PERFORMING BIOGRAPHY: CREATING, EMBODYING and SHIFTING HISTORY PART I a Thesis Submitted by Bernadette Anne Meenach MA (QUT), Gr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Judy Garland (1922-1969)

1/22 Data Judy Garland (1922-1969) Pays : États-Unis Sexe : Féminin Naissance : Grand-Rapid (S. D.), 10-06-1922 Mort : Londres, 22-01-1969 Note : Chanteuse et actrice américaine Autre forme du nom : Frances Gumm (1922-1969) ISNI : ISNI 0000 0000 8380 6106 (Informations sur l'ISNI) Judy Garland (1922-1969) : œuvres (255 ressources dans data.bnf.fr) Œuvres audiovisuelles (y compris radio) (45) "Un enfant attend. - [2]" "Un enfant attend. - [2]" (2016) (2016) de Ernest Gold et autre(s) de Ernest Gold et autre(s) avec Judy Garland (1922-1969) comme Acteur avec Judy Garland (1922-1969) comme Acteur "Le magicien d'Oz" "Le magicien d'Oz" (2013) (2013) de Victor Fleming et autre(s) de Victor Fleming et autre(s) avec Judy Garland (1922-1969) comme Acteur avec Judy Garland (1922-1969) comme Acteur "La jolie fermière" "Till the clouds roll by" (2013) (2012) de George Wells et autre(s) de Richard Whorf et autre(s) avec Judy Garland (1922-1969) comme Acteur avec Judy Garland (1922-1969) comme Acteur "Le chant du Missouri" "Meet me in St. Louis. - Vincente Minnelli, réal.. - [2]" (2012) (2012) de Vincente Minnelli et autre(s) de Vincente Minnelli et autre(s) avec Judy Garland (1922-1969) comme Acteur avec Judy Garland (1922-1969) comme Acteur "Le chant du Missouri" "La pluie qui chante. - Richard Whorf, réal.. - [2]" (2011) (2010) de Vincente Minnelli et autre(s) de George Wells et autre(s) avec Judy Garland (1922-1969) comme Acteur avec Judy Garland (1922-1969) comme Acteur data.bnf.fr 2/22 Data "Le chant du Missouri" "Le magicien d'Oz" (2009) (2009) de Vincente Minnelli et autre(s) de Victor Fleming et autre(s) avec Judy Garland (1922-1969) comme Acteur avec Judy Garland (1922-1969) comme Acteur "The pirate" "La danseuse des Folies Ziegfeld" (2008) (2007) de Vincente Minnelli et autre(s) de Sonya Levien et autre(s) avec Judy Garland (1922-1969) comme Acteur avec Judy Garland (1922-1969) comme Acteur "Parade de printemps" "Un enfant attend. -

Issue 17 Ausact: the Australian Actor Training Conference 2019

www.fusion-journal.com Fusion Journal is an international, online scholarly journal for the communication, creative industries and media arts disciplines. Co-founded by the Faculty of Arts and Education, Charles Sturt University (Australia) and the College of Arts, University of Lincoln (United Kingdom), Fusion Journal publishes refereed articles, creative works and other practice-led forms of output. Issue 17 AusAct: The Australian Actor Training Conference 2019 Editors Robert Lewis (Charles Sturt University) Dominique Sweeney (Charles Sturt University) Soseh Yekanians (Charles Sturt University) Contents Editorial: AusAct 2019 – Being Relevant .......................................................................... 1 Robert Lewis, Dominique Sweeney and Soseh Yekanians Vulnerability in a crisis: Pedagogy, critical reflection and positionality in actor training ................................................................................................................ 6 Jessica Hartley Brisbane Junior Theatre’s Abridged Method Acting System ......................................... 20 Jack Bradford Haunted by irrelevance? ................................................................................................. 39 Kim Durban Encouraging actors to see themselves as agents of change: The role of dramaturgs, critics, commentators, academics and activists in actor training in Australia .............. 49 Bree Hadley and Kathryn Kelly ISSN 2201-7208 | Published under Creative Commons License (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0) From ‘methods’ to ‘approaches’: -

