Hoppe-Cruz Borja 2010 R.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Visual/Media Arts

A R T I S T D I R E C T O R Y ARTIST DIRECTORY (Updated as of August 2021) md The Guam Council on the Arts and Humanities Agency (GCAHA) has produced this Artist Directory as a resource for students, the community, and our constituents. This Directory contains names, contact numbers, email addresses, and mailing or home address of Artists on island and the various disciplines they represent. If you are interested in being included in the directory, please call our office at 300-1204~8/ 7583/ 7584, or visit our website (www.guamcaha.org) to download the Artist Directory Registration Form. TABLE OF CONTENTS DISCIPLINE PAGE NUMBER FOLK/ TRADITIONAL ARTS 03 - 17 VISUAL/ MEDIA ARTS 18 - 78 PERFORMING ARTS 79 - 89 LITERATURE/ HUMANITIES 90 - 96 ART RELATED ORGANIZATIONS 97 – 100 MASTER’S 101 - 103 2 FOLK/ TRADITIONAL ARTS Folk Arts enriches the lives of the Guam community, gives recognition to the indigenous and ethnic artists and their art forms and to promote a greater understanding of Guam’s native and multi-ethnic community. Ronald Acfalle “ Halu’u” P.O. BOX 9771 Tamuning, Guam 96931 [email protected] 671-689-8277 Builder and apprentice of ancient Chamorro (seafaring) sailing canoes, traditional homes and chanter. James Bamba P.O. BOX 26039 Barrigada, Guam 96921 [email protected] 671-488-5618 Traditional/ Contemporary CHamoru weaver specializing in akgak (pandanus) and laagan niyok (coconut) weaving. I can weave guagua’ che’op, ala, lottot, guaha, tuhong, guafak, higai, kostat tengguang, kustat mama’on, etc. Arisa Terlaje Barcinas P.O.BOX 864 Hagatna, Guam 96932 671-488-2782, 671-472-8896 [email protected] Coconut frond weaving in traditional and contemporary styles. -

Bus Schedule Carmel Catholic School Agat and Santa Rita Area to Mount Bus No.: B-39 Driver: Salas, Vincent R

BUS SchoolSCHEDULE Year 2020 - 2021 Dispatcher Bus Operations - 646-3122 | Superintendent Franklin F. Tait ano - 646-3208 | Assistant Superintendent Daniel B. Quintanilla - 647-5025 THE DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS, BUS OPERATIONS REQUIRES ALL STUDENTS TO WEAR A MASK PRIOR TO BOARDING THE BUS. THERE WILL BE ONE CHILD PER SEAT FOR SOCIAL DISTANCING. PLEASE ANTICIPATE DELAYS IN PICK UP AND DROP OFF AT DESIGNATED BUS SHELTERS. THANK YOU. TENJO VISTA AND SANTA RITA AREAS TO O/C-30 Hanks 5:46 2:29 OCEANVIEW MIDDLE SCHOOL O/C-29 Oceanview Drive 5:44 2:30 A-2 Tenjo Vista Entrance 7:30 4:01 O/C-28 Nimitz Hill Annex 5:40 2:33 A-3 Tenjo Vista Lower 7:31 4:00 SOUTHERN HIGH SCHOOL 6:15 1:50 AGAT A-5 Perez #1 7:35 3:56 PAGACHAO AREA TO MARCIAL SABLAN DRIVER: AGUON, DAVID F. A-14 Lizama Station 7:37 3:54 ELEMENTARY SCHOOL (A.M. ONLY) BUS NO.: B-123 A-15 Borja Station 7:38 3:53 SANTA ANA AREAS TO SOUTHERN HIGH SCHOOL A-38 Pagachao Upper 7:00 A-16 Naval Magazine 7:39 3:52 MARCIAL SABLAN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 7:10 STATION LOCATION NAME PICK UP DROP OFF A-17 Sgt. Cruz 7:40 3:51 A-44 Tracking Station Entrance 5:50 2:19 A-18 M & R Store 7:41 3:50 PAGACHAO AREA TO OCEANVIEW MIDDLE A-43 Cruz #2 5:52 2:17 SCHOOL A-42 San Nicolas 5:54 2:15 A-19 Annex 7:42 3:49 A-41 Quidachay 5:56 2:12 A-20 Rapolla Station 7:43 3:48 A-46 Round Table 7:15 3:45 A-40 Santa Ana 5:57 2:11 OCEANVIEW MIDDLE SCHOOL 7:50 3:30 A-38 Pagachao Upper 7:22 3:53 A-39 Last Stop 5:59 2:10 A-37 Pagachao Lower 7:25 3:50 SOUTHERN HIGH SCHOOL 6:11 1:50 HARRY S. -

