Educating Educators of Memory: Reflections on an Insite Teaching Programme

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gratuities Gratuities Are Not Included in Your Tour Price and Are at Your Own Discretion

Upon arrival into Budapest, you will be met and privately transferred to your hotel in central Budapest. On the way to the hotel, you will pass by sights of historical significance, including St. Stephen’s Basilica, a cross between Neo-Classical and Renaissance-style architecture completed in the late 19th century and one of Budapest’s noteworthy landmarks. Over the centuries, Budapest flourished as a crossroads where East meets West in the heart of Europe. Ancient cultures, such as the Magyars, the Mongols, and the Turks, have all left an indelible mark on this magical city. Buda and Pest, separated by the Danube River, are characterized by an assortment of monuments, elegant streets, wine taverns, coffee houses, and Turkish baths. Arrival Transfer Four Seasons Gresham Palace This morning, after meeting your driver and guide in the hotel lobby, drive along the Danube to see the imposing hills of Buda and catch a glimpse of the Budapest Royal Palace. If you like, today you can stop at the moving memorial of the Shoes on the Danube Promenade. Located near the parliament, this memorial honors the Jews who fell victim to the fascist militiamen during WWII. Then drive across the lovely 19th-century Chain Bridge to the Budapest Funicular (vertical rail car), which will take you up the side of Buda’s historic Royal Palace, the former Hapsburg palace during the 19th century and rebuilt in the Neo-Classical style after it was destroyed during World War II. Today the castle holds the Hungarian National Gallery, featuring the best of Hungarian art. -

H.U.G.E.S. a Visit to Budapest (25Th September -30Th September

H.U.G.E.S. A Visit to Budapest (25th September -30th September) 26th September, Monday The first encounter between our students and the Comenius partners took place in the hotel lobby, from where they were escorted by two volunteer students (early birds) to school. On the way to school they were given a taste of the city by the same two students, Réka Mándoki and Eszter Lévai, who introduced some of the famous buildings and let the enthusiastic teachers take several photos of them. In the morning there was a reception in school. The teachers met the head mistress, Ms Veronika Hámori, and the deputy head, Ms Katalin Szabó, who showed them around in the school building. Then, the teachers visited two classroom lessons, one of them being an English lesson where they enchanted our students with their introductory presentations describing the country they come from. The second lesson was an advanced Chemistry class, in which our guests were involved in carrying out experiments. Although they blew and blew, they didn’t blow up the school building. In the afternoon, together with the students involved in the project (8.d), we went on a sightseeing tour organised by the students themselves. A report on the event by a pupil, Viktória Bíró 8.d At the end of September my English group took a trip to the heart of Budapest. We were there with teachers from different countries in Europe. We walked along Danube Promenade, crossed Chain Bridge and went up to Fishermen’s Bastion. Fortunately, the weather was sunny and warm. -

Regional Types of Tourism in Hungary

István Tózsa – Anita Zátori (eds.) Department of Economic Geography and Futures Studies, Corvinus University of Budapest Metropolitan Tourism Experience Development Selected studies from the Tourism Network Workshop of the Regional Studies Association, held in Budapest, Hungary, 2015 Edited by István Tózsa and Anita Zátori Read by Catherine R. Feuerverger Cover by László Jeney ISBN: 978-963-503-597-7 Published by the Department of Economic Geography and Futures Study 2015 1 2 Introduction On January 28-30, 2015 Corvinus University of Budapest hosted the latest workshop of the Regional Studies Association’s Tourism Research Network. The event had been held previously in Izmir, Aalborg, Warsaw, Östersund, Antalya, Leeds and Vila-seca Catalonia. The aim of the RSA research network is to examine tourism diversity from the perspective of regional development in order to identify current challenges and opportunities in a systematic manner, and hence provide the basis for a more well-informed integration of tourism in regional development strategies and move beyond political short-termism and buzzword fascination. In the frame of the network a series of workshops have been organised from various topics of destination management till rural tourism. In the age of budget airlines and increased mobility, the importance for metropolitan areas of positioning themselves in an increasingly competitive environment where the boundaries between international tourism and local leisure are becoming blurred, has increased. Metropolitan areas are highly preferred targets for tourists owing to their diversified and concentrated attractions particularly cultural heritages and up-to-date events as well as to their business environment. They are the focal points of tourism in a lot of regions and countries. -

