Diversity & Inclusion in Motorsport

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

First Lady of Le Mans

FIA WOMEN IN MOTOR SPORT OFFICIAL NEWSLETTER - ISSUE 3 MARÍA REMEMBERED Payinging tribute to the remarkable and inspirational María de Villota PG 4 AUTO SHOOTOUT SUCCESS Lucile Cypriano becomes Commission’s selected driver in VW Scirocco R-Cup PG 8 WOMEN IN WOMEN’S RALLYING POINT The FIA European Rallycross Championship has become a haven for lady racers PG 14 MOTORSPORT FIRST LADY OF LE MANS New FIA Women in Motorsport Commission Ambassador Leena Gade on progress, pressure and winning in the WEC AUTO+WOMEN IN MOTOR SPORT AUTO+WOMEN IN MOTOR SPORT Welcome to our third Women in Motorsport newsletter and the final edition of 2013. It’s been a year of both triumph and, unfortunately, tragedy and in this issue we take time out to remember María de Villota, whose passing in October left a deep void not just in motor sport but in all our hearts. María’s bravery following her F1 testing accident and the dedication she displayed afterwards – not only in promoting female involvement in motor sport but also safety on the road and track – will be missed. Elsewhere, it was a year of great success for women competitors and in this edition we look at Lucile Cypriano’s victory in the VW and commission-supported shoot-out for a place in next year’s VW Scirocco R-Cup and reveal how the FIA European Rallycross Championship has become a haven for female racers. It’s been a great year for CONTACTS: women in all forms of motor sport and IF YOU HAVE ANY COMMENTS ABOUT THIS NEWSLETTER OR we look forward to even more in 2014! STORIES FOR THE NEXT ISSUE, WE WOULD LOVE TO HEAR FROM YOU. -

CALIFORNIA RALLY SERIES 2015 RULES and RALLY HANDBOOK

CALIFORNIA RALLY SERIES 2015 RULES and RALLY HANDBOOK TABLE OF CONTENTS GETTING STARTED IN RALLYING 2 VEHICLE ELIGIBILITY 12 CRS CHARTER 13 CRS BOG 13 EVENT REQUIREMENTS and SUPPORT 14 CRS MEMBERSHIP 16 CRS RALLY CHAMPIONSHIP 17 CRS RALLYSPRINT CHAMPIONSHIP 17 CRS RALLYCROSS CHAMPIONSHIP 19 2015 CRS CALENDARS 22 COMMON CHAMPIONSHIP INFO 24 YEAR END AWARDS 26 APPENDIXES A) PERFORMANCE STOCK CLASS RULES 27 B) CRS OPEN LITE CLASS RULES 32 C) CRS OPEN & CRS-2 CLASS RULES 33 D) PREVIOUS RALLY CHAMPIONS 33 E) PREVIOUS RALLYSPRINT CHAMPIONS 38 F) PREVIOUS CRS MOTO CHAMPIONS 38 G) PREVIOUS RALLYCROSS CHAMPIONS 38 H) SPECIAL AWARD WINNERS 40 I) 2014 AWARD WINNERS 42 J) 2015 CRS OFFICERS 44 Check Out: www.CaliforniaRallySeries.com 1 WELCOME TO PERFORMANCE RALLYING ! To a rally driver it’s an all out, day or night race on an unknown dirt road, trying by sheer concentration to blend a high-strung, production based race car and the road into an unbeatable stage time. To a co-driver it’s the thrill of the world’s greatest amusement park ride, combined with the challenge of performing with great mental accuracy under the most physi- cally demanding conditions. For the spectator it’s a view of the most exciting and demanding of motor sports. Around the world, rallying is wildly popular, attracting huge crowds that line the roads at every event in the FIA World Rally Championship. In a performance rally, each team consists of a driver and co-driver (navigator). The cars start at one or two-minute intervals and race at top speed against the clock over competition stages. -

