Demoralization-Led Migration in Bangladesh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

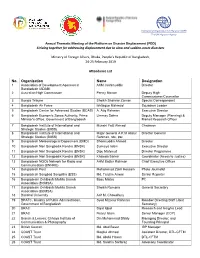

Annual Thematic Meeting of the Platform on Disaster Displacement (PDD) Striving Together for Addressing Displacement Due to Slow and Sudden-Onset Disasters

Annual Thematic Meeting of the Platform on Disaster Displacement (PDD) Striving together for addressing displacement due to slow and sudden-onset disasters Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Dhaka, People’s Republic of Bangladesh, 24-25 February 2019 Attendance List No. Organization Name Designation 1 Association of Development Agencies in AKM Jashimuddin Director Bangladesh (ADAB) 2 Australian High Commission Penny Morton Deputy High Commissioner/Counsellor 3 Bangla Tribune Sheikh Shahriar Zaman Special Correspondent 4 Bangladesh Air Force Ishtiaque Mahmud Squadron Leader 5 Bangladesh Centre for Advanced Studies (BCAS) A. Atiq Rahman Executive Director 6 Bangladesh Economic Zones Authority, Prime Ummay Salma Deputy Manager (Planning) & Minister's Office, Government of Bangladesh Market Research Officer 7 Bangladesh Institute of International and Munshi Faiz Ahmad Chairman Strategic Studies (BIISS) 8 Bangladesh Institute of International and Major General A K M Abdur Director General Strategic Studies (BIISS) Rahman, ndc, psc 9 Bangladesh Meteorological Department (BMD) Shamsuddin Ahmed Director 10 Bangladesh Nari Sangbadik Kendra (BNSK) Sumaiya Islam Executive Director 11 Bangladesh Nari Sangbadik Kendra (BNSK) Dipu Mahmud Director Programme 12 Bangladesh Nari Sangbadik Kendra (BNSK) Khaleda Sarkar Coordinator (Acess to Justice) 13 Bangladesh NGOs Network for Radio and AHM Bazlur Rahman Chief Executive Officer Communication (BNNRC) 14 Bangladesh Post Mohammad Zakir Hossain Photo Journalist 15 Bangladesh Sangbad Sangstha (BSS) Md. Tanzim Anwar -

City, Culture and Consumption: a Study on Youth in Dhaka City from 1990 – 2015

City, Culture and Consumption: A Study on Youth in Dhaka City from 1990 – 2015 A dissertation submitted to the University of Dhaka for the Degree of Masters in Philosophy in Sociology Submitted By Aklima Zaman Department of Sociology University of Dhaka Dhaka – 1205, Bangladesh. i Declaration by the Researcher I hereby declare that the M.Phil dissertation entitled “City, Culture and Consumption: A Study on Youth in Dhaka City from 1990 – 2015” has been prepared by me. It is an original work that has been done by me through taking advices and suggestions from my supervisor. This dissertation or any part of it has not been submitted to any academic institution or organization for any degree or Diploma or publication before. Aklima Zaman. Research Fellow Registration No. 296 / 2012 – 2013 Department of Sociology University of Dhaka Dhaka – 1205, Bangladesh. ii Certificate of Supervisor This is to certify that Aklima Zaman bearing Registration No.296 / 2012- 2013 has prepared the M.Phil the dissertation entitled “City, Culture and Consumption : A Study on Youth in Dhaka City from 1990 – 2015” under my direct guidance and supervision. This is her original work as well as this dissertation or any part of it has not been submitted to any academic institution or organization for any degree or Diploma or publication before. Professor Salma Akhter. Department of Sociology. University of Dhaka Dhaka – 1205, Bangladesh. iii Abstract Fundamental changes in various aspects of the world have been noticed in the last two decades, where technology and the mass media play an important role in the appearance of such changes. -