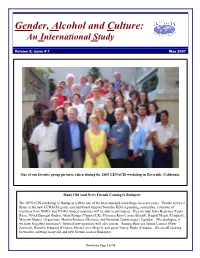

May 2007, Vol. 5, Issue 1

Gender, Alcohol and Culture: An International Study Volume 5, Issue # 1 May 2007 One of our favorite group pictures, taken during the 2005 GENACIS workshop in Riverside, California. Many Old (and New) Friends Coming to Budapest The GENACIS workshop in Budapest will be one of the best-attended workshops in recent years. Thanks to travel funds in the new GENACIS grant, and additional support from the KBS organizing committee, a number of members from WHO- and PAHO-funded countries will be able to participate. They include Julio Bejarano (Costa Rica), Vivek Benegal (India), Akan Ibanga (Nigeria/UK), Florence Kerr-Correa (Brazil), Raquel Magri (Uruguay), Myriam Munné (Argentina), Martha Romero (Mexico), and Nazarius Tumwesigye (Uganda). (We apologize if we have forgotten someone!) Several new members will also join us. Among them are Jennie Connor (New Zealand), Danielle Edouard (France), Maria Lima (Brazil) , and guest Nancy Poole (Canada). We are all looking forward to meeting many old and new friends soon in Budapest. Newsletter Page 1 of 10 Some Highlights of 2007 GENACIS Workshop The GENACIS workshop in Budapest will include several new features. One is a series of overview presentations that will summarize major findings to date in the various GENACIS components. The overviews will be presented by Kim Bloomfield (EU countries), Isidore Obot (WHO-funded countries), Maristela Monteiro (PAHO-funded countries), and Sharon Wilsnack (other countries). Robin Room will provide a synthesis of findings from the various components. On Saturday afternoon, Moira Plant will facilitate a discussion of “GENACIS history and process.” GENACIS has faced a number of challenges and Members of the GENACIS Steering Committee at generated many creative solutions in its 15-year their December 2006 meeting in Berlin. -

Post-Riverboat Vacation Stretchers May/June 2022

Budapest POST-RIVERBOAT VACATION STRETCHERS MAY/JUNE 2022 USA & CANADA: 800-631-6277 x1 | INTERNATIONAL: 415-962-5700 x1 Budapest Consistently rated as the Best European Destination, Hungary’s capital, Budapest, is bisected by the River Danube. Its 19th-century Chain Bridge connects the hilly Buda district with flat Pest. A funicular runs up Castle Hill to Buda’s Old Town, where the Budapest History Museum traces city life from Roman times onward. The central area of Budapest along the Danube River is classified as a UNESCO World Heritage Site and has several notable monuments, including the Hungarian Parliament and the Buda Castle. The city also has around 80 geothermal springs, the largest thermal water cave system, second largest synagogue, and third largest Parliament building in the world. All of this creates the dramatic skyline Budapest is known for making it one of the most photographed cities in Europe. A visit to Budapest would not be complete without visiting the Central Market Hall! Known for paprika, you’ll also find beautiful fruits, vegetables and meats as well as laces, leather, porcelain, clothing and a food court to experience a lángos, a deep-fried delight that can be prepared sweet or savory. With so much history and culture to experience, extending your stay in Budapest with Olivia is an opportunity you won’t want to miss! 1-NIGHT BUDAPEST VACATION STRETCHER (MAY 31–JUNE 1, 2022) $399 PP DOUBLE OCCUPANCY— SUPERIOR RIVER VIEW ROOM $559 PP SINGLE OCCUPANCY— SUPERIOR RIVER VIEW ROOM INCLUDED • 1-night stay at InterContinental -

