Little Beaver Creek Study Report, Ohio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Agenda Title Page

BEAVER LOCAL BOARD OF EDUCATION. BOARD MINUTES 2010 January 11, 2010 – Organizational/Regular Meeting The Beaver Local Board of Education met in organization/regular session on Monday, January 11, 2010, at 7:00 P.M., in the Beaver Local High School Media Center. Action on agenda items for the regular section of the meeting was preceded by a work session open to the public. ATTENDANCE BOARD MEMBERS: OTHERS: Mr. Buchheit Dr. DiBacco, Superintendent Mr. Garn Mr. Barrett, Treasurer Mr. McKenzie Administrators and Supervisors Mr. Wolfe Other interested and concerned Dr. Meredith citizens and employees CALL TO ORDER The meeting was called to order by the 2009 Board President, Dr. Meredith. The Pledge of Allegiance was recited in unison. The roll was called noting all members were present. ORGANIZATIONAL SECTION OF MEETING M-10.01 OATH OF OFFICE The Treasurer administered the Oath of Office to newly elected Board members Mr. Brad Buchheit and Mr. Thomas Wolfe (Exh. 10-1). M-10.02 ELECTION OF BOARD PRESIDENT Mr. McKenzie nominated Dr. Meredith to serve as President for 2010. Mr. Garn moved, seconded by Mr. Wolfe, to close nominations. Roll Call: Mr. Garn, yes; Mr. Wolfe, yes; Mr. Buchheit, yes; Mr. McKenzie, yes; Dr. Meredith, yes. Motion approved. Dr. Meredith elected as President of the Board for 2010. M-10.03 ELECTION OF BOARD VICE-PRESIDENT Mr. Buchheit nominated Mr. Wolfe to serve as Vice-President for 2010. Mr. McKenzie moved, seconded by Mr. Garn, to close nominations. Roll Call: Mr. McKenzie, yes; Mr. Garn, yes; Mr. Buchheit, yes; Mr. Wolfe, yes; Dr. -

Page 1 03089500 Mill Creek Near Berlin Center, Ohio 19.13 40.9638 80.9476 10.86 9.13 0.6880 58.17 0.77 0.41 2.10 03092000 Kale C

Table 2-1. Basin characteristics determined for selected streamgages in Ohio and adjacent States. [Characteristics listed in this table are described in detail in the text portion of appendix 2; column headings used in this table are shown in parentheses adjacent to the bolded long variable names] Station number Station name DASS Latc Longc SL10-85 LFPath SVI Agric Imperv OpenWater W 03089500 Mill Creek near Berlin Center, Ohio 19.13 40.9638 80.9476 10.86 9.13 0.6880 58.17 0.77 0.41 2.10 03092000 Kale Creek near Pricetown, Ohio 21.68 41.0908 81.0409 14.09 12.88 0.8076 40.46 1.08 0.48 2.31 03092090 West Branch Mahoning River near Ravenna, Ohio 21.81 41.2084 81.1983 20.23 11.19 0.5068 38.65 2.35 1.01 2.51 03102950 Pymatuning Creek at Kinsman, Ohio 96.62 41.4985 80.6401 5.46 21.10 0.6267 52.26 0.82 1.18 5.60 03109500 Little Beaver Creek near East Liverpool, Ohio 495.57 40.8103 80.6732 7.89 55.27 0.4812 38.05 1.98 0.79 1.41 03110000 Yellow Creek near Hammondsville, Ohio 147.22 40.5091 80.8855 9.37 33.62 0.5439 19.84 0.34 0.33 0.36 03111500 Short Creek near Dillonvale, Ohio 122.95 40.2454 80.8859 15.25 27.26 0.3795 30.19 1.08 0.93 1.16 03111548 Wheeling Creek below Blaine, Ohio 97.60 40.1274 80.9477 13.43 27.46 0.3280 40.92 0.97 0.56 0.64 03114000 Captina Creek at Armstrongs Mills, Ohio 133.69 39.9307 81.0696 13.56 26.99 0.6797 32.76 0.54 0.64 0.66 03115400 Little Muskingum River at Bloomfield, Ohio 209.94 39.6699 81.1370 5.50 44.84 0.7516 10.00 0.25 0.12 0.12 03115500 Little Muskingum River at Fay, Ohio 258.25 39.6406 81.1531 4.32 60.10 0.7834 -

