Design Recline Modern Archit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bauhaus 1 Bauhaus

Bauhaus 1 Bauhaus Staatliches Bauhaus, commonly known simply as Bauhaus, was a school in Germany that combined crafts and the fine arts, and was famous for the approach to design that it publicized and taught. It operated from 1919 to 1933. At that time the German term Bauhaus, literally "house of construction" stood for "School of Building". The Bauhaus school was founded by Walter Gropius in Weimar. In spite of its name, and the fact that its founder was an architect, the Bauhaus did not have an architecture department during the first years of its existence. Nonetheless it was founded with the idea of creating a The Bauhaus Dessau 'total' work of art in which all arts, including architecture would eventually be brought together. The Bauhaus style became one of the most influential currents in Modernist architecture and modern design.[1] The Bauhaus had a profound influence upon subsequent developments in art, architecture, graphic design, interior design, industrial design, and typography. The school existed in three German cities (Weimar from 1919 to 1925, Dessau from 1925 to 1932 and Berlin from 1932 to 1933), under three different architect-directors: Walter Gropius from 1919 to 1928, 1921/2, Walter Gropius's Expressionist Hannes Meyer from 1928 to 1930 and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe Monument to the March Dead from 1930 until 1933, when the school was closed by its own leadership under pressure from the Nazi regime. The changes of venue and leadership resulted in a constant shifting of focus, technique, instructors, and politics. For instance: the pottery shop was discontinued when the school moved from Weimar to Dessau, even though it had been an important revenue source; when Mies van der Rohe took over the school in 1930, he transformed it into a private school, and would not allow any supporters of Hannes Meyer to attend it. -

The Design and Construction of Furniture for Mass Production

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Theses 5-30-1986 The design and construction of furniture for mass production Kevin Stark Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses Recommended Citation Stark, Kevin, "The design and construction of furniture for mass production" (1986). Thesis. Rochester Institute of Technology. Accessed from This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ROCHESTER INSTITUTE OP TECHNOLOGY A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The College of Fine and Applied Arts in Candidacy for the Degree of MASTER OF FINE ARTS The Design and Construction of Furniture for Mass Production By Kevin J. Stark May, 1986 APPROVALS Adviser: Mr. William Keyser/ William Keyser Date: 7 I Associate Adviser: Mr. Douglas Sigler/ Date: Douglas Sigler Associate Adviser: Mr. Craig McArt/ Craig McArt Date: U3{)/8:£ ----~-~~~~7~~------------- Special Assistant to the h I Dean for Graduate Affairs:Mr. Phillip Bornarth/ P i ip Bornarth Da t e : t ;{ ~fft, :..:..=.....:......::....:.:..-=-=-=...i~:...::....:..:.=-=..:..:..!..._------!..... ___ -------7~'tf~~---------- Dean, College of Fine & Applied Arts: Dr. Robert H. Johnston/ Robert H. Johnston Ph.D. Date: ------------------------------ I, Kevin J. Stark , hereby grant permission to the Wallace Memorial Library of RIT, to reproduce my thesis in whole or in part. Any reproduction will not be for commercial use or profit. Date : ____5__ ?_O_-=B::;..... 0.:.......-_____ CONTENTS Thesis Proposal i CHAPTER I - Introduction 1 CHAPTER II - An Investigation Into The Design and Construction Process Side Chair 2 Executive Desk 12 Conference Table 18 Shelving Unit 25 CHAPTER III - A Perspective On Techniques Used In Industrial Furniture Design Wood 33 Metals 37 Plastics 41 CHAPTER IV - Conclusion 47 CHAPTER V - Footnotes 49 CHAPTER VI - Bibliography 50 ILLUSTRATIONS Page I. -

