Trinity Without Hierarchy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Total Christ Ecclesiology Introduction: After Modernity, What? Brian

Total Christ Ecclesiology Introduction: After Modernity, What? Brian McLaren: So what does it look like to conceive of a Christianity in another way that’s not modern? “Can you imagine what happens to the church, the whole Christian enterprise, when it has so thoroughly accommodated to modernity – so much so that it has no idea of any way Christianity could exist other than a modern way?1 Thomas Oden: Where did we get the twisted notion that orthodoxy is essentially a set of ideas rather than a living tradition of social experience? Our stereotype of orthodoxy is that of frozen dogma, rather than a warm continuity of human experience--of grandmothers teaching granddaughters, of feasts and stories, of rites and dancing. Orthodoxies are never best judged merely by their doctrinal ideas, but more so by their social products, the quality of their communities... They await being studied sociologically, not just theologically.2 • Post-Modern Yawn: o From modern reductionism(either-or small minded) to post-modern nothingism (anything minded) back to pre-modern? (both-ands?) • The cliché of a “re” prefix: Doug Pagitt’s Church Re-imagined…, Driscoll’s “Reformission…,” Chester and Timms “Reshaping…” etc o As much a protest as it is a search that dares to imagine spirituality and church practice no longer western facing and modernist • Neo-Denominational Unsettledness Lesslie Newbigin, (Foolishness to the Greeks: The Gospel and Western Culture); It is the common observation of sociologists of religion that denominationalism is the religious aspect of secularization. It is the form that religion takes in a culture controlled by the ideology of the Enlightenment. -

An Examination of Personal Salvation in the Theology of North American Evangelicalism: on the Road to a Theology of Social Justice

Wilfrid Laurier University Scholars Commons @ Laurier Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) 1980 An Examination of Personal Salvation in the Theology of North American Evangelicalism: On the Road to a Theology of Social Justice Robert F.J. Gmeindl Wilfrid Laurier University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd Part of the Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Gmeindl, Robert F.J., "An Examination of Personal Salvation in the Theology of North American Evangelicalism: On the Road to a Theology of Social Justice" (1980). Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive). 1421. https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd/1421 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) by an authorized administrator of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT AN EXAMINATION OF PERSONAL SALVATION IN THE THEOLOGY OF NORTH AMERICAN EVANGELICALISM: ON THE ROAD TO A THEOLOGY OF SOCIAL JUSTICE by Robert F.J. Gmeindl The question under consideration is the effect of the belief in personal salvation on the theology of North American Evangelicalism, for the purpose of developing a theology of social justice. This study is a preliminary investigation of the history of Evangelical individualism and the potential influence that individualism might have on Evangelical theology. Certain trends toward isolation and separation, as well as a tendency to neglect what I have called systemic evil, are examined to see how they may result from the Evangelical stress on individualism. -

Baptism on Behalf of the Dead”: 1 Corinthians 15:29 in Its Hellenistic Context

ABSTRACT “BAPTISM ON BEHALF OF THE DEAD”: 1 CORINTHIANS 15:29 IN ITS HELLENISTIC CONTEXT by Matthew Michael Connor This thesis analyzes 1 Corinthians 15:29 – a reference to “Baptism on behalf of the dead” – as an ancient Mediterranean ritual conducted on behalf of the dead. Scholars have been unable to reach a consensus regarding what Paul was referring to in this passage, with many commentators rejecting the most simple and obvious reading of the text. This paper analyzes the text and translation of 15:29, as well as the history of its interpretation before turning to the category of rituals on behalf of the dead in the ancient world. With a cultural predisposition toward ritual interaction between the living and the dead established in the ancient Mediterranean world, vicarious baptism in Corinth is approached using hybridity theory, which acknowledges the religious creativity of the Corinthians, standing in the contact zone between Paul’s Jesus cult and this longstanding Greek tradition of ritual actions performed on behalf of the dead. “BAPTISM ON BEHALF OF THE DEAD” 1 CORINTHIANS 15:29 IN ITS HELLENISTIC CONTEXT A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Comparative Religion by Matthew Michael Connor Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2010 Advisor________________________ James Constantine Hanges Reader_________________________ Elizabeth Wilson Reader_________________________ Deborah Lyons Contents Introduction 1 The Text and Its Reception 4 The Hellenistic Context 22 The Importance of Hybridity 41 Conclusion 56 Works Cited 59 ii Introduction The writings of the Apostle Paul, like the rest of the New Testament, are not without their mysteries. -

