62 Question 17

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Estimation of the Relative DNA Content in Species of the Genus Spiraea, Sections Chamaedryon and Glomerati by Flow Cytometry

Ukrainian Journal of Ecology Ukrainian Journal of Ecology, 2019, 9(3), 142-149, doi: 10.15421/2019_74 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Estimation of the relative DNA content in species of the genus Spiraea, sections Chamaedryon and Glomerati by flow cytometry V.A. Kostikova1.2, M.S. Voronkova1, E.Yu. Mitrenina2, A.A. Kuznetsov2, A.S. Erst1,2, T.N. Veklich3, E.V. Shabanova (Kobozeva)1,2 1Central Siberian Botanical Garden, Siberian Branch Russian Academy of Science Zolotodolinskaya St. 101, 630090, Novosibirsk, Russia 2Tomsk State University Lenin Av. 36, 634050, Tomsk, Russia 3Amur Branch of Botanical Garden-Institute of the Far Eastern Branch Russian Academy of Science Ignatievskоe Road, 2 km, 675004, Blagoveshchensk, Russia. E-mail: [email protected] Received: 19.05.2019. Accepted: 26.06.2019 The relative DNA content was studied in seven species of the genus Spiraea L., section Chamaedryon Ser., and in two species, section Glomerati Nakai, from 28 natural populations growing in Asian Russia. The cell nuclei were isolated from a leaf tissue. The relative intensity of fluorescence was measured using flow cytometry of propidium iodide-stained nuclei. The analysis was performed using a CyFlowSpace device (Germany, Sysmex Partec) with a laser radiation source of 532 nm. Fresh leaves of Solanum lycopersicum cv. ‘Stupice’ were used as an internal standard. Data on the relative DNA content are presented for the first time for S. flexuosa Fisch ex Cambess. (0.42–0.47 pg), S. ussuriensis Pojark. (0.49–0.52; 0.85 pg), S. alpina-Pall. (0.49–0.51 pg), S. media Schmidt. (0.45; 0.98–1.01 pg), S. -

Testimonies and Transcripts of World War II Jewish Veterans

http://collections.ushmm.org Contact [email protected] for further information about this collection Testimonies and Transcripts of World War II Jewish Veterans RG-31.061 United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Archives 100 Raoul Wallenberg Place, SW Washington, DC 20024-2126 Tel. (202) 479-9717 Email: [email protected] Descriptive Summary Title: Testimonies and transcripts of World War II Jewish veterans RG Number: RG-31.061 Accession Number: 2007.277 Creator: Instytut ︠iu︡ daı̈ky Extent: 1000 pages of photocopies Repository: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Archives, 100 Raoul Wallenberg Place, SW, Washington, DC 20024-2126 Languages: Russian Administrative Information Access: No restriction on access. Reproduction and Use: Publication by a third party requires a formal approval of the Judaica Institute in Kiev, Ukraine. Publication requires a mandatory citation of the original source. Preferred Citation: [file name/number], [reel number], RG-31.061, Testimonies and transcripts of World War II Jewish veterans, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Archives, Washington, DC. Acquisition Information: Purchased from the Instytut ︠iu︡ daı̈ky (Judaica Institute), Kiev, Ukraine. The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Archives received the photocopied collection via the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum International Archives Program beginning in Sep. 2007. 1 https://collections.ushmm.org http://collections.ushmm.org Contact [email protected] for further information about this collection Custodial History Existence and location of originals: The original records are held by the Instytut ︠iu︡ daı̈ky, Belorusskaya 34-21, Kyiv, Ukraine 04119. Tel. 011 380 44 248 8917. More information about this repository can be found at www.judaica.kiev.ua. Processing History: Aleksandra B. -

