How Computational Politics Harms Voter Privacy, and Proposed Regulatory Solutions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of Facebook Ads in European Election Campaigns

Are microtargeted campaign messages more negative and diverse? An analysis of Facebook ads in European election campaigns Alberto López Ortega University of Zurich Abstract Concerns about the use of online political microtargeting (OPM) by campaigners have arisen since Cambridge Analytica scandal hit the international political arena. In addition to providing conceptual clarity on OPM and explore the use of such technique in Europe, this paper seeks to empirically disentangle the differing behavior of campaigners when they message citizens through microtargeted rather than non-targeted campaigning. More precisely, I hypothesize that campaigners use negative campaigning and are more diverse in terms of topics when they use OPM. To investigate whether these expectations hold true, I use text-as-data techniques to analyze an original dataset of 4,091 political Facebook Ads during the last national elections in Austria, Italy, Germany and Sweden. Results show that while microtargeted ads might indeed be more thematically diverse, there does not seem to be a significant difference to non-microtargeted ads in terms of negativity. In conclusion, I discuss the implications of these findings for microtargeted campaigns and how future research could be conducted. Keywords: microtargeting, campaigns, negativity, topic diversity 1 1. Introduction In 2016, Alexander Nix, chief executive officer of Cambridge Analytica – a political consultancy firm – gave a presentation entitled “The Power of Big Data and Psychographics in the Electoral Process”. In his presentation, he explained how his firm allegedly turned Ted Cruz from being one of the less popular candidates in the Republican primaries to be the best competitor of Donald Trump. According to Nix’s words, they collected individuals’ personal data from a range of different sources, like land registries or online shopping data that allowed them to develop a psychographic profile of each citizen in the US. -

If It's Broke, Fix It: Restoring Federal Government Ethics and Rule Of

If it’s Broke, Fix it Restoring Federal Government Ethics and Rule of Law Edited by Norman Eisen The editor and authors of this report are deeply grateful to several indi- viduals who were indispensable in its research and production. Colby Galliher is a Project and Research Assistant in the Governance Studies program of the Brookings Institution. Maya Gros and Kate Tandberg both worked as Interns in the Governance Studies program at Brookings. All three of them conducted essential fact-checking and proofreading of the text, standardized the citations, and managed the report’s production by coordinating with the authors and editor. IF IT’S BROKE, FIX IT 1 Table of Contents Editor’s Note: A New Day Dawns ................................................................................. 3 By Norman Eisen Introduction ........................................................................................................ 7 President Trump’s Profiteering .................................................................................. 10 By Virginia Canter Conflicts of Interest ............................................................................................... 12 By Walter Shaub Mandatory Divestitures ...................................................................................... 12 Blind-Managed Accounts .................................................................................... 12 Notification of Divestitures .................................................................................. 13 Discretionary Trusts -

Cwa News-Fall 2016

2 Communications Workers of America / fall 2016 Hardworking Americans Deserve LABOR DAY: the Truth about Donald Trump CWA t may be hard ers on Trump’s Doral Miami project in Florida who There’s no question that Donald Trump would be to believe that weren’t paid; dishwashers at a Trump resort in Palm a disaster as president. I Labor Day Beach, Fla. who were denied time-and-a half for marks the tradi- overtime hours; and wait staff, bartenders, and oth- If we: tional beginning of er hourly workers at Trump properties in California Want American employers to treat the “real” election and New York who didn’t receive tips customers u their employees well, we shouldn’t season, given how earmarked for them or were refused break time. vote for someone who stiffs workers. long we’ve already been talking about His record on working people’s right to have a union Want American wages to go up, By CWA President Chris Shelton u the presidential and bargain a fair contract is just as bad. Trump says we shouldn’t vote for someone who campaign. But there couldn’t be a higher-stakes he “100%” supports right-to-work, which weakens repeatedly violates minimum wage election for American workers than this year’s workers’ right to bargain a contract. Workers at his laws and says U.S. wages are too presidential election between Hillary Clinton and hotel in Vegas have been fired, threatened, and high. Donald Trump. have seen their benefits slashed. He tells voters he opposes the Trans-Pacific Partnership – a very bad Want jobs to stay in this country, u On Labor Day, a day that honors working people trade deal for working people – but still manufac- we shouldn’t vote for someone who and kicks off the final election sprint to November, tures his clothing and product lines in Bangladesh, manufactures products overseas. -