Tournament Results 50 Oceania Circuit Events 52 Oceania Circuit Winners 53 Financial Accounts 54

ANNUAL REPORT 2011 Report & Financial Statements For Year Ending 31 December 2011 Front Cover Photograph 2011 Pacific Games Men‟s Singles Medalists Gold Medal Marc-Antoine Desaymoz (New Cal) Silver Medal Arnaud Franzi (New Cal) Bronze Medal William Jannic (New Cal) 2011 Annual Report www.oceaniabadminton.org Page 2 Content Page Officer Bearers 5 Committees 6 Presidents Report 7 Chief Operating Officers Report 9 Regional Development Officers Report 15 Committee Reports Technical Officials Committee 22 Women in Badminton 25 Events Committee 27 Players Advisory Group 30 Member Country Reports Australia 31 Tonga 36 Tuvalu 39 Tahiti 40 New Zealand 42 Guam 45 New Caledonia 46 Northern Marianas 4848 Tournament Results 50 Oceania Circuit Events 52 Oceania Circuit Winners 53 Financial Accounts 54 2011 Annual Report www.oceaniabadminton.org Page 3 2011 Annual Report www.oceaniabadminton.org Page 4 Office Bearers Executive Board Nigel Skelt New Zealand (President) Geraldine Brown Australia (Deputy President) Warren Yee Fiji Murray Weatherston New Zealand Loke Poh Wong Australia Karawa Areieta Kiribati Mathieu Dufermon New Caledonia Office Staff Corinne Barnard Chief Operating Officer Nadia Bleaken Regional Development Manager Bob Lindberg Bookkeeper Delegates Nigel Skelt BWF Vice President Geraldine Brown BWF Women in Badminton Committee Peter Cocker BWF Technical Officials Commission Rob Denton BWF Umpire Assessor Life Members Heather Robson 2011 Annual Report www.oceaniabadminton.org Page 5 Committees Technical Officials Peter Cocker (Australia) -

A Circular History of Modern Chamorro Activism

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Pomona Senior Theses Pomona Student Scholarship 2021 The Past as "Ahead": A Circular History of Modern Chamorro Activism Gabby Lupola Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/pomona_theses Part of the Asian American Studies Commons, Ethnic Studies Commons, Indigenous Studies Commons, Micronesian Studies Commons, Military History Commons, Oral History Commons, Political History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Lupola, Gabby, "The Past as "Ahead": A Circular History of Modern Chamorro Activism" (2021). Pomona Senior Theses. 246. https://scholarship.claremont.edu/pomona_theses/246 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Pomona Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pomona Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Past as “Ahead”: A Circular History of Modern Chamorro Activism Gabrielle Lynn Lupola A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in History at Pomona College. 23 April 2021 1 Table of Contents Images ………………………………………………………………….…………………2 Acknowledgments ……………………..……………………………………….…………3 Land Acknowledgment……………………………………….…………………………...5 Introduction: Conceptualizations of the Past …………………………….……………….7 Chapter 1: Embodied Sociopolitical Sovereignty on Pre-War Guam ……..……………22 -

Download This Volume

Photograph by Carim Yanoria Nåna by Kisha Borja-Quichocho Like the tåsa and haligi of the ancient Chamoru latte stone so, too, does your body maintain the shape of the healthy Chamoru woman. With those full-figured hips features delivered through natural birth for generations and with those powerful arms reaching for the past calling on our mañaina you have remained strong throughout the years continuously inspire me to live my culture allow me to grow into a young Chamoru woman myself. Through you I have witnessed the persistence and endurance of my ancestors who never failed in constructing a latte. I gima` taotao mo`na the house of the ancient people. Hågu i acho` latte-ku. You are my latte stone. The latte stone (acho` latte) was once the foundation of Chamoru homes in the Mariana Islands. It was carved out of limestone or basalt and varied in size, measuring between three and sixteen feet in height. It contained two parts, the tasa (a cup-like shape, the top portion of the latte) and the haligi (the bottom pillar) and were organized into two rows, with three to seven latte stones per row. Today, several latte stones still stand, and there are also many remnants of them throughout the Marianas. Though Chamorus no longer use latte stones as the foundations of their homes, the latte symbolize the strength of the Chamorus and their culture as well as their resiliency in times of change. Micronesian Educator Editor: Unaisi Nabobo-Baba Special Edition Guest Editors: Michael Lujan Bevacqua Victoria Lola Leon Guerrero Editorial Board: Donald Rubinstein Christopher Schreiner Editorial Assistants: Matthew Raymundo Carim Yanoria Design and Layout: Pascual Olivares ISSN 1061-088x Published by: The School of Education, University of Guam UOG Station, Mangilao, Guam 96923 Contents Guest Editor’s Introduction ............................................................................................................... -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions of Remarks E1470 HON

