Selected Birth Defects Data from Population-Based Birth Defects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Differential Diagnosis of Pulmonic Stenosis by Means of Intracardiac Phonocardiography

Differential Diagnosis of Pulmonic Stenosis by Means of Intracardiac Phonocardiography Tadashi KAMBE, M.D., Tadayuki KATO, M.D., Norio HIBI, M.D., Yoichi FUKUI, M.D., Takemi ARAKAWA, M.D., Kinya NISHIMURA,M.D., Hiroshi TATEMATSU,M.D., Arata MIWA, M.D., Hisao TADA, M.D., and Nobuo SAKAMOTO,M.D. SUMMARY The purpose of the present paper is to describe the origin of the systolic murmur in pulmonic stenosis and to discuss the diagnostic pos- sibilities of intracardiac phonocardiography. Right heart catheterization was carried out with the aid of a double- lumen A.E.L. phonocatheter on 48 pulmonic stenosis patients with or without associated heart lesions. The diagnosis was confirmed by heart catheterization and angiocardiography in all cases and in 38 of them, by surgical intervention. Simultaneous phonocardiograms were recorded with intracardiac pressure tracings. In valvular pulmonic stenosis, the maximum ejection systolic murmur was localized in the pulmonary artery above the pulmonic valve and well transmitted to both right and left pulmonary arteries, the superior vena cava, and right and left atria. The maximal intensity of the ejection systolic murmur in infundibular stenosis was found in the outflow tract of right ventricle. The contractility of the infundibulum greatly contributes to the formation of the ejection systolic murmur in the outflow tract of right ventricle. In tetralogy of Fallot, the major systolic murmur is caused by the pulmonic stenosis, whereas the high ventricular septal defect is not responsible for it. In pulmonary branch stenosis, the sys- tolic murmur was recorded distally to the site of stenosis. Intracardiac phonocardiography has proved useful for the dif- ferential diagnosis of various types of pulmonic stenosis. -

Coarctation of the Aorta Interrupted Aortic Arch

T HE P EDIATRIC C ARDIAC S URGERY I NQUEST R EPORT Coarctation of the aorta In the normal heart, blood flows to the body through the aorta, which connects to the left ven- tricle and arches over the top of the heart.In coarc- tation of the aorta,the aorta is pinched (in medical terms, coarcted) at a point somewhere along its length. This pinching restricts blood flow from the heart to the rest of the body. Often, the baby also has other heart defects, such as a narrowing of the aortic arch (in medical terms,transverse aortic arch hypoplasia). Usually no symptoms are apparent at birth, but can develop within a week of birth with the closure of the ductus arteriosus. The possible conse- Diagram 2.9 Coarctation of the aorta quences of this condition are poor feeding, an 1 – pinched or coarcted aorta enlarged heart, an enlarged liver and congestive Flow patterns are normal but are reduced below the coarctation. Blood pressure is increased in ves- heart failure. Blood pressure also increases above sels leaving the aorta above the coarctation. The the constriction. broken white arrow indicates diminished blood flow through the aorta. Timing of surgery depends on the degree of coarctation. Surgery may be delayed with mild coarctation (which sometimes is not detected until adoles- cence). However, if a baby develops congestive heart failure or high blood pressure, early surgery is usually required. A baby with severe coarctation should have early surgery to prevent long-term high blood pres- sure. The coarctation can be repaired in a number of ways without opening the heart.The surgeon can remove the narrowed part of the aorta and sew the ends together, thereby creating an anastomosis. -