The Pennsylvania State University the Graduate School

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Agricultural Sciences POVERTY DYNAMICS AND HOUSEHOLD RESPONSE: DISASTER SHOCKS IN RURAL BANGLADESH A Thesis in Agricultural, Environmental and Regional Economics and Demography by Anuja Jayaraman © 2006 Anuja Jayaraman Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2006 The thesis of Anuja Jayaraman was received and approved* by the following Jill. L. Findeis Professor of Agricultural, Environmental and Regional Economics and Demography Thesis Advisor Chair of Committee Carolyn E. Sachs Professor of Rural Sociology and Women’s Studies Gretchen T. Cornwell Research Associate and Assistant Professor of Rural Sociology and Demography Bee-Yan Roberts Professor of Economics Stephen M. Smith Professor of Agricultural and Regional Economics Committee Member and Head of Department of Agricultural Economics and Rural Sociology * Signatures are on file in the Graduate School. Abstract South Asia has the largest concentration of the world’s poor, with over half a billion people surviving on less than a dollar a day. One of the Millennium Development Goals (MDG) aims to halve the proportion of the world’s people whose income is less than one dollar a day and the proportion of people who suffer from hunger by the year 2015. The success of poverty alleviation programs in South Asia is critical if this MDG is to be met. Within South Asia, Bangladesh has the highest incidence of poverty and only India and China have larger numbers of poor people. It is estimated that nearly half of Bangladesh’s population of 135 million people live below the poverty line. -

ASTI Country Brief Bangladesh

facilitated by APAARI ASTI Country Brief | July 2019 and IFPRI INDO-PACIFIC BANGLADESH Gert-Jan Stads, Md. Mustafizur Rahman, Alejandro Nin-Pratt, and Lang Gao AGRICULTURAL RESEARCH SPENDING BANGLADESH INDIA (2014) NEPAL SRI LANKA 7,500 Million taka 6,000 (2011 constant prices) 6,664.0 4,500 3,000 Million PPP dollars 1,500 (2011 constant prices) 287.9 3,298.4 81.9 112.4 0 2000 2002 2004 2006 2008 2010 2012 2014 2016 SPENDING INTENSITY 1.00 0.90 0.80 0.70 Agricultural research 0.60 0.50 spending as a share 0.40 of AgGDP 0.38% 0.30% 0.42% 0.62% 0.30 0.20 0.10 0.00 2000 2002 2004 2006 2008 2010 2012 2014 2016 AGRICULTURAL RESEARCHERS 2,500 Full-time 2,000 equivalents 2,268.6 12,746.6 519.7 648.0 1,500 1,000 Share of researchers with 500 MSc and PhD degrees 91% 99% 71% 78% 0 2000 2002 2004 2006 2008 2010 2012 2014 2016 Notes: Data in the table above are for 2016. Information on access to further resources, data procedures and methodologies, and acronyms and definitions are provided on Page 8. See www.asti. cgiar.org/bangladesh/directory for an overview of Bangladesh’s agricultural R&D agencies. Agricultural research investment Despite this growth, Bangladesh Although research staff numbers and and human resource capacity still only invested 0.38 percent of its qualification levels have gradually improved in Bangladesh have grown AgGDP in agricultural research in over time, an aging pool of PhD-qualified considerably in recent years, 2016—well below the level needed to researchers remains as an important largely as a result of increased address multiple challenges, including challenge. -

