessee. King’ splane had landedlate that morning, and thecrowd was already onthe verge ofcon¯ ict with thepolice whenhe and other members ofthe Southern Christian LeadershipConference (SCLC) took their places at thehead of the march. The marchers weredemonstrating their supportfor 1300 striking sanitation workers,many ofwhom wore placards that proclaimed, ªIAm a Man.ºAs the throng advanceddown Beale Street,some of the younger strike support- ersripped theprotest signs off the the wooden sticks that they carried. Theseyoung men,none of whomwere sanitation workers,used the sticks to smash glass storefronts onboth sidesof the street. Looting ledto violent police retaliation. Troopers lobbed tear gas into groups ofprotesters and sprayed mace at demonstratorsunlucky enough tobe in range. High above thefray in City Hall, Mayor HenryLoeb sat in his of®ce, con®dent that thestrike wasillegal, andthat law andorder wouldbe maintained in Memphis.1 This march wasthe latest engagement in a®ght that had raged in Memphissince the daysof slaveryÐ acon¯ict over African-American freedomsand civil rights. In one sense,the ª IAm aManºslogan wornby thesanitation workersrepresented a demand for recognition oftheir dignity andhumanity. This demandcaught whiteMemphians bysurprise,because they had always prided themselvesas being ªprogressiveºon racial issues.Token integration had quietly replaced public segregation in Memphisby the mid-1960s, butin the1967 mayoral elections,segregationist candidateHenry Loeb rodea waveof white backlash against racial ªmoderationºinto of®ce. -

A Summary of the Contributions of Four Key African American Female Figures of the Civil Rights Movement

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 12-1994 A Summary of the Contributions of Four Key African American Female Figures of the Civil Rights Movement Michelle Margaret Viera Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Viera, Michelle Margaret, "A Summary of the Contributions of Four Key African American Female Figures of the Civil Rights Movement" (1994). Master's Theses. 3834. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/3834 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A SUMMARY OF THE CONTRIBUTIONS OF FOUR KEY AFRICAN AMERICAN FEMALE FIGURES OF THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT by Michelle Margaret Viera A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of History Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan December 1994 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My appreciation is extended to several special people; without their support this thesis could not have become a reality. First, I am most grateful to Dr. Henry Davis, chair of my thesis committee, for his encouragement and sus tained interest in my scholarship. Second, I would like to thank the other members of the committee, Dr. Benjamin Wilson and Dr. Bruce Haight, profes sors at Western Michigan University. I am deeply indebted to Alice Lamar, who spent tireless hours editing and re-typing to ensure this project was completed. -

Women in the Movement

WOMEN IN THE MOVEMENT ESSENTIAL QUESTION ACTIVITIES How did women leaders influence the civil rights movement? 2 Do-Now: Opening Questions LESSON OVERVIEW 2 A Close View: In this lesson students will expand their historical understanding and appreciation Analyzing Images of women in the Civil Rights Movement, especially the role of Coretta Scott King as 3 Analyzing Film as Text a woman, mother, activist, and wife. Students also will learn about other women leaders in the movement through listening and analyzing first-person interviews 4 Close View of Interview from The Interview Archive. Threads Students will apply the historical reading skills of sourcing, contextualization, 5 Research: Corroboration and corroboration, and broaden their skills and use of close reading strategies by analyzing historical images, documentary film, and first-person interviews alongside 5 Closing Discussion Questions the transcript. As a demonstration of learning and/or assessment, students will 6 Homework or Extended write a persuasive essay expanding on their understanding of women in the Civil Learning Rights Movement through a writing prompt. Through this process students will continue to build upon the essential habits of a historian and establish a foundation for critical media literacy. HANDOUTS LESSON OBJECTIVES 7 Close View of the Film Students will use skills in reading history and increase their understanding of history, particularly of women in the Civil Rights Movement, by: 8 Women in the Movement: • Analyzing primary source materials including photographs and documents Interview Thread One • Critically viewing documentary film and first-person interviews to inform 10 Women in the Movement: their understanding of the lesson topic Interview Thread Two • Synthesizing new learning through developing questions for further historical inquiry • Demonstrating their understanding of the lesson topic through a final writing exercise MATERIALS • Equipment to project photographs • Equipment to watch video • Copies of handouts 1 ACTIVITIES 1. -

