Twelve-Tone Music in America Joseph N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New and Old Tendencies in Labour Mediation Among Early Twentieth-Century US and European Composers

Anna G. Piotrowska New and Old Tendencies in Labour Mediation among Early Twentieth-Century U.S. and European Composers: An Outline of Applied Attitudes1 Abstract: New and Old Tendencies in Labour Mediation among Early Twen- tieth-Century U.S. and European Composers: An Outline of Applied Atti- tudes.This paper presents strategies used by early twentieth-century compos- ers in order to secure an income. In the wake of new economic realities, the Romantic legacy of the musician as creator was confronted by new expecta- tions of his position within society. An analysis of written accounts by com- posers of various origins (British, German, French, Russian or American), including their artistic preferences and family backgrounds, reveals how they often resorted to jobs associated with musicianship such as conducting or teaching. In other cases, they willingly relied on patronage or actively sought new sources of employment offered by the nascent film industry and assorted foundations. Finally, composers also benefited from organized associations and leagues that campaigned for their professional recognition. Key Words: composers, 20th century, employment, vacation, film industry, patronage, foundations Introduction Strategies undertaken by early twentieth-century composers to secure their income were highly determined by their position within society.2 Already around 1900, composers confronted a new reality: the definition of a composer inherited from earlier centuries no longer applied. As will be demonstrated by an analysis of their Anna G. Piotrowska, Institute of Musicology, the Jagiellonian University (Krakow), ul. Westerplatte 10, PL-31-033 Kraków; [email protected] ÖZG 24 | 2013 | 1 131 memoirs, diaries and correspondence, those educated as professional musicians and determined to make their living as active composers had to deal with similar career challenges – regardless of their origins (British, German, French, Russian or Ameri- can), their artistic preferences, or their family backgrounds. -

MSM WIND ENSEMBLE Eugene Migliaro Corporon, Conductor Joseph Mohan (DMA ’21), Piano

MSM WIND ENSEMBLE Eugene Migliaro Corporon, Conductor Joseph Mohan (DMA ’21), piano FRIDAY, JANUARY 18, 2019 | 7:30 PM NEIDORFF-KARPATI HALL FRIDAY, JANUARY 18, 2019 | 7:30 PM NEIDORFF-KARPATI HALL MSM WIND ENSEMBLE Eugene Migliaro Corporon, Conductor Joseph Mohan (DMA ’21), piano PROGRAM JOHN WILLIAMS For New York (b. 1932) (Trans. for band by Paul Lavender) FRANK TICHELI Acadiana (b. 1958) At the Dancehall Meditations on a Cajun Ballad To Lafayette IGOR ST R AVINSKY Concerto for Piano and Wind Instruments (1882–1971) Lento; Allegro Largo Allegro Joseph Mohan (DMA ’21), piano Intermission VITTORIO Symphony No. 3 for Band GIANNINI Allegro energico (1903–1966) Adagio Allegretto Allegro con brio CENTENNIAL NOTE Vittorio Giannini (1903–1966) was an Italian-American composer calls upon the band’s martial associations, with an who joined the Manhattan School of Music faculty in 1944, where he exuberant march somewhat reminiscent of similar taught theory and composition until 1965. Among his students were efforts by Sir William Walton. Along with the sunny John Corigliano, Nicolas Flagello, Ludmila Ulehla, Adolphus Hailstork, disposition and apparent straightforwardness of works Ursula Mamlok, Fredrick Kaufman, David Amram, and John Lewis. like the Second and Third Symphonies, the immediacy MSM founder Janet Daniels Schenck wrote in her memoir, Adventure and durability of their appeal is the result of considerable in Music (1960), that Giannini’s “great ability both as a composer and as subtlety in motivic and harmonic relationships and even a teacher cannot be overestimated. In addition to this, his remarkable in voice leading. personality has made him beloved by all.” In addition to his Symphony No. -

