A History of Voice Interaction in Digital Games

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kevin Koga CS465 9/5/08 Final Project Proposal (First Draft, First Idea)

Kevin Koga CS465 9/5/08 Final Project Proposal (First Draft, First Idea) Inspiration: The idea for my project was inspired by guitar hero. In guitar hero, players press buttons in time with a visual display of corresponding buttons and an audio track. Correctly pressing buttons scores you points, and you hear the guitar portion of the audio track. As someone who can actually read music, guitar hero always seemed too easy to me. Obviously the game is designed so that anyone can play it; even if they’ve never before seen written music. I was thinking about how Guitar Hero was eventually expanded to make Rock Band. I thought of how revolutionary those games have been. And my idea then occurred to me. Idea: When people learn to sight-sing music, the only feedback they have is their own ear. If you sing the wrong note, it sounds wrong. With the voice, there is no integral number of notes: no fingerings like on a trumpet, no frets like on a guitar. With voice, as with fretless string instruments such as violin or cello, you could be missing the note by only a quarter-step or less. To a trained ear, this makes a big difference. So I thought, why not add visual feedback? A microphone could be connected to a computer measuring frequency data in real time. The frequency or pitch of the note played or sung could move a cursor on the screen up or down. The cursor could sit atop musical staff, and point to the current note being played. -

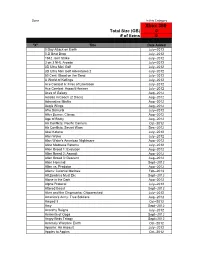

Xbox 360 Total Size (GB) 0 # of Items 0

Done In this Category Xbox 360 Total Size (GB) 0 # of items 0 "X" Title Date Added 0 Day Attack on Earth July--2012 0-D Beat Drop July--2012 1942 Joint Strike July--2012 3 on 3 NHL Arcade July--2012 3D Ultra Mini Golf July--2012 3D Ultra Mini Golf Adventures 2 July--2012 50 Cent: Blood on the Sand July--2012 A World of Keflings July--2012 Ace Combat 6: Fires of Liberation July--2012 Ace Combat: Assault Horizon July--2012 Aces of Galaxy Aug--2012 Adidas miCoach (2 Discs) Aug--2012 Adrenaline Misfits Aug--2012 Aegis Wings Aug--2012 Afro Samurai July--2012 After Burner: Climax Aug--2012 Age of Booty Aug--2012 Air Conflicts: Pacific Carriers Oct--2012 Air Conflicts: Secret Wars Dec--2012 Akai Katana July--2012 Alan Wake July--2012 Alan Wake's American Nightmare Aug--2012 Alice Madness Returns July--2012 Alien Breed 1: Evolution Aug--2012 Alien Breed 2: Assault Aug--2012 Alien Breed 3: Descent Aug--2012 Alien Hominid Sept--2012 Alien vs. Predator Aug--2012 Aliens: Colonial Marines Feb--2013 All Zombies Must Die Sept--2012 Alone in the Dark Aug--2012 Alpha Protocol July--2012 Altered Beast Sept--2012 Alvin and the Chipmunks: Chipwrecked July--2012 America's Army: True Soldiers Aug--2012 Amped 3 Oct--2012 Amy Sept--2012 Anarchy Reigns July--2012 Ancients of Ooga Sept--2012 Angry Birds Trilogy Sept--2012 Anomaly Warzone Earth Oct--2012 Apache: Air Assault July--2012 Apples to Apples Oct--2012 Aqua Oct--2012 Arcana Heart 3 July--2012 Arcania Gothica July--2012 Are You Smarter that a 5th Grader July--2012 Arkadian Warriors Oct--2012 Arkanoid Live -