The Australian Theatre Family

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sydney eScholarship A Chance Gathering of Strays: the Australian theatre family C. Sobb Ah Kin MA (Research) University of Sydney 2010 Contents: Epigraph: 3 Prologue: 4 Introduction: 7 Revealing Family 7 Finding Ease 10 Being an Actor 10 Tribe 15 Defining Family 17 Accidental Culture 20 Chapter One: What makes Theatre Family? 22 Story One: Uncle Nick’s Vanya 24 Interview with actor Glenn Hazeldine 29 Interview with actor Vanessa Downing 31 Interview with actor Robert Alexander 33 Chapter Two: It’s Personal - Functioning Dysfunction 39 Story Two: “Happiness is having a large close-knit family. In another city!” 39 Interview with actor Kerry Walker 46 Interview with actor Christopher Stollery 49 Interview with actor Marco Chiappi 55 Chapter Three: Community −The Indigenous Family 61 Story Three: Who’s Your Auntie? 61 Interview with actor Noel Tovey 66 Interview with actor Kyas Sheriff 70 Interview with actor Ursula Yovich 73 Chapter Four: Director’s Perspectives 82 Interview with director Marion Potts 84 Interview with director Neil Armfield 86 Conclusion: A Temporary Unity 97 What Remains 97 Coming and Going 98 The Family Inheritance 100 Bibliography: 103 Special Thanks: 107 Appendix 1: Interview Information and Ethics Protocols: 108 Interview subjects and dates: 108 • Sample Participant Information Statement: 109 • Sample Participant Consent From: 111 • Sample Interview Questions 112 2 Epigraph: “Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way. Everything was in confusion in the Oblonsky’s house. The wife had discovered that the husband was carrying on an intrigue with a French girl, who had been a governess in their family, and she had announced to her husband that she could not go on living in the same house with him. -

Lightning Bolt

THE LIGHTNING BOLT CRAWFORD LEADS THE CHARGE MARIO GAME AND MOVIE REVIEWS COVID COVERAGE-THEATRE, SPORTS, TEACHERS,PROCEDURES VOLUME 33 iSSUE 1 CHANCELLOR HIGH SCHOOL 6300 HARRISON ROAD, FREDERICKSBURG, VA 22407 1 Sep/Oct 2020 RETIREMENT, RETURN TO SCHOOL, MRS. GATTIE AND CRAWFORD ADVISOR FAITH REMICK Left Mrs. Bass-Fortune is at her retirement parade on June EDITOR-IN-CHIEF 24 that was held to honor her many years at Chancellor High School. For more than three CARA SEELY hours decorated cars drove by the school, honking at Mrs. NEWS EDITOR Bass-Fortune, giving her gifts and well wishes. CARA HADDEN FEATURES EDITOR KAITLYN GARVEY SPORTS EDITOR STEPHANIE MARTINEZ & EMMA PURCELL OP-ED EDITORS Above and Left: Chancellor gets a facelift of decorated doors throughout the school. MIKAH NELSON Front Cover:New Principal Mrs. Cassandra Crawford & Back Cover: Newly Retired HAILEY PATTEN Mrs. Bass-Fortune CHARGING CORNER CHARGER FUR BABIES CONTEST MATCH THE NAME OF THE PET TO THE PICTURE AND TAKE YOUR ANSWERS TO ROOM A113 OR EMAIL LGATTIE@SPOT- SYLVANIA.K12.VA.US FOR A CHANCE TO WIN A PRIZE. HAVE A PHOTO OF YOUR FURRY FRIEND YOU WANT TO SUBMIT? EMAIL SUBMISSIONS TO [email protected]. Charger 1 Charger 2 Charger 3 Charger 4 Names to choose from. Note: There are more names than pictures! Banks, Sadie, Fenway, Bently, Spot, Bear, Prince, Thor, Sunshine, Lady Sep/Oct 2020 2 IS THERE REWARD TO THIS RISK? By Faith Remick school even for two days a many students with height- money to get our kids back Editor-In-Chief week is dangerous, and the ened behavioral needs that to school safely.” I agree. -

The Parkview Pantera

TThehe ParkviewParkview Pantera DECEMBER 2016 NEWS AROUND PHS Volume XLL, Edition I I Toys for Tots gives back to the community that the club accumulates in monetary donations is used to purchase additional toys, which are also sent to the warehouse for distribution. This year on all week- NEWS (2-3) ends through December 17th, JROTC students will be collecting donations in front of several, local Wal- Mart and Kroger stores, according to cadet private Annaliese Mayo, “Some- times, parents can’t afford to buy toys for their kids, and we’re trying to help those FEATURES (5-8) parents out so their kids can have toys too.” Parkview students can also contribute to the cause by donating to the Toys for Tots donation box in the front offi ce. Not everyone can enjoy the festivity of the holidays, Cadet Gunnery Sergeant Samantha Green (left) and Cadet Private Anna Mayo (right) do- and in recognition of such, nate their time to Toys for Tots during the holiday season. (Photo courtesy of Jolie Mayo) JROTC students are working OPINION (9-14) especially hard to ease the By Jenny Nguyen, Copy JROTC helps out in the op- donations through local strain for others who are less Editor erations of the U.S. Marine retail and grocery stores, has fortunate. “[The program] Corps Toys for Tots Pro- successfully expanded their impacts people, and I tell it The Christmas season gram, which serves to collect annual contributions to over to the students all the time. has offi cially come into its and deliver Christmas gifts $70,000. -