5-Day Budapest City Guide a Preplanned Step-By-Step Time Line and City Guide for Budapest

5 days 5-day Budapest City Guide A preplanned step-by-step time line and city guide for Budapest. Follow it and get the best of the city. 5-day Budapest City Guide 2 © PromptGuides.com 5-day Budapest City Guide Overview of Day 1 LEAVE HOTEL Tested and recommended hotels in Budapest > Take Metro Line 2 (Red) to Batthyány tér station 09:00-09:20 Batthyány Square The best view of the Page 5 Hungarian Parliament Take Metro Line 2 (Red) from Batthyány tér station to Kossuth tér station (Direction: Örs Vezér tere) - 10’ 09:30-10:00 Kossuth Square Historic square Page 5 Take a walk to Hungarian Parliament 10:00-11:00 Hungarian Parliament One of the most Page 6 imposing parliament Take a walk to the House of Hungarian Art Nouveau - buildings in the world 10’ 11:10-11:55 House of Hungarian Art Nouveau Hidden treasure of Art Page 6 Nouveau architecture Take a walk to Szabadság Square - 5’ 12:00-12:30 Szabadság Square Grand and spacious Page 7 square Take a walk to St. Stephen’s Basilica - 15’ 12:45-13:55 St. Stephen's Basilica Imposing Page 8 neo-Renaissance Lunch time church Take a walk to Váci Street 15:30-16:40 Váci Street Budapest's most Page 8 upscale shopping street Take a walk to Danube Promenade - 10’ 16:50-17:35 Danube Promenade Stunning view over the Page 9 Danube and Buda side END OF DAY 1 of the city © PromptGuides.com 3 5-day Budapest City Guide Overview of Day 1 4 © PromptGuides.com 5-day Budapest City Guide Attraction Details 09:00-09:20 Batthyány Square (Batthyány tér, Budapest) THINGS YOU NEED TO KNOW The historic Main Street (Fő utca) also Batthyány Square is a charming town crosses the square square directly opposite of Parlament on Another monument commemorates Ferenc Buda side. -

BUDAPEST 2017 10Th - 16Th September 2017

Walton-on-the-Hill DFAS BUDAPEST 2017 10th - 16th September 2017 £899 per person* Discover a city steeped in history and culture on the banks of OUR TOUR 7 DAYS - 6 NIGHTS the River Danube. Eclectic Budapest is blessed with an array of What’s included • Return flights from London to Budapest beautiful architecture with many baroque, neoclassical and art • Executive coach for airport transfers & daily excursions nouveau buildings and an abundance of museums and galleries. • English speaking guide & admissions as per itinerary overleaf Our tour will incorporate a selection of the highlights, but we • 6 nights bed & breakfast accommodation in deluxe bedrooms will also allow some time for individual exploration. • Dinner on the night of arrival at the hotel • Danube dinner cruise • Lunch on the last day Our hotel • Gratuities for coach drivers and guides Located in the heart of Budapest, the • Whisper sets (when needed) 4 star Astoria Hotel combines timeless What’s not included elegance with all the amenities you would • Single supplement of £144 for the duration of the tour (twin/double for expect of a recently renovated modern sole use) hotel. The Mirror Café and Restaurant • Travel insurance - £38 per person. The serve tasty cuisine popular with visitors policy has an upper age limit of 85 and locals alike. All air-conditioned guest years as at the date of return bedrooms have en-suite facilities and are • Items of a personal nature such as drinks, souvenirs, etc. equipped with telephone, satellite TV, safe • Meals other than those specified and internet access. *Based on a minimum of 40 members travelling. -