E1470 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks July 14, 2003 ANGEL ANTHONY LEON GUERRERO Guerrero Santos, III. Adios Angel. Si Yu’us erick (Fred) W. Rosen. Mr. Rosen was a SANTOS Ma’ase. Naval Officer, a businessman, a hometown f hero, and above all, a patriot. He was a friend to a President and national leaders and a wit- HON. MADELEINE Z. BORDALLO PERSONAL EXPLANATION OF GUAM ness to history. For his contributions to Dalton, Georgia and indeed the history of this great IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES HON. LORETTA SANCHEZ nation, I pay honor to him posthumously; Mr. Monday, July 14, 2003 OF CALIFORNIA Rosen died peacefully on July 14, 2003. Ms. BORDALLO. Mr. Speaker, I rise today IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Fred Rosen was born in 1917 in Brooklyn, New York, the son of Eastern European Jew- to pay tribute to former Guam Senator Angel Monday, July 14, 2003 Anthony Leon Guerrero Santos, III, a tireless ish immigrants. In the 1930s, as the Depres- champion of the rights of the Chamorro peo- Ms. LORETTA SANCHEZ of California. Mr. sion consumed the nation, Mr. Rosen’s broth- ple. Sadly, Angel passed away on July 6, Speaker, on Thursday, July 10, I was unavoid- er Ira moved to Dalton, Georgia seeking op- 2003 after suffering from a degenerative ill- ably detained due to a prior obligation in my portunity in the textile industry by opening the ness. district. La Rose Bedspread Company. Mr. Rosen was Angel was born on April 14, 1959 to Aman- I request that the CONGRESSIONAL RECORD a loyal Bulldog, attending the University of da Leon Guerrero Santos and Angel Cruz reflect that had I been present and voting, I Georgia and playing football there. -

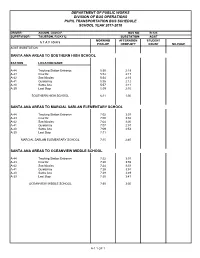

Department of Public Works Division of Bus Operations Pupil Transportation Bus Schedule School Year 2017-2018

DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS DIVISION OF BUS OPERATIONS PUPIL TRANSPORTATION BUS SCHEDULE SCHOOL YEAR 2017-2018 DRIVER: AGUON, DAVID F. BUS NO. B-123 SUPERVISOR: TAIJERON, RICKY U. SUBSTATION: AGAT MORNING AFTERNOON STUDENT S T A T I O N S PICK-UP DROP-OFF COUNT MILEAGE AGAT SUBSTATION SANTA ANA AREAS TO SOUTHERN HIGH SCHOOL STATION LOCATION NAME A-44 Tracking Station Entrance 5:50 2:19 A-43 Cruz #2 5:52 2:17 A-42 San Nicolas 5:54 2:15 A-41 Quidachay 5:56 2:12 A-40 Santa Ana 5:57 2:11 A-39 Last Stop 5:59 2:10 SOUTHERN HIGH SCHOOL 6:11 1:50 SANTA ANA AREAS TO MARCIAL SABLAN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL A-44 Tracking Station Entrance 7:02 3:03 A-43 Cruz #2 7:00 3:02 A-42 San Nicolas 7:04 3:00 A-41 Quidachay 7:07 2:57 A-40 Santa Ana 7:09 2:53 A-39 Last Stop 7:11 MARCIAL SABLAN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 7:15 2:40 SANTA ANA AREAS TO OCEANVIEW MIDDLE SCHOOL A-44 Tracking Station Entrance 7:22 3:57 A-43 Cruz #2 7:20 3:55 A-42 San Nicolas 7:24 3:53 A-41 Quidachay 7:26 3:51 A-40 Santa Ana 7:28 3:49 A-39 Last Stop 7:30 3:47 OCEANVIEW MIDDLE SCHOOL 7:35 3:30 A-1 1 OF 1 DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS DIVISION OF BUS OPERATIONS PUPIL TRANSPORTATION BUS SCHEDULE SCHOOL YEAR 2017-2018 DRIVER: BORJA, GARY P. -