Study Guide for JOHN OWEN's the MORTIFICATION OF

Study Guide STUDY GUIDE FOR JOHN Owen’s THE MORTIFICATION OF SIN Rob Edwards THE BANNER OF TRUTH TRUST [] THE MORTIFICATION OF SIN THE BANNER OF TRUTH TRUST 3 Murrayfield Road, Edinburgh EH12 6EL, UK PO Box 621, Carlisle, PA 17013, USA * © The Banner of Truth Trust 2008 ISBN-13: 978 0 85151 999 9 * Typeset in 1O.5/14 pt Sabon Oldstyle Figures at The Banner of Truth Trust, Edinburgh. Printed in the USA by VersaPress, Inc., East Peoria, IL. * Scripture quotations are from The Holy Bible, English Standard Version, copyright © Crossway 2001 by Crossway Bibles, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers. Used by permission. All rights reserved. The page numbers in this Study Guide follow the page numbers in John Owen, The Mortification of Sin, Abridged and Made Easy to Read by Richard Rushing (Edinburgh: Banner of Truth, 2004) [] Study Guide Preface hile studying The Mortification of Sin by John WOwen there are a couple of things to keep in mind. First, this short book is focused on the doctrine of sanctification, to be distinguished from the doctrine of justification. In justification, the Christian is declared righteous, not because he is, in himself, righteous to any degree, but because of the righteousness of Christ alone. The Apostle Paul says in Romans 8:1 that ‘There is there- fore now no condemnation for those in Christ Jesus.’ This is the foundation on which the Christian begins the struggle against personal sin, which is the focus of sancti- fication. It is in sanctification that God begins tomake the Christian into what he has already declared the Christian to be, righteous. -

APPETIZER – Loving God with Our Minds DINE in – Because Jesus

THREE DANGERS… 1. You may widen your hypocrisy gap. Galatians 5:6; James 1:22-25 2. You may get bogged down in the paralysis of analysis. John 5:39-40 WEEK 1: PROLEGOMENA & GOSPELOLOGY: Loving God with all our Minds 3. You may fall in love with a system instead of your Saviour. WEEK 2: CHRISTOLOGY & BIBLIOLOGY – The Word of God, in Print and in Person WEEK 3: THEOLOGY PROPER/PATEROLOGY – The Person and Work of God John 3:8; 1 Corinthians 4:20 WEEK 4: ANTHROPOLOGY & HARMARTIOLOGY – Humanity and Sin WEEK 5: SOTERIOLOGY – Salvation Achieved and Received WEEK 6: ZOEOLOGY – The Christian Life (with Special Guest) THREE TIPS TO SURVIVE AND THRIVE… WEEK 7: PNEUMATOLOGY – The Person and Work of the Holy Spirit WEEK 8: ECCLESIOLOGY – The Identity and Practice of the Church 1. Look for the ONE THING that connects with you. WEEK 9: MISSIOLOGY – The Mission of the Church 2. Imagine how you will LIVE what you learn. WEEK 10: ESCHATOLOGY – Last Things 3. Do your homework – review, discuss, apply. APPETIZER – Loving God With Our Minds Mark 12:28-34; Romans 12:2 “THEOLOGY” = Theos (God) + Logos (Word) DINE IN – Because Jesus Is Lord THEOLOGY = Faith Seeking Understanding (Augustine & Anselm) Romans 10:9; 2 Corinthians 4:5 vs APOLOGETICS = Offering evidence for the faith we have Because Jesus is Lord (CHRISTOLOGY/GOSPELOLOGY)… THEOLOGY IS A LOT LIKE DOING A PUZZLE… • God is Love (THEOLOGY PROPER/PATEROLOGY) • SYSTEMATIC THEOLOGY = the picture of the puzzle • The Bible is Precious (BIBLIOLOGY) • BIBLICAL THEOLOGY = the pieces of the puzzle • We Are Priceless -

