Prendini.2010.Cladistics.Troglo.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adec Preview Generated PDF File

Records ofthc Western Australian Museum Supplement No. 52: 191-198 (1995). A new ischnurid scorpion from the Northern Territory, Australia N.A. Locket Department of Anatomy and Histology, University of Adelaide, South Australia 5005, Australia Abstract -A new species of ischnurid scorpion is described. Liocheles longimantls has been collected in Oenpelli Caves and in Kakadu National Park, Northern Territory. The scorpion, found near the mouth of the cave and under a log in Kakadu, appears normally pigmented and has apparently normal eyes. The new species is compared with other Liocheles from Australia; a striking difference from these is the much elongated pedipalps. INTRODUCTION with absent or reduced eyes, indications of the Scorpions are well known to inhabit caves and troglobitic habit. Eleven of these are from Mexico, some show marked adaptations to this habitat. The with one each from Ecuador and Sarawak; the earliest record of a cave scorpion is that of latter, Chaerilus chapmani (Vachon and Louren<;:o Belisarius xambeui, described from Conat and the 1985) is the only non-American species. valley of Queillan, eastern Pyrenees, by Simon Exploration of the Australian cave fauna has (1879), who recorded it from under stones, making included work on spiders by Main (1969, 1976), no mention of caves. This species occurs within Gray (1973a,b) and Main and Gray (1985). and outside caves (Auber 1959), particularly in the Humphreys (1991) and colleagues have studied the interstices between blocks of limestone beneath a fauna of caves in north-western Australia, to which covering of leaves and moss. Though Simon stated he has led expeditions. -

Reprint Covers

TEXAS MEMORIAL MUSEUM Speleological Monographs, Number 7 Studies on the CAVE AND ENDOGEAN FAUNA of North America Part V Edited by James C. Cokendolpher and James R. Reddell TEXAS MEMORIAL MUSEUM SPELEOLOGICAL MONOGRAPHS, NUMBER 7 STUDIES ON THE CAVE AND ENDOGEAN FAUNA OF NORTH AMERICA, PART V Edited by James C. Cokendolpher Invertebrate Zoology, Natural Science Research Laboratory Museum of Texas Tech University, 3301 4th Street Lubbock, Texas 79409 U.S.A. Email: [email protected] and James R. Reddell Texas Natural Science Center The University of Texas at Austin, PRC 176, 10100 Burnet Austin, Texas 78758 U.S.A. Email: [email protected] March 2009 TEXAS MEMORIAL MUSEUM and the TEXAS NATURAL SCIENCE CENTER THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT AUSTIN, AUSTIN, TEXAS 78705 Copyright 2009 by the Texas Natural Science Center The University of Texas at Austin All rights rereserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, including electronic storage and retrival systems, except by explict, prior written permission of the publisher Printed in the United States of America Cover, The first troglobitic weevil in North America, Lymantes Illustration by Nadine Dupérré Layout and design by James C. Cokendolpher Printed by the Texas Natural Science Center, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas PREFACE This is the fifth volume in a series devoted to the cavernicole and endogean fauna of the Americas. Previous volumes have been limited to North and Central America. Most of the species described herein are from Texas and Mexico, but one new troglophilic spider is from Colorado (U.S.A.) and a remarkable new eyeless endogean scorpion is described from Colombia, South America. -

Download the Full Paper

Int. J. Biosci. 2021 International Journal of Biosciences | IJB | ISSN: 2220-6655 (Print), 2222-5234 (Online) http://www.innspub.net Vol. 18, No. 2, p. 146-162, 2021 RESEARCH PAPER OPEN ACCESS Scorpion’s Biodiversity and Proteinaceous Components of Venom Nukhba Akbar1,2*, Ashif Sajjad1, Sabeena Rizwan2, Sobia Munir2, Khalid Mehmood1, Syeda Ayesha Ali2, Rakhshanda2, Ayesha Mushtaq2, Hamza Zahid3 1Institute of Biochemistry, Faculty of Life sciences, University of Balochistan, Quetta, Pakistan 2Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Life Sciences, Sardar Bahadur Khan Women’s University Quetta, Pakistan 3Bolan Medical College, Quetta, Pakistan Key words: Scorpion, Envenomation, Protein, Toxins, Anti-microbial. http://dx.doi.org/10.12692/ijb/18.2.146-162 Article published on February 26, 2021 Abstract Scorpions are a primitive and vast group of venomous arachnids. About 2200 species have been recognized so far. Besides, only a small section of species is considered disastrous to humans. The pathophysiological complications related to a single sting of scorpion are noteworthy to recognize scorpion's envenomation as a universal health problem. The medical relevance of the scorpion's venom attracts modern era research. By molecular cloning and classical biochemistry, several proteins and peptides (related to toxins) are characterized. The revelation of many other novel components and their potential activities in different fields of biological and medicinal sciences revitalized the interests in the field of scorpion‟s venomics. The current study contributes and attempts to escort some general information about the composition of scorpion's venom mainly related to the proteins/peptides. Also, the diverse pernicious effects of scorpion's sting due to the numerous neuro-toxins, hemolytic toxins, nephron-toxins and cardio-toxins as well as the contribution of such toxins/peptides as a potential source of anti-microbial and anti-cancer therapeutics are also covered in the present review. -

