The Textuality of O Macaco Brasileiro in the Foundation of the Brazilian Journalistic Discourse (1821- 1822) Acta Scientiarum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reading Stephen King: Issues of Censorship, Student Choice, and Popular Literature

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 414 606 CS 216 137 AUTHOR Power, Brenda Miller, Ed.; Wilhelm, Jeffrey D., Ed.; Chandler, Kelly, Ed. TITLE Reading Stephen King: Issues of Censorship, Student Choice, and Popular Literature. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, IL. ISBN ISBN-0-8141-3905-1 PUB DATE 1997-00-00 NOTE 246p. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock No. 39051-0015: $14.95 members, $19.95 nonmembers). PUB TYPE Collected Works - General (020) Opinion Papers (120) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Censorship; Critical Thinking; *Fiction; Literature Appreciation; *Popular Culture; Public Schools; Reader Response; *Reading Material Selection; Reading Programs; Recreational Reading; Secondary Education; *Student Participation IDENTIFIERS *Contemporary Literature; Horror Fiction; *King (Stephen); Literary Canon; Response to Literature; Trade Books ABSTRACT This collection of essays grew out of the "Reading Stephen King Conference" held at the University of Mainin 1996. Stephen King's books have become a lightning rod for the tensions around issues of including "mass market" popular literature in middle and 1.i.gh school English classes and of who chooses what students read. King's fi'tion is among the most popular of "pop" literature, and among the most controversial. These essays spotlight the ways in which King's work intersects with the themes of the literary canon and its construction and maintenance, censorship in public schools, and the need for adolescent readers to be able to choose books in school reading programs. The essays and their authors are: (1) "Reading Stephen King: An Ethnography of an Event" (Brenda Miller Power); (2) "I Want to Be Typhoid Stevie" (Stephen King); (3) "King and Controversy in Classrooms: A Conversation between Teachers and Students" (Kelly Chandler and others); (4) "Of Cornflakes, Hot Dogs, Cabbages, and King" (Jeffrey D. -

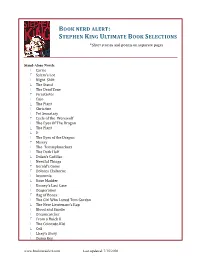

Stephen-King-Book-List

BOOK NERD ALERT: STEPHEN KING ULTIMATE BOOK SELECTIONS *Short stories and poems on separate pages Stand-Alone Novels Carrie Salem’s Lot Night Shift The Stand The Dead Zone Firestarter Cujo The Plant Christine Pet Sematary Cycle of the Werewolf The Eyes Of The Dragon The Plant It The Eyes of the Dragon Misery The Tommyknockers The Dark Half Dolan’s Cadillac Needful Things Gerald’s Game Dolores Claiborne Insomnia Rose Madder Umney’s Last Case Desperation Bag of Bones The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon The New Lieutenant’s Rap Blood and Smoke Dreamcatcher From a Buick 8 The Colorado Kid Cell Lisey’s Story Duma Key www.booknerdalert.com Last updated: 7/15/2020 Just After Sunset The Little Sisters of Eluria Under the Dome Blockade Billy 11/22/63 Joyland The Dark Man Revival Sleeping Beauties w/ Owen King The Outsider Flight or Fright Elevation The Institute Later Written by his penname Richard Bachman: Rage The Long Walk Blaze The Regulators Thinner The Running Man Roadwork Shining Books: The Shining Doctor Sleep Green Mile The Two Dead Girls The Mouse on the Mile Coffey’s Heads The Bad Death of Eduard Delacroix Night Journey Coffey on the Mile The Dark Tower Books The Gunslinger The Drawing of the Three The Waste Lands Wizard and Glass www.booknerdalert.com Last updated: 7/15/2020 Wolves and the Calla Song of Susannah The Dark Tower The Wind Through the Keyhole Talisman Books The Talisman Black House Bill Hodges Trilogy Mr. Mercedes Finders Keepers End of Watch Short -

Stephen King * the Mist

Stephen King * The Mist I. The Coming of the Storm. This is what happened. On the night that the worst heat wave in northern New England history finally broke-the night of July 19-the entire western Maine region was lashed with the most vicious thunderstorms I have ever seen. We lived on Long Lake, and we saw the first of the storms beating its way across the water toward us just before dark. For an hour before, the air had been utterly still. The American flag that my father put up on our boathouse in 1936 lay limp against its pole. Not even its hem fluttered. The heat was like a solid thing, and it seemed as deep as sullen quarry-water. That afternoon the three of us had gone swimming, but the water was no relief unless you went out deep. Neither Steffy nor I wanted to go deep because Billy couldn't. Billy is five. We ate a cold supper at five-thirty, picking listlessly at ham sandwiches and potato salad out on the deck that faces the lake. Nobody seemed to want anything but Pepsi, which was in a steel bucket of ice cubes. After supper Billy went out back to play on his monkey bars for a while. Steff and I sat without talking much, smoking and looking across the sullen flat mirror of the lake to Harrison on the far side. A few powerboats droned back and forth. The evergreens over there looked dusty and beaten. In the west, great purple thunderheads were slowly building up, massing like an army. -