Beaver Local School District Columbiana County Single

BEAVER LOCAL SCHOOL DISTRICT COLUMBIANA COUNTY TABLE OF CONTENTS TITLE PAGE Independent Auditor’s Report ....................................................................................................................... 1 Management’s Discussion and Analysis ....................................................................................................... 5 Statement of Net Position ........................................................................................................................... 15 Statement of Activities ................................................................................................................................. 16 Balance Sheet – Governmental Funds ....................................................................................................... 17 Reconciliation of Total Governmental Fund Balances to Net Position of Governmental Activities .................................................................................................. 18 Statement of Revenues, Expenditures and Changes in Fund Balances – Governmental Funds ............................................................................................................ 19 Reconciliation of the Statement of Revenues, Expenditures, and Changes in Fund Balances of Governmental Funds to the Statement of Activities ............................................................ 20 Statement of Revenues, Expenditures and Changes in Fund Balance – Budget (Non-GAAP Budgetary Basis) and Actual – General Fund ...................................... -

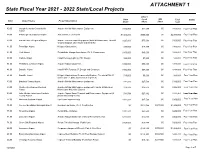

Current Aviation Projects

ATTACHMENT 1 State Fiscal Year 2021 - 2022 State/Local Projects Other / State Local MM Total Status BOA Airport Name Project Description Share Share Share Cost 80.00 Joseph A. Hardy Connellsville Acquire Airfield Maintenance Equipment $112,500 $37,500 $0 $150,000 Four Year Plan Airport 90.00 Pittsburgh International Airport Airfield Pavement Rehab $1,500,000 $500,000 $0 $2,000,000 Four Year Plan 89.00 Arnold Palmer Regional Airport Acquire Various Airport Equipment (Airfield Maintenance, Aircraft $225,000 $75,000 $0 $300,000 Four Year Plan Ground Support, Operations and Security) 84.00 Pennridge Airport Mitigate Obstructions $90,000 $10,000 $0 $100,000 Four Year Plan 84.00 York Airport Rehabilitate Hangar Area Apron, Ph. II: Construction $150,000 $50,000 $0 $200,000 Four Year Plan 83.00 Carlisle Airport Install Runway Lighting, Ph I: Design $22,500 $7,500 $0 $30,000 Four Year Plan 81.00 Wellsboro-Johnston Airport Acquire Airport Equipment $150,000 $50,000 $0 $200,000 Four Year Plan 81.00 Danville Airport Install PAPI Runway 27, Design and Construct $172,500 $57,500 $0 $230,000 Four Year Plan 81.00 Danville Airport Mitigate Obstructions, Permanently Displace Threshold RW 27 $45,000 $5,000 $0 $50,000 Four Year Plan (and repair / replace light fixtures or globes) 80.00 Bradford County Airport Acquire Airfield Maintenance Equipment $82,500 $27,500 $0 $110,000 Four Year Plan 80.00 Greater Breezewood Regional Acquire Airfield Maintenance Equipment (Tractor &Wide Area $76,875 $25,625 $0 $102,500 Four Year Plan Airport Mower) and Materials (Gravel) 80.00 John Murtha Johnstown-Cambria Acquire Airport Snow Removal and Maintenance Equipment (2 $83,588 $27,862 $0 $111,450 Four Year Plan County Airport plows and pickup trucks) 77.00 Hazleton Regional Airport Fuel Farm Improvements $112,500 $37,500 $0 $150,000 Four Year Plan 76.00 Pocono Mountains Municipal Airport Replace Fuel Farm, Ph. -