Voters: Climate Change Is Real Threat; Want Path to Citizenship for Illegal Aliens; See Themselves As 2Nd Amendment Supporters; Divided on Obamacare & Fed Govt

SIENA RESEARCH INSTITUTE SIENA COLLEGE, LOUDONVILLE, NY www.siena.edu/sri For Immediate Release: Tuesday, September 27, 2016 Contact: Steven Greenberg (518) 469-9858 Crosstabs; website/Twitter: www.Siena.edu/SRI/SNY @SienaResearch Time Warner Cable News / Siena College 19th Congressional District Poll: Game On: Faso 43 Percent, Teachout 42 Percent ¾ of Dems with Teachout, ¾ of Reps with Faso; Inds Divided Voters: Climate Change Is Real Threat; Want Path to Citizenship for Illegal Aliens; See Themselves as 2nd Amendment Supporters; Divided on Obamacare & Fed Govt. Involvement in Economy Trump Leads Clinton by 5 Points; Schumer Over Long by 19 Points Loudonville, NY. The race to replace retiring Republican Representative Chris Gibson is neck and neck, as Republican John Faso has the support of 43 percent of likely voters and Democrat Zephyr Teachout has the support of 42 percent, with 15 percent still undecided, according to a new Time Warner Cable News/Siena College poll of likely 19th C.D. voters released today. Both have identical 75 percent support among voters from their party, with independents virtually evenly divided between the two. By large margins, voters say climate change is a real, significant threat; want a pathway to citizenship for aliens here illegally; and, consider themselves 2nd Amendment supporters rather than gun control supporters. Voters are closely divided on Obamacare, supporting its repeal by a small four-point margin, and whether the federal government should increase or lessen its role to stimulate the economy. In the race for President, Donald Trump has a 43-38 percent lead over Hillary Clinton, while Chuck Schumer has a 55-36 percent lead over Wendy Long in the race for United States Senator. -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Packaging Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3th639mx Author Galloway, Catherine Suzanne Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California PACKAGING POLITICS by Catherine Suzanne Galloway A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science in the Graduate Division of the University of California at Berkeley Committee in charge Professor Jack Citrin, Chair Professor Eric Schickler Professor Taeku Lee Professor Tom Goldstein Fall 2012 Abstract Packaging Politics by Catherine Suzanne Galloway Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science University of California, Berkeley Professor Jack Citrin, Chair The United States, with its early consumerist orientation, has a lengthy history of drawing on similar techniques to influence popular opinion about political issues and candidates as are used by businesses to market their wares to consumers. Packaging Politics looks at how the rise of consumer culture over the past 60 years has influenced presidential campaigning and political culture more broadly. Drawing on interviews with political consultants, political reporters, marketing experts and communications scholars, Packaging Politics explores the formal and informal ways that commercial marketing methods – specifically emotional and open source branding and micro and behavioral targeting – have migrated to the -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles The

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles The Effectiveness of Campaign Messages On Turnout and Vote Choice A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science by Sylvia Yu Friedel 2013 ©Copyright by Sylvia Yu Friedel 2013 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The Effectiveness of Campaign Messages On Turnout and Vote Choice by Sylvia Yu Friedel Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science University of California, Los Angeles, 2013 Professor Lynn Vavreck, Chair In this dissertation, I study campaign effects on turnout and vote choice. I analyze different campaign messages and the way they affect voters across various situations. First, through an online survey experiment, I study the impact of campaign messages and ideological cues on voters as they make inferences on candidates. Next, through a field experiment, I test whether microtargeted messages or general messages on the economy have any effect on turnout. Lastly, using online survey data, I examine how cross-pressured voters behave electorally when holding an opposing party’s position on social issues. These three studies indicate that different messages do, in fact, matter. Furthermore, voters are not fools—they are reasoning and rational. While partisanship does continue to heavily impact voting decisions, voters do consider issue positions and different voting dimensions (i.e., social, economic, moral). In light of this, campaigns should continue their efforts to persuade and inform the electorate. ii The dissertation -

Additional Submissions to Parliament in Support of Inquiries Regarding Brexit Damian Collins MP Dear Mr Collins, Over the Past M