Adventuring with Books: a Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. the NCTE Booklist

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 453 CS 212 097 AUTHOR Jett-Simpson, Mary, Ed. TITLE Adventuring with Books: A Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. Ninth Edition. The NCTE Booklist Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0078-3 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 570p.; Prepared by the Committee on the Elementary School Booklist of the National Council of Teachers of English. For earlier edition, see ED 264 588. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 00783-3020; $12.95 member, $16.50 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC23 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Art; Athletics; Biographies; *Books; *Childress Literature; Elementary Education; Fantasy; Fiction; Nonfiction; Poetry; Preschool Education; *Reading Materials; Recreational Reading; Sciences; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS Historical Fiction; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Intended to provide teachers with a list of recently published books recommended for children, this annotated booklist cites titles of children's trade books selected for their literary and artistic quality. The annotations in the booklist include a critical statement about each book as well as a brief description of the content, and--where appropriate--information about quality and composition of illustrations. Some 1,800 titles are included in this publication; they were selected from approximately 8,000 children's books published in the United States between 1985 and 1989 and are divided into the following categories: (1) books for babies and toddlers, (2) basic concept books, (3) wordless picture books, (4) language and reading, (5) poetry. (6) classics, (7) traditional literature, (8) fantasy,(9) science fiction, (10) contemporary realistic fiction, (11) historical fiction, (12) biography, (13) social studies, (14) science and mathematics, (15) fine arts, (16) crafts and hobbies, (17) sports and games, and (18) holidays. -

China Beyond the Binary

China Beyond the Binary China Beyond the Binary: Race, Gender, and the Use of Story Edited by Kate Rose and Gong Qiangwei China Beyond the Binary: Race, Gender, and the Use of Story Edited by Kate Rose and Gong Qiangwei This book first published 2019 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2019 by Kate Rose, Gong Qiangwei and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-3221-6 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-3221-2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................... vii Chapter One ................................................................................................. 1 “Monkey Mountain and Urban Sprawl: Cycling Where No One Else Wants to Go” Kate Rose Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 25 “Crossing from Luohu to Lo Wu” Miodrag Kojadinović Chapter Three ............................................................................................ 35 “Passing on Traditional Stories in China, South Korea and Scotland” Anna Fancett Chapter Four ............................................................................................. -

An Interview with Stephen King by John C. Tibbetts

“We Walk Your Dog at Night!”: An Interview with Stephen King by John C. Tibbetts Stephen King is a phenomenon. He is without question the most popular writer of horror fiction of all time. In l973 he was living with his family in a trailor in Hampden, Maine, struggling to make a living as a high school teacher, when he published his first novel, Carrie, a tale of a girl with telekinetic powers. Its sales in hardcover were modest (l3,000) but enough to inspire a paperback reprint and a popular film adaption by Brian De Palma in l976. His “breakthrough” book, Salem's Lot, came out that year and quickly sold 3,000,000 copies. Within the next four years The Shining, The Stand, Night Shift, and The Dead Zone—all best-selling horror fiction—established King as the reigning Master of the Macabre. When he co- authored The Talisman in l984 with Peter Straub [See the Straub interview elsewhere in these pages], it was a publishing event unparalleled in modern times. Today over l00 million copies of his books are in print. King's work is frankly derivative of the traditions of l9th century gothic horror. Carrie is written in the style of the "epistolary" novel of the late l8th century. Salem's Lot is an update on Bram Stoker's vampire novel, Dracula. Christine is a variant on Oscar Wilde's The Portrait of Dorian Gray. Pet Sematary is a retelling of W. W. Jacobs' "The Monkey's Paw." And The Dark Half draws from the rich vein of "doppelganger" stories by Poe, Hoffmann, and Stevenson. -