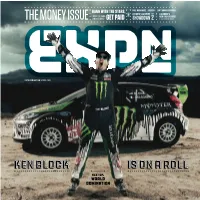

KEN BLOCK Is on a Roll Is on a Roll Ken Block

PAUL RODRIGUEZ / FRENDS / LYN-Z ADAMS HAWKINS HANG WITH THE STARS, PART lus OLYMPIC HALFPIPE A SLEDDER’S (TRAVIS PASTRANA, P NEW ENERGY DRINK THE MONEY ISSUE JAMES STEWART) GET PAID SHOWDOWN 2 IT’S A SHOCKER! PAGE 8 ESPN.COM/ACTION SPRING 2010 KENKEN BLOCKBLOCK IS ON A RROLLoll NEXT UP: WORLD DOMINATION SPRING 2010 X SPOT 14 THE FAST LIFE 30 PAY? CHECK. Ken Block revolutionized the sneaker Don’t have the board skills to pay the 6 MAJOR GRIND game. Is the DC Shoes exec-turned- bills? You can make an action living Clint Walker and Pat Duffy race car driver about to take over the anyway, like these four tradesmen. rally world, too? 8 ENERGIZE ME BY ALYSSA ROENIGK 34 3BR, 2BA, SHREDDABLE POOL Garth Kaufman Yes, foreclosed properties are bad for NOW ON ESPN.COM/ACTION 9 FLIP THE SCRIPT 20 MOVE AND SHAKE the neighborhood. But they’re rare gems SPRING GEAR GUIDE Brady Dollarhide Big air meets big business! These for resourceful BMXer Dean Dickinson. ’Tis the season for bikinis, boards and bikes. action stars have side hustles that BY CARMEN RENEE THOMPSON 10 FOR LOVE OR THE GAME Elena Hight, Greg Bretz and Louie Vito are about to blow. FMX GOES GLOBAL 36 ON THE FLY: DARIA WERBOWY Freestyle moto was born in the U.S., but riders now want to rule MAKE-OUT LIST 26 HIGHER LEARNING The supermodel shreds deep powder, the world. Harley Clifford and Freeskier Grete Eliassen hits the books hangs with Shaun White and mentors Lyn-Z Adams Hawkins BOBBY BROWN’S BIG BREAK as hard as she charges on the slopes. -

Los Costos Y La Logística Para El Mundial De Rally

Lunes 29 de octubre de 2018, Región del Bío Bío, N°3795, año XI $200 CONCEPCIÓN RECIBIRÁ SEXTA FECHA DEL EVENTO EN 2019 Los costos y la FOTO:ISIDORO VALENZUELA M. logística para el Mundial de Rally Autoridades y expertos analizaron impacto del evento. Tras el anuncio que Concepción será realizará el 12 de mayo. dos. Se espera que arriben mínimo 100 una de las sedes del Mundial de Rally Su costo aproximado sería de 9,6 mil personas, y capacidad hotelera ya 2019, viene lo más importante: prepa- millones de euros, los cuales serán está casi copada para la fecha. En 25 rar todo para el gran evento, que se financiados en gran medida por priva- días se conocerían las rutas. TD PÁGS. 6-7 FOTO.LUKAS JARA M. Noel Gallagher llegó para su concierto de mañana en Concepción TD PÁG. 15 FOTO: LUKAS JARA M. Balonmano de Adicpa se apresta a definir finalistas Luego de un semestre con partidos de alto nivel, en los próximos días, el Colegio Salesiano recibirá las semifinales en las categorías Infantil y Cadete. TD PÁGS. 10-11 Un talento que lleva Dos mil personas en corrida de colegios Almondale este deporte en la sangre Establecimientos organizaron la cuarta edición de su Corrida Familiar por el Medio Ambiente, que en esta ocasión tuvo un ingrediente especial: celebrar los 25 años de esta comunidad educativa. La cita, que se llevó a cabo en el Para Francisca Umaña, el hándbol parecía un destino, Parque Bicentenario, tuvo recorridos de 2, 5 y 10 kilómetros. TD PÁG. 5 pues sus padres y hermanos están ligados a la disciplina. -