Factors Affecting Drinking Water Security in South-Western Bangladesh

Factors Affecting Drinking Water Security in South-Western Bangladesh By Laura Mahoney Benneyworth, M.S., GISP Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Interdisciplinary Studies: Environmental Management August, 2016 Nashville, Tennessee Approved Jonathan Gilligan, PhD Steven Goodbred, PhD John Ayers, PhD James H. Clarke, PhD Copyright © 2016 by Laura Mahoney Benneyworth ii for the children of Bangladesh, with hope for a brighter future iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the Vanderbilt Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering's Center for Environmental Management Studies (VCEMS) program and Vanderbilt's Earth and Environmental Sciences Department for their willingness to work together on my behalf to make this interdisciplinary project possible, and for their educational and financial support. I consider myself fortunate to have been involved in such an interesting and meaningful project. I am grateful for the guidance of my advisor, Jonathan Gilligan, and for his patience, kindness and encouragement. I am also appreciative of Jim Clarke, who provided me with this degree opportunity, for 30 years of good advice, and for always being my advocate. Steve Goodbred, John Ayers and Carol Wilson were continually helpful and supportive, and always a pleasure to work with. I am also thankful for the moral support of my friends and family, and for the friendship of other graduate students who made my journey a memorable one, including Bethany, Sandy, Lindsay, Leslie W., Chris T., Greg, Leslie D., Michelle, Laura P., Lyndsey, and Jenny. I would also like to extend my sincere gratitude to our Bangladeshi colleagues, for their technical assistance and their friendship, which made this work possible. -

The State, Democracy and Social Movements

The Dynamics of Conflict and Peace in Contemporary South Asia This book engages with the concept, true value, and function of democracy in South Asia against the background of real social conditions for the promotion of peaceful development in the region. In the book, the issue of peaceful social development is defined as the con- ditions under which the maintenance of social order and social development is achieved – not by violent compulsion but through the negotiation of intentions or interests among members of society. The book assesses the issue of peaceful social development and demonstrates that the maintenance of such conditions for long periods is a necessary requirement for the political, economic, and cultural development of a society and state. Chapters argue that, through the post-colo- nial historical trajectory of South Asia, it has become commonly understood that democracy is the better, if not the best, political system and value for that purpose. Additionally, the book claims that, while democratization and the deepening of democracy have been broadly discussed in the region, the peace that democracy is supposed to promote has been in serious danger, especially in the 21st century. A timely survey and re-evaluation of democracy and peaceful development in South Asia, this book will be of interest to academics in the field of South Asian Studies, Peace and Conflict Studies and Asian Politics and Security. Minoru Mio is a professor and the director of the Department of Globalization and Humanities at the National Museum of Ethnology, Japan. He is one of the series editors of the Routledge New Horizons in South Asian Studies and has co-edited Cities in South Asia (with Crispin Bates, 2015), Human and International Security in India (with Crispin Bates and Akio Tanabe, 2015) and Rethinking Social Exclusion in India (with Abhijit Dasgupta, 2017), also pub- lished by Routledge. -

English Language Newspaper Readability in Bangladesh

Advances in Journalism and Communication, 2016, 4, 127-148 http://www.scirp.org/journal/ajc ISSN Online: 2328-4935 ISSN Print: 2328-4927 Small Circulation, Big Impact: English Language Newspaper Readability in Bangladesh Jude William Genilo1*, Md. Asiuzzaman1, Md. Mahbubul Haque Osmani2 1Department of Media Studies and Journalism, University of Liberal Arts Bangladesh, Dhaka, Bangladesh 2News and Current Affairs, NRB TV, Toronto, Canada How to cite this paper: Genilo, J. W., Abstract Asiuzzaman, Md., & Osmani, Md. M. H. (2016). Small Circulation, Big Impact: Eng- Academic studies on newspapers in Bangladesh revolve round mainly four research lish Language Newspaper Readability in Ban- streams: importance of freedom of press in dynamics of democracy; political econo- gladesh. Advances in Journalism and Com- my of the newspaper industry; newspaper credibility and ethics; and how newspapers munication, 4, 127-148. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ajc.2016.44012 can contribute to development and social change. This paper looks into what can be called as the fifth stream—the readability of newspapers. The main objective is to Received: August 31, 2016 know the content and proportion of news and information appearing in English Accepted: December 27, 2016 Published: December 30, 2016 language newspapers in Bangladesh in terms of story theme, geographic focus, treat- ment, origin, visual presentation, diversity of sources/photos, newspaper structure, Copyright © 2016 by authors and content promotion and listings. Five English-language newspapers were selected as Scientific Research Publishing Inc. per their officially published circulation figure for this research. These were the Daily This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International Star, Daily Sun, Dhaka Tribune, Independent and New Age. -