Alma Matters the Class of 1999 Newsletter

Alma Matters The Class of 1999 Newsletter Winter 2004 Class News by Michelle Sweetser South/Midwest Jennifer Moore graduated from Emory Law School in May and started working at a law firm in At- lanta, Georgia (Alston & Bird). She reports that Tully Pruden married Mark Murphy in Mexico in November. Three ’99s were members of the wedding party - Megan Hjermstad, Kate Berkely and Jennifer. Many other ‘99s were in attendance, including Kaitlin Reidy, Michelle Park, Carrie Bourdon, Sommer Pio, Will Leicht, Gus Moore, Jen Holden, Kristen Lucas, and Ali Wiener. The newlyweds now live in San Francisco. Also in Atlanta is James Mykytenko, who is currently a second year general surgery resident at Emory. He will be starting two years of research this summer in the cardiothoracic lab as he is thinking about doing cardiothoracic surgery. James has kept in touch with Matt Delaney and Nat Rink who both live in Somerville, MA, and he saw them most recently in Octo- ber when he also saw Andy Butterworth and Sean Taylor, whom Nat had invited for his birthday. James reports that there are a few other residents at Emory who went to Dartmouth, including Tommy Slaubaugh ’96, who is a fourth year urology resident. James has been doing some activities with the Dartmouth Club of Geor- gia, attending their wine tasting in November and a holi- Muhammad Hutasuhut poses in front of a huge bust day party in December. of Saddam Hussein (adjacent to the palace). Anne Newman is in dental school in San Anto- Muhammad is in Iraq until July, working for the Coa- nio, Texas, and is excited to be in her final year. -

Woodberry Forest School Summer Reading Program 2017 We Hope That All Woodberry Students Are Already Readers, Already Know the Pl

Woodberry Forest School Summer Reading Program 2017 We hope that all Woodberry students are already readers, already know the pleasures of sinking into a great book, and already have a stack of books waiting for this summer. To nudge those of you who haven’t quite made that discovery yet, we are asking you to read three books from the following list over the summer. One of those must be the book selected for an all- school reading assignment by the headmaster, described below. The other two will be your choice from this list we have provided. If you see that a faculty member has recommended a particular book, feel free to ask that faculty member for additional information. In the fall your English teacher will ask you to fill out a pledged questionnaire about your reading. You will receive full credit, partial credit, or no credit depending upon the amount of reading you do. Please understand that summer reading will be figured into your English grade for the fall trimester and that it will have a significant impact on your average. If you read more than the required three books, you will receive extra credit for other books you choose from this list or from a list that you and your English teacher generate (with mutually acceptable titles) before you leave for the summer. Please remember that this program requires reading, not listening to a recorded book instead. Headmaster’s selection for 2017: The Road to Character by David Brooks Your parents and teachers know David Brooks, the noted conservative observer of politics and society, as a New York Times columnist and a commentator on NPR and PBS. -

Book List 5:10:20

Cat Item Description Base Price Fiction 1 GOOD DEED $29.00 Fiction 11 22 63 $19.99 Fiction 18TH ABDUCTION $29.00 Fiction 1984 $9.99 Kids 47 PEOPLE YOULL MEET IN MIDDLE $16.99 Non- 5 PRESIDENTS $18.00 Fiction Non- 50 Psychology Classics $19.95 Fiction Kids 7 HABITS OF HE TEENS $16.99 Fiction 9780143135562 $16.00 Kids A Christmas Carol $6.99 Fiction A Discovery of Witches $18.00 Fiction A Field Guide to the North American $22.00 Fiction A GENTLEMAN IN MOSCOW $17.00 Fiction A Girl Is a Half-formed Thing: A Novel $16.00 Non- A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering $16.95 Fiction Fiction A Man Called Ove $16.00 Fiction A Tree Grows in Brooklyn $16.99 Non- A Very Stable Genius $30.00 Fiction Fiction A Visit From the Goon Squad $16.95 Fiction A Walk to Remember $8.99 Non- A Warning $30.00 Fiction Fiction ALCHEMIST 25/E $16.99 Fiction ALICE NETWORK $16.99 Fiction All the Light We Cannot See $17.00 Fiction AMER MARRIAGE OPRAH BOOK CLUB $26.95 Fiction American Dirt $27.99 Fiction Americanah $16.00 Fiction An Unnecessary Woman, A Novel $16.00 Fiction And Then There Were None $14.98 Fiction Anna Karenina $20.00 1 of 15 Fiction ART OF RACING IN THE RAIN $16.99 Fiction ASYMMETRY $16.00 Kids AURORA RISING $18.99 Non- AUTOBIOG OF MALCOLM X $7.99 Fiction Non- Banished from Johnstown, Racist Bac $23.99 Fiction Fiction Beauchamp Hall $8.99 Non- Becoming: A Guided Journal $19.99 Fiction Fiction BEFORE I GO TO SLEEP $15.99 Fiction Before We Were Yours $17.00 Fiction BEL CANTO $15.99 Fiction BELOVED $16.00 Fiction BIG KAHUNA $28.00 Fiction Big Little Lies $16.00 -

The Parietal Reach Region Codes the Next Planned Movement in a Sequential Reach Task

The Parietal Reach Region Codes the Next Planned Movement in a Sequential Reach Task AARON P. BATISTA1 AND RICHARD A. ANDERSEN2 1Computation and Neural Systems Program and 2Division of Biology, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, California 91125 Received 28 March 2000; accepted in final form 21 September 2000 Batista, Aaron P. and Richard A. Andersen. The parietal reach ments must be planned in series because a particular body part region codes the next planned movement in a sequential reach task. J can only be moved to one location at a time. We trained Neurophysiol 85: 539–544, 2001. Distinct subregions of the posterior monkeys to perform sequential reaches to remembered targets. parietal cortex contribute to planning different movements. The pari- After both targets have been presented and before either reach etal reach region (PRR) is active during the delay period of a memory- has been performed, the monkey must remember both targets, guided reach task but generally not active during a memory-guided saccade task. We explored whether the reach planning activity in PRR and prepare the first reach. Neural signals in PRR might encode is related to remembering targets for reaches or if it is related to both reach targets the monkey is storing in memory. Alterna- specifying the reach that the monkey is about to perform. Monkeys tively, PRR may represent only the target toward which the were required to remember two target locations and then reach to animal is currently planning to reach, consistent with a role for them in sequence. Before the movements were executed, PRR neu- PRR in planning the impending movement. -

Stephen-King-Book-List

BOOK NERD ALERT: STEPHEN KING ULTIMATE BOOK SELECTIONS *Short stories and poems on separate pages Stand-Alone Novels Carrie Salem’s Lot Night Shift The Stand The Dead Zone Firestarter Cujo The Plant Christine Pet Sematary Cycle of the Werewolf The Eyes Of The Dragon The Plant It The Eyes of the Dragon Misery The Tommyknockers The Dark Half Dolan’s Cadillac Needful Things Gerald’s Game Dolores Claiborne Insomnia Rose Madder Umney’s Last Case Desperation Bag of Bones The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon The New Lieutenant’s Rap Blood and Smoke Dreamcatcher From a Buick 8 The Colorado Kid Cell Lisey’s Story Duma Key www.booknerdalert.com Last updated: 7/15/2020 Just After Sunset The Little Sisters of Eluria Under the Dome Blockade Billy 11/22/63 Joyland The Dark Man Revival Sleeping Beauties w/ Owen King The Outsider Flight or Fright Elevation The Institute Later Billy Summers Written by his penname Richard Bachman: Rage The Long Walk Blaze The Regulators Thinner The Running Man Roadwork Shining Books: The Shining Doctor Sleep Green Mile The Two Dead Girls The Mouse on the Mile Coffey’s Heads The Bad Death of Eduard Delacroix Night Journey Coffey on the Mile The Dark Tower Books The Gunslinger The Drawing of the Three The Waste Lands www.booknerdalert.com Last updated: 7/15/2020 Wizard and Glass Wolves and the Calla Song of Susannah The Dark Tower The Wind Through the Keyhole Talisman Books The Talisman Black House Bill Hodges Trilogy Mr. Mercedes Finders Keepers End -

Skeleton-Crew-Stephen-King-Use

This book is for Arthur and Joyce Greene I’m your boogie man that’s what I am and I’m here to do whatever I can ... —K.C. and the Sunshine Band Contents Title Page Dedication Epigraph Introduction The Mist Here There Be Tygers The Monkey Cain Rose Up Mrs. Todd’s Shortcut The Jaunt The Wedding Gig Paranoid: A Chant The Raft Word Processor of the Gods The Man Who Would Not Shake Hands Beachworld The Reaper’s Image Nona For Owen Survivor Type Uncle Otto’s Truck Morning Deliveries (Milkman #1) Big Wheels: A Tale of The Laundry Game (Milkman #2) Gramma The Ballad of the Flexible Bullet The Reach Notes Copyright Page Do you love? Introduction Wait—just a few minutes. I want to talk to you ... and then I am going to kiss you. Wait ... I Here’s some more short stories, if you want them. They span a long period of my life. The oldest, “The Reaper’s Image,” was written when I was eighteen, in the summer before I started college. I thought of the idea, as a matter of fact, when I was out in the back yard of our house in West Durham, Maine, shooting baskets with my brother, and reading it over again made me feel a little sad for those old times. The most recent, “The Ballad of the Flexible Bullet,” was finished in November of 1983. That is a span of seventeen years, and does not count as much, I suppose, if put in comparison with such long and rich careers as those enjoyed by writers as diverse as Graham Greene, Somerset Maugham, Mark Twain, and Eudora Welty, but it is a longer time than Stephen Crane had, and about the same length as the span of H.