Design of a CNC Routed Sheet Good Chair %A WY.7

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bauhaus 1 Bauhaus

Bauhaus 1 Bauhaus Staatliches Bauhaus, commonly known simply as Bauhaus, was a school in Germany that combined crafts and the fine arts, and was famous for the approach to design that it publicized and taught. It operated from 1919 to 1933. At that time the German term Bauhaus, literally "house of construction" stood for "School of Building". The Bauhaus school was founded by Walter Gropius in Weimar. In spite of its name, and the fact that its founder was an architect, the Bauhaus did not have an architecture department during the first years of its existence. Nonetheless it was founded with the idea of creating a The Bauhaus Dessau 'total' work of art in which all arts, including architecture would eventually be brought together. The Bauhaus style became one of the most influential currents in Modernist architecture and modern design.[1] The Bauhaus had a profound influence upon subsequent developments in art, architecture, graphic design, interior design, industrial design, and typography. The school existed in three German cities (Weimar from 1919 to 1925, Dessau from 1925 to 1932 and Berlin from 1932 to 1933), under three different architect-directors: Walter Gropius from 1919 to 1928, 1921/2, Walter Gropius's Expressionist Hannes Meyer from 1928 to 1930 and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe Monument to the March Dead from 1930 until 1933, when the school was closed by its own leadership under pressure from the Nazi regime. The changes of venue and leadership resulted in a constant shifting of focus, technique, instructors, and politics. For instance: the pottery shop was discontinued when the school moved from Weimar to Dessau, even though it had been an important revenue source; when Mies van der Rohe took over the school in 1930, he transformed it into a private school, and would not allow any supporters of Hannes Meyer to attend it. -

The Design and Construction of Furniture for Mass Production

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Theses 5-30-1986 The design and construction of furniture for mass production Kevin Stark Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses Recommended Citation Stark, Kevin, "The design and construction of furniture for mass production" (1986). Thesis. Rochester Institute of Technology. Accessed from This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ROCHESTER INSTITUTE OP TECHNOLOGY A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The College of Fine and Applied Arts in Candidacy for the Degree of MASTER OF FINE ARTS The Design and Construction of Furniture for Mass Production By Kevin J. Stark May, 1986 APPROVALS Adviser: Mr. William Keyser/ William Keyser Date: 7 I Associate Adviser: Mr. Douglas Sigler/ Date: Douglas Sigler Associate Adviser: Mr. Craig McArt/ Craig McArt Date: U3{)/8:£ ----~-~~~~7~~------------- Special Assistant to the h I Dean for Graduate Affairs:Mr. Phillip Bornarth/ P i ip Bornarth Da t e : t ;{ ~fft, :..:..=.....:......::....:.:..-=-=-=...i~:...::....:..:.=-=..:..:..!..._------!..... ___ -------7~'tf~~---------- Dean, College of Fine & Applied Arts: Dr. Robert H. Johnston/ Robert H. Johnston Ph.D. Date: ------------------------------ I, Kevin J. Stark , hereby grant permission to the Wallace Memorial Library of RIT, to reproduce my thesis in whole or in part. Any reproduction will not be for commercial use or profit. Date : ____5__ ?_O_-=B::;..... 0.:.......-_____ CONTENTS Thesis Proposal i CHAPTER I - Introduction 1 CHAPTER II - An Investigation Into The Design and Construction Process Side Chair 2 Executive Desk 12 Conference Table 18 Shelving Unit 25 CHAPTER III - A Perspective On Techniques Used In Industrial Furniture Design Wood 33 Metals 37 Plastics 41 CHAPTER IV - Conclusion 47 CHAPTER V - Footnotes 49 CHAPTER VI - Bibliography 50 ILLUSTRATIONS Page I. -

