Oil Shale Booklet 2015-01-11

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heartlands of Fife Visitor Guide

Visitor Guide Heartlands of Fife Heartlands of Fife 1 The Heartlands of Fife stretches from the award-winning beaches of the Firth of Forth to the panoramic Lomond Hills. Its captivating mix of bustling modern towns, peaceful villages and quiet countryside combine with a proud history, exciting events and a lively community spirit to make the Heartlands of Fife unique, appealing and authentically Scottish. Within easy reach of the home of golf at St Andrews, the fishing villages of the East Neuk and Edinburgh, Scotland’s capital city, the Heartlands of Fife has great connections and is an ideal base for a short break or a relaxing holiday. Come and explore our stunning coastline, rolling hills and pretty villages. Surprise yourself with our fascinating wildlife and adrenalin-packed outdoor activities. Relax in our theatres, art galleries and music venues. Also don’t forget to savour our rich natural larder. In the Heartlands of Fife you’ll find a warm welcome and all you could want for a memorable visit that will leave you eager to come back and enjoy more. And you never know, you may even lose your heart! Contents Our Towns & Villages 3 The Great Outdoors 7 Golf Excellence 18 Sporting Fun 19 History & Heritage 21 Culture 24 Innovation & Enlightenment 26 Family Days Out 27 Shopping2 Kirkcaldy & Mid Fife 28 Food & Drink 29 Events & Festivals 30 Travel & Accommodation 32 Visitor Information 33 Discovering Fife 34 welcometofife.com Burntisland Set on a wide, sweeping bay, Burntisland is noted for its Regency terraces and A-listed buildings which can be explored on a Burntisland Heritage Trust guided tour. -

May 2021 Issue No 79

BURGH BUZZ Burntisland’s Free Community Magazine Previous issues at www.burghbuzz.org.uk May 2021 Issue No 79 Burntisland Harbour—Access Prohibited? Burntisland Harbour has seen many changes over the years, but one thing that has remained constant is the freedom for generations of townspeople to wander around it. That freedom is now under serious threat. In February 2020 the harbour’s owner, Forth Ports (FP) met with Anne Smith of Burntisland Community Council to inform her that they intended to install fencing which would render the entire east harbour area and all but the extreme east end of the breakwater out of bounds to all but FP The scenic breakwater will be out of bounds to the general public permitted entrants. The reason given for prohibiting public access was Health and physical and mental health; He also pointed #SaveBurntislandHarbour Facebook group Safety (H&S). out that FP’s parent company/owners - PSP where people can post photos and artworks A full account of this meeting was Investments (in Canada!) - clearly state in to visually celebrate the harbour (over 470 published in the March 2020 minutes of the their literature that, “Environmental, social items posted at the last count), and an Community Council but that was right at and governance (ESG) issues are some of Instagram account to match. the start of Covid and seems to have the most significant drivers of change in As the fencing proposal is so controversial, slipped beneath the public radar. Only the world….” recently did the community become aware we’re lobbying our elected Fife Councillors A pretty convincing appeal. -

February 2021 Issue No 78

BURGH BUZZ Burntisland’s Free Community Magazine Previous issues at www.burghbuzz.org.uk February 2021 Issue No 78 Community Award 2021—Burntisland Emergency Action Team In considering the recipient of the 2021 Essential fundraising and the Burntisland Community Award, rather establishment of support from than focussing on individuals, attention local businesses and traders was directed towards local groups who had resulted in a wide variety of responded to the unprecedented challenges services being made available created by the COVID-19 pandemic. The through the operations of BEAT. quality of nominations was extremely As the pandemic spread, BEAT impressive, all demonstrating services became even more commendable enthusiasm and initiative in essential and the entire set-up their willingness to support their fellow moved to more central premises citizens. on the High Street from where a However, the Burntisland Emergency very efficient support operation Photo: Booth Michael Action Team (BEAT) emerged as the clear continues. In due course, there will be a formal winner of the 41st annual Community BEAT was originally formed by an presentation, with a permanent record of Award. The emergency team was rapidly efficient team comprising Brendan Burns, the overall achievement to be displayed in formed in late March to provide essential Yvonne Crombie and Kirsteen Durkin, the a prominent location. assistance and commodities to the most latter being seconded from Fife Council vulnerable in the community. Overall, it was—and continues to be—an and absolutely essential in establishing outstanding piece of work which has Initially, with the assistance of the local secure databases, the initial recruitment of enabled local people to share the burden of authority and the use of the Toll volunteers and distribution of leaflets. -