African American Civil Rights Grant Program

African American Civil Rights Grant Program - FY 2016 - FY 2018 Fiscal year Site/Project Name Organization City State Award Amount Project Summary Site Significance FY 2018 Edmund Pettus Bridge: Historic Structures Report Auburn University Auburn AL $50,000 FY 2018 Rehabilitation of St. Paul United Methodist Church St. Paul United Methodist Church Birmingham AL $500,000 FY 2018 Preservation and Rehabilitation of the Sixteenth Street Sixteenth Street Bapsit Church Birmingham AL $500,000 Baptist Church: Phase 3 FY 2018 Rehabilitation of the Historic Bethel Church Parsonage Historic Bethel Baptist Church Community Birmingham AL $258,209 Restoration Fund FY 2018 Stabilization and Roof Replacement of the Historic Lincolnite Club, Inc. Marion AL $500,000 Lincoln Normal School Gymnasium: Phase 1 FY 2018 Rehabilitation of the Historic Moore Building: Phase 2 Alabama Historical Commission Montgomery AL $500,000 FY 2018 Freedom Rides Museum Exhibit Plan Alabama Historical Commission Montgomery AL $50,000 FY 2018 Rehabilitation of the Amelia Boynton Residence Gateway Educational Foundation, Inc. & Brown Selma AL $500,000 Chapel AME Church FY 2018 Preservation of Historic Brown Chapel: Phase 3 Brown Chapel AME Historical Preservation Selma AL $500,000 Foundation FY 2018 Oral Histories of the Untold Tabernacle Story Tabernacle Baptist Church – Selma, AL Legacy Selma AL $37,950 Foundation, Inc. FY 2018 Tabernacle Baptist Church: Historic Structure Report and Tabernacle Baptist Church –Legacy Foundation, Selma AL $500,000 Stained Glass Assessment Inc. -

Scanned Using Book Scancenter 5131

An Unseen Li^ht Black Struggles for Freedom in Memphis, Tennessee Edited by Aram Goudsouzian and Charles W. McKinney Jr. UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY “Since I Was a Citizen, I Had the Bight to Attend the Library” The Key Role of the Public Library in the Civil Rights Movement in Memphis Steven A. Knowlton Memphian Jesse Turner, an African American, wanted his wife to be able to use the library. Throughout the winter of 1949 Allegra Turner was in mourning for a younger brother who had been killed in a railroad accident. Looking for a diversion, Jesse Turner suggested that a visit to the library might help Mrs. Turner “become engrossed in both fun and facts.Mr. Turner, an officer at the Tri-State Bank located just a few blocks from the Cossitt Library on Front Street, had used the Memphis Public Library’s main branch (named for its benefactor, Frederick Cos sitt) in the past. Crucially, he had never sat down or tried to borrow a book. Due to a quirk in the rules of segregation, Jesse Turner had been allowed to stand in the reference section while he looked up a few facts in a book. Had he attempted to use the fuU range of the hbrary’s facilities, he would have known better than to suggest that Mrs. Turner would be welcome at the Cossitt Library downtown. i Her travails that day encapsulate the eyeryday realities of African American life in segregated Memphis. Allegra Turner, who was familiar with the workings of libraries from her days as a student and instructor at Southern University and the University of Chicago, entered the library and made straight for the card catalog. -

Marching Across the Putative Black/White Race Line: a Convergence of Narratology, History, and Theory Carol L

Boston College Journal of Law & Social Justice Volume 33 | Issue 2 Article 2 May 2013 Marching Across the Putative Black/White Race Line: A Convergence of Narratology, History, and Theory Carol L. Zeiner St. Thomas University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/jlsj Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Legal History Commons, United States History Commons, and the Women's History Commons Recommended Citation Carol L. Zeiner, Marching Across the Putative Black/White Race Line: A Convergence of Narratology, History, and Theory, 33 B.C.J.L. & Soc. Just. 249 (2013), http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/jlsj/vol33/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Journal of Law & Social Justice by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MARCHING ACROSS THE PUTATIVE BLACK/WHITE RACE LINE: A CONVERGENCE OF NARRATOLOGY, HISTORY, AND THEORY Carol L. Zeiner* Abstract: This Article introduces a category of women who, until now, have been omitted from the scholarly literature on the civil rights move- ment: northern white women who lived in the South and became active in the civil rights movement, while intending to continue to live in the South on a permanent basis following their activism. Prior to their activ- ism, these women may have been viewed with suspicion because they were “newcomers” and “outsiders.” Their activism earned them the pejorative label “civil rights supporter.” This Article presents the stories of two such women. -