Systematic Theology I Theo 0531

Course Syllabus FALL 2013 SYSTEMATIC THEOLOGY I THEO 0531 MONDAY, 1:00 PM – 3:50 PM INSTRUCTOR: DR. DENNIS NGIEN Telephone number: 416 226 6620 ext. 2763 Email: [email protected] Office Hours: by appointment To access your course materials, go to your Tyndale email account: http://mytyndale.ca. Please note that all official Tyndale correspondence will be sent to your <@MyTyndale.ca e-mail account. For information how to access and forward Tyndale e-mails to your personal account, see http://www.tyndale.ca/it/live-at-edu. I. COURSE DESCRIPTION Systematic Theology I & II are designed to provide an introduction to the thematic study of Christian doctrine according to the evangelical protestant tradition. Systematic I acquaints students with the elemental building blocks of the Christian faith. The nature, sources, and task of theology will be considered, together with the following major doctrines: Revelations, Trinity, Person of Christ, Holy Spirit. Special attention will be given to the development of a missional, Trinitarian theology. Tyndale Seminary |1 II. LEARNING OUTCOMES At the end of the course, students should have: 1. Attitudes: a. increased appreciation for the value of theology in ministry and the Christian life. b. increased confidence in the authority of Scripture. 2. Information: a. the basic materials for further theological reflection and study. b. familiarity with major theological issues and lines of theological disagreement. 3. Skills: a. tools and skills for doing theological research. b. theological insights for practical situations in ministry. III. COURSE REQUIREMENTS: A. REQUIRED TEXTS: McGrath, Alister E. Christian Theology: An Introduction. 5th ed. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011. -

Donald Macleod. "The Doctrine of the Trinity,"

THE DOCTRINE OF THE TRINITY DONALD MACLEOD FREE CHURCH OF SCOTLAND COLLEGE, EDINBURGH I must begin with a word of caution. This is indeed holy ground and I don't want to treat it as some kind of academic exercise. We do indeed have a barrage of technical terms to reckon with but these are always, I hope, tools of worship and adoration rather than equipment for mental gymnastics. The problem with which the doctrine of the trinity is concerned contains three basic elements. First, there is the unity of God. God is one. Amid all the emphasis on God's triune-ness this remains the most basic point in our faith. "Hear, 0 Israel, J ehovah our God is one J ehovah" (Deut. 6:4). We must never lose sight of that. Pagan religions had a multiplicity of deities, virtually one to each life-force. In Christianity we have one, exclusive Source of life and energy: one Creator, one elemental Power, one Monarchy. However we go on to define other elements in our doctrine, we have to keep this as our guiding principle: no proposition can be allowed to tamper with the emphasis on divine unity. The second element in the problem is the deity of Christ. This is a point on which the New Testament is emphatic. It is found in all strands of the tradition: Christ is the os, Christ is kurios, Christ is Son ofGod, Christ is Son of Man. He has all the attributes of God. He performs all the functions of God. He enjoys all the prerogatives of God. -

Aspects of Arminian Soteriology in Methodist-Lutheran Ecumenical Dialogues in 20Th and 21St Century