Se Ohio Sub-Area Spill Response Plan

SE OHIO SUB-AREA SPILL RESPONSE PLAN INITIAL INCIDENT ACTION PLAN (IAP) Version: May 17, 2016 Columbiana County Jefferson County Ohio Belmont County Monroe County This Initial Incident Action Plan is developed to aid in initiating a timely and effective response to spills of oil and other hazardous materials originating from Ohio along the Ohio River (including its tributaries) between Ohio River mile markers 40.1 to 127.2. It is intended to be used during Operational Periods 1 and 2 of response only at the discretion of the Incident Commander. It is not intended to supercede th e dir ection of the Incident Commander or eliminate the need for ongoing communication during a response. IAP Approved by Incident Commander(s): ORG NAME DATE/TIME First Local IC (911, Fire Dept., County Emergency Mgr.) First Responding State (Ohio EPA, WVDEP) FOSC; USCG, EPA USFWS Lead Representative OH DNR/ WV DNR SE Ohio Sub-Area Spill Response Plan INITIAL INCIDENT ACTION PLAN EXECUTIVE SUMMARY In order to best prepare for oil and hazardous material spills originating from Ohio, along the Ohio River (including its tributaries) between Ohio River mile marker 40.1 to 127.2, an interagency team comprised of representatives from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA), U.S. Coast Guard (USCG), Ohio Environmental Protection Agency (Ohio EPA), the Ohio River Valley Water Sanitation Commission (ORSANCO) and other federal, state, local agencies, and private sector, identified the need for a specialized planning document that will: 1) describe the roles that agencies and other entities would likely play in an incident, and 2) give responders a mechanism to help organize both in advance and during a response. -

Ohio Archaeological Inventory Form Instruction Manual

Ohio Archaeological Inventory Form Instruction Manual With the support of the U.S. Department of the Interior’s Historic Preservation Fund and the Ohio Historic Preservation Office of the Ohio Historical Society Copyright © 2007 Ohio Historical Society, Inc. All rights reserved. The publication of these materials has been made possible in part by a grant from the U.S. Department of the Interior’s National Park Service, administered by the Ohio Historic Preservation Office. However, its contents do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the Department of the Interior, nor does the mention of trade names or commercial products imply their endorsement. The Ohio Historic Preservation Office receives federal assistance from the U.S. Department of the Interior’s Historic Preservation Fund. U.S. Department of the Interior regulations prohibit unlawful discrimination in depart- mental federally assisted programs on the basis of race, color, national origin, age or disability. Any person who believes he or she has been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility operated by a recipient of Federal assistance should write to: Office of Equal Opportunity, U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1849 C Street N.W., Washington D.C. 20240. Ohio Historic Preservation Office 567 East Hudson Street Columbus, Ohio 43211-1030 614/ 298-2000 Fax 614/ 298-2037 Visit us at www.ohiohistory.org OAl Rev. June 2003 Table of Contents Introduction and General Instructions 1 Definition of Archaeological Resource (Site) 1 Submitting an Ohio Archaeological Inventory Form 2 Itemized Instructions 3 A. Identification 3 1. Type of Form 3 2. -

2 0 2 0 2 1 Mediaguide

202021 MEDIA GUIDE Audrey TINGLE Jackie KITTS Olivia BELKNAP Coach COOPER 1 Section I #GoWLU INDEX SECTION I: WELCOME TO WEST LIBERTY WLU Quick Facts . 6 This is West Liberty! ...............7 Hilltoppersports.com . 8 Topper Station ...................8 Media Information . 9 Athletic Facilities . 10 Dr. W. Franklin Evans . 14 Athletic Director Lynn Ullom. 14 Support Staff ....................15 WLU Athletic Administration. 16 SECTION II: 2020-21 SEASON PREVIEW 2020-21 Season Preview ..........18 SECTION III: THE COACHES Head Coach Kyle Cooper. 23 Assistant Coaches. .24 SECTION IV: THE PLAYERS 2020-21 Rosters .................27 Returning Players. .28 New Faces ......................34 SECTION V: 2019-20 REVIEW Morgan Brunner – She’s No. 1!. 37 2019-20 Game-By-Game Scores. .38 2019-20 Season at a Glance .......39 2019-20 Season Stats, Highs/Lows 40 SECTION VI: HILLTOPPER HISTORY Annual Records, Coaches .........42 Hilltopper Honor Roll. 44 1,000-Point Scorers ..............45 NCAA Record Book. 46 NCAA Tournament History ........47 WELCOME TO All-Time Individual Records ........48 All-Time Series Records . 49 All-Time Game-by-Game Scores ....50 Hilltoppers at the ASRC ...........55 Single-Game Leaders . 56 Single-Season Leaders ............57 Career Leaders ..................58 WEST LIBER TY Conference History ..............59 2 2020-21 WEST LIBERTY UNIVERSITY WOMEN’S BASKETBALL MEDIA GUIDE 3 Section I #GoWLU COVID-19 ADVISORY Hey, TopperNation! West Liberty University is committed to enforcing all local, state and national guidelines to ensure the safety of everyone on the WLU campus during the current health crisis. Please do your part by wearing a mask and cooperating with all social distancing directives when attending a Hilltopper event. -

Beaver Creek State Forest and Surrounding Area

Beaver Creek State Forest and surrounding area 80°38'15"W 80°37'30"W 80°36'45"W 80°36'0"W 80°35'15"W 80°34'30"W 80°33'45"W 80°33'0"W 80°32'15"W 80°31'30"W 80°30'45"W East Carmel Union Ridge Achor 1:60,000 Legend Jackman Road 5 40°46'30"N Kilometers Beaver Creek State Forest 40°46'30"N 0 0.5 1 1.5 2 Beaver Creek State Park Miles Twp Hwy 2300 State Nature Preserve 0 0.5 Twp Hwy 10291 1.5 2 No Hunting Area Spruce Lake Roads State property boundaries shown are representative and believed to be correct but not warranted.Lake Tomahawk Twp Hwy 1030 State forest boundary lines on the ground are identified with signs and/or yellow paint marks on Abandoned railroads 40°45'45"N trees.Twp Hwy 905 This map may not include some local roadways. 40°45'45"N Streams Map reviewed and approved by Robert Boyles, Chief ODNR Division of Forestry, 1/2014 Designated Ohio Scenic River BEAVER CREEK Pancake Clarkson Road Data provided by ODNR Forestry, ODNR GIMS, US Census Tiger, ODOT Designated Ohio Wild River STATE FOREST Pancake Clarkson Road 40°45'0"N Clarkson Road Twp Hwy 904 Clarkson 40°45'0"N ^ Co Hwy 419 SHEEPSKIN HOLLOW NATURE PRESERVE Fredericktown Clarkson Road SR 7 SR SR 170 SR 40°44'15"N Twp Hwy 1034 Little Beaver Creek 40°44'15"N Middle Fork Carlisle Road Sprucevale Road Twp Hwy 959 Twp North Fork Williamsport Smith Road 40°43'30"N Little Beaver Creek 40°43'30"N Little Beaver Creek Echo Dell Road Twp Hwy 895 Fredericktown Fredericktown Road BEAVER CREEK STATE PARK 40°42'45"N Twp Hwy 912 40°42'45"N Bell School Road Sprucevale West Fork Little Beaver -

Mosquito Lake State Park Park State Lake Mosquito

printed on recycled content paper content recycled on printed An Equal Opportunity Employer - M/F/H - Employer Opportunity Equal An or by calling 866-OHIOPARKS. 866-OHIOPARKS. calling by or ohiostateparks.org Columbus, OH 43229 - 6693 - 43229 OH Columbus, 2045 Morse Rd. Morse 2045 Camping reservations may be made online at at online made be may reservations Camping Division of Parks & Watercraft & Parks of Division Ohio Department of Natural Resources Natural of Department Ohio campers. Pets are permitted on all sites. sites. all on permitted are Pets campers. a boat launching area with shoreline tie-ups for for tie-ups shoreline with area launching boat a basketball courts are available for use. There is is There use. for available are courts basketball campground. A playground and volleyball and and volleyball and playground A campground. toilets. Pit latrines are located throughout the the throughout located are latrines Pit toilets. Facilities include two showerhouses with flush flush with showerhouses two include Facilities large non-electric group camp areas. camp group non-electric large lakeshore access and vistas. There are also two two also are There vistas. and access lakeshore are situated in a mature forest, while others provide provide others while forest, mature a in situated are well as a new showerhouse. The majority of the sites sites the of majority The showerhouse. new a as well up sites were recently added to the campground, as as campground, the to added recently were sites up which offer 50/30/20 amp electric service. Full hook- Full service. electric amp 50/30/20 offer which 360-1552. -

RV Sites in the United States Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile

RV sites in the United States This GPS POI file is available here: https://poidirectory.com/poifiles/united_states/accommodation/RV_MH-US.html Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile Camp Map 370 Lakeside Park Map 5 Star RV Map 566 Piney Creek Horse Camp Map 7 Oaks RV Park Map 8th and Bridge RV Map A AAA RV Map A and A Mesa Verde RV Map A H Hogue Map A H Stephens Historic Park Map A J Jolly County Park Map A Mountain Top RV Map A-Bar-A RV/CG Map A. W. Jack Morgan County Par Map A.W. Marion State Park Map Abbeville RV Park Map Abbott Map Abbott Creek (Abbott Butte) Map Abilene State Park Map Abita Springs RV Resort (Oce Map Abram Rutt City Park Map Acadia National Parks Map Acadiana Park Map Ace RV Park Map Ackerman Map Ackley Creek Co Park Map Ackley Lake State Park Map Acorn East Map Acorn Valley Map Acorn West Map Ada Lake Map Adam County Fairgrounds Map Adams City CG Map Adams County Regional Park Map Adams Fork Map Page 1 Location Map Adams Grove Map Adelaide Map Adirondack Gateway Campgroun Map Admiralty RV and Resort Map Adolph Thomae Jr. County Par Map Adrian City CG Map Aerie Crag Map Aeroplane Mesa Map Afton Canyon Map Afton Landing Map Agate Beach Map Agnew Meadows Map Agricenter RV Park Map Agua Caliente County Park Map Agua Piedra Map Aguirre Spring Map Ahart Map Ahtanum State Forest Map Aiken State Park Map Aikens Creek West Map Ainsworth State Park Map Airplane Flat Map Airport Flat Map Airport Lake Park Map Airport Park Map Aitkin Co Campground Map Ajax Country Livin' I-49 RV Map Ajo Arena Map Ajo Community Golf Course Map -

A String That Goes Through My State

BUCKEYE TRAIL ASSOCIATION Trailblazer FOUNDED 1959 SUMMER 2015 VOLUME 48 NO. 2 A String That Goes Through My State Randall Roberts There is a theory today developed people are nothing alike and the by some physicists to explain the common purpose is inspired by very universe, energy, and the behavior different and individual motivations. of matter. It’s called string theory. I They varied in age, ability, stature, don’t pretend to understand all that, character, and personality. They but I do know that there’s a string that varied in education, occupation, goes around my state. If you look background, and experience. Some closely, and know where to look, on came because they want to preserve the state map prepared by the Ohio nature while others came just to Department of Transportation, you experience it. Some came to listen might find a dashed red line. It’s about adventures they only dream hard to follow, as it darts in and out of, or someday hope to experience of towns and on and off state and themselves firsthand. Some came county highways and other back roads to share their stories; because what identified on the map. It’s pretty easy good is an adventure if you can’t to miss, unless you know what you’re share it with others? The adventures looking for. The Legend Key simply themselves are as different as the identifies it as “Selected Hiking Trail”. individuals who came to present But many of us know exactly what it is them, be they circling the state on and where it is. -

Agenda Title Page

BEAVER LOCAL BOARD OF EDUCATION. BOARD MINUTES 2013 January 9, 2013 – Organizational/Regular Meeting The Beaver Local Board of Education met in regular session on Wednesday, January 9, 2013, at 6:30 P.M., in the Beaver Local High School Room 2. Action on agenda items for the regular section of the meeting was preceded by a work session open to the public. ATTENDANCE BOARD MEMBERS: OTHERS: Mr. Croxall Mr. Polen, Superintendent Mr. Eisenhart Mr. Barrett, Treasurer Mr. O’Hara Administrators and Supervisors Mr. Wolfe Other interested and concerned Mr. Campbell citizens and employees CALL TO ORDER The meeting was called to order by 2012 Board President, Mr. Campbell. The Pledge of Allegiance was recited in unison. The roll was called noting all members were present. ORGANIZATIONAL SECTION OF MEETING M-13.01 ELECTION OF BOARD PRESIDENT Mr. Croxall nominated Mr. Campbell to serve as President for 2013. Mr. Croxall moved, seconded by Mr. O’Hara, to close nominations. Roll Call: Mr. Croxall, yes; Mr. O’Hara, yes; Mr. Eisenhart, yes; Mr. Wolfe, yes; Mr. Campbell, yes. Motion approved. Mr. Campbell elected as President of the Board for 2013. M-13.02 ELECTION OF BOARD VICE-PRESIDENT Mr. Campbell nominated Mr. Eisenhart to serve as Vice-President for 2013. Mr. Croxall moved, seconded by Mr. O’Hara, to close nominations. Roll Call: Mr. Croxall, yes; Mr. O’Hara, yes; Mr. Eisenhart, abstain; Mr. Wolfe, yes; Mr. Campbell, yes. Motion approved by a vote of 4 to 0 to1. Mr. Eisenhart elected as Vice-President of the Board for 2013. M-13.03 DATE, PLACE, AND TIME OF REGULAR MEETINGS: Mr.