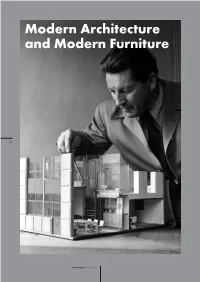

Modern Architecture and Modern Furniture

Modern Architecture and Modern Furniture 14 docomomo 46 — 2012/1 docomomo46.indd 14 25/07/12 11:13 odern architecture and Modern furniture originated almost during the same period of time. Modern architects needed furniture compatible with their architecture and because Mit was not available on the market, architects had to design it themselves. This does not only apply for the period between 1920 and 1940, as other ambitious architectures had tried be- fore to present their buildings as a unit both on the inside and on the outside. For example one can think of projects by Berlage, Gaudí, Mackintosh or Horta or the architectures of Czech Cubism and the Amsterdam School. This phenomenon originated in the 19th century and the furniture designs were usually developed for the architect’s own building designs and later offered to the broader consumer market, sometimes through specialized companies. This is the reason for which an agree- ment between the architect and the commissioner was needed, something which was not always taken for granted. By Otakar M á c ˆe l he museum of Czech Cubism has its headquarters designed to fit in the interior, but a previous epitome of De in the Villa Bauer in Liboˇrice, a building designed Stijl principles that culminated in the Schröderhuis. Tby the leading Cubist architect Jiˆrí Gocˆár between The chair was there before the architecture, which 1912 and 1914. In this period Gocˆár also designed Cub- was not so surprising because Rietveld was an interior ist furniture. Currently the museum exhibits the furniture designer. The same can be said about the “father” of from this period, which is not actually from the Villa Bauer Modern functional design, Marcel Breuer. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information C om pany 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 313 761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 9031153 The utilitarian object as appropriate study for art education: An historical and philosophical inquiry grounded in American and British contexts Sproll, Paul Anthony, Ph.D. -

Siegfried Bing's Salon De L'art Nouveau and the Dutch Gallery Arts and Crafts

Marjan Groot Siegfried Bing's Salon de L'Art Nouveau and the Dutch Gallery Arts and Crafts Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 4, no. 2 (Summer 2005) Citation: Marjan Groot, “Siegfried Bing's Salon de L'Art Nouveau and the Dutch Gallery Arts and Crafts,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 4, no. 2 (Summer 2005), http://www.19thc- artworldwide.org/summer05/214-siegfried-bings-salon-de-lart-nouveau-and-the-dutch- gallery-arts-and-crafts. Published by: Association of Historians of Nineteenth-Century Art Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. ©2005 Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide Groot: Siegfried Bing‘s Salon de L‘Art Nouveau and the Dutch Gallery Arts and Crafts Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 4, no. 2 (Summer 2005) Siegfried Bing's Salon de L'Art Nouveau and the Dutch Gallery Arts and Crafts by Marjan Groot On the 11th of August 1898 a Dutch gallery opened in The Hague under the English name Arts and Crafts (fig. 1). This was less than three years after Siegfried Bing had transformed his shop in Paris into the new and prestigious Salon de L'Art Nouveau. Important artist- designers in the Netherlands immediately recognized Arts and Crafts as the first Dutch gallery for contemporary decorative arts. The gallery presented handcrafted furniture, textiles, ceramics and metalwork of high quality alongside paintings and sculptures. Arts and Crafts only lasted until July 1904, whereas Bing's gallery closed in March 1905. But during the six years of its existence, the gallery played an important role in the world of Dutch applied arts by showing works by Dutch and foreign modern designers and by stimulating debate about the path the Dutch revival of the applied arts should take. -

Association De Gestion Du Site Cap Moderne Villa E-1027, Eileen Gray, 1929, Roquebrune- Cap-Martin, France Architect and Influe

Association de Gestion du Site Cap Moderne Villa E-1027, Eileen Gray, 1929, Roquebrune- Cap-Martin, France Architect and influential modern furniture designer Eileen Gray built Villa E-1027 between 1927 and 1929 on the shoreline of the Côte d’Azur in southern France. Conceived as a retreat and vacation home for Gray and architectural author and editor Jean Badovici, the Villa marries forward-thinking design principles with practical living. Following decades of environmental stress and several private owners, the building now belongs to Villa E-1027. Photo: Manuel Bougot the French Coastline Conservancy and is under www.manuelbougot.com 2016 the care of the non-profit Association Cap Moderne that is committed to its preservation. In 2016, the Getty Foundation awarded a planning grant that supported technical research into Villa E-1027’s reinforced concrete. This defining material of the building has suffered serious deterioration from exposure to sea air, rain and water runoff from the coastal slope. Once completed, the work will mark a crucial step forward in the long-term preservation of the Villa in its picturesque but challenging seaside environment. With thorough research and planning now in place, the building’s stewards are preparing to take informed action. A new Getty grant will support conservation of the Villa’s reinforced concrete and serve as a pilot for preserving concrete buildings with the use of impressed current cathodic protection or ICCP. Originally developed for sea vessels to prevent metal corrosion in wet conditions, the process runs a regulated flow of low-power electrical current through the metal rebar that reinforces the building’s concrete. -