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto ASPECTS OF ARMINIAN SOTERIOLOGY IN METHODIST-LUTHERAN ECUMENICAL DIALOGUES IN 20TH AND 21ST CENTURY Mikko Satama Master’s Thesis University of Helsinki Faculty of Theology Department of Systematic Theology Ecumenical Studies 18th January 2009 HELSINGIN YLIOPISTO − HELSINGFORS UNIVERSITET Tiedekunta/Osasto − Fakultet/Sektion Laitos − Institution Teologinen tiedekunta Systemaattisen teologian laitos Tekijä − Författare Mikko Satama Työn nimi − Arbetets title Aspects of Arminian Soteriology in Methodist-Lutheran Ecumenical Dialogues in 20th and 21st Century Oppiaine − Läroämne Ekumeniikka Työn laji − Arbetets art Aika − Datum Sivumäärä − Sidoantal Pro Gradu -tutkielma 18.1.2009 94 Tiivistelmä − Referat The aim of this thesis is to analyse the key ecumenical dialogues between Methodists and Lutherans from the perspective of Arminian soteriology and Methodist theology in general. The primary research question is defined as: “To what extent do the dialogues under analysis relate to Arminian soteriology?” By seeking an answer to this question, new knowledge is sought on the current soteriological position of the Methodist-Lutheran dialogues, the contemporary Methodist theology and the commonalities between the Lutheran and Arminian understanding of soteriology. This way the soteriological picture of the Methodist-Lutheran discussions is clarified. The dialogues under analysis were selected on the basis of versatility. Firstly, the sole world organisation level dialogue was chosen: The Church – Community of Grace. Additionally, the document World Methodist Council and the Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification is analysed as a supporting document. Secondly, a document concerning the discussions between two main-line churches in the United States of America was selected: Confessing Our Faith Together. -

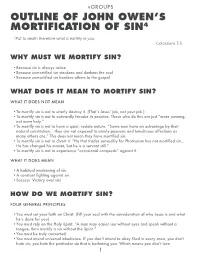

Outline of John Owen's Mortification of Sin4

vGROUPS OUTLINE OF JOHN OWEN’S MORTIFICATION OF SIN4 5Put to death therefore what is earthly in you… Colossians 3:5 WHY MUST WE MORTIFY SIN? • Because sin is always active • Because unmortified sin weakens and darkens the soul • Because unmortified sin hardens others to the gospel WHAT DOES IT MEAN TO MORTIFY SIN? WHAT IT DOES NOT MEAN • To mortify sin is not to utterly destroy it. (That’s Jesus’ job, not your job.) • To mortify sin is not to outwardly forsake its practice. Those who do this are just “more cunning; not more holy.” • To mortify sin is not to have a quiet, sedate nature. “Some men have an advantage by their natural constitution… they are not exposed to unruly passions and tumultuous affections as many others are.” This does not mean they have mortified sin. • To mortify sin is not to divert it. “He that trades sensuality for Pharisaism has not mortified sin… He has changed his master, but he is a servant still.” • To mortify sin is not to experience “occasional conquests” against it. WHAT IT DOES MEAN • A habitual weakening of sin. • A constant fighting against sin. • Success. Victory over sin! HOW DO WE MORTIFY SIN? FOUR GENERAL PRINCIPLES • You must set your faith on Christ. (Fill your soul with the consideration of who Jesus is and what he’s done for you) • You must rely on the Holy Spirit. “A man may easier see without eyes and speak without a tongue, than mortify a sin without the Spirit.” • You must be truly converted. • You must intend universal obedience. -

Do Christians Have a Worldview?

LET GO AND LET GOD? A Survey and Analysis of Keswick Theology ANDREW DAVID NASELLI FOREWORD BY THOMAS R. SCHREINER Copyright © 2010 by Andrew David Naselli This book packs an extraordinary amount of useful summary, critical analysis, and pastoral reflection into short compass. One does not have to agree with every opinion to recognize that this is a comprehensive and penetrating analysis of Keswick theology down to 1920. The book will do the most good, however, if it encourages readers in a more faithful way to pursue that holiness without which we will not see the Lord (Hebrews 12:14). D. A. Carson Research Professor of New Testament Trinity Evangelical Divinity School Deerfield, Illinois For years popular Christian teachers have been telling us the secret key to the victorious, higher, deeper, more abundant Christian life. We’ve been told just to “let go and let God.” If you’ve heard that teaching, you’ll want to read this book—the definitive history and critique of second-blessing theology. You’ll learn not only where this theology went wrong, but will also discover afresh the well-worn old paths of biblical faithfulness and holiness. Andy Naselli is an extraordinarily careful scholar who leaves no stone unturned, but also a compassionate guide who longs to help and serve the church of Jesus Christ. Readers of this work will be instructed and encouraged in their Christian walk. Justin Taylor Vice President of Editorial; Managing editor, ESV Study Bible Crossway Blogger at Between Two Worlds Wheaton, Illinois Keswick theology cast a wide and long shadow over twentieth-century church life in America. -