Gender and the Person in Oceania

Gender and Person in Oceania October 1-2, 2011 Hedley Bull Lecture Theatre 2 Hedley Bull Building The Australian National University This workshop is a collaboration between the ARC Laureate project Engendering Persons, Transforming Things led by Professor Margaret Jolly and the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales-ANU Pacific Dialogues project led by Professor Serge Tcherkézoff. It brings together a range of early and mid-career researchers from across Australia working in Oceania with Professor Irène Théry from EHESS in France and researchers from New Caledonia. Presentations will address the following themes Contending notions of gender as an attribute of the person or a mode of sociality The co-presence and dialectical tensions between models of the person as ‗dividuals‘/relational persons versus individuals How best to understand the situation of transgendered persons in Oceania The influence of Christianities and commodity economics on gender and personhood Changing patterns of intimacy, domesticity and marriage Women‘s role in conflicts, peace and Christianities in the region The significance of mobility and new technologies of modernity Papers presented will traverse many countries: the Cook Islands, Fiji, French Polynesia, New Caledonia, Papua New Guinea, Samoa, Solomon Islands, and Vanuatu. The program is listed over. The emphasis will be on dialogue and debate: short papers of c. 15 minutes are paired in panels and discussion time will be long. This workshop is free and open to all but registration is required for catering purposes, by Friday September 23, by email to [email protected] Gender and Person in Oceania October 1-2, 2011 Hedley Bull Theatre 2, Hedley Bull Building ANU Campus Saturday October 1 10.00 – 10.30 Morning Tea 10.30 – 10.45 Welcome and Introduction Margaret Jolly 10.45 – 11.30 Opening Address Chaired by Serge Tcherkézoff „From the sociology of gender in Western countries towards an anthropology of gender in the Pacific .. -

Teachers Guide.Pages

I HINANAO-TA NU I MANAOTAO TÅNO’-I CHAMORU SIHA The Journey of the CHamoru People The Guam Museum’s Permanent Exhibition Teacher’s Guide Produced by Guampedia I HINANAO-TA NU I MANAOTAO TÅNO’-I CHAMORU SIHA The Journey of the CHamoru People The Guam Museum’s Permanent Exhibition Teacher’s Guide Note to readers: Underlined words in this document are links to entries in guampedia.com and other online resources. Guam Museum Permanent Exhibition Overview History of the Guam Museum The Guam Museum, officially called the Senator Antonio M. Palomo Guam and CHamoru Educational Facility, is the first structure built for the sole purpose of housing and displaying Guam’s precious historic treasures. The Guam Museum reflects the diversity, creativity, and resilience of the people of Guam and the Mariana Islands. The permanent exhibition is the story of the CHamoru people, told from a CHamoru perspective. It is hoped to encourage people to engage in dialogue, to share perspectives and experiences and debate issues that concern us all today. I Hale’ta: Mona yan Tatte: 90 Years in the Making The earliest printed record of people making plans for a new museum dates back to 1926. The Guam Teachers Association, led by Ramon M. Sablan, a teacher best known as the author of the “Guam Hymn,” asked residents and friends of Guam to start collecting their antiques and other artifacts for a museum that would protect their history and CHamoru culture. The editor of the Guam Recorder, one of the earliest publications printed and circulated on Guam, also called for the opening of a museum. -