ADAPTATIONS of TRADITIONAL FURNITURE in the CONTEMPORARY HOME: 1959-1969 Abstract Approved:Redacted for Privacy Joan Patterson

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF NANCY PANAK KWALLEK for the MASTER OF SCIENCE (Name) (Degree) Clothing, Textiles, June 24, 1969 in and Related Arts presented on (Major) (Date) Title: ADAPTATIONS OF TRADITIONAL FURNITURE IN THE CONTEMPORARY HOME: 1959-1969 Abstract approved:Redacted for Privacy Joan Patterson The purpose of this study was to investigate the revival trends in furniture design during the period 1959-1969, and to understand the relationship of these adaptations to contemporary cultural objectives. An understanding of the design characteristics from the originals to the modern derivatives is useful for those who wish to select good design within their income range.There is virtually no information readily available to the consumer relative to the appropriate selec- tion of adapted furniture designs for contemporary interiors. The problem is dealt with in five specific aspects:(1) to ascer- tain the influences that caused the adaptations of historical styles; (2) to analyze the dominant furniture designs and to determine whether they have been modified relative to authentic pieces, and if so, in what way; (3) to recognize the contemporary style; (4) to gain a perspective of the use of adaptations in contemporary interiors; and (5) to help establish a criterion on behalf of the consumer for better furniture selection. The information was obtained through the observation of general trends, not through a statistical method. A number of sources includ- ing newspaper and magazine articles, books, personal correspondence and furniture catalogs from individual manufacturing companies were studied. As a basis for analysis, a written description and photo- graphic evidence were used documenting the characteristics of the adaptations to their originals and to a contemporary composition. -

Architecture and Furniture: Aalto

Architecture and furniture: Aalto Author Museum of Modern Art (New York, N.Y.) Date 1938 Publisher [publisher not identified] Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/1802 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history— from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art LIBRARY THE OF MOOtftN AFtl mlmm - ARCHITECTURE AXD FURNITURE A ALTO THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART NEW YORK PvrcXx l V-t- hMA r COPYRIGHT, MARCH, 1938, BY THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK FOREWORD Six years ago when the Museum of Modern Art opened the first exhibi tion of modern architecture in this country, attention was focused on the fundamental qualities of the new "International Style." The work of Gropius, Mies van der Rohe, Oud, Le Corbusier and others was shown to have been conceived with a basically functionalist approach, and to have been carried out with a common set of esthetic principles. Since then, modern architecture has relinquished neither the func tionalist approach nor the set of esthetic principles, but both have been modified, particularly by the younger men who have since joined the established leaders. Among these none is more important than Aalto. Like the designs of other men first active in the '30's, Aalto's work, without ceasing in any way to be modern, does not look like the modern work of the '20's. The younger men employ new materials and new methods of construction, of course, but these only partly explain the change. -

INT 120 Modern Architecture and Furniture Style Comparison Assignment - 75 Points

GENERAL STUDIES COURSE PROPOSAL COVER FORM (ONE COURSE PER FORM) 1.) DATE: 11/30/17 2.) COMMUNITY COLLEGE: Maricopa Co. Comm. College District 3.) COURSE PROPOSED: Prefix: INT Number: 120 Title: Modern Architecture and Furniture Credits: 3 CROSS LISTED WITH: Prefix: Number: ; Prefix: Number: ; Prefix: Number: ; Prefix: Number: ; Prefix: Number: ; Prefix: Number: 4.) COMMUNITY COLLEGE INITIATOR: CYNTHIA PARKER PHONE: 602-285-7608 FAX: Email: [email protected] ELIGIBILITY: Courses must have a current Course Equivalency Guide (CEG) evaluation. Courses evaluated as NT (non-transferable are not eligible for the General Studies Program. MANDATORY REVIEW: The above specified course is undergoing Mandatory Review for the following Core or Awareness Area (only one area is permitted; if a course meets more than one Core or Awareness Area, please submit a separate Mandatory Review Cover Form for each Area). POLICY: The General Studies Council (GSC) Policies and Procedures requires the review of previously approved community college courses every five years, to verify that they continue to meet the requirements of Core or Awareness Areas already assigned to these courses. This review is also necessary as the General Studies program evolves. AREA(S) PROPOSED COURSE WILL SERVE: A course may be proposed for more than one core or awareness area. Although a course may satisfy a core area requirement and an awareness area requirement concurrently, a course may not be used to satisfy requirements in two core or awareness areas simultaneously, even if approved for those areas. With departmental consent, an approved General Studies course may be counted toward both the General Studies requirements and the major program of study. -