A Wee Keek Back – Dunfermline Journal

1 "A WEE KEEK BACK" BY JIM CAMPBELL "CENTRAL AND WEST FIFE LOCAL HISTORY PRESERVATION" ("The Present Preserving the Past for the Future") --------------- 24 St Ronan’s Gardens – Crosshill – KY5 8BL – 01592-860051 [email protected] --------------- At the time of writing this, I have been researching the Central and West Fife Local history for some eight years. During this time I have read quite a few books about Fife written by various and well known authors, most of which I have thoroughly enjoyed and found very enlightening, but I found a source of much greater interest and enlightenment when I began to research the local newspapers. Within the pages of "The Lochgelly Times", the "West Fife Echo" and most importantly "The Dunfermline Journal", I was delighted to find a veritable gold mine of information regarding the development of Central and West Fife. Almost everything of any importance at all in regards to the Central and West Fife area was reported somewhere within the pages of those newspapers, from the early days of coal mining, the beginning and building of the Tay and Forth Railway Bridges, the building and opening of Schools, Co-operative Societies, Gothenburg’s, Miners Welfare Institutes, of the Tramway cars being introduced, the appearance of the Automobile, the Education Act, the introduction of electricity, the opening up of the mining industry in the area, the mining disasters, the Linen trade, the political scene, the birth of towns, burgh's and villages, in short, I believe I discovered for myself the beginning of the Fife that we now know, and thanks to the many different articles consisting of reminiscences, Sanitary Inspectors Reports, Medical Officers reports, etc, that appear in these newspapers, we have been left with a reasonably authentic account of what life was like in Fife in the days gone by. -

Burntisland Community Council, Local Community Groups, Businesses and Interested Local Residents

BURNTISLAND COMMUNITY ACTION PLAN 2016 - 2021 CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 2 OUR COMMUNITY NOW 5 OUR COMMUNITY NOW LIKES 6 OUR COMMUNITY NOW DISLIKES 7 OUR VISION FOR THE FUTURE OF BURNTISLAND 8 MAIN STRATEGIES AND PRIORITIES 11 ACTION 16 MAKING IT HAPPEN BURNTISLAND COMMUNITY ACTION PLAN INTRODUCTION This Community Action Plan summarises community views & information about: • Burntisland – our community now • Our Vision for the future of Burntisland • Main strategies & priorities - the issues that matter most to the community • Our plan for priority projects and actions The plan is our guide for what we - as a community – will try to make happen over the next 5 years. BURNTISLAND COMMUNITY FUTURES STEERING GROUP The preparation of the Community Action Plan has been guided by a local steering group which brings together representatives of the Burntisland Community Council, local community groups, businesses and interested local residents. LOCAL PEOPLE HAVE THEIR SAY The Community Action Plan has been compiled on the basis of the responses gathered through extensive community engagement carried out over a four month period from June – September 2015. The process involved: • a community views survey, delivered to a representative sample of 1,000 households and also available on-line and in community venues • stakeholder interviews and meetings with different groups and individuals representing all aspects of the community • a visitor survey carried out face to face with visitors to Burntisland • preparing a community profile detailing facts 545 COMMUNITY VIEWS SURVEY and figures about the community FORMS WERE RETURNED • a Community Futures Event held on 26 29 STAKEHOLDER MEETINGS WERE HELD September 2015 INVOLVING OVER 70 PEOPLE 229 VISITOR SURVEYS WERE COMPLETED AROUND 320 PEOPLE ATTENDED THE COMMUNITY FUTURES EVENT THANKS TO EVERYONE WHO TOOK PART – IT’S A REALLY GREAT RESPONSE AND GIVES WEIGHT TO THE PRIORITIES IDENTIFIED IN THIS COMMUNITY ACTION PLAN 1 OUR COMMUNITY NOW Street. -

Burntisland Publish.Pub

BURNTISLAND 2015 A SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS ROBERT WILLS UNIVERSITY OF DUNDEE TP51012 20 NOVEMBER 2015 Abstract Burntisland is a coastal town of 6,000 people in South Fife. As it has developed from a fishing village through an important port and export base to its position today as a seaside, commuting and base for marine engineering, the town’s location and topography has influenced its economy, and it economy has influenced its spatial development, identity and sense of place. Recent community planning consultation raised issues including development of the harbour, a desire to improve the High Street, and concern with the scale of recent development. The report looks at these issues through the lens of its historic development and a spatial and qualitative appraisal of the Town today. The historic analysis shows that Burntisland’s harbour has been integral to its development, both as a source of income through fishing and shipbuilding and as a location for railway and ship exports. This has influenced its spatial development through the location of its High Street leading to the harbour, the shape of the port today and the shape of the railway that circuits and cuts through the town. The High Street suffers from traffic issues, a current commuter led lack of quality shopping yet maintains an active café scene,. The economic ups and downs have contributed to the fabric of the town, with a High Street that reveals an eclectic personality, through layers of renovation, and a wider town with areas of grand terraces on the one hand and areas of low grade housing on the other. -