VET Job Guide

NSW Department of Education Carpenter and Joiner Carpenters and joiners love working their hands to construct, erect, install, and repair structures made of wood. You’ll get great satisfaction Will I get a job? out of seeing your finished work enliven a home or building. Moderate growth in this occupation is predicted, with 200 What carpenters and joiners do new jobs in Australia in the next four years, Carpenters and joiners use their broad knowledge of building methods and timbers to bringing the total to make, install, repair or renovate structures, fixtures and fittings. They work on residential 117,800. and commercial projects constructing buildings, ships, bridges or concrete formwork, and in maintenance roles in factories, hospitals, institutions, and homes. What will I earn? On residential jobs, carpenters and joiners build the house framework, walls, roof frame, $951–$1,100 median and exterior finish. They install doors, windows, flooring, cabinets, stairs, handrails, full-time weekly salary panelling, moulding, and ceiling tiles. On commercial construction jobs, they build (before tax, excluding concrete forms, scaffolding, bridges, trestles, tunnels, shelters, towers or repair and super). maintain existing structures. Shop fitter, joiners, fixers or finish carpenters create wood furniture, window and door fittings, parquet floors and stairs for new homes and renovation projects. They may also create and sell their own furniture. Joiners are mostly based in workshops while carpenters often travel between sites until each job is completed. Carpenters may work as subcontractors employed by building and construction companies or are self-employed. education.nsw.gov.au NSW Department of Education You’ll like this job if… Roles to look for You enjoy creating things with your hands. -

Creating a Timber Frame House

Creating a Timber Frame House A Step by Step Guide by Brice Cochran Copyright © 2014 Timber Frame HQ All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the author. ISBN # 978-0-692-20875-5 DISCLAIMER: This book details the author’s personal experiences with and opinions about timber framing and home building. The author is not licensed as an engineer or architect. Although the author and publisher have made every effort to ensure that the information in this book was correct at press time, the author and publisher do not assume and hereby disclaim any liability to any party for any loss, damage, or disruption caused by errors or omissions, whether such errors or omissions result from negligence, accident, or any other cause. Except as specifically stated in this book, neither the author or publisher, nor any authors, contributors, or other representatives will be liable for damages arising out of or in connection with the use of this book. This is a comprehensive limitation of liability that applies to all damages of any kind, including (without limitation) compensatory; direct, indirect or consequential damages; income or profit; loss of or damage to property and claims of third parties. You understand that this book is not intended as a substitute for consultation with a licensed engineering professional. Before you begin any project in any way, you will need to consult a professional to ensure that you are doing what’s best for your situation. -

Modern Architecture and Modern Furniture

Modern Architecture and Modern Furniture 14 docomomo 46 — 2012/1 docomomo46.indd 14 25/07/12 11:13 odern architecture and Modern furniture originated almost during the same period of time. Modern architects needed furniture compatible with their architecture and because Mit was not available on the market, architects had to design it themselves. This does not only apply for the period between 1920 and 1940, as other ambitious architectures had tried be- fore to present their buildings as a unit both on the inside and on the outside. For example one can think of projects by Berlage, Gaudí, Mackintosh or Horta or the architectures of Czech Cubism and the Amsterdam School. This phenomenon originated in the 19th century and the furniture designs were usually developed for the architect’s own building designs and later offered to the broader consumer market, sometimes through specialized companies. This is the reason for which an agree- ment between the architect and the commissioner was needed, something which was not always taken for granted. By Otakar M á c ˆe l he museum of Czech Cubism has its headquarters designed to fit in the interior, but a previous epitome of De in the Villa Bauer in Liboˇrice, a building designed Stijl principles that culminated in the Schröderhuis. Tby the leading Cubist architect Jiˆrí Gocˆár between The chair was there before the architecture, which 1912 and 1914. In this period Gocˆár also designed Cub- was not so surprising because Rietveld was an interior ist furniture. Currently the museum exhibits the furniture designer. The same can be said about the “father” of from this period, which is not actually from the Villa Bauer Modern functional design, Marcel Breuer. -

