Gillingham, Erica

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LGBTQ America: a Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History Is a Publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service

Published online 2016 www.nps.gov/subjects/tellingallamericansstories/lgbtqthemestudy.htm LGBTQ America: A Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History is a publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service. We are very grateful for the generous support of the Gill Foundation, which has made this publication possible. The views and conclusions contained in the essays are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government. © 2016 National Park Foundation Washington, DC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted or reproduced without permission from the publishers. Links (URLs) to websites referenced in this document were accurate at the time of publication. THEMES The chapters in this section take themes as their starting points. They explore different aspects of LGBTQ history and heritage, tying them to specific places across the country. They include examinations of LGBTQ community, civil rights, the law, health, art and artists, commerce, the military, sports and leisure, and sex, love, and relationships. MAKING COMMUNITY: THE PLACES AND15 SPACES OF LGBTQ COLLECTIVE IDENTITY FORMATION Christina B. Hanhardt Introduction In the summer of 2012, posters reading "MORE GRINDR=FEWER GAY BARS” appeared taped to signposts in numerous gay neighborhoods in North America—from Greenwich Village in New York City to Davie Village in Vancouver, Canada.1 The signs expressed a brewing fear: that the popularity of online lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) social media—like Grindr, which connects gay men based on proximate location—would soon replace the bricks-and-mortar institutions that had long facilitated LGBTQ community building. -

Conflicts in Appraising Lesbian Pulp Novels Julie Botnick IS 438A

Pulp Frictions: Conflicts in Appraising Lesbian Pulp Novels Julie Botnick IS 438A: Seminar in Archival Appraisal June 14, 2018 Abstract The years between 1950 and 1965 were the “golden age” of lesbian pulp novels, which provided some of the only representations of lesbians in the mid-20th century. Thousands of these novels sit in plastic sleeves on shelves in special collections around the United States, val- ued for their evocative covers and campy marketing language. Devoid of accompanying docu- mentation which elaborates on the affective relationships lesbians had with these novels in their own time, the pulps are appraised for their value as visual objects rather than their role in peo- ple’s lives. The appraisal decisions made around these pulps are interdependent with irreversible decisions around access, exhibition, and preservation. I propose introducing affect as an appraisal criterion to build equitable collections which reflect full, holistic life experiences. This would do better justice to the women of the past who relied on these books for survival. !1 “Deep within me the joy spread… As my whole being convulsed in ecstasy I could feel Marilyn sharing my miracle.” From These Curious Pleasures by Sloan Britain, 1961 Lesbian pulp novels provided some of the only representations of lesbians in the mid-20th century. Cheaper than a pack of gum, these ephemeral novels were enjoyed in private and passed discreetly around, stuffed under mattresses, or tossed out with the trash. Today, thou- sands of these novels sit in plastic sleeves on shelves in special collections around the United States, valued for their evocative covers and campy marketing language. -

Duckie Archive

DUCKIE ARCHIVE (DUCKIE) ©Bishopsgate Institute Catalogued by Various, 2018-2019. DUCKIE Duckie Archive 1996-2018 Name of Creator: Duckie Extent: 55 Files Administrative/Biographical History: Amended from the Duckie Website (2020): Duckie are lowbrow live art hawkers, homo-social honky-tonkers and clubrunners for disadvantaged, but dynamically developing authentic British subcultures. Duckie create good nights out and culture clubs that bring communities together. From their legendary 24-year weekly residency at the Royal Vauxhall Tavern to winning Olivier awards at the Barbican, they are purveyors of progressive working class entertainment who mix live art and light entertainment. Duckie combine vintage queer clubbing, LGBTQI+ heritage & social archeology & quirky performance art shows with a trio of socially engaged culture clubs: The Posh Club (our swanky showbiz palais for working class older folk, now regular in five locations), The Slaughterhouse Club (our wellbeing project with homeless Londoners struggling with booze, addiction and mental health issues), Duckie QTIPOC Creatives (our black and brown LGBTQI youth theatre, currently on a pause until we bag a funder). Duckie have long-term relationships with a few major venues including Barbican Centre, Rich Mix, Southbank Centre and the Brighton Dome, but we mostly put on our funny theatre events in pubs, nightclubs, church halls and community centres. They are a National Portfolio Organisation of Arts Council England and revenue funded by the Big Lottery Fund. Duckie produce about 130 events and 130 workshops each year - mostly in London and the South East - and our annual audience is about 30,000 real life punters. Custodial History: Deposited with Bishopsgate Institute by Simon Casson, 2017. -