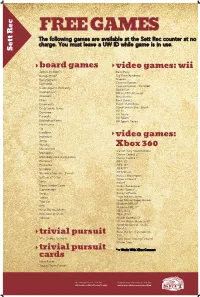

Sett Rec Counter at No Charge

FREE GAMES The following games are available at the Sett Rec counter at no charge. You must leave a UW ID while game is in use. Sett Rec board games video games: wii Apples to Apples Bash Party Backgammon Big Brain Academy Bananagrams Degree Buzzword Carnival Games Carnival Games - MiniGolf Cards Against Humanity Mario Kart Catchphrase MX vs ATV Untamed Checkers Ninja Reflex Chess Rock Band 2 Cineplexity Super Mario Bros. Crazy Snake Game Super Smash Bros. Brawl Wii Fit Dominoes Wii Music Eurorails Wii Sports Exploding Kittens Wii Sports Resort Finish Lines Go Headbanz Imperium video games: Jenga Malarky Mastermind Xbox 360 Call of Duty: World at War Monopoly Dance Central 2* Monopoly Deal (card game) Dance Central 3* Pictionary FIFA 15* Po-Ke-No FIFA 16* Scrabble FIFA 17* Scramble Squares - Parrots FIFA Street Forza 2 Motorsport Settlers of Catan Gears of War 2 Sorry Halo 4 Super Jumbo Cards Kinect Adventures* Superfection Kinect Sports* Swap Kung Fu Panda Taboo Lego Indiana Jones Toss Up Lego Marvel Super Heroes Madden NFL 09 Uno Madden NFL 17* What Do You Meme NBA 2K13 Win, Lose or Draw NBA 2K16* Yahtzee NCAA Football 09 NCAA March Madness 07 Need for Speed - Rivals Portal 2 Ruse the Art of Deception trivial pursuit SSX 90's, Genus, Genus 5 Tony Hawk Proving Ground Winter Stars* trivial pursuit * = Works With XBox Connect cards Harry Potter Young Players Edition Upcoming Events in The Sett Program your own event at The Sett union.wisc.edu/sett-events.aspx union.wisc.edu/eventservices.htm. -

Dance Central 2

wygenerowano 28/09/2021 10:36 Dance Central 2 cena 49 zł dostępność Oczekujemy platforma Xbox 360 odnośnik robson.pl/produkt,13484,dance_central_2.html Adres ul.Powstańców Śląskich 106D/200 01-466 Warszawa Godziny otwarcia poniedziałek-piątek w godz. 9-17 sobota w godz. 10-15 Nr konta 25 1140 2004 0000 3702 4553 9550 Adres e-mail Oferta sklepu : [email protected] Pytania techniczne : [email protected] Nr telefonów tel. 224096600 Serwis : [email protected] tel. 224361966 Zamówienia : [email protected] Wymiana gier : [email protected] Dance Central 2 jest kontynuacją sławnej gry muzycznej, która ukazała się na Xboxa 360 w 2010 roku. Za produkcję odpowiada studio Harmonix Music Systems, które jest znane m.in. z Green Day: Rock Band oraz Guitar Hero II. Rozgrywka w Dance Central 2 ponownie polega na odpowiednim wykonywaniu ruchów w rytm muzyki. W grze znajdziemy ponad czterdzieści nowych piosenek, a posiadacze wcześniejszej odsłony cyklu mogą przenieść wszystkie utwory z pierwowzoru (niestety, konieczne jest uiszczenie dodatkowej opłaty). W Dance Central 2 usprawniono tryb Break It Down i ulepszono tryb wieloosobowy (teraz dwóch graczy może bawić się jednocześnie). Pełna lista utworów: Level 1 1. Sandstorm – Darude 2. Mai Ai Hee (Dragostea Din Tea) – O-Zone 3. Reach – Atlantic Connection And Armanni Reign 4. Real Love – Mary J. Blige Level 2 1. Venus – Bananarama 2. Bulletproof – La Roux 3. Turn Me On – Kevin Lyttle 4. Last Night – P. Diddy feat. Keyshia Cole 5. The Humpty Dance – Digital Underground 6. Impacto (Remix) – Daddy Yankee feat. Fergie 7. This Is How We Do It – Montell Jordan 8. The Breaks – Kurtis Blow Level 3 1. -