Pulmonary-Atresia-Mapcas-Pavsdmapcas.Pdf

Normal Heart © 2012 The Children’s Heart Clinic NOTES: Children’s Heart Clinic, P.A., 2530 Chicago Avenue S, Ste 500, Minneapolis, MN 55404 West Metro: 612-813-8800 * East Metro: 651-220-8800 * Toll Free: 1-800-938-0301 * Fax: 612-813-8825 Children’s Minnesota, 2525 Chicago Avenue S, Minneapolis, MN 55404 West Metro: 612-813-6000 * East Metro: 651-220-6000 © 2012 The Children’s Heart Clinic Reviewed March 2019 Pulmonary Atresia, Ventricular Septal Defect and Major Aortopulmonary Collateral Arteries (PA/VSD/MAPCAs) Pulmonary atresia (PA), ventricular septal defect (VSD) and major aortopulmonary collateral arteries (MAPCAs) is a rare type of congenital heart defect, also referred to as Tetralogy of Fallot with PA/MAPCAs. Tetralogy of Fallot (TOF) is the most common cyanotic heart defect and occurs in 5-10% of all children with congenital heart disease. The classic description of TOF includes four cardiac abnormalities: overriding aorta, right ventricular hypertrophy (RVH), large perimembranous ventricular septal defect (VSD), and right ventricular outflow tract obstruction (RVOTO). About 20% of patients with TOF have PA at the infundibular or valvar level, which results in severe right ventricular outflow tract obstruction. PA means that the pulmonary valve is closed and not developed. When PA occurs, blood can not flow through the pulmonary arteries to the lungs. Instead, the child is dependent on a patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) or multiple systemic collateral vessels (MAPCAs) to deliver blood to the lungs for oxygenation. These MAPCAs usually arise from the de- scending aorta and subclavian arteries. Commonly, the pulmonary arteries are abnormal, with hypoplastic (small and underdeveloped) central and branch pulmonary arteries and/ or non-confluent central pulmonary arteries. -

Prenatal Diagnosis, Associated Findings and Postnatal Outcome Of

J. Perinat. Med. 2019; 47(3): 354–364 Ingo Gottschalka,*, Judith S. Abela, Tina Menzel, Ulrike Herberg, Johannes Breuer, Ulrich Gembruch, Annegret Geipel, Konrad Brockmeier, Christoph Berg and Brigitte Strizek Prenatal diagnosis, associated findings and postnatal outcome of fetuses with double outlet right ventricle (DORV) in a single center https://doi.org/10.1515/jpm-2018-0316 anomalies, 30 (66.7%) had extracardiac anomalies and 13 Received September 18, 2018; accepted November 26, 2018; (28.9%) had chromosomal or syndromal anomalies. Due previously published online December 20, 2018 to their complex additional anomalies, five (11.1%) of our Abstract 45 fetuses had multiple malformations and were highly suspicious for non-chromosomal genetic syndromes, Objective: To assess the spectrum of associated anoma- although molecular diagnosis could not be provided. Dis- lies, the intrauterine course, postnatal outcome and orders of laterality occurred in 10 (22.2%) fetuses. There management of fetuses with double outlet right ventricle were 17 terminations of pregnancy (37.8%), two (4.4%) (DORV). intrauterine and seven (15.6%) postnatal deaths. Nineteen Methods: All cases of DORV diagnosed prenatally over a of 22 (86.4%) live-born children with an intention to treat period of 8 years were retrospectively collected in a single were alive at last follow-up. The mean follow-up among tertiary referral center. All additional prenatal findings survivors was 32 months (range, 2–72). Of 21 children who were assessed and correlated with the outcome. The accu- had already undergone postnatal surgery, eight (38.1%) racy of prenatal diagnosis was assessed. achieved biventricular repair and 13 (61.9%) received Results: Forty-six cases of DORV were diagnosed pre- univentricular palliation. -