Back and Welcome to Unity's 2021 Programme of Events

2021 SEASON unitytheatreliverpool.co.uk Welcome back and welcome to Unity’s 2021 programme of events. We are delighted to finally be sharing Showcasing Local Talent with you some of the exciting productions With over 40 events and 100 artists and activities that form a special year already involved, our specially curated of work from Unity. reopening activities are a manifestation of this. Like everyone, our 2020 wasn’t quite the year we had planned. Originally Supporting Artists intended to be a landmark celebration This new season includes 22 of our 40th anniversary, instead we Merseyside-based creatives and found our doors closing indefinitely. companies who feature as part of The implications of the pandemic our Open Call Programme. Created and shutdown of venues across the UK to provide income and performance were serious and far-reaching, but they opportunity to local artists after allowed us to take stock and question a year without both, the Open Call our role as an arts organisation. celebrates these artists, their stories, communities and lives. What has emerged is a renewed commitment for Unity to provide 2021 welcomes a huge-new event space and opportunity for people series as part of our talent development to be creative, enjoy high-quality programme - Creative’pool. This will entertainment and celebrate the provide personalised training, workshops, communities of Liverpool. We want advice, exclusive events and development to continue to inspire creative opportunities to over 200 artists a year. risk and achieve a fairer, more supportive and accessible world. Access for All After a year of such uncertainty some of you may understandably be nervous about venturing into buildings. -

Bright Lights Film Festival Set to Screen Controversial Film 'Adam'

The Berkeley Beacon • November 11, 2019 • https://berkeleybeacon.com/bright-lights-film-festival-set- to-screen-controversial-film-adam/ Bright Lights Film Festival set to screen controversial film ‘Adam’ By Taina Millsap, Staff Writer Emerson College plans to screen Adam at the Nov. 12 Bright Lights Film Festival—a movie that has drawn significant criticism from the LGBTQ community and is the subject of a petition advocating for its removal from theaters. When the 2019 comedy film Adam premiered at Sundance Film Festival in January, it immediately drew negative attention from the LGBTQ community. Many queer people criticized the film for being homophobic and transphobic, with many calling for bans on the film with Anna Feder works as the curator of the Bright Lights Film petitions. Festival, which will bring controversial film 'Adam' to campus on Nov. 12. Montse Landeros / Beacon Staff One petition with over 4,100 signatures at the time of publication claims the film’s subject matter represents lesbian and transgender culture in a harmful way. “This movie is putting down trans men as not being real men. By implying that a lesbian would date a trans man,” the petition read. “Which isn’t true, because a lesbian only finds women sexually or romantically attractive. This movie puts down Lesbian and Trans culture. Which the LGBT+ community does not tolerate.” The movie currently has a 2.2/10 star rating on IMDb. The film is adapted from a book known by the same title, written by author Ariel Schrag. Wicked Queer, a Boston-based LGBTQ film festival, will co-present the film as part of Trans Awareness Week. -