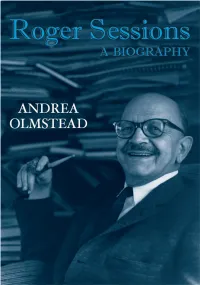

Roger Sessions: a Biography

ROGER SESSIONS: A BIOGRAPHY Recognized as the primary American symphonist of the twentieth century, Roger Sessions (1896–1985) is one of the leading representatives of high modernism. His stature among American composers rivals Charles Ives, Aaron Copland, and Elliott Carter. Influenced by both Stravinsky and Schoenberg, Sessions developed a unique style marked by rich orchestration, long melodic phrases, and dense polyphony. In addition, Sessions was among the most influential teachers of composition in the United States, teaching at Princeton, the University of California at Berkeley, and The Juilliard School. His students included John Harbison, David Diamond, Milton Babbitt, Frederic Rzewski, David Del Tredici, Conlon Nancarrow, Peter Maxwell Davies, George Tson- takis, Ellen Taaffe Zwilich, and many others. Roger Sessions: A Biography brings together considerable previously unpublished arch- ival material, such as letters, lectures, interviews, and articles, to shed light on the life and music of this major American composer. Andrea Olmstead, a teaching colleague of Sessions at Juilliard and the leading scholar on his music, has written a complete bio- graphy charting five touchstone areas through Sessions’s eighty-eight years: music, religion, politics, money, and sexuality. Andrea Olmstead, the author of Juilliard: A History, has published three books on Roger Sessions: Roger Sessions and His Music, Conversations with Roger Sessions, and The Correspondence of Roger Sessions. The author of numerous articles, reviews, program and liner notes, she is also a CD producer. This page intentionally left blank ROGER SESSIONS: A BIOGRAPHY Andrea Olmstead First published 2008 by Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY, 10017, USA Simultaneously published in the UK by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2008 Andrea Olmstead Typeset in Garamond 3 by RefineCatch Limited, Bungay, Suffolk All rights reserved. -

Wallingford Riegger

WALLINGFORD RIEGGER: Romanza — Music for Orchestra Alfredo Antonini conducting the Orchestra of the “Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia-Roma” Dance Rhythms Alfredo Antonini conducting the Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra THIS RELEASE is but further evidence of the growing and gratifying tendency of recent years to recognize Wallingford Riegger as one of the leading and most influential figures in twentieth century American composition, in fact as the dean of American composers. Herbert Elwell, music critic of the Cleveland Plain Dealer, said it in April, 1956: “I am coming more and more to the conclusion that it is Riegger who has been the real leader and pathfinder in contemporary American music . not only a master of his craft but in some ways a prophet and a seer.” In the same month, in Musical America, Robert Sabin wrote: “I firmly believe that his work will outlast that of many an American composer who has enjoyed far greater momentary fame.” Riegger was born in Albany, Georgia, on April 29, 1885. Both his parents were amateur musicians and were determined to encourage their children in musical study. When the family moved to New York in 1900, the young Wallingford was enrolled at the Institute of Musical Art where he studied the cello and composition. Graduating from there in 1907 Riegger then went to Germany to study at the Hochschule für Musik in Berlin with Max Bruch. In 1915-1916 he conducted opera in Würzburg and Königsberg and the following season he led the Blüthner Orchestra in Berlin. Since his return to the United States in 1917, he has been active in many phases of our musical life. -

A Heretic in the Schoenberg Circle: Roberto Gerhard's First Engagement with Twelve-Tone Procedures in Andantino

Twentieth-Century Music 16/3, 557–588 © Cambridge University Press 2019. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. doi: 10.1017/S1478572219000306 A Heretic in the Schoenberg Circle: Roberto Gerhard’s First Engagement with Twelve-Tone Procedures in Andantino DIEGO ALONSO TOMÁS Abstract Shortly before finishing his studies with Arnold Schoenberg, Roberto Gerhard composed Andantino,a short piece in which he used for the first time a compositional technique for the systematic circu- lation of all pitch classes in both the melodic and the harmonic dimensions of the music. He mod- elled this technique on the tri-tetrachordal procedure in Schoenberg’s Prelude from the Suite for Piano, Op. 25 but, unlike his teacher, Gerhard treated the tetrachords as internally unordered pitch-class collections. This decision was possibly encouraged by his exposure from the mid- 1920s onwards to Josef Matthias Hauer’s writings on ‘trope theory’. Although rarely discussed by scholars, Andantino occupies a special place in Gerhard’s creative output for being his first attempt at ‘twelve-tone composition’ and foreshadowing the permutation techniques that would become a distinctive feature of his later serial compositions. This article analyses Andantino within the context of the early history of twelve-tone music and theory. How well I do remember our Berlin days, what a couple we made, you and I; you (at that time) the anti-Schoenberguian [sic], or the very reluctant Schoenberguian, and I, the non-conformist, or the Schoenberguian malgré moi. -