*Lu Sulgh Vdyhg Iurp Ihhw Ghhs Soxqjh

RNI Regn. No. MPENG/2004/13703, Regd. No. L-2/BPLON/41/2006-2008 the death toll in ceasefire vio- lations by Pakistan in the twin districts of Poonch and Rajouri ith security forces going since July to eight — six sol- Wall out to target the diers and two civilians. Pakistan-backed terrorists in Meanwhile, with tensions Jammu & Kashmir, Islamabad rising along the LoC amid has resorted to uninterrupted repeated ceasefire violations, ceasefire violations through the Indian Army has launched the years to keep the Kashmir a fresh drive to reactivate Village pot boiling. The Pakistani Defence Committees (VDCs) in Army has committed more the forward areas of frontier than 2,050 unprovoked cease- Rajouri and Poonch districts. aryana Chief Minister fire violations this year in The objective is to improve HManohar Lal on Sunday which 21 Indians have been human intelligence and revive said the National Register of killed, the Ministry of External most of the defunct committees Citizens (NRC) would be Affairs said on Sunday. to effectively deal with the implemented in the State. “We have highlighted our fresh threat emanating from “In Haryana, we will imple- concerns at unprovoked cease- across the LoC. ment NRC along the lines of He met them under his would also be used in the fire violations by Pakistan “Village Defence Assam,” the Chief Minister party’s “Maha Sampark NRC, he added. forces, including in support of Committee training organised said while talking to the medi- Abhiyan” ahead of the State Manohar Lal had previ- cross-border terrorist infiltra- at Naoshera to refresh their apersons after meeting Justice Assembly polls in October. -

Yearbook Four 2017 Our Fourth Hyundai Motorsport Yearbook Explores the Growth and Milestones of Our Company During Another Exciting Year

Yearbook Four 2017 Our fourth Hyundai Motorsport Yearbook explores the growth and milestones of our company during another exciting year. With new World Rally Championship (WRC) regulations, it was a challenging 12 months that provided some of the most thrilling competition of the modern era. Our new car, the Hyundai i20 Coupe WRC, was a winning package on every surface and kept audiences transfixed on a championship battle that went all the way to the penultimate round… In 2017, we also branched out with our Customer Racing initiatives and welcomed a new circuit racer to our car line- up. The i30 N TCR joined the New Generation i20 R5 rally offering as part of our expanding customer activities. All this, and much more, is explored within these covers. Turn the pages for a candid look through each month from Monte-Carlo to Australia and join us in reflecting on Hyundai Motorsport’s fourth year in the world’s toughest motorsport championship. Hyundai Motorsport Yearbook Edition Four 2017 1 2 3 4 Contents WRC’s new era 06 July Launch of the i20 Coupe WRC 10 WRC Rally Finland 66 January i30 N performance 70 WRC Rally Monte-Carlo 16 Eifel Rallye Festival 74 February August WRC Rally Sweden 20 WRC Rally Germany 76 March September WRC Rally Mexico 24 Andreas Mikkelsen 80 Rallye Sanremo 28 R5 title successes 82 Marketing & PR Conference 32 HMDP 84 April October WRC Rally France 36 WRC Rally Spain 86 A car for all seasons 40 WRC Rally GB 90 WRC Rally Argentina 46 November May WRC Rally Australia 94 WRC Rally Portugal 50 i30 N TCR 98 June December WRC Rally Italy 54 Season review 104 WRC Rally Poland 58 Timeline 106 Ypres Rally 62 Partners 110 Thank you 116 Copyright: Hyundai Motorsport GmbH Publication: December 2017, All Rights Reserved. -