Shoes on the Danube Promenade Schuhe Am Donauufer

1/20 Shoes on the Danube Promenade Schuhe am Donauufer 2/20 Memorial in Budapest documents, witnesses, letters about 8. January 1945 154 rescued persons Ebook Tamas Szabo 2012 Munich Contact: [email protected] 3/20 Acknowledgments A statement of gratitude for assistance in producing this work. To all the outstanding people who have motivated me through e-mail, phone, interviews I owe an everlasting debt of thanks to: Dr. Erwin K. Koranyi professor emeritus at the University Ottawa witness in his Book „Chronicle of a Life”, 2006 Tibor Farkas, Melbourne, journalist, research about Pal Szalai Jacov Steiner professor emeritus at the Hebrew University Jerusalem witness in letters to Yad Vashem Dr. Eva Löw and her sister Dr. Anna Klaber in Basel, witness Maria Ember, journalist and researcher in Budapest, interviews in newsletter and her book 1990, 1992 Gabor Forgacs, Budapest, witness, archives, list of persons in Wallenbergs central office Dr. George Kende, journalist in Jerusalem, witness in newspapers in Jerusalem, letters to Yad Vashem Professor Szabolcs Szita director Holocaust Museum in Budapest, letters and interviews in Jerusalem, Yad Vashem Professor Laszlo Karsai University Szeged, Hungary, letters and interviews in Jerusalem, Yad Vashem Fabienne Regard Docteur en science politique, historienne, Expert au Conseil de l’Europe Strasbourg Dr. Jozsef Korn lawyer in Budapest, thanks for contacts Wallenberg Family Archives, Marie Dupuy (Marie von Dardel) niece of Raoul Wallenberg, documnets from the years 1940 - 1948 and internet sources Professor Tibor Vamos, former director from „The Computer and Automation Research Institute, Hungarian Academy of Sciences", my employer in the years 2004 – 2006. -

Entering Budapest, Hungary on the Danube River. Margaret Bridge in View

VIKING TRAVELOG GRAND EUROPEAN RIVER CRUISE RHINE-MAIN-DANUBE RIVERS DAY 14 – BUDAPEST Entering Budapest, Hungary on the Danube River. Margaret Bridge in view. HUNGARY’S GRACEFUL AND INSPIRING CAPITAL Take in one of Europe’s great cultural capitals. Over the last few decades, Budapest has reemerged as one of the continent’s iconic cities, divided by the lilting Danube and connected by the graceful Chain Bridge. Meet your guide for a panoramic tour, beginning in modern Pest. Along the elegant Andrássy Avenue, the Champs-Élysées of Budapest, admire the Hungarian State Opera House. Stop at Heroes’ Square, a wide-open plaza of monuments and statues commemorating the Magyar state. Across the river, explore the more traditional Buda side of the city. Here you will visit the Castle District with its massive hilltop castle complex, the turreted Fishermen’s Bastion and Matthias Church, named for the country’s most popular medieval king. From the heights of Buda Hill, enjoy fantastic views of the famous Chain Bridge, the first span to ever connect the two halves of the city when it opened in 1849. 1 Ancient Viking longship (galley prow with oars) sculpture (winged figurehead) at the Margaret Bridge. http://www.aviewoncities.com/budapest/margaretbridge.htm [Note: This vivid image came to mind at the end of the day when an accident occurred near here. I write about it in my epilogue.] First sighting of the majestic Parliament building on the Pest side of Buda-Pest. 2 The Buda side of Buda-Pest. The Castle complex could be seen on the hill. -