Tetralogy of Fallot: Stroke in a Young Patient

Open Access Case Report DOI: 10.7759/cureus.2714 Tetralogy of Fallot: Stroke in a Young Patient Hassam Ali 1 , Shiza Sarfraz 2 , Muhammad Sanan 1 1. Medical 4, Bahawal Victoria Hospital, Quaid-E-Azam Medical College, Bahawalpur, PAK 2. Department of Anesthesiology, Bahawal Victoria Hospital, Quaid-E-Azam Medical College, Bahawalpur, PAK Corresponding author: Hassam Ali, [email protected] Abstract Tetralogy of Fallot (TOF) is a congenital birth defect of the heart which actually comprises four individual flaws. It causes poor flow of oxygenated blood to the organs and leads to cyanosis (blue-tinted skin, because of inadequate oxygenation). It can be recognized at birth or in adulthood. But sometimes, cases may go unnoticed, and the patient might present with some rare complications. In this case, the patient presented with an embolic infarct of the brain at the age of 25 with an undiagnosed tetralogy of Fallot. Categories: Cardiology, Internal Medicine, Neurology Keywords: congenital heart defects, embolic stroke, tetralogy of fallot, paralysis, cardiology, cerebrovascular accident, heart, neurology, international medicine Introduction Tetralogy of Fallot (TOF) is a heart disease present at birth [1]. It consists of four defects [2]: - Pulmonary stenosis - Ventricular septal defect - Right ventricular hypertrophy - Aorta overriding the ventricular septal defect Some babies, when they cry or breastfeed, may turn very blue. This is because of "a tet spell" due to the shunting of excess deoxygenated blood from the right chamber of the heart to the left chamber. Such babies may have difficulty breathing, become limp, or even lose consciousness [3]. TOF is treated by open-heart surgery, mostly in the first year of life. -

Trilogy of Fallot in a Dog

J Vet Clin 29(5) : 404-407 (2012) Trilogy of Fallot in a Dog Ran Choi, Hyo-Jin Ahn and Changbaig Hyun1 Section of Small Animal Internal Medicine, College of Veterinary Medicine, Kangwon National University, Chuncheon 201-100, Korea (Accepted: October 05, 2012) Abstract : A 3 years-old female mixed dog (weighing 5.3 kg) was referred to veterinary teaching hospital of Kangwon National University with primary complaints of syncope, severe exercise intolerance, depression and lethargy. Diagnostic studies revealed polycythemia, right sided cardiac enlargement on thoracic radiography and right-to left atrial septal defect, severe pulmonary stenosis (~5 m/s of peak velocity) and right ventricular hypertrophy. Based on diagnostic findings, the dog was diagnosed as trilogy of Fallot. To improve clinical condition of this dog, diltiazem and enalapril were prescribed with weekly phlebotomy. To author’s best knowledge, this is the first case of trilogy of Fallot in Korea. Key words : trilogy of Fallot, atrial septal defects, pulmonic stenosis, right ventricular hypertrophy, CHD. Introduction ring veterinarian, the dog had history of cardiac murmur after birth and occasional syncopal episodes (increasing frequency Trilogy of Fallot is a compound congenital heart defects recently). On the physical examination, the dog had grade 2/6 (CHD) comprised of pulmonary stenosis, atrial septal dys- mild systolic murmur at right apex and left base of heart. The morphogenesis (e.g. atrial septal defect and patent foramen systolic blood pressure measured by Doppler method was ovale) and right ventricular hypertrophy (1). The CHD are 100-110 mmHg. broadly classified into cyanotic CHD and non-cyanotic CHD. -

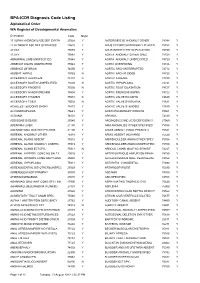

BPA-ICD9 Diagnosis Code Listing Alphabetical Order WA Register of Developmental Anomalies

