Representative Identity and Policy Outcomes for Equity-Seeking Groups

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nancy Marshau- Ward 22 Library Cuts To: Date: Subject: John Warren

Page 1oft Nancy MarshaU- Ward 22 Library Cuts From: John Warren <[email protected]> To: <nmarshall@torontopubliclibrary .ca> Date: October 18, 2011 9:40PM Subject: Ward 22 Library Cuts Dear Ms. Marshall, I am a frequent user of The Deer Park Branch and there is no reason that I can see that it is underutilized at any time during the day and week. The adults are the prime users and the computers all always busy, the media area it is hard to find a chair most times, there are people amongst the stacks and DVD shelves. I am a writer, amongst other things, and order many books that I pick up there. There are many more reasons that I could mention but I think you get my point that these cuts are not investigated adequately and rationally thought out I see that 39 branches will be up for cuts and interestingly, so I read, many are in the poorer areas and the most busy! This is FORD's logical ill-logic. Thank you for hearing my feedback. Good luck and Best Regards, John Warren #22 - 494 Avenue Rd M4V2J5 file://C:\Documents and Settings\nmarshall\Local Settings\Temp\XPgrpwise\4E9DF233... 21110/2011 Proposed Ltbrary reducttons ~LtPage I of! Nancy MarshaU- Proposed Library reductions From: Iori harrison <[email protected]> To: <[email protected]> Date: October 18,2011 9:51PM Subject: Proposed Library reductions Hello, I would like to voice my concerns about cutting library times. libraries are a fundamental core service for our communities that service young people, new Canadians, the elder1y and everyone in between. -

A Community Benefits Policy Framework for Ontario

Boldly Progressive, Fiscally Balanced: A Community Benefits Policy Framework for Ontario Community Benefits Ontario March 2017 March 13, 2017 Who We Are This Community Benefits Framework for Ontario was developed collaBoratively through participants in the Community Benefits Ontario network, a Broad network of Ontario nonprofits, foundations, labour groups, community organizations, municipal representatives and social enterprise leaders. This brief is brought forward by the following: Colette Murphy, Executive Director, Atkinson Foundation Anne Gloger, Principal, East Scarborough Storefront Terry Cooke, President & CEO, Hamilton Community Foundation Howard Elliott, Chair, Hamilton RoundtaBle for Poverty Reduction Marc Arsenault, Stakeholder Relations, Ironworkers District Council of Ontario Mustafa ABdi, Community Organizer, Communities Organizing for ResponsiBle Development, LaBour Community Services Elizabeth McIsaac, President, Maytree Sandy Houston, President and CEO, Metcalf Foundation Cathy Taylor, Executive Director, Ontario Nonprofit Network John Cartwright, President, Toronto & York Region LaBour Council Rosemarie Powell, Executive Director, Toronto Community Benefits Network Anne Jamieson, Senior Manager, Toronto Enterprise Fund Anita Stellinga, Interim CEO, United Way of Peel Region Lorraine Goddard, CEO, United Way/Centraide Windsor-Essex County Daniele Zanotti, President and CEO, United Way Toronto & York Region 1 March 13, 2017 “Infrastructure projects such as the Eglinton Crosstown LRT can create benefits for communities that go beyond simply building the infrastructure needed. Through this agreement, people facing employment challenges will have the opportunity to acquire new skills and get good joBs in construction. We’re Building more than transit. We’re Building partnerships and pathways that are creating more opportunities for people to thrive in the economy.” - Premier Kathleen Wynne 1 December 7, 2016 Premier Wynne greets contractors and construction workers at the ground breaking of the first Eglinton Crosstown station. -

Authority Meeting #4/16 Was Held at TRCA Head Office, on Friday, May 27, 2016

Authority Meeting #4/16 was held at TRCA Head Office, on Friday, May 27, 2016. The Chair Maria Augimeri, called the meeting to order at 9:32 a.m. PRESENT Kevin Ashe Member Maria Augimeri Chair Jack Ballinger Member Ronald Chopowick Member Vincent Crisanti Member Glenn De Baeremaeker Member Michael Di Biase Vice Chair Jennifer Drake Member Chris Fonseca Member Jack Heath Member Jennifer Innis Member Colleen Jordan Member Matt Mahoney Member Giorgio Mammoliti Member Glenn Mason Member Mike Mattos Member Frances Nunziata Member Linda Pabst Member Anthony Perruzza Member Gino Rosati Member John Sprovieri Member Jim Tovey Member ABSENT Paul Ainslie Member David Barrow Member Justin Di Ciano Member Maria Kelleher Member Jennifer McKelvie Member Ron Moeser Member RES.#A55/16 - MINUTES Moved by: Chris Fonseca Seconded by: Kevin Ashe THAT the Minutes of Meeting #3/16, held on April 22, 2016, be received. CARRIED ______________________________ CITY OF TORONTO REPRESENTATIVE ON THE BUDGET/AUDIT ADVISORY BOARD Ronald Chopowick was nominated by Jack Heath. 110 RES.#A56/16 - MOTION TO CLOSE NOMINATIONS Moved by: Linda Pabst Seconded by: Glenn De Baeremaeker THAT nominations for the City of Toronto representative on the Budget/Audit Advisory Board be closed. CARRIED Ronald Chopowick was declared elected by acclamation as the City of Toronto representative on the Budget/Audit Advisory Board, for a term to end at Annual Meeting #1/17. ______________________________ DELEGATIONS 5.1 A delegation by Martin Medeiros, Regional Councillor, City of Brampton, in regard to item 8.3 - Hurontario-Main Street Light Rail Transit (LRT). 5.2 A delegation by Andrew deGroot, One Brampton, in regard to item 8.3 - Hurontario-Main Street Light Rail Transit (LRT). -

“Mr. Ford Risks Alienating His Key Supporters: Both the Business Community and Fellow Conservatives

Queen’s Park Today – Daily Report November 2, 2020 Quotation of the day “Mr. Ford risks alienating his key supporters: both the business community and fellow conservatives. And Mr. Kenney, experts warn, could quickly set off a public-health disaster if the situation gets out of control.” The Globe and Mail compares Ontario and Alberta's pandemic responses. While Premier Jason Kenney has been criticized for a lighter-touch approach, Premier Doug Ford may be pivoting to Kenney's playbook, asking health officials to draft a plan to ease restrictions in hot spots. Today at Queen’s Park Written by Sabrina Nanji On the schedule The house reconvenes at 9 a.m. for private members’ business; on this morning's docket is second reading of NDP MPP Jeff Burch's Bill 164, Protecting Vulnerable Persons in Supportive Living Accommodation Act. Burch's bill would establish a licensing system for operators of supportive living settings such as nursing homes and children's residences. Bill 202, Soldiers' Aid Commission Act — which shakes up the commission's operations and reporting requirements — was referred back to the house from committee last week and is expected to be called for third reading this afternoon. With a handful of government bills currently at the committee stage, Bill 213 and Bill 207 are the only other ones that could be up for debate today. Bill 213, at second reading, is the red-tape reduction legislation that also gives degree-granting powers and university status to Charles McVety's Canada Christian College. Bill 207 is now back from committee study and poised for third reading; it would align provincial family law with recent federal changes. -