Scorpiones: Euscorpiidae) from a Dinaric Cave - the First Record of Troglobite Scorpion in European Fauna

Biologia Serbica, 2020, 42: 0-0 DOI 10.5281/zenodo.4013425 Original paper A new Euscorpius species (Scorpiones: Euscorpiidae) from a Dinaric cave - the first record of troglobite scorpion in European fauna Ivo KARAMAN1, 2 1University of Novi Sad, Faculty of Sciences, Department of Biology and Ecology, Trg Dositeja Obradovića 2, 21000 Novi Sad, Serbia 2Serbian Biospeleological Society, Trg Dositeja Obradovića 2, 21000 Novi Sad, Serbia Received: 23 June 2020 / Accepted: 13 August 2020 / Summary. A troglobite, Euscorpius studentium n. sp. is described based on a single immature male specimen from Skožnica, a relatively small cave in the coastal region of Montenegro. The characteristics of the new species are compared with the characteristics of an immature male specimen of troglophile Euscorpius feti Tropea, 2013 of the same size, from another cave in Montenegro. Some identified differences indicate evolutionary changes that are the result of the process of adaptation of troglobite scorpions for life under conditions found in underground habitats: reduced eyes, depigmentation, smooth teguments with reduced granulation and tubercles, elongated sharp and thin ungues of the legs and narrowed body. The settlement of limestone caves by large troglobionts such as scorpions fol- lows karstification processes. Lithophilic forms that evolved under these conditions possess the necessary climbing abilities that are prerequisite for settlement of hypogean habitats. Uncontrolled visits by tourists in recent years have seriously threatened the fauna of Skožnica cave, including this new and first recognized troglobite scorpion species among European fauna. Keywords: edaphomorphic, Montenegro, troglobite, troglomorphic, troglophile. INTRODUCTION the existence of troglobites. I think there are two reasons that cave scorpions have not been recorded to date in Dinaric Dinaric karst is famous as a global hot spot of subter- karst. -

Acarología Y Aracnología

ACAROLOGÍA Y ARACNOLOGÍA LOS ALACRANES DEL MUNICIPIO DE CHILAPA DE ÁLVAREZ DEL ESTADO DE GUERRERO, MEXICO José Guadalupe Baldazo-Monsivaiz1, Miguel Flores-Moreno2, Ascencio Villegas-Arrizón2, Alejandro Balanzar- Martínez2, Arcadio Morales-Pérez2 y Elizabeth Nava-Aguilera2. 1Unidad Académica Preparatoria No. 13, Universidad Autónoma de Guerrero. Av. Universidad S/N Col. El Limón, 40880, Zihuatanejo, Guerrero, México. Tel. 7555542950. [email protected]. 2Centro de Investigación de Enfermedades Tropicales, Universidad Autónoma de Guerrero. Av. Pino s/n, Colonia El Roble, 39640, Acapulco, Guerrero, México. [email protected] RESUMEN. El estado de Guerrero, debido a su relieve topográfico, presenta una gran diversidad de biomas y por lo tanto una alta biodiversidad de flora y fauna, que también se ve reflejada en la aracnofauna, en la cual los alacranes, ocasionan problemas de salud pública importantes en el estado, razón por la que se desarrolló el proyecto “Estrategias para disminuir la densidad de alacranes y picadura de alacrán dentro del hogar, en el municipio de Chilapa de Álvarez, Guerrero”. Se realizaron muestreos en el interior de las casas y patios de nueve comunidades previamente seleccionadas aleatoriamente posterior a estratificación. Se capturaron siete especies de alacranes, cuatro ya conocidas y tres nuevas para la ciencia. Palabras clave: alacranes, Centruroides, Vaejovis, Guerrero, México. ABSTRACT. The state of Guerrero presents a great biodiversity of flora and fauna due to its topographic relief and diversity of biomes. These environmental conditions are reflected in arachnid diversity. The scorpions within the arachnids are cause of important problems of public health in the estate of Guerrero and therefore the project “Strategies to diminish the density and mobility of scorpion bites inside the home, in the municipality of Chilapa de Alvarez, Guerrero” was developed. -

