2021.08.17 SW FTC Submission

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catalyzing CTE Grant 2017

rationale Rockingham County is faced with daunting economic challenges. The exo- dus of its textile manufacturing base has not only left the county in search of new employment opportunities but has also left the county in search of a new identity. The types of relatively low skilled work that afforded our students’ parents and grandparents with a family-sustaining wage have all but disappeared. Hence, there exists much uncertainty as to what will emerge as the new economic driver within the county. We believe that Rock- ingham County Schools, in collaboration Spray Cotton Mill Eden, NC with Rockingham Community College (RCC) along with business and community leaders, have to play a leadership role in addressing what we perceive to be a growing gap between the world of education and the world of work. If we are to improve the economic condition of our community, we must work in a consorted effort to close the gap between the technical skills that our citizens currently possess and those skills that are required for available careers. We must develop the types of career skills within our young people that are essential to success in the workforce, and we have to work together to develop the kind of thinking skills that will not only afford our students success within the current job market but will also grant them the capacity to adapt to the demands of such a rapidly changing economy. Our stu- dents will undoubtably be confronted with perplexing problems and unprecedented challenges within their lifetime. If we are to meet such challenges, then we are going to need the contributions of all of our young people. -

Music & Entertainment Auction

Hugo Marsh Neil Thomas Plant (Director) Shuttleworth (Director) (Director) Music & Entertainment Auction 20th February 2018 at 10.00 For enquiries relating to the sale, Viewing: 19th February 2018 10:00 - 16:00 Please contact: Otherwise by Appointment Saleroom One, 81 Greenham Business Park, NEWBURY RG19 6HW Telephone: 01635 580595 Christopher David Martin David Howe Fax: 0871 714 6905 Proudfoot Music & Music & Email: [email protected] Mechanical Entertainment Entertainment www.specialauctionservices.com Music As per our Terms and Conditions and with particular reference to autograph material or works, it is imperative that potential buyers or their agents have inspected pieces that interest them to ensure satisfaction with the lot prior to the auction; the purchase will be made at their own risk. Special Auction Services will give indica- tions of provenance where stated by vendors. Subject to our normal Terms and Conditions, we cannot accept returns. Buyers Premium: 17.5% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 21% of the Hammer Price Internet Buyers Premium: 20.5% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 24.6% of the Hammer Price Historic Vocal & other Records 9. Music Hall records, fifty-two, by 16. Thirty-nine vocal records, 12- Askey (3), Wilkie Bard, Fred Barnes, Billy inch, by de Tura, Devries (3), Doloukhanova, 1. English Vocal records, sixty-three, Bennett (5), Byng (3), Harry Champion (4), Domingo, Dragoni (5), Dufranne, Eames (16 12-inch, by Buckman, Butt (11 - several Casey Kids (2), GH Chirgwin, (2), Clapham and inc IRCC20, IRCC24, AGSB60), Easton, Edvina, operatic), T Davies(6), Dawson (19), Deller, Dwyer, de Casalis, GH Elliot (3), Florrie Ford (6), Elmo, Endreze (6) (39, in T1) £40-60 Dearth (4), Dodds, Ellis, N Evans, Falkner, Fear, Harry Fay, Frankau, Will Fyfe (3), Alf Gordon, Ferrier, Florence, Furmidge, Fuller, Foster (63, Tommy Handley (5), Charles Hawtrey, Harry 17. -