The Newark Public Schools Historical Preservation Committee MISSION

The Newark Public Schools Historical Preservation Committee MISSION The Newark Public Schools Historical Preservation Committee is a 501 (c)(3) organization formed in 2009 to chronicle the district’s rich heritage by preserving its documents, artifacts and school buildings. It is our intention to share the history of the Newark Public Schools with students and the greater com- munity at a permanent historic site. This Distinguished Alumni Directory is the first in a series of publications that we hope will help to inform and instill a sense of pride in our Newark history. 1 NEWARK PUBLIC SCHOOLS DISTINGUISHED ALUMNI The Newark Public School District Historical Preservation Committee GOALS ≈ To establish a policy and guidelines for the preservation and archiving of historically valuable artifacts of the Newark Public Schools. ≈ To establish repositories within the schools for the col- lection and preservation of valuable documents and materials relating to the history of the school district which otherwise would be lost. ≈ To develop and keep current a chronology of significant events in the Newark Public Schools. ≈ To identify and nominate public schools for listing on the National Register of Historic Places. ≈ To establish a permanent Newark Public Schools museum. ≈ To have students become involved with the archiving and chronicling process. To develop collaborative work- ing relationships with alumni associations and other preservation organizations. 2 NEWARK PUBLIC SCHOOLS DISTINGUISHED ALUMNI JANET LIPPMAN ABU-LUGHOD (Weequahic/1945) (1928–2013) Urban sociologist; expert on the history and dynamics of the World System and Middle Eastern cities; taught for twenty years at Northeastern; retired in 1988 as professor of sociology and historical research on the Gradu- ate Faculty of the New School for Social Research; her thirteen books include the classic work: Cairo: 100 Years of the City Victorious. -

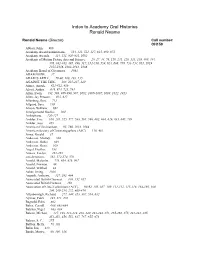

Index to Academy Oral Histories Ronald Neame

Index to Academy Oral Histories Ronald Neame Ronald Neame (Director) Call number: OH159 Abbott, John, 906 Academy Award nominations, 314, 321, 511, 517, 935, 969, 971 Academy Awards, 314, 511, 950-951, 1002 Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Science, 20, 27, 44, 76, 110, 241, 328, 333, 339, 400, 444, 476, 482-483, 495, 498, 517, 552-556, 559, 624, 686, 709, 733-734, 951, 1019, 1055-1056, 1083-1084, 1086 Academy Board of Governors, 1083 ADAM BEDE, 37 ADAM’S APPLE, 79-80, 100, 103, 135 AGAINST THE TIDE, 184, 225-227, 229 Aimee, Anouk, 611-612, 959 Alcott, Arthur, 648, 674, 725, 784 Allen, Irwin, 391, 508, 986-990, 997, 1002, 1006-1007, 1009, 1012, 1013 Allen, Jay Presson, 925, 927 Allenberg, Bert, 713 Allgood, Sara, 239 Alwyn, William, 692 Amalgamated Studios, 209 Ambiphone, 126-127 Ambler, Eric, 166, 201, 525, 577, 588, 595, 598, 602, 604, 626, 635, 645, 709 Ambler, Joss, 265 American Film Institute, 95, 766, 1019, 1084 American Society of Cinematogaphers (ASC), 118, 481 Ames, Gerald, 37 Anderson, Mickey, 366 Anderson, Robin, 893 Anderson, Rona, 929 Angel, Heather, 193 Ankers, Evelyn, 261-263 anti-Semitism, 562, 572-574, 576 Arnold, Malcolm, 773, 864, 876, 907 Arnold, Norman, 88 Arnold, Wilfred, 88 Asher, Irving, 1026 Asquith, Anthony, 127, 292, 404 Associated British Cinemas, 108, 152, 857 Associated British Pictures, 150 Association of Cine-Technicians (ACT), 90-92, 105, 107, 109, 111-112, 115-118, 164-166, 180, 200, 209-210, 272, 469-470 Attenborough, Richard, 277, 340, 353, 387, 554, 632 Aylmer, Felix, 185, 271, 278 Bagnold, Edin, 862 Baker, Carroll, 680, 883-884 Balchin, Nigel, 683, 684 Balcon, Michael, 127, 198, 212-214, 238, 240, 243-244, 251, 265-266, 275, 281-282, 285, 451-453, 456, 552, 637, 767, 855, 878 Balcon, S. -

Trade Moving to Same Col Tops Hot 100 Chart

OCTOBER 25, 1969 $1.00 SEVENTY-FIFTH YEAR The International Music -Record Tape Newsweekly COIN MACHINE Bi oa PAGES 41 TO 48 Trade Moving to Same Col Tops Hot 100 Chart 8 -Track, Cassette Price By BRUCE WEBUR Report; Keeps LP Lead LOS ANGELES - Industry The tape duplicator joins By FRED KIRBY trends point to a $6.98 stand- Columbia, RCA and Capitol, NEW YORK - Columbia Columbia also led for the Seven Arts complex, which also ard for both 8 -track and cas- among the major record manu- maintained its leading position third quarter on the Top LP's includes that label, which was by 1 sette, and Jan. an indus- facturers to establish a cassette in percentage of spots on Bill- Chart, but the top quarter Hot ninth with 23 titles for 3.6 per- try -wide price is ex- posture standard equal to that of its board's Top LP's Chart for the 100 scorer was RCA with 16 cent. Columbia's leading posi- pected. 8 -track cartridge product. first nine months of the year titles and 8.4 percent of the tion for last year's first three today's markups Many of in If traditional record labels, and gained the top position on chart, compared to Columbia's quarters was only supported by price tags as an come after- (Continued on page 14) Hot 100 percentage. 16 titles for 6.9 percent. 65 titles. math to rising costs at the man- ufacturing and distribution The nine -month Top's LP's RCA rose from its sixth spot leaders were points. -

Sugar Babies - the Quintessential Burlesque Show

SEPTEMBER,1986 Vol 10 No 8 ISSN 0314 - 0598 A publication of the Australian Elizabethan Theatre Trust Sugar Babies - The Quintessential Burlesque Show personality and his own jokes. Not all the companies, however, lived up to the audience's expectations; the comedians were not always brilliant and witty, the girls weren't always beautiful. This proved to be Ralph Allen's inspiration for SUGAR BABIES. "During the course of my research, one question kept recurring. Why not create a quintessen tial Burlesque Show out of authentic materials - a show of shows as I have played it so often in the theatre of my mind? After all, in a theatre of the mind, nothing ever disappoints. " After running for seven years in America - both in New York and on tour - the Australian Elizabethan Theatre Trust will mount SUGAR BABIES in Australia, opening in Sydney at Her Majesty's Theatre on October 30. In February it will move to Melbourne and other cities, including Adelaide, Perth and Auckland. The tour is expected to last about 39 weeks. Eddie Bracken, who is coming from the USA to star in the role of 1st comic in SUGAR BABIES, received rave reviews from critics in the USA. "Bracken, with his rolling eyes, rubber face and delightful slow burns, is the consummate performer, " said Jim Arpy in the Quad City Times. Since his debut in 1931 on Broadway, Bracken has appeared in Sugar Babies from the original New York production countless movies and stage shows. Garry McDonald will bring back to life one of Harry Rigby, happened to be at the con Australia's greatest comics by playing his SUGAR BABIES, conceived by role as "Mo" (Roy Rene). -