2010-06 Information on Budapest

GENERAL INFORMATION ABOUT HUNGARY AND BUDAPEST FOR THE PARTICIPANTS OF GBE ANNUAL CONFERENCE 2010 THURSDAY , JULY 8TH – FRIDAY , JULY 9TH 2010 General Information on Hungary Capital : Budapest Language : Hungarian Country Code : +36 Area : 93,000 sq km Currency : Hungarian forint Electricity : 220V, 50Hz Population : 10.4 million Time : GMT +1 hour Some interesting webpages: Here you can find brochures, videos and interesting facts about tourism in Hungary: http://www.hungarytourism.hu/ A fun magazine about Hungarians and Hungary through a foreigner’s eyes: http://www.hunreal.com/ Transportation The Airport is located within the boundaries of Budapest, 16km eastward from the City, alongside Main Road 4. By train Passengers can easily reach Ferihegy Terminal 1 from the Western Railway Station in Budapest. On the weekdays 51 and at weekends 38 trains ease the traffic from the city centre to the airport in less than half an hour for 365 HUF. There are around 60 trains on weekdays and 45 at weekends from the airport to the city center. More » Budapest nyugati pályaudvar ( Budapest Western Railway Station) The square serves as a transportation hub with several bus lines, trams 4 and 6, and a station of the Budapest Metro (M3 line). A characteristic vehicle of the Grand Boulevard is the tram, No. 4 and 6, reaching Buda both in the north ( Moszkva tér ) and the south ( Móricz Zsigmond körtér ). 1/6 By taxi A new taxi operator has recently started operating from Ferihegy. Zóna taxi offers low prices and high quality levels of service. At the same time, pre-ordered taxis can be ordered as usual at the airport. -

72 Hour Guide Budapest

Wombat’s is in the absolute center of the city. If you go hesitate in trying one of the bars or shops for a sandwich. After seeing a large outside from the lobby and go down Király street to the Be careful with prices, and reserve yourself for dinner time! amount of 19th century right, you arrive at Deák Ferenc square—the heart of buildings, and many Budapest. From there, you can reach most sights by foot, On the other side of the embassies, we will arrive bus, tram or metro (subway) to get to the places listed district are the Fisherman’s in front of the Heroes below. Bastion, and Mattias Square. There you will Church. The latter, is one of see: a representation of the However, we advise you that you the oldest churches in seven tribes who formed Hungary, as well as the most cross the square, and walk towards Hungary. important kings, and politicians of Hungarian history. Vörösmarty square which offers a very nice Christmas fair during If you would like to visit the labyrinth cave, then find Uri The museum of fine art is on the left, and the art gallery is winter months. You can enjoy street. Follow the road that goes to Buda, and take the stairs on the right. Both hold some important expositions. So, chimney cake and roasted chestnuts, while sipping some between this street and The Royal Palace. please ask our receptionist before you leave the hostel if mulled wine. During summertime, it offers craft fairs and you want to know more information. -

Reconsidered Paradigm Change in Holocaust Memorialisation. Heinrich Böll Stiftung Andrea Petö

”Bitter experiences” reconsidered paradigm change in Holocaust memorialisation. Heinrich Böll Stiftung Andrea Petö To cite this version: Andrea Petö. ”Bitter experiences” reconsidered paradigm change in Holocaust memorialisation. Hein- rich Böll Stiftung. 2019. hal-03232931 HAL Id: hal-03232931 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03232931 Submitted on 25 May 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 7/2/2019 “Bitter experiences” reconsidered: paradigm change in Holocaust memorialisation | Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung “Bitter experiences” reconsidered: paradigm change in Holocaust memorialisation Analysis The Holocaust narrative elevated the moral command of “Never Again” into a measure of universal integrity. But now a major paradigm change is happening in Holocaust memorialisation that will have a major impact on European identity. 28. June 2019 by Andrea Pető The Shoes on the Danube Promenade is a memorial that honors the Jews who were killed by fascist Arrow Cross militiamen in Budapest during World War II — Image Credits “Europe reunited after bitter experiences” is how the Preamble of the European Constitutional Treaty (2004) begins. One can legitimately ask which experiences were those “bitter” ones? The term “bitter experiences” in the Preamble euphemistically refers to the events of the Second World War and the Holocaust, but recently this unfortunate generalisation has led to major consequences.