The Sprocket Geordie Chapter #9721

THE SPROCKET 2021, summer GEORDIE CHAPTER #9721 sponsoring dealer:Gateshead Harley-Davidson Welcome to the summer edition of The Sprocket What's in this issue: Barry says ... Letter from the Editor Head Road Captain Merchandise Officer Historian - all our yesteryears! Newbie Ride Activities and Events Ladies of Harley 2021, summer Opus Focus Indigestion Challenge Heart ‘n’ Soul Rally Seasoned campaigners … ! Snowdonia Wild Hogs Florida tales Pizza or pasta ... HAMC Poker Run Blast from the Past Geordie Chapter website Unity Ride Wordsearch Last words Thanks to Chris Neal for the cover photo! THE SPROCKET GEORDIE CHAPTER #9721 The Sprocket 2021, summer Barry says … Hello everyone, welcome to the second edition of our newsletter for 2021! When I sit back and think about the Chapter, I often think about the past, the great times I have experienced with you all – both on the road and at social events – and then I look forward and wonder what the future will hold for us all. My priority has always been you, our members, because without you this Chapter would not exist. I still get excited that through these difficult times we are still managing to attract new members into our group. As I write this I’m pleased to say that number is 27. That alone tells me we are still heading in the right direction. The camaraderie in our Chapter is on a very high level and that keeps me happy! Like I said in the previous newsletter, 2020 and the first part of 2021 has been the most challenging for me and the Committee but we can at last, I hope, finally see some sort of easing with the restrictions that we have to follow. -

MSA Stage Rally Safety Requirements

Edition 4 Stage Rally Safety Requirements ©2015-2018 Motorsport UK SRSRs April 2018 edition 4.docx 1 Motorsport UK Stage Rally Safety Requirements CONTENTS THE REQUIREMENTS ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 4 1. KEY ELEMENTS OF SAFETY PLANS INCLUDING ROLES AND REPONSIBILITIES ------------------------------------------ 4 1.2. The Safety Plan --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 4 1.5. The Incident Management Plan --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 5 1.7. A Suggested Contents List for Safety Plans -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 5 2. ROLES AND RESPONSIBILITIES ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 5 2.3. The Motorsport UK Safety Delegate ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 5 2.4. The Motorsport UK Steward ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 6 2.5. The Clerk of the Course ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 6 2.6. Scrutineers -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 7 SENIOR OFFICIALS ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ -

MATCHING SPORTS EVENTS and HOSTS Published April 2013 © 2013 Sportbusiness Group All Rights Reserved

THE BID BOOK MATCHING SPORTS EVENTS AND HOSTS Published April 2013 © 2013 SportBusiness Group All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the permission of the publisher. The information contained in this publication is believed to be correct at the time of going to press. While care has been taken to ensure that the information is accurate, the publishers can accept no responsibility for any errors or omissions or for changes to the details given. Readers are cautioned that forward-looking statements including forecasts are not guarantees of future performance or results and involve risks and uncertainties that cannot be predicted or quantified and, consequently, the actual performance of companies mentioned in this report and the industry as a whole may differ materially from those expressed or implied by such forward-looking statements. Author: David Walmsley Publisher: Philip Savage Cover design: Character Design Images: Getty Images Typesetting: Character Design Production: Craig Young Published by SportBusiness Group SportBusiness Group is a trading name of SBG Companies Ltd a wholly- owned subsidiary of Electric Word plc Registered office: 33-41 Dallington Street, London EC1V 0BB Tel. +44 (0)207 954 3515 Fax. +44 (0)207 954 3511 Registered number: 3934419 THE BID BOOK MATCHING SPORTS EVENTS AND HOSTS Author: David Walmsley THE BID BOOK MATCHING SPORTS EVENTS AND HOSTS -