Annual Report 2010

ANNUAL REPORT 2010 Front Cover Photographs (courtesy of) Roadshow in Guam Sandra Low Henry Tam & Donna Haliday (New Zealand) Southern Exposure Commonwealth Games Bronze Medalists Badminton Australia Kate Wilson-Smith/He Tian Tang (AUS) 2010 Annual Report www.oceaniabadminton.org Page 2 OFFICE BEARERS Executive Board Nigel Skelt New Zealand (President) Geraldine Brown Australia (Deputy President) Warren Yee Fiji Lynne Scutt New Zealand Loke Poh Wong Australia Toala Pule Risale Samoa Mathieu Dufermon New Caledonia Office Staff Corinne Barnard Chief Operating Officer Tony Mordaunt Regional Development Manager (left July 2010) Nadia Bleaken Regional Development Manager (started Sept 2010) Bob Lindberg Bookkeeper Delegates Nigel Skelt BWF Vice President Geraldine Brown BWF Women in Badminton Committee Peter Cocker BWF Technical Officials Commission Tania Luiz BWF Athletes Commission Life Members Heather Robson 2010 Annual Report www.oceaniabadminton.org Page 3 Committees Technical Officials Peter Cocker (Australia) (Chair) Yogen Bhatnagar (Australia) Lynne Nixey (New Zealand) Rob Denton (New Zealand) Events Ian Williamson (New Zealand) Julie Carrel (New Zealand) Kristine Thomas (Australia) Corinne Barnard (Oceania) Players Advisory Group Glenn Warfe (Australia) (Chair) Andra Whiteside (Fiji) Donna Haliday (New Zealand) Women in Badminton Geraldine Brown (Australia) (Chair) Violet Williams (Fiji) Denise Alexander (New Zealand) Ashleigh Marshall (Australia) Rhonda Cator (Australia) Corinne Barnard (Oceania) Nadia Bleaken (Oceania) International -

Andrew Reynolds - Women in the Legislatures and Executives of the Wo

Andrew Reynolds - Women in the Legislatures and Executives of the Wo... http://muse.jhu.edu.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/journals/world_politics/v... Copyright © 1999 by The Johns Hopkins University Press. All rights reserved. World Politics 51.4 (1999) 547-572 Andrew Reynolds * Tables Modern liberal democracy came into being in 1893, when New Zealand offered the franchise to women. The commonwealth state was the first to institutionally open up the public sphere to both men and women--a sphere that for hundreds, if not thousands, of years had been the monopoly of the patriarchal heads of family and business in almost every part of the globe. After a century of slow, incremental gains for women in politics, the results are mixed. Women are involving themselves in grassroots party structures in higher numbers than ever before. There are more women parliamentarians, 1 and increasingly cabinet portfolios are in the hands of women politicians. However, the numbers involved remain vastly disproportional to the importance women bring to societies, and in many parts of the world the representation of women remains little more than a blip on the male political landscape. This article reports the results of a survey of the governments of the world as they were constituted in 1998. The aim was threefold: (1) to map the number of women in legislative lower houses in 180 nation-states and related territories with autonomous governments; (2) to identify and categorize women in the executives of these 180 cases by type of ministerial portfolio; and (3) to test the leading hypotheses, which speculate about the factors hindering or facilitating women's access to political representation. -

Pacific Islands Women in the Eyes of the Travel Journalist Kanetaka Kaoru: Impressions from Her First Journey to the Pacific Islands in 1961

Pacific Islands Women in the Eyes of the Travel Journalist Kanetaka Kaoru: Impressions from Her First Journey to the Pacific Islands in 1961 Ryota Nishino The University of the South Pacific Abstract In 1961 a renowned Japanese travel journalist Kanetaka Kaoru (b. 1928) paid her first visit to the South Pacific Islands to film television travel documentary program Sekai no tabi (“The world around us”). Her travelogue that derived from the journey recounts how Kanetaka’s opinion of feminine beauty evolved from comments on beauty by appearance to astute queries of what beauty means. Her views, which sometimes challenged the conventional sociocultural mores of the Japan of her time, developed from her own descriptions of and interaction with women, and from the responses of tourists to her appearance. In Fiji she became increasingly aware that beauty is not only about appearance, but also about the whole decorum reflecting manners and morals. In Papua and New Guinea Kanetaka’s observation of and interaction with the women prompted questions about aesthetics, which branched off to considerations of what it means to be a human being. Situating Kanetaka’s Journey A woman clad in a kimono projects a confident smile. She spreads both arms at shoulder height displaying the draping sleeves of her kimono. In her left hand she holds a handbag bearing the Pan Am logo. Her eyes gaze out to the right, as if looking beyond the blank space toward future journeys. This is a photograph of Kanetaka Kaoru (b. 1928) taken at Haneda Airport in 1959, marking her inaugural filming trip for a program in a weekly television documentary Sekai no tabi (“The world around us”) (Kanetaka Watakushi 74–75).