Thebestway FIFA 14 | GOOGLE GLASS | PS4 | DEAD MOUSE + MORE

THE LAUNCH ISSUE T.O.W.I.E TO MK ONLY THE BEST WE LET MARK WRIGHT WE TRAVEL TO CHELSEA AND JAMESIII.V. ARGENT MMXIIIAND TALK BUSINESS LOOSE IN MILTON KEYNES WITH REFORMED PLAYBOY CALUM BEST BAG THAT JOB THE ESSENTIAL GUIDE TO HOT HATCH WALKING AWAY WITH WE GET HOT AND EXCITED THE JOB OFFER OVER THE LATEST HATCHES RELEASED THIS SUMMER LOOKING HOT GET THE STUNNING LOOKS ONE TOO MANY OF CARA DEVEVINGNE DO YOU KNOW WHEN IN FIVE SIMPLE STEPS ENOUGH IS ENOUGH? THEBESTway FIFA 14 | GOOGLE GLASS | PS4 | DEAD MOUSE + MORE CONTENTS DOING IT THE WRIGHT WAY - THE TRENDLIFE LAUNCH PARTY The Only Way To launch TrendLife Magazine saw Essex boys Mark Wright and James ‘Arg’ Argent join us at Wonderworld in Milton Keynes alongside others including Corrie’s Michelle Keegen. Take a butchers at page 59 me old china. 14 MAIN FEATURES CALUM BEST ON CALUM BEST We sit down with Calum Best at 7 - 9 Chelsea’s Broadway House to discuss his new look on life, business and of course, the ladies. 12 MUST HAVES FOR SUMMER Get your credit card at the ready as 12 we give you ‘His and Hers’ essentials for this summer. You can thank us later. NEVER MIND THE SMALLCOCK Ladies, you have all been there and if 18 you have not, you will. What do you do when you are confronted with the ultimate let down? Fight or flight? #TRENDLIFEAWARDS REGISTER TODAY FOR THE EVENT OF 2013 WHATS NEW FIFA 14 PREVIEW | 35 No official release date. -

From an Ethnic Island to a Transnational Bubble: a Reflection on Korean Americans in Los Angeles

Asian and Asian American Studies Faculty Works Asian and Asian American Studies 2012 From an Ethnic Island to a Transnational Bubble: A Reflection on Korean Americans in Los Angeles Edward J.W. Park Loyola Marymount University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/aaas_fac Part of the East Asian Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Edward J.W. Park (2012) From an Ethnic Island to a Transnational Bubble: A Reflection on orK ean Americans in Los Angeles, Amerasia Journal, 38:1, 43-47. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Asian and Asian American Studies at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Asian and Asian American Studies Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. From an Ethnic Island to a Transnational Bubble Transnational a to Island an Ethnic From So much more could be said in reflecting on Sa-I-Gu. My main goal in this brief essay has simply been to limn the ways in which the devastating fires of Sa-I-Gu have produced a loamy and fecund soil for personal discovery, community organizing, political mobilization, and, ultimately, a remaking of what it means to be Korean and Asian in the United States. From an Ethnic Island to a Transnational Bubble: A Reflection on Korean Americans in Los Angeles Edward J.W. Park EDWARD J.W. PARK is director and professor of Asian Pacific American Studies at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles. -

Towards Collection Interfaces for Digital Game Objects

“The Collecting Itself Feels Good”: Towards Collection Interfaces for Digital Game Objects Zachary O. Toups,1 Nicole K. Crenshaw,2 Rina R. Wehbe,3 Gustavo F. Tondello,3 Lennart E. Nacke3 1Play & Interactive Experiences for Learning Lab, Dept. Computer Science, New Mexico State University 2Donald Bren School of Information and Computer Sciences, University of California, Irvine 3HCI Games Group, Games Institute, University of Waterloo [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Figure 1. Sample favorite digital game objects collected by respondents, one for each code from the developed coding manual (except MISCELLANEOUS). While we did not collect media from participants, we identified representative images0 for some responses. From left to right: CHARACTER: characters from Suikoden II [G14], collected by P153; CRITTER: P32 reports collecting Arnabus the Fairy Rabbit from Dota 2 [G19]; GEAR: P55 favorited the Gjallerhorn rocket launcher from Destiny [G10]; INFORMATION: P44 reports Dragon Age: Inquisition [G5] codex cards; SKIN: P66’s favorite object is the Cauldron of Xahryx skin for Dota 2 [G19]; VEHICLE: a Jansen Carbon X12 car from Burnout Paradise [G11] from P53; RARE: a Hearthstone [G8] gold card from the Druid deck [P23]; COLLECTIBLE: World of Warcraft [G6] mount collection interface [P7, P65, P80, P105, P164, P185, P206]. ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION Digital games offer a variety of collectible objects. We inves- People collect objects for many reasons, such as filling a per- tigate players’ collecting behaviors in digital games to deter- sonal void, striving for a sense of completion, or creating a mine what digital game objects players enjoyed collecting and sense of order [8,22,29,34]. -