Prendini.2010.Pdf

Cladistics Cladistics 26 (2010) 117–142 10.1111/j.1096-0031.2009.00277.x Troglomorphism, trichobothriotaxy and typhlochactid phylogeny (Scorpiones, Chactoidea): more evidence that troglobitism is not an evolutionary dead-end Lorenzo Prendinia,*, Oscar F. Franckeb and Valerio Vignolic aDivision of Invertebrate Zoology, American Museum of Natural History, Central Park West at 79th Street, New York, NY 10024-5192, USA; bDepartmento de Zoologia, Instituto de Biologı´a, Universidad Nacional Auto´noma de Me´xico, Apto Postal 70-153, Coyoaca´n, 04510 Me´xico; cDepartment of Evolutionary Biology, University of Siena, Via Aldo Moro 2-53100, Siena, Italy Accepted 8 May 2009 Abstract The scorpion family Typhlochactidae Mitchell, 1971 is endemic to eastern Mexico and exclusively troglomorphic. Six of the nine species in the family are hypogean (troglobitic), morphologically specialized for life in the cave environment, whereas three are endogean (humicolous) and comparably less specialized. The family therefore provides a model for testing the hypotheses that ecological specialists (stenotopes) evolve from generalist ancestors (eurytopes) and that specialization (in this case to the cavernicolous habitat) is an irreversible, evolutionary dead-end that ultimately leads to extinction. Due to their cryptic ecology, inaccessible habitat, and apparently low population density, Typhlochactidae are very poorly known. The monophyly of these troglomorphic scorpions has never been rigorously tested, nor has their phylogeny been investigated in a quantitative analysis. We test and confirm their monophyly with a cladistic analysis of 195 morphological characters (142 phylogenetically informative), the first for a group of scorpions in which primary homology of pedipalp trichobothria was determined strictly according to topographical identity (the ‘‘placeholder approach’’). -

Scorpion Venom: a Poison Or a Medicine-Mini Review

Indian Journal of Geo Marine Sciences Vol. 47 (04), April 2018, pp. 773-778 Review Article Scorpion venom: A poison or a medicine-mini review Pir Tariq Shah1, Farooq Ali1, Noor-Ul-Huda1, Sadia Qayyum1, Shehzad Ahmed1, Kashif Syed Haleem1, Isfahan Tauseef1, Mujaddad-ur-Rehman2, Azam Hayat2, Attiya Abdul Malik2, Rahdia Ramzan2 & Ibrar Khan1,2* 1Department of Microbiology, Hazara University, 21300 Mansehra, Pakistan 2Department of Microbiology, Abbottabad University of Science & Technology, 2250 Havelian, Pakistan *[E-mail: [email protected] ] Received 16 June 2016 ; revised 27 July 2016 The Scorpion’s venom considered to be highly complex mixture of nucleotides, enzymes, mucoproteins, biogenic amines, salts, as well as peptides and proteins, which have been used in traditional medicine for thousands of years mainly in Asia and Africa. With the significant discoveries in the number of valuable biologically active components of scorpion venom, numerous drug candidates have been found with the potential to encounter many of the emerging global health crisis. This mini-review sheds light on the application of scorpion venoms and toxins as potential novel antibacterial, antifungal and antiviral, especially as anticancer therapeutics. [Keywords: Scorpion venom, Antibacterial, Antifungal, Antiviraland Anticancer Potential.] Introduction Scorpion Venomous animals are famous only for their Scorpions are the predatory arachnids and members adverse effects caused after interaction with humans of the order scorpiones. They have eight legs, a accidently. These creatures transmit variety of narrow, segmented tail curved over the body, with a detrimental toxins with diverse physiological poisonous stinger at the end. Size ranges from 9 mm activities that may either lead to minor symptoms like to 20 cm (Typhlochactas mitchelli and Hadogenes dermatitis and allergic responses or highly severe troglodytes respectively)2. -

A New Species of Troglomorphic Leaf Litter Scorpion from Colombia Belonging to the Genus Troglotayosicus