Reformation Christology: Some Luther Starting Points

Volume 7l:2 April 2007 Table of Contents -- - - - - - - Talking about the Son of God: An Introduction ............................. 98 Recent Archaeology of Galilee and the Interpretation of Texts from the Galilean Ministry of Jesus Mark T. Schuler .......................................................................... 99 Response by Daniel E. Paavola ..............................................117 Jesus and the Gnostic Gospels Jeffrey Kloha .............................................................................121 Response by Charles R. Schulz ........................................144 Reformatia Christology: Some Luther Starting Points Robert Rosin ........................................................................... 147 Response by Naomichi Masaki ..............................................168 American Christianity and Its Jesuses Lawrence R. Rast Jr ...... .. .. ... .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 175 Response by Rod Rosenbladt ................................................. 194 Theological Observer The Lost Tomb of Jesus? ........................................................ 199 CTQ 71 (2007):147-168 Reformation Christology: Some Luther Starting Points Robert Rosin "Reformation Christology" is an impossible topic in the space allotted. A narrower topic, relatively speaking, is Martin Luther's Christology, which leaves only about one hundred and twenty heavyweight volumes, each the proverbial blunt instrument that could do in the person foolish enough to think that Luther can be managed in this space. Nor -

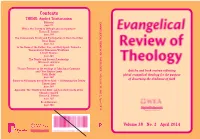

Contents THEME: Applied Trinitarianism Editorial EVANGELICAL REVIEW of THEOLOGY Page 99 Why Is the Trinity So Difficult and So Important? THOMAS K

Contents THEME: Applied Trinitarianism Editorial REVIEW OF THEOLOGY EVANGELICAL page 99 Why is the Trinity so Difficult and so Important? THOMAS K. JOHNSON page 100 The Consummate Trinity and Participation in the Life of God BRIAN EDGAR page 112 In the Name of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit: Toward a Transcultural Trinitarian Worldview J. SCOTT HORRELL page 126 The Trinity and Servant-Leadership WILLIAM P. ATKINSON page 138 Vestigia Trinitatis in the writings of John Amos Comenius and Clive Staples Lewis 38, NO 2, April 2014 VOLUME Articles and book reviews reflecting PAVEL HOŠEK global evangelical theology for the purpose page 151 of discerning the obedience of faith ‘Bones to Philosophy, but milke to faith’ – Celebrating the Trinity TERSUR ABEN page 160 Appendix: The Trinity in the Bible and Selected Creeds of the Church compiled THOMAS K. JOHNSON page 169 Book Reviews page 186 WORLD EVANGELICAL ALLIANCE Theological Commission Volume 38 No. 2 April 2014 WORLD EVANGELICAL ALLIANCE Theological Commission Evangelical Review of Theology GENERAL EDITOR: THOMAS SCHIRRMACHER Articles and book reviews reflecting global evangelical theology for the purpose of discerning the obedience of faith Published by WORLD EVANGELICAL ALLIANCE Theological Commission for WORLD EVANGELICAL ALLIANCE Theological Commission ERT (2014) 38:2, 99 Volume 38 No. 2 April 2014 Editorial There was a remarkable phenomenon Intellectuals and drunkards could Copyright © 2014 World Evangelical Alliance Theological Commission in the ancient world. A group of people confess their faith/philosophy togeth- who were self-consciously marginal- er and experience how the big ques- ized, uneducated, poor, and morally tions of history and existence were questionable became a moral-cultural answered in a creed they could all force that created orphanages, formed remember.