Additional Submissions to Parliament in Support of Inquiries Regarding Brexit Damian Collins MP Dear Mr Collins, Over the past many months, I have been going through hundreds of thousands of emails and documents, and have come across a variety of communications that I believe are important in furthering your inquiry into what happened between Cambridge Analytica, UKIP and the Leave.EU campaign. As multiple enquiries found that no work was done, I would like to appeal those decisions with further evidence that should hopefully help you and your colleagues reach new conclusions. As you can see with the evidence outlined below and attached here, chargeable work was completed for UKIP and Leave.EU, and I have strong reasons to believe that those datasets and analysed data processed by Cambridge Analytica as part of a Phase 1 payable work engagement (see the proposal documents submitted last April), were later used by the Leave.EU campaign without Cambridge Analytica’s further assistance. The fact remains that chargeable work was done by Cambridge Analytica, at the direction of Leave.EU and UKIP executives, despite a contract never being signed. Despite having no signed contract, the invoice was still paid, not to Cambridge Analytica but instead paid by Arron Banks to UKIP directly. This payment was then not passed onto Cambridge Analytica for the work completed, as an internal decision in UKIP, as their party was not the beneficiary of the work, but Leave.EU was. I am submitting the following additional materials to supplement the testimony and documents I gave to the DCMS Committee last year as follows: 1) FW PRESS INVITATION HOW TO WIN THE EU REFERENDUM INVITE ONLY.pdf a. -

The Evolution of the Digital Political Advertising Network

PLATFORMS AND OUTSIDERS IN PARTY NETWORKS: THE EVOLUTION OF THE DIGITAL POLITICAL ADVERTISING NETWORK Bridget Barrett A thesis submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at the Hussman School of Journalism and Media. Chapel Hill 2020 Approved by: Daniel Kreiss Adam Saffer Adam Sheingate © 2020 Bridget Barrett ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Bridget Barrett: Platforms and Outsiders in Party Networks: The Evolution of the Digital Political Advertising Network (Under the direction of Daniel Kreiss) Scholars seldom examine the companies that campaigns hire to run digital advertising. This thesis presents the first network analysis of relationships between federal political committees (n = 2,077) and the companies they hired for electoral digital political advertising services (n = 1,034) across 13 years (2003–2016) and three election cycles (2008, 2012, and 2016). The network expanded from 333 nodes in 2008 to 2,202 nodes in 2016. In 2012 and 2016, Facebook and Google had the highest normalized betweenness centrality (.34 and .27 in 2012 and .55 and .24 in 2016 respectively). Given their positions in the network, Facebook and Google should be considered consequential members of party networks. Of advertising agencies hired in the 2016 electoral cycle, 23% had no declared political specialization and were hired disproportionately by non-incumbents. The thesis argues their motivations may not be as well-aligned with party goals as those of established political professionals. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES .................................................................................................................... V POLITICAL CONSULTING AND PARTY NETWORKS ............................................................................... -

Link to PDF Version

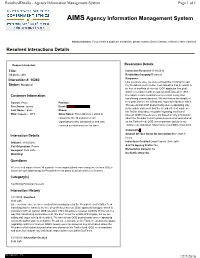

ResolvedDetails - Agency Information Management System Page 1 of 1 AIMS Agency Information Management System Announcement: If you create a duplicate interaction, please contact Gwen Cannon-Jenkins to have it deleted Resolved Interactions Details Reopen Interaction Resolution Details Title: Interaction Resolved:11/30/2016 34 press calls Resolution Category:Resolved Interaction #: 10260 Response: Like everyone else, we were excited this morning to read Status: Resolved the President-elect’s twitter feed indicating that he wants to be free of conflicts of interest. OGE applauds that goal, which is consistent with an opinion OGE issued in 1983. Customer Information Divestiture resolves conflicts of interest in a way that transferring control does not. We don’t know the details of Source: Press Position: their plan, but we are willing and eager to help them with it. The tweets that OGE posted today were responding only First Name: James Email: (b)(6) ' to the public statement that the President-elect made on Last Name: Lipton Phone: his Twitter feed about his plans regarding conflicts of Title: Reporter - NYT Other Notes: This contact is a stand-in interest. OGE’s tweets were not based on any information contact for the 34 separate news about the President-elect’s plans beyond what was shared organizations who contacted us and who on his Twitter feed. OGE is non-partisan and does not received our statement on the issue. endorse any individual. https://twitter.com/OfficeGovEthics Complexity( Amount Of Time Spent On Interaction:More than 8 Interaction Details hours Initiated: 11/30/2016 Individuals Credited:Leigh Francis, Seth Jaffe Call Origination: Phone Add To Agency Profile: No Assigned: Seth Jaffe Memorialize Content: No Watching: Do Not Destroy: No Questions We received inquires from 34 separate news organizations concerning tweets from OGE's twitter account addressing the President-elect's plans to avoid conflicts of interest. -