PLAYSTATION XBOX a Plague Tale: Innocence CZ a Plague Tale: Innocence CZ A.O.T

PLAYSTATION XBOX A Plague Tale: Innocence CZ A Plague Tale: Innocence CZ A.o.T. 2 AO Tennis 2 A.o.T.: Wings of Freedom Assassin’s Creed: Odyssey CZ Assassin’s Creed: Odyssey CZ Assassin’s Creed: Valhalla Assassin’s Creed: Valhalla Call of Duty Black Ops: Cold War Blue Reflection Call of Duty: Modern Warfare Bus Simulator Conan Exiles (Day One Edition) Cabela’s African Adventures Crash Bandicoot 4: It’s About Time Call of Duty Black Ops: Cold War Crash Bandicoot N.Sane Trilogy Call of Duty: Modern Warfare Desperados 3 Crash Bandicoot 4: It’s About Time DiRT 5 Crash Bandicoot N.Sane Trilogy Disney Infinity 2.0: Marvel Super Heroes (Starter Pack) Crash Team Racing + Crash Bandicoot N.Sane Bundle DOOM Eternal Danganronpa 1&2 Reload Dragon Ball Z: Kakarot Dark Souls Trilogy EA Sports UFC 4 Dead Island CZ (Definitive Collection) F1 2020: The Official Videogame (Seventy Edition) Desperados 3 Far Cry: Primal CZ (Collector’s Edition) DiRT 5 Farming Simulator 19 Disney Infinity 2.0: Marvel Super Heroes (Starter Pack) Farming Simulator 19 CZ (Platinum Edition) Divinity: Original Sin (Enhanced Edition) FIFA 21 CZ Dragon Ball Z: Kakarot Forza Horizon 4 Dragon Quest 11: Echoes of an Elusive Age Guitar Hero Live + gitara EA Sports UFC 4 Hunting Simulator F1 2020: The Official Videogame (Seventy Edition) Hunting Simulator 2 Fairy Tail Jumanji: The Video Game Far Cry 4 + Far Cry: Primal CZ (Double Pack) Jurassic World Evolution Farming Simulator 19 Just Dance 2020 Farming Simulator 19 CZ (Platinum Edition) Kinect Sports Rivals CZ FIFA 21 CZ Madden NFL -

Access All Areas? the Evolution of Singstar from the PS2 to PS3 Platform

This may be the author’s version of a work that was submitted/accepted for publication in the following source: Fletcher, Gordon, Light, Ben, & Ferneley, Elaine (2008) Access all areas? The evolution of SingStar from the PS2 to PS3 platform. In Loader, B (Ed.) Internet Research 9.0: Rethinking Community, Rethink- ing Space (2008) - 9th Annual Conference of the Association of Internet Researchers. Association of Internet Researchers, Denmark, pp. 1-13. This file was downloaded from: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/75684/ c Copyright 2008 the authors This work is covered by copyright. Unless the document is being made available under a Creative Commons Licence, you must assume that re-use is limited to personal use and that permission from the copyright owner must be obtained for all other uses. If the docu- ment is available under a Creative Commons License (or other specified license) then refer to the Licence for details of permitted re-use. It is a condition of access that users recog- nise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. If you believe that this work infringes copyright please provide details by email to [email protected] Notice: Please note that this document may not be the Version of Record (i.e. published version) of the work. Author manuscript versions (as Sub- mitted for peer review or as Accepted for publication after peer review) can be identified by an absence of publisher branding and/or typeset appear- ance. If there is any doubt, please refer to the published source. Access All Areas? The -