Botero-Trujillo, Ricardo, and Oscar F. Francke. 2009. A new species of troglomorphic leaf litter scorpion from Colombia belonging to the genus Troglotayosicus (Scorpiones: Troglotayosicidae) [Nueva especie de escorpión troglomórfico de hojarasca de Colombia perteneciente al género Troglotayosicus (Scorpiones: Troglotayosicidae)]. Texas Memorial Museum Speleological Monographs, 7. Studies on the cave and endogean fauna of North America, V. Pp. 1-10. A NEW SPECIES OF TROGLOMORPHIC LEAF LITTER SCORPION FROM COLOMBIA BELONGING TO THE GENUS TROGLOTAYOSICUS (SCORPIONES: TROGLOTAYOSICIDAE) Ricardo Botero-Trujillo Laboratorio de Entomología, Unidad de Ecología y Sistemática, Departamento de Biología, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Bogotá, Colombia. Email: [email protected] and Oscar F. Francke Colección Nacional de Arácnidos, Departamento de Zoología, Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Apartado Postal 70-153, México D. F. 04510, México. Email: [email protected] RESUMEN ABSTRACT Se describe Troglotayosicus humiculum, n. sp., con base a un Troglotayosicus humiculum, n. sp., is described from a ejemplar colectado con trampa Winkler en la Reserva Natural La specimen collected by Winkler trap in La Planada Natural Reserve, Planada, Departamento de Nariño, Colombia suroccidental. Con esta Nariño Department, southwestern Colombia. With this description, descripción, el número de especies descritas y ejemplares conocidos both the number of described species and known specimens in the en el género se incrementa a dos. La nueva especie habita en genus is raised to two. The new species was collected from leaf hojarasca, en lugar de una cueva como la única otra especie conocida, litter, rather than inside a cave as was the only other known species, Troglotayosicus vachoni Lourenço, 1981; y difiere de esta Troglotayosicus vachoni Lourenço, 1981; and differs from it particularmente en la disposición de sedas ventrales de los telotarsos particularly in the arrangement of the ventral setae of the telotarsi y la carinación del metasoma. -

UG ETD Template

Exploring genome size diversity in arachnid taxa by Haley Lauren Yorke A Thesis presented to The University of Guelph In partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Integrative Biology Guelph, Ontario, Canada © Haley L. Yorke, January, 2020 ABSTRACT EXPLORING GENOME SIZE DIVERSITY IN ARACHNID TAXA Haley L. Yorke Advisor(s): University of Guelph, 2019 Dr. T. Ryan Gregory This study investigates the general ranges and patterns of arachnid genome size diversity within and among major arachnid groups, with a focus on tarantulas (Theraphosidae) and scorpions (Scorpiones), and an examination of how genome size relates to body size, growth rate, longevity, and geographical latitude. I produced genome size measurements for 151 new species, including 108 tarantulas (Theraphosidae), 20 scorpions (Scorpiones), 17 whip-spiders (Amblypygi), 1 vinegaroon (Thelyphonida), and 5 non-arachnid relatives – centipedes (Chilopoda). I also developed a new methodology for non-lethal sampling of arachnid species that is inexpensive and portable, which will hopefully improve access to live specimens in zoological or hobbyist collections. I found that arachnid genome size is positively correlated with longevity, body size and growth rate. Despite this general trend, genome size was found to negatively correlate with longevity and growth rate in tarantulas (Theraphosidae). Tarantula (Theraphosidae) genome size was correlated negatively with latitude. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This study would not have been possible without access to specimens from the collections of both Amanda Gollaway and Martin Gamache of Tarantula Canada, and also of Patrik de los Reyes – thank you for trusting me with your valuable and much- loved animals, for welcoming me into your homes and places of business, and for your expert opinions on arachnid husbandry and biology. -