NO PLACE for CRITICISM Bangladesh Crackdown on Social Media Commentary WATCH

HUMAN RIGHTS NO PLACE FOR CRITICISM Bangladesh Crackdown on Social Media Commentary WATCH No Place for Criticism Bangladesh Crackdown on Social Media Commentary Copyright © 2018 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-36017 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org MAY 2018 ISBN: 978-1-6231-36017 No Place for Criticism Bangladesh Crackdown on Social Media Commentary Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Information and Communication Act ......................................................................................... 3 Punishing Government Critics ...................................................................................................4 Protecting Religious -

Freemuse-Drik-PEN-International

Joint submission to the mid-term Universal Periodic Review of Bangladesh by Freemuse, Drik, and PEN International 4 December 2020 Executive summary Freemuse, Drik, and PEN International welcome the opportunity to contribute to the mid-term review of the Universal Periodic Review (UPR) on Bangladesh. This submission evaluates the implementation of recommendations made in the previous UPR and assesses the Bangladeshi authorities’ compliance with international human rights obligations with respect to freedoms of expression, information and peaceful assembly, in particular concerns related to: - Digital Security Act and Information and Communication Technology Act - Limitations on freedom of religion and belief - Restrictions to the right to peaceful assembly and political engagement - Attacks on artistic freedom and academic freedom As part of the third cycle UPR process in 2018, the Government of Bangladesh accepted 178 recommendations and noted 73 out of a total 251 recommendations received. This included some aimed at guaranteeing the rights to freedom of expression, information and peaceful assembly. However, a crackdown on freedom of expression has been intensified since the review and civil society, including artists and journalists, has faced adversity from authorities. These are in violation of Bangladesh’s national and international commitments to artistic freedom, specifically the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights which were ratified by the authorities in 2000 and 1998, respectively. This UPR mid-term review was compiled based on information from Freemuse, Drik and PEN International. 1 SECTION A Digital Security Act: a threat to freedom of expression Third Cycle UPR Recommendations The Government of Bangladesh accepted recommendations 147.67, 147.69, 147.70, 148.3, 148.13, 148.14, and 148.15 concerning the Information and Communication Technology Act and Digital Security Act. -

Concert for Migrants’ at a Glance: to Celebrate International Migrants Day 2020, a Virtual Concert Titled ‘Concert for Migrants’ Was Organized on 18 December 2020

‘Concert for Migrants’ at A Glance: To celebrate International Migrants Day 2020, a virtual concert titled ‘Concert for Migrants’ was organized on 18 December 2020. Featuring popular singers from home and abroad, the concert has reached more than 3.3 million people in more than 30 countries worldwide. In between performing a range of popular songs, the celebrities spoke on the importance of informed migration decisions contributing to regular, safe, and orderly migration, sustainable reintegration as well as migration governance. Outreach of the Concert Number of people reached online 1.9 Million Number of people watched the concert on TV 1.4 Million Total 3.3 Million Name of the top 15 countries from where Bangladesh, Oman, Saudi Arabia, Libya, Qatar, Lebanon, Kuwait, people watched the concert Bahrain, Jordan, Malaysia, Singapore, UK, Egypt, Italy, and Japan Number of media report produced 37+ A number of creative content were developed and shared on our social media platforms with the endorsement of celebrities. Video messages of the singers: • Fahmida Nabi: https://fb.watch/2Nh7wL_j-c/ • Sania Sultana Liza: https://fb.watch/2Nh5OeaFrB/ • S.I. Tutul: https://fb.watch/2Nh6HEtrjW/ • Sahos Mostafiz: https://fb.watch/2NhdDW4VBj/ • Fakir Shabuddin: https://fb.watch/2NhavHLAXI/ • Xefer Rahman: https://fb.watch/2NhfsHFkb2/ • Polash Noor: https://fb.watch/2Nh3fURc-Z/ • Nowshad Ferdous: https://fb.watch/2NhgfU2SfA/ • Mizan Mahmud Razib: https://fb.watch/2Nh9_iwehf/ Promo: https://fb.watch/2NhcsD5lRB/ Media Reports on the Concert: 1. Daily Star 11. Daily Asian Age 21. Dainik Amader Shomoy 31. Barta 24 2. Dhaka Tribune 12. Daily Ittefaq 22. Newshunt 32. Change 24 3. -