Focus 2020 Pioneering Women Composers of the 20Th Century

Focus 2020 Trailblazers Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century The Juilliard School presents 36th Annual Focus Festival Focus 2020 Trailblazers: Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century Joel Sachs, Director Odaline de la Martinez and Joel Sachs, Co-curators TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction to Focus 2020 3 For the Benefit of Women Composers 4 The 19th-Century Precursors 6 Acknowledgments 7 Program I Friday, January 24, 7:30pm 18 Program II Monday, January 27, 7:30pm 25 Program III Tuesday, January 28 Preconcert Roundtable, 6:30pm; Concert, 7:30pm 34 Program IV Wednesday, January 29, 7:30pm 44 Program V Thursday, January 30, 7:30pm 56 Program VI Friday, January 31, 7:30pm 67 Focus 2020 Staff These performances are supported in part by the Muriel Gluck Production Fund. Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. The taking of photographs and use of recording equipment are not permitted in the auditorium. Introduction to Focus 2020 by Joel Sachs The seed for this year’s Focus Festival was planted in December 2018 at a Juilliard doctoral recital by the Chilean violist Sergio Muñoz Leiva. I was especially struck by the sonata of Rebecca Clarke, an Anglo-American composer of the early 20th century who has been known largely by that one piece, now a staple of the viola repertory. Thinking about the challenges she faced in establishing her credibility as a professional composer, my mind went to a group of women in that period, roughly 1885 to 1930, who struggled to be accepted as professional composers rather than as professional performers writing as a secondary activity or as amateur composers. -

Oefeningen Voor Een Derde Oog

Oefeningen voor een derde oog Dick Hillenius bron Dick Hillenius, Oefeningen voor een derde oog. De Arbeiderspers, Amsterdam 1965 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/hill005oefe01_01/colofon.htm © 2007 dbnl / erven Dick Hillenius 7 ± Chronologisch Dick Hillenius, Oefeningen voor een derde oog 9 [I] RESTJES WEESHUIS Ordesa 20 juli 1963. Toen wij de eerste keer met Tycho op reis wilden - hij was toen 10 maanden - kwamen er alle mogelijke betuttelaars in de weer. L. kwam zelfs met haar psychiater aandragen, vol afgrijzen over het te kwetsen zieleheil en dat het kind er nog jaren later moeilijkheden van zou ondervinden. Op die tientallen die zich vol bezorgdheid keren tegen het meenemen van kinderen op reis, is er nooit één die problemen ziet in het achterlaten bij verzorgers of in een tehuis. Ik weet niet, misschien is dat bij elk kind weer anders, maar wat mij zelf betreft ondervind ik nu, na bijna dertig jaar, de herinnering aan het 4 weken verzorgd achtergelaten zijn in een Hervormd Weeshuis, als een niet verdwenen aantasting. Een week voordat mijn jongste broer werd geboren, op mijn zevende verjaardag, werden mijn andere broer en ik door een tante die werksterdiensten verrichtte in de familie naar het Hervormde Weeshuis gebracht in de Volkerakstraat. Ik herinner me van de eerste dag een man met lange witte baard, de directeur, manden met potten jam, kinderen joelend op de binnenplaats. De kinderen droegen een uniform in de stijl van de tekeningen van Jetses, in de boekjes van Ot en Sien, mode van ±40 jaar tevoren. De meisjes droegen lang haar tot op de schouders (kort was toen mode), de jongens waren kaal met een kuifje van voren. -