Summary by Quartile.Xlsx

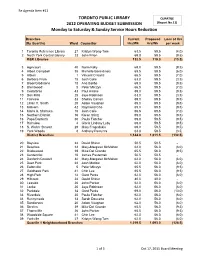

Re Agenda Item #11 TORONTO PUBLIC LIBRARY QUARTILE 2012 OPERATING BUDGET SUBMISSION (Report No.11) Monday to Saturday & Sunday Service Hours Reduction Branches Current Proposed Loss of Hrs (By Quartile) Ward Councillor Hrs/Wk Hrs/Wk per week 1 Toronto Reference Library 27 Kristyn Wong-Tam 63.5 59.5 (4.0) 2 North York Central Library 23 John Filion 69.0 59.5 (9.5) R&R Libraries 132.5 119.0 (13.5) 3 Agincourt 40 Norm Kelly 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 4 Albert Campbell 35 Michelle Berardinetti 65.5 59.5 (6.0) 5 Albion 1 Vincent Crisanti 66.5 59.5 (7.0) 6 Barbara Frum 15 Josh Colle 63.0 59.5 (3.5) 7 Bloor/Gladstone 18 Ana Bailão 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 8 Brentwood 5 Peter Milczyn 66.5 59.5 (7.0) 9 Cedarbrae 43 Paul Ainslie 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 10 Don Mills 25 Jaye Robinson 63.0 59.5 (3.5) 11 Fairview 33 Shelley Carroll 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 12 Lillian H. Smith 20 Adam Vaughan 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 13 Malvern 42 Raymond Cho 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 14 Maria A. Shchuka 15 Josh Colle 66.5 59.5 (7.0) 15 Northern District 16 Karen Stintz 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 16 Pape/Danforth 30 Paula Fletcher 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 17 Richview 4 Gloria Lindsay Luby 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 18 S. Walter Stewart 29 Mary Fragedakis 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 19 York Woods 8 AAnthonynthony Perruzza 63.0 59.5 ((3.5)3.5) District Branches 1,144.0 1,011.5 (132.5) 20 Bayview 24 David Shiner 50.5 50.5 - 21 Beaches 32 Mary-Margaret McMahon 62.0 56.0 (6.0) 22 Bridlewood 39 Mike Del Grande 65.5 56.0 (9.5) 23 Centennial 10 James Pasternak 50.5 50.5 - 24 Danforth/Coxwell 32 Mary-Margaret McMahon 62.0 56.0 (6.0) 25 Deer Park 22 Josh Matlow 62.0 56.0 (6.0) -

While Every Effort Is Made to Ensure the Accuracy of the Contents

While every effort is made to ensure the accuracy of the contents of this site, users should be aware that due to circumstances beyond our control, it may be necessary to change the text of documents posted here and therefore no responsibility will be accepted by the Toronto Transit Commission for discrepancies which may occur between documents contained on this site and the formal hardcopy versions presented to the Commission. If it is necessary to rely on the accuracy of Commission documents the Office of the General Secretary should be contacted at 393-3698 to obtain a certifed copy. ONLY HARDCOPY RECORDS CERTIFIED BY THE GENERAL SECRETARY WILL BE DEEMED TO BE OFFICIAL. Form Revised: February 2005 TORONTO TRANSIT COMMISSION REPORT NO. MEETING DATE: March 21, 2007 SUBJECT: Membership – TTC Committees RECOMMENDATION It is recommended that the Commission receive this report for information. DISCUSSION The attached provides a list of TTC Committees along with the membership for each Committee. - - - - - - - - - - - - March 2, 2007 1-16 Attachment TTC COMMITTEES TTC PROPERTY COMMITTEE Michael Thompson (Chair) Glenn De Baeremaeker Adam Giambrone Suzan Hall Peter Milczyn Anthony Perruzza TTC ADVERTISING REVIEW COMMITTEE Sandra Bussin Suzan Hall Anthony Perruzza Bill Saundercook (Committee Chair to be determined) TTC AUDIT COMMITTEE Bill Saundercook (Chair) Adam Giambrone Anthony Perruzza TTC BUDGET COMMITTEE Adam Giambrone Joe Mihevc Peter Milczyn Anthony Perruzza Bill Saundercook Michael Thompson (Committee Chair to be determined) TTC e-SYSTEM -

Agenda Item History - 2013.MM41.25

Agenda Item History - 2013.MM41.25 http://app.toronto.ca/tmmis/viewAgendaItemHistory.do?item=2013.MM... Item Tracking Status City Council adopted this item on November 13, 2013 with amendments. City Council consideration on November 13, 2013 MM41.25 ACTION Amended Ward:All Requesting Mayor Ford to respond to recent events - by Councillor Denzil Minnan-Wong, seconded by Councillor Peter Milczyn City Council Decision Caution: This is a preliminary decision. This decision should not be considered final until the meeting is complete and the City Clerk has confirmed the decisions for this meeting. City Council on November 13 and 14, 2013, adopted the following: 1. City Council request Mayor Rob Ford to apologize for misleading the City of Toronto as to the existence of a video in which he appears to be involved in the use of drugs. 2. City Council urge Mayor Rob Ford to co-operate fully with the Toronto Police in their investigation of these matters by meeting with them in order to respond to questions arising from their investigation. 3. City Council request Mayor Rob Ford to apologize for writing a letter of reference for Alexander "Sandro" Lisi, an alleged drug dealer, on City of Toronto Mayor letterhead. 4. City Council request Mayor Ford to answer to Members of Council on the aforementioned subjects directly and not through the media. 5. City Council urge Mayor Rob Ford to take a temporary leave of absence to address his personal issues, then return to lead the City in the capacity for which he was elected. 6. City Council request the Integrity Commissioner to report back to City Council on the concerns raised in Part 1 through 5 above in regard to the Councillors' Code of Conduct. -