BPA-ICD9 Diagnosis Code Listing Alphabetical Order WA Register of Developmental Anomalies Description Code Major 17 ALPHA HYDROXYLASE DEF SYNTH25524 Y ANTERIOR EYE ANOMALY OTHER74348 Y 21 HYDROXYLASE DEF SYNTHESIS25520 Y ANUS ECTOPIC/ANTERIORLY PLACED75153 Y 47,XXX 75885 Y ANUS/INTEST/CYST DUPLICATION75150 Y 47,XYY 75884 Y AORTA ANOMALY OTHER SPEC74728 Y ABNORMAL LIMB UNSPECIFIED75548 Y AORTA ANOMALY UNSPECIFIED74729 Y ABSENCE DIGITS UNSPECIFIED75544 Y AORTA OVERRIDING 74726 Y ABSENCE OF BRAIN 74000 Y AORTIC ARCH INTERRUPTED 74712 Y ABSENT NIPPLE 75763 N AORTIC ARCH R SIDED 74723 Y ACCESSORY AURICLE/S 74410 N AORTIC ATRESIA 74720 Y ACCESSORY DIGIT/S UNSPECIFIED75509 N AORTIC HYPOPLASIA 74721 Y ACCESSORY FINGER/S 75500 N AORTIC ROOT DILATATION 74727 Y ACCESSORY HAND/FOREARM 75504 Y AORTIC STENOSIS SUPRA 74722 Y ACCESSORY THUMB/S 75501 N AORTIC VALVE BICUSPID 74640 Y ACCESSORY TOE/S 75502 N AORTIC VALVE DYSPLASIA 74631 Y ACHILLES TENDON/S SHORT 75472 Y AORTIC VALVE STENOSIS 74630 Y ACHONDROPLASIA 75643 Y AORTOPULMONARY WINDOW 74501 Y ACRANIA 74001 Y APHAKIA 74330 Y ADDISONS DISEASE 25540 Y ARGINOSUCCINIC ACID DEFICIENCY27060 Y ADENOMA LIVER 21150 Y ARM ANOMALIES OTHER SPECIFIED75556 Y ADENOMYOMA GASTRIC PYLORIS21100 Y ARM/S ABSENT (HAND PRESENT)75521 Y ADRENAL ANOMALY OTHER 75918 Y ARM/S ABSENT (NO HAND) 75520 Y ADRENAL GLAND ABSENT 75910 Y ARM/SHOULDER ANOM OTHER SPEC75558 Y ADRENAL GLAND ANOMALY UNSPEC75919 Y ARM/SHOULDER ANOM UNSPECIFIED75559 N ADRENAL GLAND ECTOPIC 75913 N ARNOLD CHIARI MALF NO SPIN BIF74227 Y ADRENAL HYPERPL CONG NO -

Double Outlet Right Ventricle (DORV)

Double outlet right ventricle (DORV) Vita Zīdere, MD FRCP Consultant Paediatric and Fetal Cardiologist • Complex lesion, represents 3 % of CHD seen in fetus • Both Great Arteries arise completely or predominantly from the morphological right ventricle • Associates with increased NT, genetic and extracardiac anomalies • Double outlet right ventricle is a spectrum of abnormalities • almost always has a VSD • heterogeneous with respect to size and position of VSD and relationship of GA • individual anatomy dictates surgical approach and outcome • It poses a number of challenges • Definition • Anatomic Variability (incl. normal or abnormal AV connections) • Surgical options DORV TOF type DORV “Simple” DORV Complex DORV Always VSD: Unbalanced Ventricles AVSD (often RAI or LAI) subaortic, MV atresia subpulmonary or uncommitted; Coarctation, IAA +/-PS Discordant AV connections Criss-cross heart Normal atrial situs Patent, concordant AV connections DORV Overriding aorta Both GA (parallel) from RV “50 % rule” Subpulmonary, subaortic or uncommitted VSD TOF type DORV Anatomical repair- Repair depends from GA relationship with VSD VSD closure & PS release LV to Ao baffle ASO with baffling VSD to neo-Ao Rarely BV repair is unfeasible L G Price 2004 G Price • True override is independent of septal axis • postnatally is assessed relative to chord of circle in short axis* *BR Wilcox, AC Cook, RH Anderson. Surgical anatomy of the heart,2004 Double Outlet Right ventricle v. Tetralogy of Fallot L L R R • Perimembranous VSD, overriding aorta • Pulmonary artery -

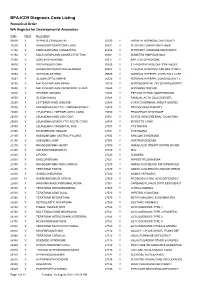

BPA-ICD9 Diagnosis Code Listing Numerical Order WA Register for Developmental Anomalies