Staff Changes at Chancellor Spreading Cheer To

THE LIGHTNING BOLT Cheers!Salud SPREADING CHEER TO CHARITIES STAFF CHANGES AT CHANCELLOR MARIO GAME REVIEWS VOLUME 33 ISSUE 3 CHANCELLOR HIGH SCHOOL 6300 HARRISON ROAD, FREDERICKSBURG, VA 22407 1 December 2020 CHURCH QUILTERS SPREAD CHEER TO CHARITIES By Cara Hadden Features Editor With the holidays just around the corner, it is easy to get car- ried away with the shopping and coordinating gift lists and lose sight of the giving nature of the season. Nevertheless, as the old adage never fails to remind us, “It is better to give than to receive.” One group of women in particular have tak- en this to heart and make sure to carry the love of serving oth- ers with them year-round. The Piecemakers is a quilting ministry associated with Ref- ormation Lutheran Church in Culpeper, Virginia. The group has been together for eight years, and they make cotton quilts and fleece tie blankets to distribute to various charities during the Christmas season. The Piecemakers was found- ed by Dianne Vanderhoof, a quilting veteran with a gener- ous spirit and a member of Reformation Lutheran. “Ten years ago, I became partially The Piecemakers is a quilting group affiliated with Reformation Lutheran Church in Culpeper, Vir- disabled from a defective hip ginia. They meet every Saturday from 9:30 to 12:00 to sew cotton quilts and fleece tie quilts. replacement. There were a lot on quilts also helps me forget demic began, the women have hats, gloves, and scarves to be of things I could no longer do,” about the pain I’m in…[By do- been working on the blankets distributed between the five said Vanderhoof. -

Read PDF < Straight from the Horses Mouth: Ronald Neame

JCHB9GRXNYCN < eBook # Straight from the Horses Mouth: Ronald Neame, an Autobiography Straigh t from th e Horses Mouth : Ronald Neame, an A utobiograph y Filesize: 1.17 MB Reviews This is actually the finest pdf i have got study right up until now. It can be full of wisdom and knowledge Once you begin to read the book, it is extremely difficult to leave it before concluding. (Reese Morissette II) DISCLAIMER | DMCA R8BUZZDIPL8R // Doc Straight from the Horses Mouth: Ronald Neame, an Autobiography STRAIGHT FROM THE HORSES MOUTH: RONALD NEAME, AN AUTOBIOGRAPHY Scarecrow Press. Paperback. Book Condition: New. Paperback. 328 pages. Dimensions: 8.5in. x 5.5in. x 0.9in.Now in Paperback! Ronald Neames autobiography takes its title from one of his best-loved films, The Horses Mouth (1958), starring Alec Guinness. In an informative and entertaining style, Neame discusses the making of that film, along with several others, including In Which We Serve, Blithe Spirit, Brief Encounter, Great Expectations, Tunes of Glory, I Could Go on Singing, The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, Scrooge, The Poseidon Adventure, and Hopscotch. Straight from the Horses Mouth provides a fascinating, first-hand account of a unique filmmaker, who began his career as assistant cameraman on Hitchcocks first talkie, Blackmail, and went on to direct Maggie Smith, Judy Garland, Walter Matthau, and many other prominent performers. The book includes tales of the on-and-o-the-set antics of comedian George Formby, and original accounts of his experiences working with Noel Coward and David Lean. This is not simply an autobiography, but rather a history of British cinema from the 1920s through the 1960s, and Hollywood cinema from the 1960s through the present. -

CMS.701S15 Final Paper Student Examples

Current Debates In Digital Media Undergraduate Students Final Papers Edited by Gabrielle Trépanier-Jobin August, 2015 1 Table of Content Introduction Gabrielle Trépanier-Jobin CHAPTER 1 YouTube’s Participatory Culture: Online Communities, Social Engagement, and the Value of Curiosity By an MIT student. Used with permission. CHAPTER 2 Exploring Online Anonymity: Enabler of Harassment or Valuable Community-Building Tool? By an MIT student. Used with permission. CHAPTER 3 When EleGiggle Met E-sports: Why Twitch-Based E-Sports Has Changed By an MIT student. Used with permission. CHAPTER 4 Negotiating Ideologies in E-Sports By Ryan Alexander CHAPTER 5 The Moral Grey Area of Manga Scanlations By an MIT student. Used with permission. CHAPTER 6 The Importance of Distinguishing Act from Actor: A Look into the the Culture and Operations of Anonymous By Hannah Wood 2 INTRODUCTION By Gabrielle Trépanier-Jobin, PhD At the end of the course CMS 701 Current Debates in Media, students were asked to submit a 15 pages dissertation on the current debate of their choice. They had to discuss this debate by using the thesis/antithesis/synthesis method and by referring to class materials or other reliable sources. Each paper had to include a clear thesis statement, supporting evidence, original ideas, counter-arguments, and examples that illustrate their point of view. The quality and the diversity of the papers were very impressive. The passion of the students for their topic was palpable and their knowledge on social networks, e-sports, copyright infringment and hacktivism was remarkable. The texts published in this virtual booklet all received the highest grade and very good comments.