LIBRARY STOCKLIST NOVEMBER 2016 Classmark Author Title, Part No

LIBRARY STOCKLIST NOVEMBER 2016 Classmark Author Title, part no. & title Comment 920AUC Townsend, Annette The Auchmuty family of Scotland and America / Annette Townsend K403435 BOOKCASE FC427 Burness, Lawrence R. A Scottish genealogist's glossary / by Lawrence R. Burness K403088 FC929.2MEL Gilmore, lain A biographical history of the Dysart family of John Melvil & his descendants K403145 FC929.6 Neubecker, Ottfried Heraldry : sources, symbols and meaning / Ottfried Neubecker / with contribu K460928 FH Scottish Association of Family History Societies Bulletin K403696 Outside Shelf FH Dumfries and Galloway Family History Society Newsletter K403697 Outside Shelf FH Fife Family History Society Journal K403698 Outside Shelf FH Tay Valley family historian ; journal of the Tay Valley Family History Socie K403699 Outside Shelf FH Central Scotland Family History Society Newsletter K403700 Outside Shelf FH Sib folk news : newsletter of the Orkney Family History Society K403701 Outside Shelf FH Coontin kin : Shetland Family History Society journal K403702 Outside Shelf FH The Lothians Family History Society newsletter K403703 Outside Shelf FH West Middlesex Family History Society journal K403704 Outside Shelf FH Lanarkshire Family History Society newsletter K403705 Outside Shelf FH Troon @ Ayrshire Family History Society journal K403706 Outside Shelf FH Largs and North Ayrshire Family History Society journal K403707 Outside Shelf FH Newsletter: journal of the Glasgow & West of Scotland Family History Societ K403708 Outside Shelf FH Alloway & Southern -

The Geology of Burntisland

THE GEOLOGY OF BURNTISLAND by Keddie Law Second edition, 2010 At a mere 632 feet (193m) in height, it can hardly claim to be to be amongst Scotland's giant hills, yet the Binn (Hill), visible from almost every point in Burntisland, dominates the town. Some claim that without this wall formed by the Binn and its westerly neighbour Dunearn Hill, the town would suffer more from cold northerly winds. This claim seems to be reflected in the Latin inscription on the town’s coat of arms: “Colles praesidio dedit Deus” - God gives us the protection of the hills. Pictured right - the volcanic vent of the Binn dominates the town. Much of the landscape of the Burntisland area - certainly the hilly parts - owes its shape to the volcanic activity which originated in the volcanic neck represented by the Binn. In terms of age we are looking back at events that occurred some 300 million years or so ago during the Carboniferous Period. The other rocks, less hard in nature, and therefore providing much of the lower ground, are sandstones, shales, thin impure limestones and even a thin seam of coal discovered during the Binnend oil shale industry operations. The presence of several necks - the Binn itself, Kingswood, Kilmundy and Silverbarton - indicates the degree of igneous activity in this area. Map these necks and you will see an arc forming a semi-circle around the town. In Burntisland proper there are several east-west running ridges of higher ground, all composed of either basalt or dolerite and these represent either lava flows or igneous intrusions such as sills. -

Name Relationship Interred Remarks 1872 1873

NAME RELATIONSHIP INTERRED REMARKS page 2 1872 17-May James Stocks 5 (Age 61 widower of Janet Stocks ms Kirkton centre room Farmer leatherer. Long farmer in Broadley north of Kirkcaldy (Death certificate - Scarlett) register of corrected entries - injuries received by his being thrown out of his gig on the Great North Road near Leucharsbeath in the parish of Beath) 24-Jun Mrs Jane Charles 4 wife of A H Charles carpenter at sea Kirkton of A Allan's ground westside of old building (Death cert - age 49 died of (Alexander Henderson Charles 5 Leemount consumption) Burntisland) 26-Jun Thomas Gray 3/6 son of James Gray maltman Grange (age 3) Kirkton north room this boy murdered by his mother by drowning in a tub while out of her senses 03-Aug Elizabeth Hay 4 wife of Robert Robertson, age 33 Kirkton south room died of small pox in Edinburgh, late of Kirkton. (Death cert - Robert a dock labourer. Family staying at 18 Bowling Greeen Street Leith) 08-Aug David Mitchel Kay infant son of Mitchel, Robert Kay labourer Kirkton south room Kay residing in Kirkton (Death cert - age 10 weeks, cause of death want of Kirkton breastmilk) 10 Aug 5 Robert Cunningham 4 1/2 son of William Cunningham (Father was a Kirkton south room this is now the 3rd son of William Cunningham laid below the green road moving o'clock forrester, mother Margaret Cunningham the clouds of the valley (Death Certificate says Robert is age 33 a marine ms Duncan. Wife Margaret Cunningham engineer living at 4 North Fort Street Leith. -