Rethinking Rural Politics in Post- Socialist Settings

RETHINKING RURAL POLITICS IN POST- SOCIALIST SETTINGS Natalia Vitalyevna Mamonova 505017-L-bw-Mamanova Processed on: 6-9-2016 This dissertation is part of the project: ‘Land Grabbing in Russia: Large-Scale Inves- tors and Post-Soviet Rural Communities’ funded by the European Research Coun- cil (ERC), grant number 313781. It also benefitted from funding provided by the Netherlands Academie on Land Governance for Equitable and Sustainable Devel- opment (LANDac), the Land Deal Politics Initiative (LDPI), the Political Economy of Resources, Environment and Population (PER) research group of the Interna- tional Institute of Social Studies (ISS). This dissertation is part of the research pro- gramme of CERES, Research School for Resource Studies for Development. © Natalia Vitalyevna Mamonova 2016 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the author. The cover image ‘Land grabbing in former Soviet Eurasia’ (2013) is an original water colour painting by the author, which was initially made for the cover page of the Journal of Peasant Studies Vol. 40, issue 3-4, 2013. ISBN 978-90-6490-064-8 Ipskamp Drukkers BV Auke Vleerstraat 145 7547 PH Enschede Tel.: 053 482 62 62 www.ipskampdrukkers.nl 505017-L-bw-Mamanova Processed on: 6-9-2016 RETHINKING RURAL POLITICS IN POST- SOCIALIST SETTINGS Rural Communities, Land Grabbing and Agrarian Change in Russia and Ukraine HEROVERWEGING VAN PLATTELANDSPOLITIEK IN POSTSOCIALISTISCHE OMGEVINGEN PLATTELANDSGEMEESCHAPPEN, LANDJEPIK EN AGRARISCHE TRANSFORMATIE IN RUSLAND EN OEKRAÏNE Thesis To obtain the degree of Doctor from the Erasmus University Rotterdam by command of the Rector Magnificus Professor Dr. -

Orobanchaceae), a Predominatly Asian Species Newly Found in Albania (SE Europe)

Phytotaxa 137 (1): 1–14 (2013) ISSN 1179-3155 (print edition) www.mapress.com/phytotaxa/ Article PHYTOTAXA Copyright © 2013 Magnolia Press ISSN 1179-3163 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.137.1.1 Phylogenetic position and taxonomy of the enigmatic Orobanche krylowii (Orobanchaceae), a predominatly Asian species newly found in Albania (SE Europe) BOŽO FRAJMAN1, LUIS CARLÓN2, PETR KOSACHEV3, ÓSCAR SÁNCHEZ PEDRAJA4, GERALD M. SCHNEEWEISS5 & PETER SCHÖNSWETTER1 1Institute of Botany, University of Innsbruck, Sternwartestraße 15, A-6020 Innsbruck, Austria; [email protected], [email protected] 2Jardín Botánico Atlántico, Avenida del Jardín Botánico 2230, E-33394 Gijón (Asturias), Spain; [email protected] 3Altai State University, Barnaul, Lenina 61, Russia; [email protected] 4E-39722 Liérganes (Cantabria), Spain; [email protected] 5Department of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany, University of Vienna, Rennweg 14, A-1030 Vienna, Austria; [email protected] Abstract We report on the occurrence of Orobanche krylowii in the Alpet Shqiptare (Prokletije, Albanian Alps) mountain range in northern Albania (Balkan Peninsula). The species was previously known only from eastern-most Europe (Volga-Kama River in Russia), more than 2500 km away, and from adjacent Siberia and Central Asia. We used morphological evidence as well as nuclear ribosomal ITS sequences to show that the Albanian population indeed belongs to O. krylowii and that its closest relative is the European O. lycoctoni, but not O. elatior as assumed in the past. Both Orobanche krylowii and O. lycoctoni parasitize Ranunculaceae (Thalictrum spp. and Aconitum lycoctonum, respectively). We provide an identification key and a taxonomic treatment for O. -