Concerts from the Library of Congress 2012-2013

Concerts from the Library of Congress 2012-2013 LIBRARY LATE ACME & yMusic Friday, November 30, 2012 9:30 in the evening sprenger theater Atlas performing arts center The McKim Fund in the Library of Congress was created in 1970 through a bequest of Mrs. W. Duncan McKim, concert violinist, who won international prominence under her maiden name, Leonora Jackson; the fund supports the commissioning and performance of chamber music for violin and piano. Please request ASL and ADA accommodations five days in advance of the concert at 202-707-6362 or [email protected]. Latecomers will be seated at a time determined by the artists for each concert. Children must be at least seven years old for admittance to the concerts. Other events are open to all ages. Please take note: UNAUTHORIZED USE OF PHOTOGRAPHIC AND SOUND RECORDING EQUIPMENT IS STRICTLY PROHIBITED. PATRONS ARE REQUESTED TO TURN OFF THEIR CELLULAR PHONES, ALARM WATCHES, OR OTHER NOISE-MAKING DEVICES THAT WOULD DISRUPT THE PERFORMANCE. Reserved tickets not claimed by five minutes before the beginning of the event will be distributed to stand-by patrons. Please recycle your programs at the conclusion of the concert. THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Atlas Performing Arts Center FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 30, 2012, at 9:30 p.m. THE mckim Fund In the Library of Congress American Contemporary Music Ensemble Rob Moose and Caleb Burhans, violin Nadia Sirota, viola Clarice Jensen, cello Timothy Andres, piano CAROLINE ADELAIDE SHAW Limestone and Felt, for viola and cello DON BYRON Spin, for violin and piano (McKim Fund Commission) JOHN CAGE (1912-1992) String Quartet in Four Parts (1950) Quietly Flowing Along Slowly Rocking Nearly Stationary Quodlibet MICK BARR ACMED, for violin, viola and cello Intermission *Meet the Artists* yMusic Alex Sopp, flutes Hideaki Aomori, clarinets C.J. -

Contact: a Journal for Contemporary Music (1971-1988) Citation

Contact: A Journal for Contemporary Music (1971-1988) http://contactjournal.gold.ac.uk Citation Toplis, Gloria. 1983. ‘Stravinsky’s Pitch Organisation Re-Examined’. Contact, 27. pp. 35-38. ISSN 0308-5066. ! 36 material, each involving different textures, registers, Example 1 harmonies, rhythms, and metres, are set synchro- nically side by side; when considered apart from their immediate context, the blocks may be seen to possess one or another of these parameters in common.' The same author has defined the structur- ing of the first movement of the Symphony in C ( 1938- 40)-one of the neoclassical works most obviously conform to the dictates of functional tonality. The akin in spirit to Classical models-not in terms of the appropriateness of the octatonic theory to Stravin- tonal relationships of sonata form, but in terms of the sky' s output becomes increasingly obvious the more temporal proportion to one another of the sections closely the constitution of the scale itself is examined. (established by means of rather ill-defined tonal For example, each degree articulating a division at areas), which is very much the same as that of a the minor third supports both a minor and a major typical sonata form movement. 3 triad-in Example 1 C supports the triads C-E flat-G Stravinsky students in the sixties were strongly and C-E-G, E flat supports the triads E flat-G flat-B influenced by the somewhat scathing and (in the flat and E flat-G-B flat, and so on; overlapping opinion of later analysts) harmful remarks of Pierre tetrachords a minor third apart contain interlocking Boulez on the composer's compositional technique in minor/major thirds-C-C sharp-D sharp-E, D sharp- works following The Rite of Spring (1911-13). -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 1963-1964