Common Good Asset Register As at 31St March 2021

Commom Good Asset Register as at 31 March 2020 Page 2 Anstruther Page 33 Kirkcaldy Page 3 Auchtermuchty Page36 Ladybank Page 4 Buckhaven Page 37 Leslie Page 5 Burntisland Page 38 Leven Page 10 Cowdenbeath Page 40 Lochgelly Page 11 Crail Page 42 Markinch Page 14 Culross Page 43 Newburgh Page 15 Cupar Page 44 Newport Page 20 Dunfermline Page 46 Pittenween Page 26 Dysart Page 47 Rosyth Page 27 Elie Page 48 St Andrews Page 28 Falkland Page 52 St Monans Page 29 Inverkeithing Page 53 Tayport Page 31 Kinghorn Page 55 Townhill Page 56 Financial information Note: Not all land in a former burgh owned by modern Councils is Common Good. Some of it may have been acquired by other councils, like the former county, or district councils. However, almost all former burghs had a Common Good Fund, which consisted of land, buildings, moveable items like paintings, and cash. The land and buildings which a burgh owned were made up of three main categories: those acquired under a statute (for example, land bought for council housing); land held on trust where a benefactor had provided for a specific trust to be administered by the fund; and Common Good property. What property now forms parts of the Common Good Fund may sometimes need research, as it may not be obvious from the titles what property was acquired for. 2 Anstruther ANSTRUTHER Former Burghs: Kilrenny Royal Burgh, Anstruther Easter Royal Burgh and Anstruther Wester Royal Burgh SRN (GRPN/OR ref) Asset (Name or description) Type of asset Location Town Extent Origin (Provenance) Accession number (if -

Kinghorn, Fife

Earth Science Outdoors Teachers' Guide: Higher & Intermediate 2 Kinghorn, Fife Highlights • Range of volcanic and sedimentary rocks • Contrast between lava flows and an intrusion • Clear examples of faults on a local scale • Raised beach and wave- cut cleft above present sea level The Scottish Earth Science Education Forum (SESEF) is an association of educators and scientists established to promote understanding of planet Earth in Scottish schools and colleges. Membership of SESEF is free – visit www.sesef.org.uk for further information. Scottish Earth Science Education Forum, Grant Institute, School of GeoSciences, University of Edinburgh, West Mains Road, Edinburgh EH9 3JW 0131 651 7048 Teachers' Guide: Higher & Intermediate 2 Kinghorn, Fife 14/10/09 1 Table of Contents Introduction.......................................................................................................................................................2 Using this guide...........................................................................................................................................2 Overview of the geology..............................................................................................................................2 Other features of interest.............................................................................................................................3 Links with the curriculum.............................................................................................................................4 -

Appendix C. Well and Borehole Interpretations and Correlations A.A

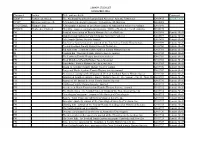

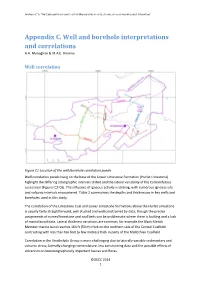

APPENDIX C TO ‘THE CARBONIFEROUS SHALES OF THE MIDLAND VALLEY OF SCOTLAND: GEOLOGY AND RESOURCE ESTIMATION’ Appendix C. Well and borehole interpretations and correlations A.A. Monaghan & M.A.E. Browne Well correlation Figure C1 Location of the well/borehole correlation panels Well correlation panels hung on the base of the Lower Limestone Formation (Hurlet Limestone) highlight the differing stratigraphic intervals drilled and the lateral variability of the Carboniferous succession (Figures C2-C6). The influence of igneous activity is striking, with numerous igneous sills and volcanic intervals encountered. Table 2 summarises the depths and thicknesses in key wells and boreholes used in this study. The correlation of the Limestone Coal and Lower Limestone formations above the Hurlet Limestone is usually fairly straightforward, well studied and well constrained by data, though the precise assignments of named limestone and coal beds can be problematic where there is faulting and a lack of macrofaunal data. Lateral thickness variations are common, for example the Black Metals Member marine band reaches 164 ft (50 m) thick on the northern side of the Central Coalfield contrasting with less than ten feet (a few metres) thick in parts of the Midlothian Coalfield. Correlation in the Strathclyde Group is more challenging due to laterally variable sedimentary and volcanic strata, laterally changing nomenclature, less constraining data and the possible effects of volcanism on biostratigraphically important faunas and floras. ©DECC 2014 1 APPENDIX C TO ‘THE CARBONIFEROUS SHALES OF THE MIDLAND VALLEY OF SCOTLAND: GEOLOGY AND RESOURCE ESTIMATION’ Some of the volcanic strata are fairly well defined spatially by map, borehole/well and geophysical (magnetic) data (e.g.