Can Toronto Be Run Like a Business? Observations on the First Two Years of the Ford Mayoralty in Torontoi

Can Toronto be Run Like a Business? Observations on the First Two Years of the Ford Mayoralty in Torontoi. Richard Stren Cities Centre University of Toronto Prepared for Presentation at the CPSA Annual Conference, Edmonton, Alberta June, 2012 Draft Only. No Citations or References without Express Consent of the Author. Mayoral candidate Rob Ford’s speech at the National Ethnic Press and Media Council of Canada (August 9, 2010): I come from the private sector, where my father started a labeling company….I’m proud to say that with the help of my brothers we have expanded to three locations in New Jersey, Chicago and Rexdale, and we now employ approximately 300 people….What I have seen in the last ten years is very disturbing at City Hall. I’ve seen taxes go up and services go down… In the private sector, we deliver, it’s very simple. The first rule is, the customer is always right. The second rule is, repeat the first rule…In politics we should take the exact same attitude….The taxpayer is the boss of all the civil servants….I really take a business approach to politics…in that customer service is lacking at city hall. …Customer service is number one. Downloaded on May 10, 2012 at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QOBotCHFRZE Video interview with Rob Ford on the day before the 2010 election: …[my brother and I have] run my father’s business that he started in 1962. We’ve expanded into Chicago and New Jersey. That’s the business approach I want to take to running the city. -

October 2018 Montreal, QC Canadian Parliament to Approve Filipino Heritage Month

Volume XXXVI No. 10 October 2018 Montreal, QC www.filipinostar.org Canadian Parliament to approve Filipino Heritage Month Paulina Corpuz Zalma Sahid. Liberal MP, Mike Colle, Liberal MPP, Neethan Shan, Councilor, Ward 42, first conceived the idea of Filipino Scarborough-Center Eglinton-Lawrence Scarborough-Rouge River Heritage month The House Commons is 1st, and a second reading on October 31st. For this reason, the executive the bill. Nineteen members have accelerating the passage of a private 25th to be followed by short speeches assistant of Madame Zahid signed on to be joint seconders of M- member Bill M-155 sponsored by a from members supporting the bill. recommended to have a Montreal 155: Sukh Daliwhal (Surrey-Newton), Liberal Party MP, Madame Salma Zahid News communicated by e-mail group to be organized to go to Ottawa Gary Anandasangaree (Scarborough- of Scarborough Center, who presented indicated that the bill has been moved and witness the historic vote in the first reading of the bill on October up for expected adoption on October Parliament adopting the passage of See Page 4 Filipino Heritage Canada just legalized pBy Goretcthe.n FWrazee,hPBoS Newcs Hoour,ualccdordinpg torthoe WforildtBa? nk, whereas Making Sense. Canada has a population of 36 million (Oct. 17, 2018) Recreational and a GDP of $1.7 trillion. marijuana in Canada became legal “A lot of countries are going to Wednesday, opening up a new multi- be looking at Canada and their ability billion dollar cannabis market to to make this a success,” said Colin businesses and investors. Busby, a research director at the The move will likely have Canadian-based Institute for Research significant economic implications for on Public Policy. -