Acarología Y Aracnología

ACAROLOGÍA Y ARACNOLOGÍA LOS ALACRANES DEL MUNICIPIO DE CHILAPA DE ÁLVAREZ DEL ESTADO DE GUERRERO, MEXICO José Guadalupe Baldazo-Monsivaiz1, Miguel Flores-Moreno2, Ascencio Villegas-Arrizón2, Alejandro Balanzar- Martínez2, Arcadio Morales-Pérez2 y Elizabeth Nava-Aguilera2. 1Unidad Académica Preparatoria No. 13, Universidad Autónoma de Guerrero. Av. Universidad S/N Col. El Limón, 40880, Zihuatanejo, Guerrero, México. Tel. 7555542950. [email protected]. 2Centro de Investigación de Enfermedades Tropicales, Universidad Autónoma de Guerrero. Av. Pino s/n, Colonia El Roble, 39640, Acapulco, Guerrero, México. [email protected] RESUMEN. El estado de Guerrero, debido a su relieve topográfico, presenta una gran diversidad de biomas y por lo tanto una alta biodiversidad de flora y fauna, que también se ve reflejada en la aracnofauna, en la cual los alacranes, ocasionan problemas de salud pública importantes en el estado, razón por la que se desarrolló el proyecto “Estrategias para disminuir la densidad de alacranes y picadura de alacrán dentro del hogar, en el municipio de Chilapa de Álvarez, Guerrero”. Se realizaron muestreos en el interior de las casas y patios de nueve comunidades previamente seleccionadas aleatoriamente posterior a estratificación. Se capturaron siete especies de alacranes, cuatro ya conocidas y tres nuevas para la ciencia. Palabras clave: alacranes, Centruroides, Vaejovis, Guerrero, México. ABSTRACT. The state of Guerrero presents a great biodiversity of flora and fauna due to its topographic relief and diversity of biomes. These environmental conditions are reflected in arachnid diversity. The scorpions within the arachnids are cause of important problems of public health in the estate of Guerrero and therefore the project “Strategies to diminish the density and mobility of scorpion bites inside the home, in the municipality of Chilapa de Alvarez, Guerrero” was developed. -

Macrofauna – Coleoptera

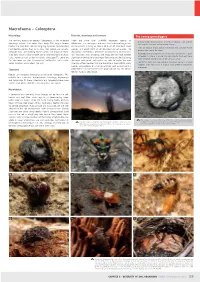

Macrofauna – Coleoptera Morphology Diversity, abundance and biomass The caring gravediggers The defining feature of beetles (Coleoptera) is the hardened There are more than 370 000 described species of • Burying beetles bury carcasses of small vertebrates, such as birds forewings (elytra) that cover their body. The largest known Coleoptera – it is the largest and most diverse order of organisms and rodents, as a food source for their larvae. beetles are more than 160 mm long (e.g. Dynastes hercules), but on the planet, making up about 40 % of all described insect • They are unusual among insects in that both the male and female most beetles are less than 5 mm long. Their colours are variable, species, and about 30 % of all described animal species. The parents take care of the brood. although most soil-dwelling beetle species are brown or black. abundance and biomass of beetles on ephemeral and nutrient- Their body shape is also variable: some have long horns or sharp rich resources, such as carrion and dung, are very high. Beetles • Although parental responsibilities are usually carried out by a couple of beetles, a male or a female may also care for the brood alone, tusks, some can curl up like myriapods (see page 57), some are significantly contribute to decomposition processes. Besides being when the other partner is lost or the carcass is small. flat and some are slim. A number of soil beetles, such as the abundant and varied, soil beetles are able to exploit the wide • Sometimes more than two unrelated individuals can raise a brood genus Carabus, are wingless. -

Evolution of Scorpion Orthobothriotaxy: a Cladistic Approach

Euscorpius Occasional Publications in Scorpiology EDITOR: Victor Fet, Marshall University, ‘[email protected]’ ASSOCIATE EDITOR: Michael E. Soleglad, ‘[email protected]’ Euscorpius is the first research publication completely devoted to scorpions (Arachnida: Scorpiones). Euscorpius takes advantage of the rapidly evolving medium of quick online publication, at the same time maintaining high research standards for the burgeoning field of scorpion science (scorpiology). Euscorpius is an expedient and viable medium for the publication of serious papers in scorpiology, including (but not limited to): systematics, evolution, ecology, biogeography, and general biology of scorpions. Review papers, descriptions of new taxa, faunistic surveys, lists of museum collections, and book reviews are welcome. Derivatio Nominis The name Euscorpius Thorell, 1876 refers to the most common genus of scorpions in the Mediterranean region and southern Europe (family Euscorpiidae). Euscorpius is located on Website ‘http://cos-server.marshall.edu/euscorpius’ at Marshall University, Huntington, WV 25755-2510, USA. The International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN, 4th Edition, 1999) does not accept online texts as published work (Article 9.8); however, it accepts CD-ROM publications (Article 8). Euscorpius is produced in two identical versions: online (ISSN 1536-9307) and CD-ROM (ISSN 1536-9293). Only copies distributed on a CD-ROM from Euscorpius are considered published work in compliance with the ICZN, i.e. for the purposes of new names and new nomenclatural