Dec. 22, 2015 Snd. Tech. Album Arch

SOUND TECHNIQUES RECORDING ARCHIVE (Albums recorded and mixed complete as well as partial mixes and overdubs where noted) Affinity-Affinity S=Trident Studio SOHO, London. (TRACKED AND MIXED: SOUND TECHNIQUES A-RANGE) R=1970 (Vertigo) E=Frank Owen, Robin Geoffrey Cable P=John Anthony SOURCE=Ken Scott, Discogs, Original Album Liner Notes Albion Country Band-Battle of The Field S=Sound Techniques Studio Chelsea, London. (TRACKED AND MIXED: SOUND TECHNIQUES A-RANGE) S=Island Studio, St. Peter’s Square, London (PARTIAL TRACKING) R=1973 (Carthage) E=John Wood P=John Wood SOURCE: Original Album liner notes/Discogs Albion Dance Band-The Prospect Before Us S=Sound Techniques Studio Chelsea, London. (PARTIALLY TRACKED. MIXED: SOUND TECHNIQUES A-RANGE) S=Olympic Studio #1 Studio, Barnes, London (PARTIAL TRACKING) R=Mar.1976 Rel. (Harvest) @ Sound Techniques, Olympic: Tracks 2,5,8,9 and 14 E= Victor Gamm !1 SOUND TECHNIQUES RECORDING ARCHIVE (Albums recorded and mixed complete as well as partial mixes and overdubs where noted) P=Ashley Hutchings and Simon Nicol SOURCE: Original Album liner notes/Discogs Alice Cooper-Muscle of Love S=Sunset Sound Recorders Hollywood, CA. Studio #2. (TRACKED: SOUND TECHNIQUES A-RANGE) S=Record Plant, NYC, A&R Studio NY (OVERDUBS AND MIX) R=1973 (Warner Bros) E=Jack Douglas P=Jack Douglas and Jack Richardson SOURCE: Original Album liner notes, Discogs Alquin-The Mountain Queen S= De Lane Lea Studio Wembley, London (TRACKED AND MIXED: SOUND TECHNIQUES A-RANGE) R= 1973 (Polydor) E= Dick Plant P= Derek Lawrence SOURCE: Original Album Liner Notes, Discogs Al Stewart-Zero She Flies S=Sound Techniques Studio Chelsea, London. -

Bowling Green Alumni Association Announces

THE AREA’S ONLY LOCALLY-OWNED & OPERATED NEWSPAPER | EST. OCTOBER 1, 1996 HE EOPLE S RIBUNE TNEWS FOR PIKEP, EASTERN AUDRAIN’& NORTHERNT LINCOLN COUNTIES FREE Published Every Tuesday • Vol. 26 - No. 42 • Tuesday, Aug. 3, 2021 • Online at www.thepeoplestribune.com Bowling Green Alumni Association Announces BanquetBY BRICE Speaker,CHANDLER EntertainmentLynyrd Skynyrd, The Allman Broth- STAFF WRITER ers, The Dave Matthews Band, and First held in 1985, the Bowling more. Green Alumni Association hosts its According to his bio, “Powell's annual alumni banquet each fall to work has been included on multiple honor graduating classes of the past gold and platinum records with nine and celebrate the education and different Grammy winning proj- memories of those important years ects.” at Bowling Green High School. Not only has he worked on such The organization also updates notable projects, but Powell has also members on one of its founding pur- cut vinyl records for the last 13- poses – the status of scholarships years with the Sam Phillips Record- awarded each year to graduating ing Service and his own company, seniors. Take Out “To date, Vinyl. the association Powell met has awarded his wife of 28- more than years, Susan, $411,050 in during a scholarships,” recording ses- the group sion at Ardent stated in its re- Studios for a cent banquet new band registration called The form. “Includ- Mother Sta- ing eighteen tion. $1,000 schol- When not Hot Weather arships to in the studio, 2020 gradu- “he remains a ates and six- diehard Saint teen $1,000 Louis Cardi- Did Not Deter scholarships to nals fan.” 2021 gradu- Attendees ates.” of this year's To celebrate banquet will Pike County Fair the accom- also be treated plishment and camaraderie, the as- to entertainment from an alumni sociation invites special guest choir under the direction of retired speakers and entertainers for a night vocal music instructor, Jack Bibb. -