TANGLEWOOD Festival of Contemporary American Music August 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 1964 Sponsored by the Berkshire Music Center In Cooperation with the Fromm Music Foundation RCA Victor R£D SEAL festival of Contemporary American Composers DELLO JOIO: Fantasy and Variations/Ravel: Concerto in G Hollander/Boston Symphony Orchestra/Leinsdorf LM/LSC-2667 COPLAND: El Salon Mexico Grofe-. Grand Canyon Suite Boston Pops/ Fiedler LM-1928 COPLAND: Appalachian Spring The Tender Land Boston Symphony Orchestra/ Copland LM/LSC-240i HOVHANESS: BARBER: Mysterious Mountain Vanessa (Complete Opera) Stravinsky: Le Baiser de la Fee (Divertimento) Steber, Gedda, Elias, Mitropoulos, Chicago Symphony/Reiner Met. Opera Orch. and Chorus LM/LSC-2251 LM/LSC-6i38 FOSS: IMPROVISATION CHAMBER ENSEMBLE Studies in Improvisation Includes: Fantasy & Fugue Music for Clarinet, Percussion and Piano Variations on a Theme in Unison Quintet Encore I, II, III LM/LSC-2558 RCA Victor § © The most trusted name in sound BERKSHIRE MUSIC CENTER ERICH Leinsdorf, Director Aaron Copland, Chairman of the Faculty Richard Burgin, Associate Chairman of the Faculty Harry J. Kraut, Administrator FESTIVAL of CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN MUSIC presented in cooperation with THE FROMM MUSIC FOUNDATION Paul Fromm, President Alexander Schneider, Associate Director DEPARTMENT OF COMPOSITION Aaron Copland, Head Gunther Schuller, Acting Head Arthur Berger and Lukas Foss, Guest Teachers Paul Jacobs, Fromm Instructor in Contemporary Music Stanley Silverman and David Walker, Administrative Assistants The Berkshire Music Center is the center for advanced study in music sponsored by the BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Erich Leinsdorf, Music Director Thomas D. Perry, Jr., Manager BALDWIN PIANO RCA VICTOR RECORDS — 1 PERSPECTIVES OF NEW MUSIC Participants in this year's Festival are invited to subscribe to the American journal devoted to im- portant issues of contemporary music. -

Miriam Gideon's Cantata, the Habitable Earth

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Major Papers Graduate School 2003 Miriam Gideon's cantata, The aH bitable Earth: a conductor's analysis Stella Panayotova Bonilla Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_majorpapers Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Bonilla, Stella Panayotova, "Miriam Gideon's cantata, The aH bitable Earth: a conductor's analysis" (2003). LSU Major Papers. 20. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_majorpapers/20 This Major Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Major Papers by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MIRIAM GIDEON’S CANTATA, THE HABITABLE EARTH: A CONDUCTOR’S ANALYSIS A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Stella Panayotova Bonilla B.M., State Academy of Music, Sofia, Bulgaria, 1991 M.M., Louisiana State University, 1994 August 2003 ©Copyright 2003 Stella Panayotova Bonilla All rights reserved ii DEDICATION To you mom, and to the memory of my beloved father. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Thanks to Dr. Kenneth Fulton for his guidance through the years, his faith in me and his invaluable help in accomplishing this project. Thanks to Dr. Robert Peck for his inspirational insight. Thanks to Dr. Cornelia Yarbrough and Dr. -

American Mavericks Festival

VISIONARIES PIONEERS ICONOCLASTS A LOOK AT 20TH-CENTURY MUSIC IN THE UNITED STATES, FROM THE SAN FRANCISCO SYMPHONY EDITED BY SUSAN KEY AND LARRY ROTHE PUBLISHED IN COOPERATION WITH THE UNIVERSITY OF CaLIFORNIA PRESS The San Francisco Symphony TO PHYLLIS WAttIs— San Francisco, California FRIEND OF THE SAN FRANCISCO SYMPHONY, CHAMPION OF NEW AND UNUSUAL MUSIC, All inquiries about the sales and distribution of this volume should be directed to the University of California Press. BENEFACTOR OF THE AMERICAN MAVERICKS FESTIVAL, FREE SPIRIT, CATALYST, AND MUSE. University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England ©2001 by The San Francisco Symphony ISBN 0-520-23304-2 (cloth) Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file with the Library of Congress. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSI / NISO Z390.48-1992 (R 1997) (Permanence of Paper). Printed in Canada Designed by i4 Design, Sausalito, California Back cover: Detail from score of Earle Brown’s Cross Sections and Color Fields. 10 09 08 07 06 05 04 03 02 01 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 v Contents vii From the Editors When Michael Tilson Thomas announced that he intended to devote three weeks in June 2000 to a survey of some of the 20th century’s most radical American composers, those of us associated with the San Francisco Symphony held our breaths. The Symphony has never apologized for its commitment to new music, but American orchestras have to deal with economic realities. For the San Francisco Symphony, as for its siblings across the country, the guiding principle of programming has always been balance.