Katy Shannahan Edited

1 Katy Shannahan OUHJ 2013 Submission The Impact of Failed Lesbian Feminist Ideology and Rhetoric Lesbian feminism was a radical feminist separatist movement that developed during the early 1970s with the advent of the second wave of feminism. The politics of this movement called for feminist women to extract themselves from the oppressive system of male supremacy by means of severing all personal and economic relationships with men. Unlike other feminist separatist movements, the politics of lesbian feminism are unique in that their arguments for separatism are linked fundamentally to lesbian identification. Lesbian feminist theory intended to represent the most radical form of the idea that the personal is political by conceptualizing lesbianism as a political choice open to all women.1 At the heart of this solution was a fundamental critique of the institution of heterosexuality as a mechanism for maintaining masculine power. In choosing lesbianism, lesbian feminists asserted that a woman was able to both extricate herself entirely from the system of male supremacy and to fundamentally challenge the patriarchal organization of society.2 In this way they privileged lesbianism as the ultimate expression of feminist political identity because it served as a means of avoiding any personal collaboration with men, who were analyzed as solely male oppressors within the lesbian feminist framework. Political lesbianism as an organized movement within the larger history of mainstream feminism was somewhat short lived, although within its limited lifetime it did produce a large body of impassioned rhetoric to achieve a significant theoretical 1 Radicalesbians, “The Woman-Identified Woman,” (1971). 2 Charlotte Bunch, “Lesbians In Revolt,” The Furies (1972): 8. -

Beyond Trashiness: the Sexual Language of 1970S Feminist Fiction

Journal of International Women's Studies Volume 4 Issue 2 Harvesting our Strengths: Third Wave Article 2 Feminism and Women’s Studies Apr-2003 Beyond Trashiness: The exS ual Language of 1970s Feminist Fiction Meryl Altman Follow this and additional works at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws Part of the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Altman, Meryl (2003). Beyond Trashiness: The exS ual Language of 1970s Feminist Fiction. Journal of International Women's Studies, 4(2), 7-19. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol4/iss2/2 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. This journal and its contents may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. ©2003 Journal of International Women’s Studies. Beyond Trashiness: The Sexual Language of 1970s Feminist Fiction By Meryl Altmani Abstract It is now commonplace to study the beginning of second wave US radical feminism as the history of a few important groups – mostly located in New York, Boston and Chicago – and the canon of a few influential polemical texts and anthologies. But how did feminism become a mass movement? To answer this question, we need to look also to popular mass-market forms that may have been less ideologically “pure” but that nonetheless carried the edge of feminist revolutionary thought into millions of homes. This article examines novels by Alix Kates Shulman, Marge Piercy and Erica Jong, all published in the early 1970s. -

Patricia Highsmith's Queer Disruption: Subverting Gay Tragedy in the 1950S

Patricia Highsmith’s Queer Disruption: Subverting Gay Tragedy in the 1950s By Charlotte Findlay A thesis submitted to Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English Literature Victoria University of Wellington 2019 ii iii Contents Acknowledgements ………………………………………………………………..……………..iv Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………………v Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………..1 1: Rejoicing in Evil: Queer Ambiguity and Amorality in The Talented Mr Ripley …………..…14 2: “Don’t Do That in Public”: Finding Space for Lesbians in The Price of Salt…………………44 Conclusion ...…………………………………………………………………………………….80 Works Cited …………..…………………………………………………………………………83 iv Acknowledgements Thanks to my supervisor, Jane Stafford, for providing always excellent advice, for helping me clarify my ideas by pointing out which bits of my drafts were in fact good, and for making the whole process surprisingly painless. Thanks to Mum and Tony, for keeping me functional for the last few months (I am sure all the salad improved my writing immensely.) And last but not least, thanks to the ladies of 804 for the support, gossip, pad thai, and niche literary humour I doubt anybody else would appreciate. I hope your year has been as good as mine. v Abstract Published in a time when tragedy was pervasive in gay literature, Patricia Highsmith’s 1952 novel The Price of Salt, published later as Carol, was the first lesbian novel with a happy ending. It was unusual for depicting lesbians as sympathetic, ordinary women, whose sexuality did not consign them to a life of misery. The novel criticises how 1950s American society worked to suppress lesbianism and women’s agency. It also refuses to let that suppression succeed by giving its lesbian couple a future together. -