2014 Annual Report and Spring 2015 Newsletter

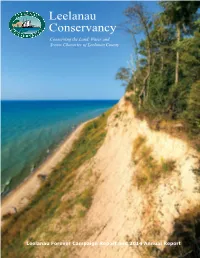

Leelanau Conservancy Conserving the Land, Water and Scenic Character of Leelanau County Leelanau Forever Campaign Report and 2014 Annual Report Thoughts From Our Chairman Susan continues to help us as we seek to fill her role. We will not find another Susan, just as we did not find another Brian. Tom Nelson, our new Executive Director, will lead us into the future, using his own talents, his love of Leelanau, his passion for the mission of our Conservancy, his concerns for the people of Leelanau. This is a fecund beginning for Tom, for the Conservancy, for our Leelanau. As we reflect on the past and look to the future, I am so grateful to you, our members, our supporters. Without you, nothing our Conservancy did would have been done, and nothing our Conservancy wants to do will be done. I thank you, Leelanau thanks you. You make our Conservancy possible. ooking back over last year I see endings - beautiful Lendings, each one of which is at once an ending Larry Mawby and also a beginning - promising beginnings which will Chairman of the Board carry our Conservancy into the future. The Leelanau Forever Campaign, begun five years ago, was successfully completed at the end of 2014. Because of your generous support, our Conservancy What’s Inside was able to protect natural lands and farmlands here in Leelanau, lands that will sustain future generations. The Leelanau Forever Campaign Page 4-19 deferred gifts pledged during the campaign [which our Campaign Summary Page 4-5 Conservancy will receive over the next three decades] Natural Lands protected Page 6-7 will help us steward those precious lands, helping us fulfill our obligations to those future generations. -

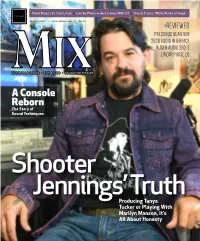

A Console Reborn the Story of Sound Techniques

David Broza’s En Casa Limon ★ Live By Phone ★ Here Comes MIDI 2.0 ★ Classic Tracks: ‘White Punks on Dope’ August 2020 \\ mixonline.com \\ $6.99 >REVIEWED PRESONUS QUANTUM 2626 AUDIO INTERFACE NUGEN AUDIO SEQ-S LINEAR PHASE EQ MUSIC PRODUCTION ! LIVE SOUND ! SOUND FOR PICTURE A Console Reborn The Story of Sound Techniques Shooter Jennings’ Truth Producing Tanya Tucker or Playing With Marilyn Manson, It’s All About Honesty Resurrection of a Console Danny White, Geoff Frost and the Legend of Sound Techniques By Steve Harvey hat signi!icant piece of audio Frost set up a workshop upstairs and began to equipment is common to “Hey, hand-build custom consoles for the likes of De W Jude,” several tracks off the White Lane Lea Kingsway and Trident Studios, while Album and a slew of career-de!ining LPs from Wood ran the studio below. When the red light the likes of David Bowie, Queen, Elton John, The went on in the workshop Frost and crew would Doors, Deep Purple, Genesis, The Rolling Stones set down tools until the end of the take. and Nick Drake? It wasn’t long before Tutti Camarata at Sunset While you think about that, let me tell you Sound Recorders in Hollywood heard about the a story. Sound Techniques A Range and ordered one to In late 1964, Geoff Frost and John Wood, two enable his facility to work in the new 8-track staff engineers working at Levy's Sound Studio format. Installed in April 1967, the desk was in London, decided to quit and open their own the !irst British-designed mixing desk ever sold recording studio after the giant U.S. -

Glam Rock by Barney Hoskyns 1

Glam Rock By Barney Hoskyns There's a new sensation A fabulous creation, A danceable solution To teenage revolution Roxy Music, 1973 1: All the Young Dudes: Dawn of the Teenage Rampage Glamour – a word first used in the 18th Century as a Scottish term connoting "magic" or "enchantment" – has always been a part of pop music. With his mascara and gold suits, Elvis Presley was pure glam. So was Little Richard, with his pencil moustache and towering pompadour hairstyle. The Rolling Stones of the mid-to- late Sixties, swathed in scarves and furs, were unquestionably glam; the group even dressed in drag to push their 1966 single "Have You Seen Your Mother, Baby, Standing in the Shadow?" But it wasn't until 1971 that "glam" as a term became the buzzword for a new teenage subculture that was reacting to the messianic, we-can-change-the-world rhetoric of late Sixties rock. When T. Rex's Marc Bolan sprinkled glitter under his eyes for a TV taping of the group’s "Hot Love," it signaled a revolt into provocative style, an implicit rejection of the music to which stoned older siblings had swayed during the previous decade. "My brother’s back at home with his Beatles and his Stones," Mott the Hoople's Ian Hunter drawled on the anthemic David Bowie song "All the Young Dudes," "we never got it off on that revolution stuff..." As such, glam was a manifestation of pop's cyclical nature, its hedonism and surface show-business fizz offering a pointed contrast to the sometimes po-faced earnestness of the Woodstock era. -