Fia Junior Wrc Championship 2020 Announcement 2

FIA JUNIOR WRC CHAMPIONSHIP 2020 ANNOUNCEMENT 2 FOREWORD M-SPORT MANAGING DIRECTOR, MALCOLM WILSON OBE The FIA Junior WRC Championship is the most cost-effective way for any budding young driver to get onto the world stage. It’s a completely level playing field as every driver uses identical machinery, so it is very easy to measure yourself and FOREWORD your performance against other competitors. And it’s also a great way for young drivers to gain vital experience of WRC events. So many of the best rally drivers in the world have graduated from the Junior WRC, and many also have strong connections with M-Sport. We take great pride in working with young drivers and getting them where they need to be, and I think that’s a key reason why M-Sport Poland and Junior WRC are such a good match. CHAMPIONSHIP | FIA JUNIOR WRC We’ve worked hard with Ford to ensure that there is a clear ‘Ladder of Opportunity’ through which the most promising drvers can progress and having the all-new Ford Fiesta R2 as the car of choice for this year’s Junior WRC only strengthens that commitment. We are very proud of this car and also very proud of this championship; and I’m looking forward to seeing what the class of 2020 has to offer. 3 THE CHAMPIONSHIP The FIA Junior WRC Championship is the sport’s ultra-com- petitive entry-level series, giving rally stars of the future an opportunity to climb WRC’s ladder of opportunity. The Junior WRC is organised and promoted by M-Sport Poland and works with its key partners Pirelli and Wolf Lubricants to CHAMPIONSHIP CHAMPIONSHIP deliver the highest qualty equipment for affordable and accessible competition. -

Motorsport News

Motorsport News International Edition – April 2019 Romania FUCHS sponsors Valentin Dobre in 2019 Under Managing Director Camelia Popa, FUCHS Romania joins Valentin Dobre in the Romania Hill Climb Championship. These very popular races attract numerous visitors and are broadcast by Romanian Television. // Page 3. Portugal FUCHS develops a new partnership with Teodósio Motorsport team Ricardo Teodósio and co-driver José Teixeira of the Teodósio Motorsport team represent FUCHS in the Portugal Rally Championship with a Škoda Fabia R5. The Teodósio team win their first race of the PRC, followed by three stage podiums in the FIA ERC, proving themselves worthy competitors and claiming the 2019 title. // Page 7. Spain FUCHS official partner of Yamaha R1 Cup Mario Castillejo, FUCHS Automotive Director, signs a sponsorship deal with Yamaha Motor Sport for the second edition of the Yamaha R1 Cup. In this series 23 drivers compete in six races on the most renowned tracks in Spain; a great business strategy for FUCHS. // Page 12. www.fuchs.com/group Motorsport News International Edition – April 2019 South Africa Scribante succeeds at Zwartkops Coming off a disappointing second round of the G&H Transport Series race in Cape Town, the Franco Scribante Racing team put in some hard work and made a few mechanical tweaks to their Porsche 997 Turbo in preparation for round 3 which took place at Zwartkops Raceway. A rain drenched track didn’t stop FUCHS sponsored Franco Scribante from asserting his dominance, winning round 3 of the Supercar Series. Scribante was quick to demonstrate his intentions in the qualifying race, claiming pole position. -

SCCA Rallycross Rules (RXR) Supersedes Previous Editions of the SCCA Rallycross Rules

RULES 2015 Edition Sports Car Club of America®, Inc. 6620 SE Dwight St Topeka, Kansas 66619 1-800-770-2055 www.scca.com [email protected] Copyright © 2015 by the Sports Car Club of America®. All Rights reserved. Except as permitted under the United States Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Tenth printing July 2015 Revised July 8, 2015 Published by: Sports Car Club of America®, Inc. 6620 SE Dwight St Topeka, Kansas 66619 Copies may be ordered from: SCCA Properties 6620 SE Dwight St Topeka, Kansas 66619 1-800-770-2055 July 8, 2015 FOREWORD Effective January 1, 2015, the following SCCA RallyCross Rules (RXR) supersedes previous editions of the SCCA RallyCross Rules. The SCCA reserves the right to revise these Rules, to issue supplements to them, and publish special rules at any time at its sole discretion. Changes of this nature will normally become effective upon publication in Fastrack on the official SCCA website; but may become effective immediately in emergency situations as determined by SCCA. All correspondence should be addressed to: SCCA RallyCross Board, 6620 SE Dwight St, Topeka, KS 66619. E-mail submissions may be made to [email protected]. Questions concerning RallyCross Rules clarifications should be addressed to: SCCA RallyCross Board, C/O Rally Department, 6620 SE Dwight St, Topeka, Kansas 66619. E-mail submissions may be made to [email protected].