Leninskiy Distr., Moscow Region

City Delivery city Tariffs Delivery time Moscow Ababurovo (Leninskiy distr., Moscow region) 619 1 Moscow Abakan (Khakasiya region) 854 2 Moscow Abaza (Khakasiya region) 1461 6 Moscow Abbakumovo (Moscow region) 619 6 Moscow Abdreevo (Ulyanovsk region) 1351 5 Moscow Abdulovo (Ulyanovsk region) 1351 5 Moscow Abinsk (Krasnodar region) 729 5 Moscow Abramovka (Ulyanovsk region) 1351 5 Moscow Abramtsevo (Balashikhinsky distr., Moscow region) 619 1 Moscow Abrau-Dyurso (Krasnodar region) 729 1 Moscow Achinsk (Krasnoyarsk region) 1461 3 Moscow Achkasovo (Voskresenskiy distr., Moscow region) 619 1 Moscow Adler (Krasnodar region) 729 6 Moscow Adoevshchina (Ulyanovsk region) 1351 5 Moscow Aeroport (Tomsk region) 798 2 Moscow Afipskiy (Krasnodar region) 729 1 Moscow Ageevka (Orel region) 647 1 Moscow Agidel (Bashkiriya region) 1351 3 Moscow Agoy (Krasnodar region) 729 3 Moscow Agrogorodok (Balashikhinsky distr., Moscow region) 619 1 Moscow Agryz (Tatarstan region) 1351 6 Moscow Akademgorodok (Novosibirsk region) 798 1 Moscow Akhmetley (Ulyanovsk region) 1351 5 Moscow Akhtanizovskaya (Krasnodar region) 729 3 Moscow Aksakovo (Mytischi distr., Moscow region) 619 3 Moscow Aksaur (Ulyanovsk region) 1351 5 Moscow Aksay (Rostov-on-Don region) 729 2 Moscow Akshaut (Ulyanovsk region) 1351 5 Moscow Akulovo (Moscow region) 619 1 Moscow Alabushevo (Moscow region) 619 3 Moscow Alakaevka (Ulyanovsk region) 1351 5 Moscow Alapaevsk (Sverdlovskiy region) 1351 5 Moscow Aleksandrov (Vladimir region) 1226 5 Moscow Aleksandrovka (Orel region) 647 1 Moscow Aleksandrovka -

Annual Report Pages of History

WWW.SOGAZ.RU WWW.SOGAZ.RU PAGES OF HISTORY ANNUAL REPORT/07 15 PAGES OF HISTORY WWW.SOGAZ.RU WWW.SOGAZ.RU CONTENTS Annual Report 2007 > CONTENTS . Address by the Chairman of the Board of Directors . 4 Address by the Chairman of the Management Board . 6 “SOGAZ” Insurance Group members . 8 Management Board of OJSC “SOGAZ” . 10 Highlights of the year . .1 Strategy of “SOGAZ” Group up to 2012 . .17 Key results of “SOGAZ” Group operation in 2007 . .21 Social activities of “SOGAZ” Group . .29 Financial report of “SOGAZ” Insurance Group Consolidated balance sheet of “SOGAZ” Insurance Group . 5 Income statement of “SOGAZ” Insurance Group . 9 Auditor’s report on financial statements of OJSC “SOGAZ” . 42 Financial report of OJSC “SOGAZ” . 45 Income statement of OJSC “SOGAZ” . 50 Contact Information . .55 Representative offices of OJSC “SOGAZ” . 56 Representative offices of OJSC “Gazprommedstrakh” . 64 15 PAGES OF HISTORY WWW.SOGAZ.RU “SOGAZ” Insurance Group 15 PAGES OF HISTORY ADDRESS BY THE CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS Annual Report 2007 ADDRESS BY ADDRESS THE CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS The high credit of OJSC “SOGAZ” is confirmed by leading rat- ing agencies, namely, it is rated BB with the prediction “Stable” by Fitch in their international rating for financial stability. I am confident that the development plan of “SOGAZ” Group will be fully met, while its status of a reliable insurer and a trustworthy partner will become even more stable. Chairman of the Management Committee, Dear shareholders, OJSC “Gazprom”, Chairman of the Board of Directors of OJSC “SOGAZ” Aleksey B. -

Phylogenetic Position and Taxonomy of the Enigmatic Orobanche Krylowii (Orobanchaceae), a Predominatly Asian Species Newly Found in Albania (SE Europe)