Tourism Risk, Crisis and Recovery Management Guide

Tourism Risk, Crisis and Recovery Management Guide E Version “Chance favours the prepared mind.“ - Louis Pasteur www.cato.asn.au 1 © David Beirman 2016 CONTENTS P 3 Introduction to the CATO Guide P 4 Part 1 Defining a Tourism Crisis for Wholesalers PP 4-12 Part 2 Focus on Risk Management and Security PP 13-19 Part 3 Effective Tourism Crisis Management PP 20-22 Part 4 Crisis Management Template for Wholesale Tour Operators PP 23-25 Part 5 Ten Point Post Crisis Business Market Recovery Guide PP 26-29 Part 6 Tourism Recovery from Security Related Issues with a Focus on Media Relations PP 30-31 Part 7 Highlighting Social Media PP 32-33 Part 8 Resources and References for Risk, Crisis and Recovery in Tourism PP 34-36 Appendix 1 Ranking the Severity of Tourism related Crises P 37 Appendix 2 Quick Risk Management Template for CATO members Prepared for the Council of Australian Tour Operators by : ©Dr David Beirman 2016– Management Discipline Group Tourism, UTS Business School University of Technology-Sydney with material contributed by Bert Van Walbeek and Ken Scott ISBN 978-0-9945587-1-8 For: Council of Australian Tour Operators 2 © David Beirman 2016 Introduction to the CATO Guide CATO members whether wholesalers or national tourist offices, are often in the front line of tourism crisis events. Almost half the tourists who book international trips from Australia will use the services of wholesalers for at least part of their travel itinerary. All tourists who travel internationally place a degree of reliance on destination management organisations through their offices or their websites along with wholesalers and travel agents to let them know about the risks which may apply to visiting their chosen destination. -

In the Shop Ken Scott

THE HOBBS METER THE RVATOR SECOND ISSUE 20099 6,175 COMPLETED RVS A beautiful RV-9A, built in The Netherlands by Rens Verhoeven. Now, this just begs for a caption contest! Van’s engineer Rian Johnson flew his own RV-7A to Sun ‘n Fun and this happened. Send us your best caption, preferably in an e-mail with ‘caption contest’ in the header. The winner gets a pair of Van’s hats, autographed by Van himself. The decision of the judges, however capricious, arbitrary or unpredictable, is final. Grant Krueger took this photo at Mandeville, on the South Island of New Zealand. I think I know what it is... or will be. What’s your guess? 2 COOL MACHINES AT VAN’S KEN SCOTT When you say “cool ma- chines at Van’s” everyone who’s had a shop tour imme- diately thinks of the big punch presses whacking their way through miles of aluminum sheet, changing bits on the fly and punching hole patterns accurate to a couple thou- sandths of an inch. Punch presses are pretty high on the “cool” scale, but there are quite a few other machines in our production shop that score just as well. Some of them are big and bolted to the floor, some of them are small and hide under benches until they’re needed, but all them allow us to do very specific jobs quickly and accurately. Here’s a look around. ABRASIVE PLANER The big, black, cubical beast in the center of the floor is an abrasive planer. It’s es- Above: it may not be beautiful now, but you should have seen sentially a big sanding drum it when we got it. -