Cuomo's Progressive Promises, Reminiscent of Four Years Ago, Receiv

Cuomo's Progressive Promises, Reminiscent of Four Years Ago, Receiv... http://www.gothamgazette.com/state/7613-cuomo-s-2018-progressive-p... Cuomo's Progressive Promises, Reminiscent of Four Years Ago, Received Differently Sam Raskin Stewart-Cousins, Cuomo, and Klein at unity event (photo: Govenor's Office) In May 2014, Governor Andrew Cuomo attempted to earn the last-minute endorsement of The Working Families Party with a video address at its nominating convention. As Cuomo sought a second term that year, he made a series of promises demanded by WFP members and received the party’s backing and ballot line. The deal with frustrated progressive activists and labor union leaders, who make up the WFP, was in part brokered by Mayor Bill de Blasio after the WFP threatened to run Zephyr Teachout to Cuomo’s left. Cuomo, a Democrat, promised to back a series of progressive policies and a Democratic takeover of the state Senate -- including the reunification of mainline Democrats and the Independent Democratic Conference -- where he acknowledged that many of those policies had been blocked. Nearly four years later and with little he had promised the WFP accomplished, Cuomo made similar pronouncements, this time weeks ahead of the planned WFP convention, while he is facing a challenge from the left by actor and activist Cynthia 1 of 6 4/16/2018, 12:14 PM Cuomo's Progressive Promises, Reminiscent of Four Years Ago, Receiv... http://www.gothamgazette.com/state/7613-cuomo-s-2018-progressive-p... Nixon. Nixon won the endorsement of the WFP on Saturday, however, with the party losing union members loyal to Cuomo and being driven by activists disillusioned by the governor, though he has made attempts to win them over. -

Voter Privacy and Big-Data Elections

Osgoode Hall Law Journal Volume 58, Issue 1 (Winter 2021) Article 1 3-9-2021 Voter Privacy and Big-Data Elections Elizabeth F. Judge Centre for Law, Technology and Society, Faculty of Law, University of Ottawa Michael Pal Centre for Law, Technology and Society, Faculty of Law, University of Ottawa Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/ohlj Part of the Law Commons Article Citation Information Judge, Elizabeth F. and Pal, Michael. "Voter Privacy and Big-Data Elections." Osgoode Hall Law Journal 58.1 (2021) : 1-55. https://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/ohlj/vol58/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Osgoode Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Osgoode Hall Law Journal by an authorized editor of Osgoode Digital Commons. Voter Privacy and Big-Data Elections Abstract Big data and analytics have changed politics, with serious implications for the protection of personal privacy and for democracy. Political parties now hold large amounts of personal information about the individuals from whom they seek political contributions and, at election time, votes. This voter data is used for a variety of purposes, including voter contact and turnout, fundraising, honing of political messaging, and microtargeted communications designed specifically ot appeal to small subsets of voters. Yet both privacy laws and election laws in Canada have failed to keep up with these developments in political campaigning and are in need of reform to protect voter privacy. We provide an overview of big data campaign practices, analyze the gaps in Canadian federal privacy and election law that enable such practices, and offer recommendations to amend federal laws to address the threats to voter privacy posed by big data campaigns. -

Privacy and the Electorate

PRIVACY AND THE ELECTORATE Big Data and the Personalization of Politics Professor Elizabeth F. Judge & Professor Michael Pal* Faculty of Common Law, University of Ottawa Table of Contents Key Messages ................................................................................................................................. 3 Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................... 4 Context ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Implications ................................................................................................................................... 6 Results ............................................................................................................................................ 6 State of Knowledge ................................................................................................................................. 7 Regulatory Environment ....................................................................................................................... 7 Voter Databases and Voter Management Systems ............................................................................. 11 Self-Regulation ................................................................................................................................... 20 Voter Privacy Breaches ......................................................................................................................