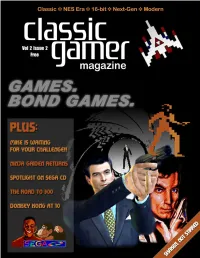

Cgm V2n2.Pdf

Volume 2, Issue 2 July 2004 Table of Contents 8 24 Reset 4 Communist Letters From Space 5 News Roundup 7 Below the Radar 8 The Road to 300 9 Homebrew Reviews 11 13 MAMEusements: Penguin Kun Wars 12 26 Just for QIX: Double Dragon 13 Professor NES 15 Classic Sports Report 16 Classic Advertisement: Agent USA 18 Classic Advertisement: Metal Gear 19 Welcome to the Next Level 20 Donkey Kong Game Boy: Ten Years Later 21 Bitsmack 21 Classic Import: Pulseman 22 21 34 Music Reviews: Sonic Boom & Smashing Live 23 On the Road to Pinball Pete’s 24 Feature: Games. Bond Games. 26 Spy Games 32 Classic Advertisement: Mafat Conspiracy 35 Ninja Gaiden for Xbox Review 36 Two Screens Are Better Than One? 38 Wario Ware, Inc. for GameCube Review 39 23 43 Karaoke Revolution for PS2 Review 41 Age of Mythology for PC Review 43 “An Inside Joke” 44 Deep Thaw: “Moortified” 46 46 Volume 2, Issue 2 July 2004 Editor-in-Chief Chris Cavanaugh [email protected] Managing Editors Scott Marriott [email protected] here were two times a year a kid could always tures a firsthand account of a meeting held at look forward to: Christmas and the last day of an arcade in Ann Arbor, Michigan and the Skyler Miller school. If you played video games, these days writer's initial apprehension of attending. [email protected] T held special significance since you could usu- Also in this issue you may notice our arti- ally count on getting new games for Christmas, cles take a slight shift to the right in the gaming Writers and Contributors while the last day of school meant three uninter- timeline. -

Game Design Concepts

Game Design Concepts: An experiment in game design and teaching Ian Schreiber Syllabus and Schedule 3 Level 1: Overview / What is a Game? 6 Level 2: Game Design / Iteration and Rapid Prototyping 15 Level 3: Formal Elements of Games 21 Level 4: The Early Stages of the Design Process 33 Level 5: Mechanics and Dynamics 47 Level 6: Games and Art 61 Level 7: Decision-Making and Flow Theory 73 Level 8: Kinds of Fun, Kinds of Players 86 Level 9: Stories and Games 97 Level 10: Nonlinear Storytelling 109 Level 11: Design Project Overview 121 Level 12: Solo Testing 127 Level 13: Playing With Designers 134 Level 14: Playing with Non-Designers 139 Level 15: Blindtesting 144 Level 16: Game Balance 149 Level 17: User Interfaces 160 Level 18: The Final Iteration 168 Level 19: Game Criticism and Analysis 174 Level 20: Course Summary and Next Steps 177 Syllabus and Schedule By ai864 Schedule: This class runs from Monday, June 29 through Sunday, September 6. Posts appear on the blog Mondays and Thursdays each week at noon GMT. Discussions and sharing of ideas happen on a continual basis. Textbooks: This course has one required text, and two recommended texts that will be referenced in several places and provide good “next steps” after the summer course ends. Required Text: Challenges for Game Designers, by Brathwaite & Schreiber. This book covers a lot of basic information on both practical and theoretical game design, and we will be using it heavily, supplemented with some readings from other online sources. Yes, I am one of the authors. -

Outer Worlds Strategy Guide

Outer worlds strategy guide Continue This tips and strategy section for playing The Outside Worlds. Check out this page for a list of tips and strategies available to win the game. In this list, we hope to provide the player with essentials to not only survive Halcyon, but effectively moves his dangers and win the game! Read on and find out if there is an important thing missing or something that is needed to conquer the problems of the Outer Worlds! Check out our Mechanics section of the game and also learn all all and outs about how the game works. Game Mechanics As you play through the game, you will develop your character according to your specific style of play. Learn how to develop your character and mates and all the different potential ways you can knock your enemies six ways from Sunday! The best starting build and early game builds the best character builds the best build for each companion Best Perks Best attributes Best ability to choose the best and worst flaws How to increase attributes How to reset perks where you are a Halcyon hero or vigilante on the go, you need to know the ropes to keep your own there. Our guides will teach you how to master every aspect of gameplay! What you need to know before you play the game is how to get bits quickly, how to get Exp Fast Best side quests to complete the best consumables to use where to sell junk (en) What to do with junk Where to buy items (en) Buying a guide to weapons, armor, fashion..