MUSIC LIST Email: Info@Partytimetow Nsville.Com.Au

Party Time Page: 1 of 73 Issue: 1 Date: Dec 2019 JUKEBOX Phone: 07 4728 5500 COMPLETE MUSIC LIST Email: info@partytimetow nsville.com.au 1 THING by Amerie {Karaoke} 100 PERCENT PURE LOVE by Crystal Waters 1000 STARS by Natalie Bassingthwaighte {Karaoke} 11 MINUTES by Yungblud - Halsey 1979 by Good Charlotte {Karaoke} 1999 by Prince {Karaoke} 19TH NERVIOUS BREAKDOWN by The Rolling Stones 2 4 6 8 MOTORWAY by The Tom Robinson Band 2 TIMES by Ann Lee 20 GOOD REASONS by Thirsty Merc {Karaoke} 21 - GUNS by Greenday {Karaoke} 21 QUESTIONS by 50 Cent 22 by Lilly Allen {Karaoke} 24K MAGIC by Bruno Mars 3 by Britney Spears {Karaoke} 3 WORDS by Cheryl Cole {Karaoke} 3AM by Matchbox 20 {Karaoke} 4 EVER by The Veronicas {Karaoke} 4 IN THE MORNING by Gwen Stefani {Karaoke} 4 MINUTES by Madonna And Justin 40 MILES OF ROAD by Duane Eddy 409 by The Beach Boys 48 CRASH by Suzi Quatro 5 6 7 8 by Steps {Karaoke} 500 MILES by The Proclaimers {Karaoke} 60 MILES AN HOURS by New Order 65 ROSES by Wolverines 7 DAYS by Craig David {Karaoke} 7 MINUTES by Dean Lewis {Karaoke} 7 RINGS by Ariana Grande {Karaoke} 7 THINGS by Miley Cyrus {Karaoke} 7 YEARS by Lukas Graham {Karaoke} 8 MILE by Eminem 867-5309 JENNY by Tommy Tutone {Karaoke} 99 LUFTBALLOONS by Nena 9PM ( TILL I COME ) by A T B A B C by Jackson 5 A B C BOOGIE by Bill Haley And The Comets A BEAT FOR YOU by Pseudo Echo A BETTER WOMAN by Beccy Cole A BIG HUNK O'LOVE by Elvis A BUSHMAN CAN'T SURVIVE by Tania Kernaghan A DAY IN THE LIFE by The Beatles A FOOL SUCH AS I by Elvis A GOOD MAN by Emerson Drive A HANDFUL -