T. H. Robsjohn-Gibbings: Crafting a Modern Home for Postwar America

T. H. Robsjohn-Gibbings: Crafting a Modern Home for Postwar America Daniella Ohad Smith , Ph.D. 1 ABSTRACT Terence Harold Robsjohn-Gibbings (1905– 1976) was an architect, decorator, furniture designer, tastemaker, and thinker whose innovative ideas on interior design during the postwar era had a formative impact on American domestic culture. Through books, arti- cles, lectures, interior décor, and industrial design, he advanced a singular outlook on the modern home, rooted in Greco-Roman sensibilities, classical principles, and early American domestic culture. By considering his contribution to the emergence of middle- class American style during the formative years of modernism, I propose that although hardly discussed in the literature, Robsjohn-Gibbings had occupied a signifi cant role in steering popular taste away from Art Moderne and from the popular fashion of collect- ing European antiques and reproductions toward a genuine American modernism. A progressive thinker, he challenged international modernism and the postwar organic language through a scholarly understanding of ancient Greco-Roman furniture and a thorough study of American material culture. Introduction ing. Claiming that “American interiors should be visualized in terms of warmth, friendliness, and In 1965, at the age of sixty, the British-born designer comfort,” 2 he advised middle-class Americans on Terence Harold Robsjohn-Gibbings (1905 – 1976) how to develop a personal taste and “how to judge moved to Athens and settled in an apartment over- the modern.” 3 He was recognized as an important looking the Parthenon. This was a fi tting fi nal desti- advocate for simplicity and integrity in contemporary nation for his lifelong journey into the aesthetic design and was compared to such infl uential trendset- essence of classical Greece. -

The Museum of Modern Art's "What Is Modern?" Series, 1938-1969

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2012 The Museum of Modern Art's "What Is Modern?" Series, 1938-1969 Jennifer Tobias The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1933 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] i THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART’S WHAT IS MODERN? SERIES, 1938–1969 BY JENNIFER TOBIAS A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Art History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2012 ii © 2012 JENNIFER TOBIAS ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Art History in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Dr. Rosemarie Haag Bletter [Bletter sig] Date Chair of Examining Committee Dr. Kevin Murphy [EO sig] Date Executive Officer Dr. Rose-Carol Long Dr. Claire Bishop Dr. Mary Anne Staniszewski Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iv Abstract THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART’S WHAT IS MODERN? SERIES, 1938–1969 by Jennifer Tobias Adviser: Professor Rosemarie Haag Bletter Between 1938 and 1969, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) poses the question of What Is Modern? (WIM) in a series of books, traveling exhibitions, and a symposium. -

Battlelines E.1027

Battle Lines: E.1027 Beatriz Colomina What the word for space, Raum, Rum, designates is said by its ancient meaning. Raum means a place cleared or freed for settlement and lodging. A space is something that has been made room for, something that is cleared and free, namely within a boundary, Greek peras. A boundary is not that at which something stops but, as the Greeks recognized, the boundary is that from which something begins its presencing. That is why the concept is that of horismos, that is, the horizon, the boundary. Space is in essence that for which room has been made, that which is let into its bounds. Martin Heidegger, “Building Dwelling Thinking,” Poetry, Language, Thought trans. Albert Hofstadter (New York: Harper and Row, 1971) The horizon is an interior (fig 1). It defines an in the city, of course, but also in all the technologies enclosure. In its familiar sense, it marks a limit to the that define the space of the city: the railroad, space of what can be seen, which is to say, it newspapers, photography, electricity, advertisements, organises this visual space into an interior. The reinforced concrete, glass and steel architecture, the horizon makes the outside, the landscape, into an telephone, film, radio, war. Each can be understood inside. How could that happen? Only if the “walls” as a mechanism that disrupts the older boundaries that enclose the space cease to be thought of between inside and outside, public and private, night (exclusively) as solid pieces of material, as stone and day, depth and surface, here and there, street walls, as brick walls.