Phytotaxa 137 (1): 1–14 (2013) ISSN 1179-3155 (print edition) www.mapress.com/phytotaxa/ Article PHYTOTAXA Copyright © 2013 Magnolia Press ISSN 1179-3163 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.137.1.1 Phylogenetic position and taxonomy of the enigmatic Orobanche krylowii (Orobanchaceae), a predominatly Asian species newly found in Albania (SE Europe) BOŽO FRAJMAN1, LUIS CARLÓN2, PETR KOSACHEV3, ÓSCAR SÁNCHEZ PEDRAJA4, GERALD M. SCHNEEWEISS5 & PETER SCHÖNSWETTER1 1Institute of Botany, University of Innsbruck, Sternwartestraße 15, A-6020 Innsbruck, Austria; [email protected], [email protected] 2Jardín Botánico Atlántico, Avenida del Jardín Botánico 2230, E-33394 Gijón (Asturias), Spain; [email protected] 3Altai State University, Barnaul, Lenina 61, Russia; [email protected] 4E-39722 Liérganes (Cantabria), Spain; [email protected] 5Department of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany, University of Vienna, Rennweg 14, A-1030 Vienna, Austria; [email protected] Abstract We report on the occurrence of Orobanche krylowii in the Alpet Shqiptare (Prokletije, Albanian Alps) mountain range in northern Albania (Balkan Peninsula). The species was previously known only from eastern-most Europe (Volga-Kama River in Russia), more than 2500 km away, and from adjacent Siberia and Central Asia. We used morphological evidence as well as nuclear ribosomal ITS sequences to show that the Albanian population indeed belongs to O. krylowii and that its closest relative is the European O. lycoctoni, but not O. elatior as assumed in the past. Both Orobanche krylowii and O. lycoctoni parasitize Ranunculaceae (Thalictrum spp. and Aconitum lycoctonum, respectively). We provide an identification key and a taxonomic treatment for O. -

DHL City of Delivery Tariffs Transit Time Ababurovo

DHL City of delivery Tariffs Transit time Ababurovo (Leninskiy distr., Moscow region) 619 1 Abakan (Khakasiya region) 854 2 Abaza (Khakasiya region) 1461 6 Abbakumovo (Moscow region) 619 6 Abdreevo (Ulyanovsk region) 1351 5 Abdulovo (Ulyanovsk region) 1351 5 Abinsk (Krasnodar region) 729 5 Abramovka (Ulyanovsk region) 1351 5 Abramtsevo (Balashikhinsky distr., Moscow region) 619 1 Abrau-Dyurso (Krasnodar region) 729 1 Achinsk (Krasnoyarsk region) 1461 3 Achkasovo (Voskresenskiy distr., Moscow region) 619 1 Adler (Krasnodar region) 729 6 Adoevshchina (Ulyanovsk region) 1351 5 Aeroport (Tomsk region) 798 2 Afipskiy (Krasnodar region) 729 1 Ageevka (Orel region) 647 1 Agidel (Bashkiriya region) 1351 3 Agoy (Krasnodar region) 729 3 Agrogorodok (Balashikhinsky distr., Moscow region) 619 1 Agryz (Tatarstan region) 1351 6 Akademgorodok (Novosibirsk region) 798 1 Akhmetley (Ulyanovsk region) 1351 5 Akhtanizovskaya (Krasnodar region) 729 3 Aksakovo (Mytischi distr., Moscow region) 619 3 Aksaur (Ulyanovsk region) 1351 5 Aksay (Rostov-on-Don region) 729 2 Akshaut (Ulyanovsk region) 1351 5 Akulovo (Moscow region) 619 1 Alabushevo (Moscow region) 619 3 Alakaevka (Ulyanovsk region) 1351 5 Alapaevsk (Sverdlovskiy region) 1351 5 Aleksandrov (Vladimir region) 1226 5 Aleksandrovka (Orel region) 647 1 Aleksandrovka (Ulyanovsk region) 1351 5 Aleksandrovskiy (Orel region) 647 1 Alekseevka (Belgorod region) 1226 4 Alekseevka (Kinel, Samara region) 1351 1 Alekseevka (Bashkiriya region) 798 4 Aleksin (Tula region) 1226 4 Aleshkino (Ulyanovsk region) 1351 5 Aleksandrovka -