BPA-ICD9 Diagnosis Code Listing Numerical Order WA Register for Developmental Anomalies Code Major Description 09090 Y SYPHILIS CONGENITAL 25330 Y GROWTH HORMONE DEFICIENCY 16200 Y RHABDOMYOSARCOMA LUNG 25331 Y PITUITARY DWARFISM OTHER 17100 Y FIBROSARCOMA CONGENITAL 25342 Y PITUITARY HORMONE DEFICIENCY 17190 Y MALIG NEOPLASM CONNECTIVE TISS 25351 Y DIABETES INSIPIDUS NOS 17300 Y GORLIN SYNDROME 25511 Y BARTTER SYNDROME 18690 Y ORCHIOBLASTOMA 25520 Y 21 HYDROXYLASE DEF SYNTHESIS 18900 Y RHABDOMYOSARCOMA BLADDER 25524 Y 17 ALPHA HYDROXYLASE DEF SYNTH 19050 Y RETINOBLASTOMA 25525 Y ADRENAL HYPERPL CONG SALT LOSS 19051 Y GLIOMA OPTIC NERVE 25526 Y ADRENAL HYPERPL CONG NO SALT L 19100 Y MALIG NEOPLASM BRAIN 25529 Y ADRENOGENTIAL DIS OTHER&UNSPEC 19400 Y MALIG NEOPLASM ENDOCRINE GLAND 25540 Y ADDISONS DISEASE 19410 Y NEUROBLASTOMA 25543 Y PSEUDO HYPOALDOSTERONISM 19500 Y GLIOMA NASAL 25548 Y FAMILIAL ACTH (GLUCOID DEF) 20250 Y LETTERER-SIWE DISEASE 25549 Y CORTICOADRENAL INSUFF UNSPEC 20290 Y HAEMOPHAGOCYTIC LYMPHOHISTIOCY 25910 Y PRECOCIOUS PUBERTY 20400 Y LEUKAEMIA LYMPHOBLASTIC CONG 25980 Y PROGEROID SYNDROME 20500 Y LEUKAEMIA MYELOID CONG 25981 Y SOTOS SYN/CEREBRAL GIGANTISM 20600 Y LEUKAEMIA MONOCYTIC ACUTE CONG 26800 Y RICKETTS CONG 20890 Y LEUKAEMIA CONGENITAL NOS 27000 Y CYSTINOSIS 21000 Y MYOFIBROMA TONGUE 27001 Y CYSTINURIA 21100 Y ADENOMYOMA GASTRIC PYLORIS 27002 Y FANCONI SYNDROME 21150 Y ADENOMA LIVER 27003 Y HARTNUP DISEASE 21270 Y RHABDOMYOMA HEART 27009 Y AMINO-ACID TRNSPT DISTRB OTHER 21300 Y OSTEOCHONDROMATA 27010 Y PKU 21400 -

The Clinical Evolution of Shunt-Operations for Morbus Caeruleus: Results of 150 Operations, in a Long-Term Follow-Up

The Clinical Evolution of Shunt-Operations for Morbus Caeruleus: Results of 150 Operations, in a Long-Term Follow-Up C. A. Mahuim, M.D., C.L.C. van Nieuwenhuizen, M.D., H.A.H. D’heer, M.D., and F. Sloojj, M.D., Utrecht, Netherlands INTRODUCTION The classical operations of Blalock,4 Potts,25 and Brocks which have been used for more than 10 years in treating the tetralogy of Fallot are purely symp- tomatic. Their aim is to augment the pulmonary circulation in order to increase the oxygenation of the blood. However, they do not, properly speaking, correct the malformation. In fact, with the procedures of Blalock and Potts a fifth malformation is created in a heart that already has four. It is well known that an operation which creates an artificial ductus arteriosus must, in the long run, produce a significant overloading of the heart. In any event, the immediate benefits of the operation, in so far as the general status of the patients and the amelioration of the cyanosis are concerned, are so evident that the undeniable usefulness of this type of operation is universally recognized. TABLE I GOOD AUTHOR AND NUMBER PROCEDURE USED (IN OVER-ALL I UZSULTS YEAR OF ORDEROFFREQUENCY) MORTALITY (PER FOLLOW-UP PATIENTS (PER CENT) CENT) -- Potts, 1956 514 Potts 9 ? ? Johnson, 1951 144 Blalock, Potts 12 ? ? Bret, 1952 172 Potts, Blalock, Brock 20 i Derra, 1952 242 Blalock. Brock 19 7’: ? Dubost, 1954 333 Blalock; Potts, Brock 16 78 ? Brock, 1955 140 Brock 11.5 ? Sellers, 1950 Blalock, Potts, Brock 10.5 E.5 6 mo. -