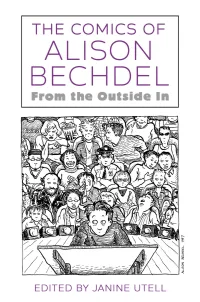

The Comics of Alison Bechdel from the Outside In

The Comics of Alison Bechdel From the Outside In Edited by Janine Utell University Press of Mississippi / Jackson CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS IX THE WORKS OF ALISON BECHDEL XI INTRODUCTION Serializing the Self in the Space between Life and Art JANINE UTELL XIII I. IN AND/OR OUT: QUEER THEORY, LESBIAN COMICS, AND THE MAINSTREAM THE HOSPITABLE AESTHETICS OF ALISON BECHDEL VANESSA LAUBER 3 “GIRLIE MAN, MANLY GIRL, IT’S ALL THE SAME TO ME” How Dykes to Watch Out For Shifted Gender and Comix ANNE N. THALHEIMER 22 DISSEMINATING QUEER THEORY Dykes to Watch Out For and the Transmission of Theoretical Thought KATHERINE PARKER-HAY 36 BECHDEL’S MEN AND MASCULINITY Gay Pedant and Lesbian Man JUDITH KEGAN GARDINER 52 VI CONTENTS MO VAN PELT Dykes to Watch Out For and Peanuts MICHELLE ANN ABATE 68 II. INTERIORS: FAMILY, SUBJECTIVITY, MEMORY DANCING WITH MEMORY IN FUN HOME ALISSA S. BOURBONNAIS 89 “IT BOTH IS AND ISN’T MY LIFE” Autobiography, Adaptation, and Emotion in Fun Home, the Musical LEAH ANDERST 105 GENERATIONAL TRAUMA AND THE CRISIS OF APRÈS-COUP IN ALISON BECHDEL’S GRAPHIC MEMOIRS NATALJA CHESTOPALOVA 119 THE EXPERIMENTAL INTERIORS OF ALISON BECHDEL’S ARE YOU MY MOTHER? YETTA HOWARD 135 INCHOATE KINSHIP Psychoanalytic Narrative and Queer Relationality in Are You My Mother? TYLER BRADWAY 148 III. PLACE, SPACE, AND COMMUNITY DECOLONIZING RURAL SPACE IN ALISON BECHDEL’S FUN HOME KATIE HOGAN 167 FUN HOME AND ARE YOU MY MOTHER? AS AUTOTOPOGRAPHY Queer Orientations and the Politics of Location KATHERINE KELP-STEBBINS 181 CONTENTS VII INSIDE THE ARCHIVES OF FUN HOME SUSAN R. -

National Conference

NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF THE POPULAR CULTURE ASSOCIATION AMERICAN CULTURE ASSOCIATION In Memoriam We honor those members who passed away this last year: Mortimer W. Gamble V Mary Elizabeth “Mery-et” Lescher Martin J. Manning Douglas A. Noverr NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF THE POPULAR CULTURE ASSOCIATION AMERICAN CULTURE ASSOCIATION APRIL 15–18, 2020 Philadelphia Marriott Downtown Philadelphia, PA Lynn Bartholome Executive Director Gloria Pizaña Executive Assistant Robin Hershkowitz Graduate Assistant Bowling Green State University Sandhiya John Editor, Wiley © 2020 Popular Culture Association Additional information about the PCA available at pcaaca.org. Table of Contents President’s Welcome ........................................................................................ 8 Registration and Check-In ............................................................................11 Exhibitors ..........................................................................................................12 Special Meetings and Events .........................................................................13 Area Chairs ......................................................................................................23 Leadership.........................................................................................................36 PCA Endowment ............................................................................................39 Bartholome Award Honoree: Gary Hoppenstand...................................42 Ray and Pat Browne Award -

Ann Bannon B

ANN BANNON b. September 15, 1932 AUTHOR “We wrote the stories no one else could tell.” “We were exploring a Ann Bannon is an author best known for her lesbian-themed fiction series, “The corner of the human spirit Beebo Brinker Chronicles.” The popularity of the novels earned her the title “The that few others were Queen of Lesbian Pulp Fiction.” writing about.” In 1954, Bannon graduated from the University of Illinois with a degree in French. During her college years she was influenced by the lesbian novels “The Well of Loneliness,” by Radclyffe Hall, and “Spring Fire,” by Vin Packer. At 24, Bannon published her first novel, “Odd Girl Out.” Born Ann Weldy, she adopted the pen name Ann Bannon because she did not want to be associated with lesbian pulps. Although she was married to a man, she secretly spent weekends in Greenwich Village exploring the lesbian nightlife. Between 1957 and 1962, she wrote “I Am A Woman,” “Women in the Shadows,” “Journey to a Woman” and “Beebo Brinker.” Together they constitute the “The Beebo Brinker Chronicles.” The series centers on young lesbians living in Greenwich Village and is noted for its accurate and sympathetic portrayal of gay and lesbian life. “We were exploring a corner of the human spirit that few others were writing about, or ever had,” said Bannon, “And we were doing it in a time and place where our needs and hopes were frankly illegal.” In 1980, when her books were reprinted, she claimed authorship of the novels. In 2004, “The Beebo Brinker Chronicles” was adapted into a successful stage play.