Measurement and Modeling of the In-Plane Permeability of Oriented Strand-Based Wood Composites

MEASUREMENT AND MODELING OF THE IN-PLANE PERMEABILITY OF ORIENTED STRAND-BASED WOOD COMPOSITES by Chao Zhang B.Sc., Tsinghua University, 2006 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUiREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (Forestry) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) April 2009 © Chao Zhang, 2009 Abstract The objective of this research is to investigate the effects of panel density and air flow direction on the in-plane permeability of oriented strand-based wood composites. In- plane permeability is a key factor governing the energy consumption and pressing time during manufacture. The result is expected to provide information which could potentially reduce the pressing time. The thick, oriented strand boards of five densities were made of aspen (Populus tremuloides), and pressed in the laboratory. The production procedure yielded a uniform vertical density profile and good strand orientation. The specimens were sealed in a specially designed specimen holder and connected to a permeability measurement apparatus. The permeability values in parallel, perpendicular, and 45° to the strand orientation were obtained. The results showed that permeability values decreased rapidly as the density increased. The permeability was highest in the parallel-to-strand direction, and lowest in the perpendicular-to-strand direction. The permeability value in 45° direction was between the values of parallel- and perpendicular-to-strand directions. A polynomial equation was fitted to the results and an R2 was between 0.93 8 and 0.993. To examine the void structure changes during the densification, microscopic techniques were employed. Microscopic slides for each density level were prepared with a typical method widely used for petrography, and then investigated with a fluorescence microscope. -

Allison Lumber Company Collection

Allison Lumber Company Collection Evan F. Allison (1865 - 1937). In the management of his lands he led the way in Alabama to profitable forest conservation through selective tree cutting and reforestation. He restored species of wildlife indigenous to the area and taught methods for their conservation. - Alabama Hall of Fame, 1961. Although born to a family of limited resources, Evan Allison, with Steve Smith, and a third partner, R.C. Derby (also of Sumter County), established the Allison Lumber Company at Bellamy, AL in 1899. Bellamy was founded as a sawmill town. It was home to Sumter County’s first hospital which was established by the Allison Lumber Company. In 1903, the lumber company built a small frame structure near the site of the hospital to be used as a school (and a church on Sundays). Allison Lumber hired and paid the teachers. Over many decades, Mr. Allison guided the company to a position of leadership in the pine and hardwood industries. He was widely respected and solicited to run for Governor, but he declined. He gained control of wide timber interests and took an active part in the economic development of the state. This collection provides excellent documentation about how a successful business was run in the rural South during the nineteen twenties; banking; job applications; correspondence with the most influential people in the state; World War I restrictions on businesses; the fight to establish wildlife conservation; social customs including the hosting of the elaborate annual hunt – a combination of politics and recreation. Collection Span: Bulk of materials from 1917 - 1927 (History and 2 postcards from the 1960s.) (Cancelled checks from 1898 - 1938.) Size: 2 cu. -

Construction Specification ROUGH CARPENTRY Home Depot No

Section 06100 Construction Specification ROUGH CARPENTRY PART 1 - PART 1 - GENERAL 1.01 SUMMARY A. Extent of rough carpentry work is indicated on drawings and includes, but is not limited to, the following: 1. Miscellaneous wood framing 2. Wood nailers or blocking 3. Plywood (Fire Retardant Treated) 4. Oriented Strand Boards (OSB) B. All interior wood used for construction shall be fire retardant treated. C. All wood in roof construction and non-load bearing wall where the fire resistance rating is 1 hour or less, shall be fire resistant treated wood where required by code D. Related work specified elsewhere includes but may not be limited to: 1. Section 01012 - Preferred Purchasing 2. Section 06402: Interior Architectural Woodwork 1.02 PREFERRED PURCHASING A. Unless noted otherwise, Contractor and all subcontractors are encouraged to purchase all products listed in this specification section from a local The Home Depot Store. For more information, refer to Section 01012. 1.03 PRODUCT HANDLING A. Delivery and Storage: Keep materials under cover and dry. Protect against exposure to weather and contact with damp or wet surfaces. Stack lumber as well as plywood and other panels; provide for air circulation within and around stacks and under temporary coverings including polyethylene and similar materials. 1. For lumber and plywood pressure treated with waterborne chemicals, sticker between each course to provide air circulation. 1.04 PROJECT CONDITIONS A. Coordination: Fit carpentry work to other work; scribe and cope as required for accurate fit. Correlate location of furring, nailers, blocking, grounds and similar supports to allow attachment of other work. -