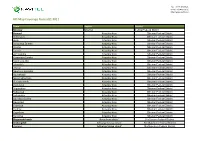

HD Map Coverage Russiaq1 2011

Тел. +7 495 787-66-80 e-mail: [email protected] http://www.navitel.su/ HD Map Coverage RussiaQ1 2011 Town Region District Moscow Moscow Central Federal District Barnaul Altayskiy Kray Siberian Federal District Belmesevo Altayskiy Kray Siberian Federal District Biysk Altayskiy Kray Siberian Federal District Borzovaya Zaimka Altayskiy Kray Siberian Federal District Vlasiha Altayskiy Kray Siberian Federal District Zarinsk Altayskiy Kray Siberian Federal District Zemlyanuha Altayskiy Kray Siberian Federal District Kazennaya Zaimka Altayskiy Kray Siberian Federal District Kamen-na-Obi Altayskiy Kray Siberian Federal District Lebyazh'e Altayskiy Kray Siberian Federal District Lesnoy Altayskiy Kray Siberian Federal District Nauchniy Gorodok Altayskiy Kray Siberian Federal District Novoaltajsk Altayskiy Kray Siberian Federal District Novomykhailivka Altayskiy Kray Siberian Federal District Plodopitomnik Altayskiy Kray Siberian Federal District Polzunovo Altayskiy Kray Siberian Federal District Prigorodniy Altayskiy Kray Siberian Federal District Rubtsovsk Altayskiy Kray Siberian Federal District Sadovodov Altayskiy Kray Siberian Federal District Sibirskaya Dolina Altayskiy Kray Siberian Federal District Slavgorod Altayskiy Kray Siberian Federal District Chernitsk Altayskiy Kray Siberian Federal District Yuzhniy Altayskiy Kray Siberian Federal District Yagodnoe Altayskiy Kray Siberian Federal District Yarovoye Altayskiy Kray Siberian Federal District Blagoveshchensk Amurskaya oblast' Far Eastern Federal District Archangelsk Arkhangel'skaya oblast' -

R U S S Ia N F O Re S Try R E V Ie W № 4 W W W .Le S P Ro M in Fo Rm .C

ISSN 1995-7343 ISSN Russian Forestry Review № 4 www.LesPromInform.com Russian Forestry Review CONTENTS #4 (2011) Specialized information-analytical magazine ISSN 1995-7343 THE RUSSIAN («Российское лесное обозрение») специализированный FORESTRY COMPLEX: информационно-аналитический журнал на английском языке Периодичность: 1 раз в год Издатель: ООО «ЭКОЛАЙФ» A GENERAL OVERVIEW Адрес редакции: Россия, 196084, Санкт-Петербург, 8 Лиговский пр., 270, офис 17 EDITORIAL TEAM: General Director Svetlana YAROVAYA [email protected] Editor-in-Chief, Business Development Director INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................... 6 Oleg PRUDniKOV [email protected] A COMPLEX VIEW International Marketing Director The Russian Forestry Complex: a General Overview .................................. 8 Elena SHUMeyKO [email protected] The Growing Russian Forestry Industry Art-Director Will Receive Better Equipment and Service............................................12 Andrei ZABELin [email protected] Designers RUSSIA’S TIMBER INDUSTRY Anastasiya PAVLOVA & Alexander UsTenKO PR and Distribution EMBARKS ON A CIVILIZED Elena SHUMeyKO [email protected] COURSE OF DEVELOPMENT 24 Proofreaders Simon PATTERSON & Shura COLLinsON INVESTMENTS CONTACTS Russia 's Fading Competitive Edge ........................................................14 Russia St.Petersburg, 196084 Meeting the Challenge of Harsh Harvesting Conditions ...........................22 Ligovsky Ave., 270, office 17 Tel./fax: