Why Menexenus Spells Trouble for Andropov

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Satrap of Western Anatolia and the Greeks

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks Eyal Meyer University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons Recommended Citation Meyer, Eyal, "The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2473. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2473 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2473 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks Abstract This dissertation explores the extent to which Persian policies in the western satrapies originated from the provincial capitals in the Anatolian periphery rather than from the royal centers in the Persian heartland in the fifth ec ntury BC. I begin by establishing that the Persian administrative apparatus was a product of a grand reform initiated by Darius I, which was aimed at producing a more uniform and centralized administrative infrastructure. In the following chapter I show that the provincial administration was embedded with chancellors, scribes, secretaries and military personnel of royal status and that the satrapies were periodically inspected by the Persian King or his loyal agents, which allowed to central authorities to monitory the provinces. In chapter three I delineate the extent of satrapal authority, responsibility and resources, and conclude that the satraps were supplied with considerable resources which enabled to fulfill the duties of their office. After the power dynamic between the Great Persian King and his provincial governors and the nature of the office of satrap has been analyzed, I begin a diachronic scrutiny of Greco-Persian interactions in the fifth century BC. -

Marathon 2,500 Years Edited by Christopher Carey & Michael Edwards

MARATHON 2,500 YEARS EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS BULLETIN OF THE INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SUPPLEMENT 124 DIRECTOR & GENERAL EDITOR: JOHN NORTH DIRECTOR OF PUBLICATIONS: RICHARD SIMPSON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS PROCEEDINGS OF THE MARATHON CONFERENCE 2010 EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 2013 The cover image shows Persian warriors at Ishtar Gate, from before the fourth century BC. Pergamon Museum/Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin. Photo Mohammed Shamma (2003). Used under CC‐BY terms. All rights reserved. This PDF edition published in 2019 First published in print in 2013 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives (CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN: 978-1-905670-81-9 (2019 PDF edition) DOI: 10.14296/1019.9781905670819 ISBN: 978-1-905670-52-9 (2013 paperback edition) ©2013 Institute of Classical Studies, University of London The right of contributors to be identified as the authors of the work published here has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Designed and typeset at the Institute of Classical Studies TABLE OF CONTENTS Introductory note 1 P. J. Rhodes The battle of Marathon and modern scholarship 3 Christopher Pelling Herodotus’ Marathon 23 Peter Krentz Marathon and the development of the exclusive hoplite phalanx 35 Andrej Petrovic The battle of Marathon in pre-Herodotean sources: on Marathon verse-inscriptions (IG I3 503/504; Seg Lvi 430) 45 V. -

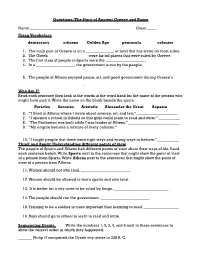

Questions: the Story of Ancient Greece and Rome

Questions: The Story of Ancient Greece and Rome Name ______________________________________________ Class _____ Using Vocabulary democracy citizens Golden Age peninsula colonies 1. The main part of Greece is on a ______________, or land that has water on most sides. 2. The Greek ____________________ were far-off places that were ruled by Greece. 3. The first class of people in Sparta were the ____________________. 4. In a ____________________ the government is run by the people. 5. The people of Athens enjoyed peace, art, and good government during Greece’s ____________________________. Who Am I? Read each sentence then look at the words in the word bank for the name of the person who might have said it. Write the name on the blank beside the quote. Pericles Socrates Aristotle Alexander the Great Aspasia 6. “I lived in Athens where I wrote about science, art, and law.” _____________________ 7. “I opened a school in Athens so that girls could learn to read and write.” ___________ 8. “The Parthenon was built while I was leader of Athens.” __________________________ 9. “My empire became a mixture of many cultures.” _______________________________ 10.“I taught people that there were right ways and wrong ways to behave.” ___________ Think and Apply: Understanding different points of view The people of Sparta and Athens had different points of view about their ways of life. Read each sentence below. Write Sparta next to the sentences that might show the point of view of a person from Sparta. Write Athens next to the sentences that might show the point of view of a person from Athens. -

Feminist Revisionary Histories of Rhetoric: Aspasia's Story

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Supervised Undergraduate Student Research Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects and Creative Work Spring 5-1999 Feminist Revisionary Histories of Rhetoric: Aspasia's Story Amy Suzanne Lawless University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj Recommended Citation Lawless, Amy Suzanne, "Feminist Revisionary Histories of Rhetoric: Aspasia's Story" (1999). Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj/322 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Supervised Undergraduate Student Research and Creative Work at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY HONORS PROGRAM SENIOR PROJECT - APPROVAL N a me: _ dm~ - .l..4ul ~ ___________ ---------------------------- College: ___ M..5...~-~_ Department: ___(gI1~~~ -$!7;.h2j~~ ----- Faculty Mentor: ___lIs ...!_)Au~! _ ..A±~:JJ-------------------------- PROJECT TITLE: - __:fum~tU'it __ .&~\'?lP.0.:-L.!T __W-~~ · SS__ ~T__ Eb:b?L(k.!_ A; ' I -------------- ~~Jl~3-- -2b~1------------------------------ --------------------------------------------. _------------- I have reviewed this completed senior honors thesis with this student and certify that it is a project commensurate with honors -

1 Foreigners As Liberators: Education and Cultural Diversity in Plato's

1 Foreigners as Liberators: Education and Cultural Diversity in Plato’s Menexenus Rebecca LeMoine Assistant Professor of Political Science Florida Atlantic University NOTE: Use of this document is for private research and study only; the document may not be distributed further. The final manuscript has been accepted for publication and will appear in a revised form in The American Political Science Review 111.3 (August 2017). It is available for a FirstView online here: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055417000016 Abstract: Though recent scholarship challenges the traditional interpretation of Plato as anti- democratic, his antipathy to cultural diversity is still generally assumed. The Menexenus appears to offer some of the most striking evidence of Platonic xenophobia, as it features Socrates delivering a mock funeral oration that glorifies Athens’ exclusion of foreigners. Yet when readers play along with Socrates’ exhortation to imagine the oration through the voice of its alleged author Aspasia, Pericles’ foreign mistress, the oration becomes ironic or dissonant. Through this, Plato shows that foreigners can act as gadflies, liberating citizens from the intellectual hubris that occasions democracy’s fall into tyranny. In reminding readers of Socrates’ death, the dialogue warns, however, that fear of education may prevent democratic citizens from appreciating the role of cultural diversity in cultivating the virtue of Socratic wisdom. Keywords: Menexenus; Aspasia; cultural diversity; Socratic wisdom; Platonic irony Acknowledgments: An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 2012 annual meeting of the Association for Political Theory, where it benefitted greatly from Susan Bickford’s insightful commentary. Thanks to Ethan Alexander-Davey, Andreas Avgousti, Richard Avramenko, Brendan Irons, Daniel Kapust, Michelle Schwarze, the APSR editorial team (both present and former), and four anonymous referees for their invaluable feedback on earlier drafts. -

Central Balkans Cradle of Aegean Culture

ANTONIJE SHKOKLJEV SLAVE NIKOLOVSKI - KATIN PREHISTORY CENTRAL BALKANS CRADLE OF AEGEAN CULTURE Prehistory - Central Balkans Cradle of Aegean culture By Antonije Shkokljev Slave Nikolovski – Katin Translated from Macedonian to English and edited By Risto Stefov Prehistory - Central Balkans Cradle of Aegean culture Published by: Risto Stefov Publications [email protected] Toronto, Canada All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system without written consent from the author, except for the inclusion of brief and documented quotations in a review. Copyright 2013 by Antonije Shkokljev, Slave Nikolovski – Katin & Risto Stefov e-book edition 2 Index Index........................................................................................................3 COMMON HISTORY AND FUTURE ..................................................5 I - GEOGRAPHICAL CONFIGURATION OF THE BALKANS.........8 II - ARCHAEOLOGICAL DISCOVERIES .........................................10 III - EPISTEMOLOGY OF THE PANNONIAN ONOMASTICS.......11 IV - DEVELOPMENT OF PALEOGRAPHY IN THE BALKANS....33 V – THRACE ........................................................................................37 VI – PREHISTORIC MACEDONIA....................................................41 VII - THESSALY - PREHISTORIC AEOLIA.....................................62 VIII – EPIRUS – PELASGIAN TESPROTIA......................................69 -

8 Nickolas Pappas and Mark Zelcer What Might Philosophy Say At

��8 Book Reviews Nickolas Pappas and Mark Zelcer Politics and Philosophy in Plato’s Menexenus: Education and Rhetoric, Myth and History (London; New York: Routledge, 2015), vii + 236 pp. $140.00. ISBN 9781844658206 (hbk). What might philosophy say at the burial of citizens who died in war? No sooner is this timely question raised that we must acknowledge that it is far from obvious what the philosopher would say. Civic funerals are moments in political life where the philosopher is confronted by contingency, by a blow to the body politic of which she is part, where she must either speak or keep silent. The confrontation is the subject of Pappas and Zelcer’s book, Politics and Philosophy in Plato’s ‘Menexenus’. The couplings in its subtitle reveal the main ingredients of philosophic speech: Education and Rhetoric, Myth and History. The Menexenus, the authors write, ‘show[s] philosophy bringing a pedagogical impulse to funeral rhetoric that the Republic says philosophical rulers would bring to all aspects of governing a city’ (p. 99). Plato acknowledges the ‘magic of rhetoric’ (p. 136), and the relationship between philosophy and rhetoric is analogous to the relationship between philosophy and politics: in both cases philosophy is the superior partner and the driving force. For Plato, Pappas and Zelcer conclude, the dead are to be ‘buried in philosophy’ (p. 220). Since one cannot assume a ready familiarity with the Menexenus, here is a brief summary. Plato raises Socrates from the dead to converse with the young Menexenus, as the city is poised to commemorate those who died in Athens’ defeat at the end of the Corinthian War in 386 BC. -

The Court of Cyrus the Younger in Anatolia: Some Remarks

STUDIES IN ANCIENT ART AND CIVILIZATION, VOL. 23 (2019) pp. 95-111, https://doi.org/10.12797/SAAC.23.2019.23.05 Michał Podrazik University of Rzeszów THE COURT OF CYRUS THE YOUNGER IN ANATOLIA: SOME REMARKS Abstract: Cyrus the Younger (born in 424/423 BC, died in 401 BC), son of the Great King Darius II (424/423-404 BC) and Queen Parysatis, is well known from his activity in Anatolia. In 408 BC he took power there as a karanos (Old Persian *kārana-, Greek κάρανος), a governor of high rank with extensive military and political competence reporting directly to the Great King. Holding his power in Anatolia, Cyrus had his own court there, in many respects modeled after the Great King’s court. The aim of this article is to show some aspects of functioning and organization of Cyrus the Younger’s court in Anatolia. Keywords: Cyrus the Younger; court; court’s staff and protocol In 4081, Cyrus, commonly known as the Younger (424/423-401), son of the Great King Darius II (424/423-404), was appointed by his father to rule over an important part of the Achaemenid Empire, Anatolia. Cyrus wielded his power there as karanos (Old Persian *kārana-, Greek κάρανος), a high- ranking governor with extensive military and political competence, reporting directly to the Great King (see Podrazik 2018, 69-83; cf. Barkworth 1993, 150-151; Debord 1999, 122-123; Briant 2002, 19, 321, 340, 600, 625-626, 878, 1002; Hyland 2013, 2-5). Cyrus held his own court while in Anatolia. The court was organized along the lines of the King’s court, but was certainly no match for it 1 All dates in the article pertain to the events before the birth of Christ except where otherwise stated. -

Downloadable

EXPERT-LED PETER SOMMER ARCHAEOLOGICAL & CULTURAL TRAVELS TOURS & GULET CRUISES 2021 PB Peter Sommer Travels Peter Sommer Travels 1 WELCOME WHY TRAVEL WITH US? TO PETER SOMMER TR AVELS Writing this in autumn 2020, it is hard to know quite where to begin. I usually review the season just gone, the new tours that we ran, the preparatory recces we made, the new tours we are unveiling for the next year, the feedback we have received and our exciting plans for the future. However, as you well know, this year has been unlike any other in our collective memory. Our exciting plans for 2020 were thrown into disarray, just like many of yours. We were so disappointed that so many of you were unable to travel with us in 2020. Our greatest pleasure is to share the destinations we have grown to love so deeply with you our wonderful guests. I had the pleasure and privilege of speaking with many of you personally during the 2020 season. I was warmed and touched by your support, your understanding, your patience, and your generosity. All of us here at PST are extremely grateful and heartened by your enthusiasm and eagerness to travel with us when it becomes possible. PST is a small, flexible, and dynamic company. We have weathered countless downturns during the many years we have been operating. Elin, my wife, and I have always reinvested in the business with long term goals and are very used to surviving all manner of curve balls, although COVID-19 is certainly the biggest we have yet faced. -

War and Peace in Ancient and Medieval History

War and Peace in Ancient and Medieval History edited by Philip de Souza and John France CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 8RU, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521817035 © Cambridge University Press 2008 This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provision of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published in print format 2008 ISBN-13 978-0-511-38080-8 eBook (Adobe Reader) ISBN-13 978-0-521-81703-5 hardback Cambridge University Press has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of urls for external or third-party internet websites referred to in this publication, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate. Contents List of contributors page vii Acknowledgements ix Note on abbreviations xi 1 Introduction Philip de Souza and John France 1 2 Making and breaking treaties in the Greek world P. J. Rhodes 6 3 War, peace and diplomacy in Graeco-Persian relations from the sixth to the fourth century BC Eduard Rung 28 4 Treaties, allies and the Roman conquest of Italy J. W. Rich 51 5 Parta victoriis pax: Roman emperors as peacemakers Philip de Souza 76 6 Treaty-making in Late Antiquity A. D. -

Illinois Classical Studies

23 Later Euripidean Music ERIC CSAPO In memory of Desmond Conacher, a much-loved teacher, colleague, andfriend. I. The Scholarship In the last two decades of the twentieth century several important general books marked a resurgence of interest in Greek music: Barker 1984 and 1989, Comotti 1989a (an expanded English translation of a work in Italian written in 1979), M. L. West 1992, W. D. Anderson 1994, Neubecker 1994 (second edition of a work of 1977), and Landels 1999. These volumes provide good general guides to the subject, with particular strengths in ancient theory and practice, the history of musical genres, technical innovations, the reconstruction and use of ancient instruments, ancient musical notation, documents, metrics, and reconstructions of ancient scales, modes, and genera. They are too broadly focussed to give much attention to tragedy. Euripidean music receives no more than three pages in any of these works (a little more is usually allocated to specific discussion of the musical fragment of Orestes). Fewer books were devoted to music in drama. Even stretching back another decade, we have: one general book on tragic music, Pintacuda 1978, two books by Scott on "musical design" in Aeschylus (1984) and in Sophocles (1996), and two books devoted to Aristophanes' music, Pintacuda 1982 and L. P. E. Parker 1997. Pintacuda 1978 offers three chapters on basic background, and one chapter for each of the poets. The chapter on Euripides (shared with a fairly standard account of the New Musicians), contains less than four pages of general discussion of Euripides' relationship to the New Music (164-68), which is followed by fifty pages of blow-by-blow description of the musical numbers in each play—a mildly caffeinated catalogue-style already familiar from Webster 1970b: 110-92 and revisited by Scott. -

Women and Property in Ancient Athens: a Discussion of the Private Orations and Menander Cheryl Cox University of Memphis

Women and Property in Ancient Athens: A Discussion of the Private Orations and Menander Cheryl Cox University of Memphis There has been a great deal of discussion in the past two decades or so among social historians and anthropologists of the proposition that women in European societies, both in the past and in the present, have informal power at the private level of the household. Women’s interests were reflected and expressed in succession practices and in the management of the household economy. Central to the status of women was the dowry because of its place in the conjugal household and the negotiations over its use and transmission. A large dowry ensured the woman’s important role in the decisions of the marital household and thus helped to stabilize the marriage. Because the dowry, as the property of the woman’s natal kin, would ideally be transmitted to the man’s children, the man could become involved in the property interests of his wife’s family of origin.1 In a material sense, in classical Athens the wife’s dowry allowed for the cohesion of two households (oikoi): the oikos of her marriage and that of her natal family. The dowry in legal terms belonged to the woman’s natal family, as it had to be returned to her family of origin either on divorce or on the death of her husband and her remarriage. Much of the information we have for dowries pertains to elite families. Because the woman’s dowry could be inherited by the children, it was worth fighting for, especially if she had not received her full share (Dem.