Cheery Cherry Toy Chest Download

Cheery Cherry Toy Chest A challenging classic that will last a lifetime We call this a toy chest—but it’s a book case, a knickknack box and a fun place to sit and read. And when your kids are grown, it makes one heck of a fne entry bench. Tis is one of the more challenging projects in the book. It involves biscuit joints, sunken panels and cutting tight curves. Plus, it’s made from cherry— a mistake in this material costs three times as much as a mistake in pine! So, if you’re a beginner, consider sharpening your chops on a couple of other projects before digging into this one. We show two versions of the fnished chest. One with cherry plywood panels; another with panels 18 | building unique and useful kids’ furniture 36" 1/4" 2 1/2" M 15" P R 11 1/4" 1 1/2" Q 15" 36" Top Side 1 1/4" 33" 1 1/2" 36" 9" E 1/4" 36" 1/4" 2 1/2" M F 2 1/2" M 1 1/2" D X 4 3/4" M 3/4" 15" H 15" 5 1/2" 3 1/2" 11 1/4" P R P 11 1/4" B 2 1/2" 24 1/2" R 11 1/4" 1 1/2" 24 1/2" Q 1 1/2" Q Seat T C 18 1/2" 12" U 9" U 16" W 10 1/8" V J K S 9" Front 15" 36" A 3 1/2" D 3 1/2" 15" 36" 1 1/4" 33" G 1 1/2" 1 1/4" 9" 33" E 1 1/2" 4" 9" O 1 1/2" E 1 1/2" 1" 1 1/2" 3/4" N L 3/4" 36" 33" F 1 1/2" F 37 1/2" 1 1/2" D X 4 3/4" D X 4 3/4" M 3/4" H 3/4" M 5 1/2" 36" H 3 1/2" 5 1/2" 3 1/2" 1/4" 11 1/4" B 2 1/2" 24 1/2" 11 1/4" B 2 1/2" 24 1/2" 24 1/2" 24 1/2" Seat 2 1/2" M T C 18 1/2" Seat 12" T C 18 1/2" 12" U 9" U 16" W 10 1/8" V J U 9" U 16" W 10 1/8" K V J S 9" K 15" S 9" P R 11 1/4" 1 1/2" Q A 3 1/2" D 3 1/2" A 3 1/2" D 3 1/2" G G 4" O 1 1/2" 1 1/2" 1" 4" 1 1/2" 3/4" O 1 1/2" 1 -