Traditional Institutions As Tools of Political Islam in Bangladesh

01_riaz_055072 (jk-t) 15/6/05 11:43 am Page 171 Traditional Institutions as Tools of Political Islam in Bangladesh Ali Riaz Illinois State University, USA ABSTRACT Since 1991, salish (village arbitration) and fatwa (religious edict) have become common features of Bangladesh society, especially in rural areas. Women and non-governmental development organizations (NGOs) have been subjected to fatwas delivered through a traditional social institution called salish. This article examines this phenomenon and its relationship to the rise of Islam as political ideology and increasing strengths of Islamist parties in Bangladesh. This article challenges existing interpretations that persecution of women through salish and fatwa is a reaction of the rural community against the modernization process; that fatwas represent an important tool in the backlash of traditional elites against the impoverished rural women; and that the actions of the rural mullahs do not have any political links. The article shows, with several case studies, that use of salish and fatwa as tools of subjection of women and development organizations reflect an effort to utilize traditional local institutions to further particular interpretations of behavior and of the rights of indi- viduals under Islam, and that this interpretation is intrinsically linked to the Islamists’ agenda. Keywords: Bangladesh; fatwa; political Islam Introduction Although the alarming rise of the militant Islamists in Bangladesh and their menacing acts in the rural areas have received international media attention in recent days (e.g. Griswold, 2005), the process began more than a decade ago. The policies of the authoritarian military regimes that ruled Bangladesh between 1975 and 1990, and the politics of expediency of the two major politi- cal parties – the Awami League (AL) and the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) – enabled the Islamists to emerge from the political wilderness to a legit- imate political force in the national arena (Riaz, 2003). -

Media Coverage Links

Pneumonia in Bangladesh: Where we are and what need to do Media Coverage Links 1. icddr,b press release - https://www.icddrb.org/quick-links/press-releases?id=98&task=view 2. UNB (news agency) - http://www.unb.com.bd/category/Bangladesh/pneumonia-kills-24000- plus-children-in-bangladesh-every-year/60359 3. The Daily Star - https://www.thedailystar.net/city/news/juvenile-pneumonia-ignored-due- covid-pandemic-experts-1993417 4. Dhaka Tribune (English) https://www.dhakatribune.com/bangladesh/2020/11/11/every-hour- pneumonia-kills-3-children-in-bangladesh 5. Dhaka Tribune (Bangla) https://bit.ly/3ngKe2H 6. The New Age - https://www.newagebd.net/article/121327/67-children-die-of-pneumonia- daily:-study 7. The Observer BD - https://www.observerbd.com/news.php?id=284093 8. The Business Standard - https://tbsnews.net/bangladesh/health/67-children-die-pneumonia- every-day-bangladesh-156727 9. The Financial Express - https://www.thefinancialexpress.com.bd/health/pneumonia-kills-67- children-every-day-in-bangladesh-1605157926 10. The Independent - http://www.theindependentbd.com/post/255893 11. Bangladesh Post (print and online – English) - https://www.bangladeshpost.net/posts/pneumonia-still-number-one-killer-of-bangladeshi- children-46768 12. The Daily Sun (print and online – English) - https://www.daily- sun.com/post/517196/Preventing-child-death-from-pneumonia-requires-multi-system-approach 13. The New Nation (print and online – English) - http://thedailynewnation.com/news/268690/67-children-die-of-pneumonia-every-day-in- bangladesh.html 14. The Bangladesh and Beyond (online – English) - https://thebangladeshbeyond.com/preventing- child-death-from-pneumonia-requires-multi-system-approach-health-experts/ 15.