Civil Rights Done Right a Tool for Teaching the Movement TEACHING TOLERANCE

Civil Rights Done Right A Tool for Teaching the Movement TEACHING TOLERANCE Table of Contents Introduction 2 STEP ONE Self Assessment 3 Lesson Inventory 4 Pre-Teaching Reflection 5 STEP TWO The "What" of Teaching the Movement 6 Essential Content Coverage 7 Essential Content Coverage Sample 8 Essential Content Areas 9 Essential Content Checklist 10 Essential Content Suggestions 12 STEP THREE The "How" of Teaching the Movement 14 Implementing the Five Essential Practices 15 Implementing the Five Essential Practices Sample 16 Essential Practices Checklist 17 STEP FOUR Planning for Teaching the Movement 18 Instructional Matrix, Section 1 19 Instructional Matrix, Section 1 Sample 23 Instructional Matrix, Section 2 27 Instructional Matrix, Section 2 Sample 30 STEP FIVE Teaching the Movement 33 Post-Teaching Reflection 34 Quick Reference Guide 35 © 2016 Teaching Tolerance CIVIL RIGHTS DONE RIGHT // 1 TEACHING TOLERANCE Civil Rights Done Right A Tool for Teaching the Movement Not long ago, Teaching Tolerance issued Teaching the Movement, a report evaluating how well social studies standards in all 50 states support teaching about the modern civil rights movement. Our report showed that few states emphasize the movement or provide classroom support for teaching this history effectively. We followed up these findings by releasingThe March Continues: Five Essential Practices for Teaching the Civil Rights Movement, a set of guiding principles for educators who want to improve upon the simplified King-and-Parks-centered narrative many state standards offer. Those essential practices are: 1. Educate for empowerment. 2. Know how to talk about race. 3. Capture the unseen. 4. Resist telling a simple story. -

Black Women's Music Database

By Stephanie Y. Evans & Stephanie Shonekan Black Women’s Music Database chronicles over 600 Africana singers, songwriters, composers, and musicians from around the world. The database was created by Dr. Stephanie Evans, a professor of Black women’s studies (intellectual history) and developed in collaboration with Dr. Stephanie Shonekon, a professor of Black studies and music (ethnomusicology). Together, with support from top music scholars, the Stephanies established this project to encourage interdisciplinary research, expand creative production, facilitate community building and, most importantly, to recognize and support Black women’s creative genius. This database will be useful for music scholars and ethnomusicologists, music historians, and contemporary performers, as well as general audiences and music therapists. Music heals. The purpose of the Black Women’s Music Database research collective is to amplify voices of singers, musicians, and scholars by encouraging public appreciation, study, practice, performance, and publication, that centers Black women’s experiences, knowledge, and perspectives. This project maps leading Black women artists in multiple genres of music, including gospel, blues, classical, jazz, R & B, soul, opera, theater, rock-n-roll, disco, hip hop, salsa, Afro- beat, bossa nova, soka, and more. Study of African American music is now well established. Beginning with publications like The Music of Black Americans by Eileen Southern (1971) and African American Music by Mellonee Burnim and Portia Maultsby (2006), -

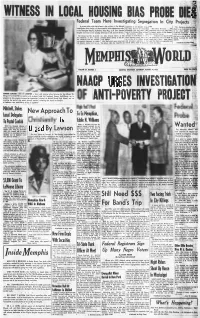

Insidememphis

Federal Team Here Investigating Segregation In City Projects i A person who might have been a key witness in the federal apartment in the Memphis Hous that: “Mrs. McClaren requested that’I investigation Into charges of discrimination and segregation with ing setup because an expanding " Mrs. Marie McClaren .... has check to see if she could be housed in the Memphis Housing Authority died Aug. 2 at John Gdston automobile firm was taking ovtr made daily calls to this office (Dix in any other project, preferably Hospital and was buried Sunday afternoon in Mt Carmel Annex. land at the Ashland Street address. ie Homes) relative to her immed Lauderdale Court (all - whit«>,4t Mrs. .Cornelia Crenshaw, then iate need for housing. is her wish to remain In the htjft The witness was Mrs. Marie Ed ter, Mrs. Georgia Morris, at 205 manager of Dixie Homes, an all - “.. I informed her that we have pital area as she is under consta# dins McClaren of 337-C Decatur, Ashland before moving to the De Negro housing project, sent a let no vacancy nor notice of intent to clinical treatment for cancer itti Mrs. McClaren, who was undergo catur address. ter to Miss E. C. Wilson, leasing vacate on a three - room apart diabetes. ing constant treatment for cancer Mrs. McClaren's name came Into and occupancy supervisor at the ment for which her application was il ■ $ |s ■ and diabetes, resided with iiet sis- the picture when she requested an central office, June 9, explaining issued for rental. (Continued on Page IWt) ■ 1®i st sjg!FW ¡■Sì Z Al Memphi.„ fn i W 5, VOLUME 34, NUMBER 6 MEMPHIS, TENNESSEE, SATURDAY, AUGUST 14, 1965 4.- NAACP ES INVE 3 SUMMER SCHOOL'S LeMOYNE - Mrs.