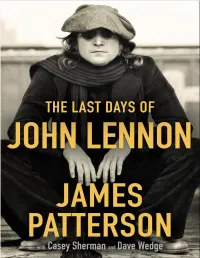

The Last Days of John Lennon

Copyright © 2020 by James Patterson Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce creative works that enrich our culture. The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights. Little, Brown and Company Hachette Book Group 1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104 littlebrown.com twitter.com/littlebrown facebook.com/littlebrownandcompany First ebook edition: December 2020 Little, Brown and Company is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Little, Brown name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher. The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591. ISBN 978-0-316-42907-8 Library of Congress Control Number: 2020945289 E3-111020-DA-ORI Table of Contents Cover Title Page Copyright Dedication Prologue Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5 — Chapter 6 Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Chapter 9 Chapter 10 Chapter 11 Chapter 12 Chapter 13 Chapter 14 Chapter 15 Chapter 16 Chapter 17 Chapter 18 — Chapter 19 Chapter 20 Chapter 21 Chapter 22 Chapter 23 Chapter 24 -

Aladdin Sane

Aladdin Sane Aladdin Sane 1 / 2 The follow-up to the hugely successful Ziggy Stardust album, Aladdin Sane found David Bowie experimenting with a range of new musical styles, and reflected .... Aladdin Sane. Design/Artwork: Brian Duffy, Celia Philo, Philip Castle Photography: Brian Duffy Released: April 1973. Label: RCA Producers: Ken Scott, David .... Live versions of all but "The Prettiest Star" and "Lady Grinning Soul" have been released on various discs including Ziggy Stardust: The Motion Picture, David Live and Aladdin Sane – 30th Anniversary. "The Jean Genie" is the only song on the album that Bowie played in concert throughout his career.. Why Aladdin Sane Is David Bowie's Most Important Album. ______. THIS is one of those pieces that is not provoked by…. ClashMusic: Classic Album, Recorded in London and New York in 1973 to a backdrop of infidelity and egotism, 'Aladdin Sane' saw David .... "Aladdin Sane (1913–1938–197?)" is a song by David Bowie, the title track from his 1973 album Aladdin Sane. Described by biographer David Buckley as the .... Aladdin Sane makes me think of Queen and Freddie Mercury's stage presence, as well as Marlene Dietrich in Blue Angel. I would listen to this album while:.. If by conventional lights Bowie is a lad insane, then as an Aladdin, a conjurer of supernatural forces, he is quite sane. The titles may change from .... The second most important moment in Bowie's glam period, Aladdin Sane is full of smart, cutting-edge songs that hold up decades later as classic moments in .... Like The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders From Mars, Aladdin Sane was co-produced by Bowie and Ken Scott at London's Trident ... -

Guitarist Magazine

WIN! A JACKSON QUILT-TOP SOLOIST ELECTR IC INSIDE Issue 404 MARCH 2016 COLLE C TOR’S E DITION The Stories Behind The Riffs FEATURING FIRST PLAY CARLOS ALOMAR MICK RONSON A ‘Real’ Gretsch NILE RODGERS for under £400? EARL SLICK p98 & MORE... Recording His Final Album Future Publishing Limited, Quay House, The Ambury, Bath, BA1 1UA Telephone 01225 442244 Email [email protected] Online www.guitarist.co.uk Changes Like many others, I think everyone at Guitarist had more or less considered David Bowie to be immortal. Likewise, Lemmy seemed too much a part of rock’s scenery to leave us so soon. As we went to press with this issue, we also learned the sad news that Eagles co-founder Glenn Frey had passed (look out for a full tribute next month), making this winter the worst in memory for losing legends. The only very slight consolation for all this is that it prompted us to listen again to the music that made them household names. In the case of Bowie, it was a reminder of the astonishing breadth and ambition of his music-making (see cover feature, p76). Rightly regarded as classic now, Bowie’s music must have been sensational when he was starting out – and I’m sure not everyone ‘got it’ at the time. Passing years have a habit of making the new and strange in music feel comfortably familiar, and finally classic. That thought has been a reminder of the importance of seeking out uncommon sounds, and not just sticking to your comfort zone of old favourites.