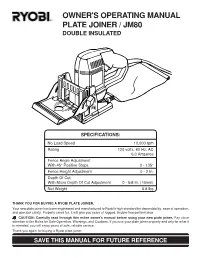

Owner's Operating Manual Plate Joiner / Jm80 Double Insulated

OWNER'S OPERATING MANUAL PLATE JOINER / JM80 DOUBLE INSULATED SPECIFICATIONS: No Load Speed 10,000 rpm Rating 120 volts, 60 Hz, AC 6.0 Amperes Fence Angle Adjustment With 45° Positive Stops 0 - 135° Fence Height Adjustment 0 - 2 In. Depth Of Cut With Micro Depth Of Cut Adjustment 0 - 5/8 In. (16mm) Net Weight 6.8 lbs THANK YOU FOR BUYING A RYOBI PLATE JOINER. Your new plate joiner has been engineered and manufactured to Ryobi's high standard for dependability, ease of operation, and operator safety. Properly cared for, it will give you years of rugged, trouble-free performance. CAUTION: Carefully read through this entire owner's manual before using your new plate joiner. Pay close attention to the Rules for Safe Operation, Warnings, and Cautions. If you use your plate joiner properly and only for what it is intended, you will enjoy years of safe, reliable service. Thank you again for buying a Ryobi plate joiner. SAVE THIS MANUAL FOR FUTURE REFERENCE Table of Contents 1. Table of Contents / Introduction ...............................................................2 2. Rules For Safe Operation ..................................................................... 4-6 3. Features ................................................................................................ 7-8 4. Adjustments .........................................................................................9-10 5. Operation...........................................................................................11-16 6. Maintenance ......................................................................................17-19 -

Wire Installation Guide

Wire Storage System Installation Guide P0-11Z8-P0 Tools Before you begin, there are several tools you will need for proper installation: Drill (Cordless is recommended) 1/4" Drill Bit Level Hammer Pencil Tape Measure Phillips Screw Bit (#2) Torpedo Level Pliers Stud Finder Standard Shelf Heights Shelf Type Installation height Single Wardrobe 68" above the floor Double Hanging System Top Shelf – 84" above the floor Lower shelf – 42" above the floor Stack of 5 Shelves 16", 29", 42", 55" and 68" above the floor (13" apart) Shoe Shelf 12" above the floor Removal of Drive Pins To remove pins on Wall Anchors, Brackets, and Back Clips, grab circular head of drive pin with a pair of pliers, turn one-half turn. Release hold of drive pin, grab the drive pin again and pull pin straight out towards you. This procedure will deactivate the molly, then the hardware piece can be easily removed from the wall. Open End to Open End Universal Shoe Shelf Used with 12" TightMesh® or Linen Shelf Installation 1. Mark 2-1/2" from end of desired shelf location. Using a level,make a mark on the back wall no more than every 12" – stop 2-1/2" from end of shelf. Installation 2. Using a 1/4" drill bit, drill all marks. 1. Rest shelf on front edge on the floor and flush against the wall, make marks 2" in from both ends. 3. Install the Back Clips by pushing them flush to the Also locate & mark studs along the shelf length. wall. Set drive pins. -

Introduction to Door Construction

Entry Door Construction Made Simple with Freud’s Entry & Interior Door Router Bit System Congratulations on your purchase of Freud’s Entry & Interior Door Router Bit System. This unique set allows you to build high quality 1-3/4” thick exterior doors or 1-3/8” thick interior doors, plus beautiful sidelights and transoms in almost any size or style. In this poster, you’ll find information on: door construction; planning & preparation; materials & safety; milling your parts; routing your rails, stiles, profiles & joints; and installation. Introduction to Door Construction Door units may consist of a number of elements. As shown in Figure 1, the unit will include the hinged door, sometimes called the “door panel,” and may include one or two sidelights to flank the door. Some units also include a transom above the door and sidelights. Here are some other common terms that will be used throughout these instructions: - Stiles: The vertical frame components of the door, sidelight or transom. - Rails: The horizontal frame components of Rails the door, sidelight or transom. - Center Stile: A vertical divider located between the stiles of Decorative the door. Glass - Raised Panel: A flat wooden section with Stiles routed edges fitted into slots in the stiles and Mortise rails. & Tenon Joint - Tenon: An extended piece of wood on the end of a rail that fits Raised into a pocket, or Panels “mortise” in the stile. Center - Mortise: A pocket cut Stile in a stile that matches the tenon on the end of a rail. Figure 1 Page 1 of 17 Materials Required In addition to the Freud Entry & Interior Door router bits, you will need the following tools and supplies to build your door unit: - Raised Panel Router Bit for profiling wooden raised panels.