News Release May 25, 2020 Councillors Welcome New Bike

News Release May 25, 2020 Councillors welcome new bike lanes along Bloor and University as part of City’s COVID-19 Response Toronto City Councillors Joe Cressy (Spadina-Fort York), Mike Layton (University-Rosedale), and Kristyn Wong-Tam (Toronto Centre) welcomed tHe announcement of new separated bike lanes tHis morning along Bloor Street and University Avenue, as part of tHe City’s ActiveTO program. THese bike lanes will make it easier for residents and front-line workers to cycle to work and practice pHysical distancing. As we begin to transition to recovery in Toronto and more businesses and workplaces open back up, How we will get around is a pressing challenge. For safe pHysical distancing we need to create alternative and safe metHods of transportation. Switching to driving isn’t an option for many, and even if it was, tHe resulting gridlock will grind traffic to a Halt, strangling our city and economy. It’s time for a new approach. Bike lanes on University Avenue (tHrougH Queen’s Park Crescent) and on Bloor Street will provide relief to two subway lines, creating more space on tHe subway for tHose wHo need to ride transit, and offering a new cycling option tHat is safe and uses our limited road space as efficiently as possible to move tHe most people. THe new separated bike lanes on tHese routes will connect cyclists to many of tHe area’s Hospitals and HealtH care facilities. Doctors for Safe Cycling, representing many pHysicians from downtown Hospitals, issued a letter earlier tHis montH asking for protected bike lanes, so tHat HealtH care workers, clients, and otHers can commute safely to tHe Hospital district by bike. -

Toronto City Council Enviro Report Card 2010-2014

TORONTO CITY COUNCIL ENVIRO REPORT CARD 2010-2014 TORONTO ENVIRONMENTAL ALLIANCE • JUNE 2014 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY hortly after the 2010 municipal election, TEA released a report noting that a majority of elected SCouncillors had committed to building a greener city. We were right but not in the way we expected to be. Councillors showed their commitment by protecting important green programs and services from being cut and had to put building a greener city on hold. We had hoped the 2010-14 term of City Council would lead to significant advancement of 6 priority green actions TEA had outlined as crucial to building a greener city. Sadly, we’ve seen little - if any - advancement in these actions. This is because much of the last 4 years has been spent by a slim majority of Councillors defending existing environmental policies and services from being cut or eliminated by the Mayor and his supporters; programs such as Community Environment Days, TTC service and tree canopy maintenance. Only in rare instances was Council proactive. For example, taking the next steps to grow the Greenbelt into Toronto; calling for an environmental assessment of Line 9. This report card does not evaluate individual Council members on their collective inaction in meeting the 2010 priorities because it is almost impossible to objectively grade individual Council members on this. Rather, it evaluates Council members on how they voted on key environmental issues. The results are interesting: • Average Grade: C+ • The Mayor failed and had the worst score. • 17 Councillors got A+ • 16 Councillors got F • 9 Councillors got between A and D In the end, the 2010-14 Council term can be best described as a battle between those who wanted to preserve green programs and those who wanted to dismantle them. -

Minutes of Meetings Held on May 25 and June 13, 2016

Toronto District School Board June 22, 2016 Regular Meeting June 22, 2016 A regular meeting was convened at 2:04 p.m. on Wednesday, June 22, 2016, in the Boardroom, 5050 Yonge Street, Toronto, with Robin Pilkey, Chair of the Board, presiding. The following members were present: Trustees Jennifer Arp, Alexander Brown, Sheila Cary- Meagher, Jerry Chadwick, Tiffany Ford, Gerri Gershon, Chris Glover, Pamela Gough, Parthi Kandavel, Shelley Laskin, Ken Lister, Ausma Malik, Chris Moise, Robin Pilkey, Neethan Shan, Marit Stiles, Jennifer Story, Chris Tonks, Manna Wong and Student Trustees Sammy Al Rubaie and Hamima Fattah. Regrets were received from Trustee David Smith. The office of Trustee held by Howard Kaplan was vacated following his death on April 11, 2016. The office of Trustee held by Michael Ford was vacated following his resignation on May 4, 2016. 1. Official Election Results for By-election in Toronto Centre-Rosedale, Ward 14 and Appointment to the Program and School Services Committee The office of Trustee held by Sheila Ward was vacated following her death on February 17, 2016. In addition, with the departure of former Trustee Ward and following the Organizational meeting held on December 1, 2015, a vacancy on the Program and School Services Committee was created. A by-election to fill the vacancy in Ward 14, Toronto Centre-Rosedale was held on Monday, June 20, 2016. The Board received a posting from City of Toronto’s City Clerk’s Office informing the Board of the results of the by-election (see page 16) and declaring Chris Moise elected as a member of the Toronto District School Board for the term of office June 21, 2016 to November 30, 2018.