Cardiac Surgery Was Performed Under Beating Heart

This article appeared in a journal published by Elsevier. The attached copy is furnished to the author for internal non-commercial research and education use, including for instruction at the authors institution and sharing with colleagues. Other uses, including reproduction and distribution, or selling or licensing copies, or posting to personal, institutional or third party websites are prohibited. In most cases authors are permitted to post their version of the article (e.g. in Word or Tex form) to their personal website or institutional repository. Authors requiring further information regarding Elsevier’s archiving and manuscript policies are encouraged to visit: http://www.elsevier.com/copyright Author's personal copy Review REVIEW On-pump Beating Heart Surgery Ansheng Mo, MD a,∗ and Hui Lin, MD a,b a Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, The People’s Hospital of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, Nanning 530021, China b The People’s Hospital of Wuhan University, Wuhan, China On-pump beating heart surgery has been proposed as a superior technique for cardiac surgery, and is receiving renewed interest from cardiac surgeons. Here, we review the technique, focusing on the basic principles of myocardial protection, operative methodology, category, intraoperative concerns, current status, organ protection, advantages, disadvantages, indications, contraindications, unanswered questions, and future research. (Heart, Lung and Circulation 2011;20:295–304) © 2011 Australasian Society of Cardiac and Thoracic Surgeons and the Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Keywords. On-pump; Beating heart; Ischaemia–reperfusion Introduction Feasibility of Surgery on the Empty Beating Heart ardiac surgery was performed under beating heart Myocardial Protection C or ventricular fibrillation conditions prior to the During on-pump beating heart surgery, the oxygen advent of cardioplegia, which made surgery easier. -

CYANOTIC CONGENITAL HEART DISEASE by JAMES W

.-51.I Postgrad Med J: first published as 10.1136/pgmj.25.289.511 on 1 November 1949. Downloaded from CYANOTIC CONGENITAL HEART DISEASE By JAMES W. BROWN, M.D., F.R.C.P. Physician, General Hospital, Grimsby, and Grimsby and Lindsey Rheumatism and Heart Clinics The last 15 years have witnessed a very re- it was possible to build up a clinical picture and so markable change in the attitude of the clinician arrive at a reasonably correct anatomical diagnosis. towards cyanotic congenital heart disease. It is At the same time knowledge of the natural history within the memory of many that it was the custom of congenital heart disease has also increased, and to make a simple diagnosis of congenital heart some idea of its prognosis has been ascertained. abnormality with cyanosis, and express the opinion Lastly, the conception of Taussig that an in- that little or nothing could be done about it. Then adequate pulmonary blood supply was the critical there appeared the pioneer work of Abbott and abnormality in many cyanotic cases, and the de- others which produced not only a classification of velopment of an anastomotic operation between the the various abnormalities, but furnished a mass of systemic and pulmonary circulations so as to clinical and postmortem observations from which furnish an artificial ductus arteriosus, by Blalock Protected by copyright. http://pmj.bmj.com/ on September 23, 2021 by guest. FIG. i.-Tetralogy of Fallot. Female aged 3 years. Right ventricle opened. An arrow marks the subvalvular stenosis. of the pulmonary artery. Ventricular septal defect with probe passing into it behind the crista supraventricularis.