Baptism on Behalf of the Dead”: 1 Corinthians 15:29 in Its Hellenistic Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Total Christ Ecclesiology Introduction: After Modernity, What? Brian

Total Christ Ecclesiology Introduction: After Modernity, What? Brian McLaren: So what does it look like to conceive of a Christianity in another way that’s not modern? “Can you imagine what happens to the church, the whole Christian enterprise, when it has so thoroughly accommodated to modernity – so much so that it has no idea of any way Christianity could exist other than a modern way?1 Thomas Oden: Where did we get the twisted notion that orthodoxy is essentially a set of ideas rather than a living tradition of social experience? Our stereotype of orthodoxy is that of frozen dogma, rather than a warm continuity of human experience--of grandmothers teaching granddaughters, of feasts and stories, of rites and dancing. Orthodoxies are never best judged merely by their doctrinal ideas, but more so by their social products, the quality of their communities... They await being studied sociologically, not just theologically.2 • Post-Modern Yawn: o From modern reductionism(either-or small minded) to post-modern nothingism (anything minded) back to pre-modern? (both-ands?) • The cliché of a “re” prefix: Doug Pagitt’s Church Re-imagined…, Driscoll’s “Reformission…,” Chester and Timms “Reshaping…” etc o As much a protest as it is a search that dares to imagine spirituality and church practice no longer western facing and modernist • Neo-Denominational Unsettledness Lesslie Newbigin, (Foolishness to the Greeks: The Gospel and Western Culture); It is the common observation of sociologists of religion that denominationalism is the religious aspect of secularization. It is the form that religion takes in a culture controlled by the ideology of the Enlightenment. -

Study Guide for JOHN OWEN's the MORTIFICATION OF

Study Guide STUDY GUIDE FOR JOHN Owen’s THE MORTIFICATION OF SIN Rob Edwards THE BANNER OF TRUTH TRUST [] THE MORTIFICATION OF SIN THE BANNER OF TRUTH TRUST 3 Murrayfield Road, Edinburgh EH12 6EL, UK PO Box 621, Carlisle, PA 17013, USA * © The Banner of Truth Trust 2008 ISBN-13: 978 0 85151 999 9 * Typeset in 1O.5/14 pt Sabon Oldstyle Figures at The Banner of Truth Trust, Edinburgh. Printed in the USA by VersaPress, Inc., East Peoria, IL. * Scripture quotations are from The Holy Bible, English Standard Version, copyright © Crossway 2001 by Crossway Bibles, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers. Used by permission. All rights reserved. The page numbers in this Study Guide follow the page numbers in John Owen, The Mortification of Sin, Abridged and Made Easy to Read by Richard Rushing (Edinburgh: Banner of Truth, 2004) [] Study Guide Preface hile studying The Mortification of Sin by John WOwen there are a couple of things to keep in mind. First, this short book is focused on the doctrine of sanctification, to be distinguished from the doctrine of justification. In justification, the Christian is declared righteous, not because he is, in himself, righteous to any degree, but because of the righteousness of Christ alone. The Apostle Paul says in Romans 8:1 that ‘There is there- fore now no condemnation for those in Christ Jesus.’ This is the foundation on which the Christian begins the struggle against personal sin, which is the focus of sancti- fication. It is in sanctification that God begins tomake the Christian into what he has already declared the Christian to be, righteous. -

1 Corinthians 15:1-9 “Jesus: Most Important”

1 Corinthians 15:1-9 “Jesus: Most Important” Scripture: 1 Corinthians 15:1-9 Memory Verse: 1 Corinthians 15:3-4 “For I delivered to you as of first importance…that Christ died for our sins according to the Scriptures, and that He was buried, and that He was raised on the third day according to the Scriptures.” (NASB) Lesson Focus: We will emphasize what the apostle Paul emphasizes in this text: That knowing and trusting in the death, burial, and resurrection of Jesus Christ is absolutely essential to our faith. It is of “first importance” because it is real and it really matters. Then we will challenge the kids to make it real in their own lives. Activities and Crafts: Coloring Picture of Empty Tomb, Crossword Puzzle of different terms from lesson, Bring It Home Discussion for 3rd – 5th. Craft for all Grades: Wooden Crosses or Egg/Cross Decorations Starter Activity: Most Important Things! We will keep all of the kids in the Summit Room for our starter activity. We will watch a silly video that will transition us into some discussion about most important things. Q: What did Barbie think was really important in life? Glitter! This is silly as there are a lot more important things in life than glitter. Some things are more important than others. Which of these do you think is more important? 1) Water or SmartPhone 2) Bread or Doughnuts 3) Exercise or Fortnite (video games) * 4) Valentine’s Day or Easter 5) Being Good or Believing in Jesus As we have studied through the gospel of John, we have seen over and over again that John’s goal in writing this book is so that we would BELIEVE. -

“For This Ordinance Belongeth to My House”: the Practice of Baptism for the Dead Outside the Nauvoo Temple

Alexander L. Baugh: Baptism for the Dead Outside Temples 47 “For This Ordinance Belongeth to My House”: The Practice of Baptism for the Dead Outside the Nauvoo Temple Alexander L. Baugh The Elders’ Journal of July 1838, published in Far West, Missouri, includ- ed a series of twenty questions related to Mormonism. The answers to the questions bear the editorial pen of Joseph Smith. Question number sixteen posed the following query: “If the Mormon doctrine is true, what has become of all those who have died since the days of the apostles?” The Prophet answered, “All those who have not had an opportunity of hearing the gospel, and being administered to by an inspired man in the flesh, must have it hereafter before they can be finally judged.”1 The Prophet’s thought is clear—the dead must have someone in mortality administer the saving ordinances for them to be saved in the kingdom of God. Significantly, the answer given by the Prophet marks his first known statement concerning the doctrine of vicari- ous work for the dead. However, it was not until more than two years later that the principle was put into practice.2 On 15 August 1840, Joseph Smith preached the funeral sermon of Seymour Brunson during which time he declared for the first time the doc- trine of baptism for the dead.3 Unfortunately, there are no contemporary accounts of the Prophet’s discourse. However, Simon Baker was present at the funeral services and later stated that during the meeting the Prophet read extensively from 1 Corinthians 15, then noted a particular widow in the congregation whose son had died without baptism. -

Lesson 24 - the Resurrection of Christ - 1 Corinthians 15:1-11

STUDYING THE BOOK OF 1 CORINTHIANS IN SMALL GROUP DISCUSSIONS Lesson 24 - The Resurrection of Christ - 1 Corinthians 15:1-11 Read the following verses in the New International Version or a translation of your choice. Then discuss the questions that follow. Questions should be studied by each individual before your discussion group meets. Materials may be copied and used for Bible study purposes. Not to be sold. 1CO 15:1 Now, brothers, I want to remind you of the gospel I preached to you, which you received and on which you have taken your stand. [2] By this gospel you are saved, if you hold firmly to the word I preached to you. Otherwise, you have believed in vain. 1CO 15:3 For what I received I passed on to you as of first importance: that Christ died for our sins according to the Scriptures, [4] that he was buried, that he was raised on the third day according to the Scriptures, [5] and that he appeared to Peter, and then to the Twelve. [6] After that, he appeared to more than five hundred of the brothers at the same time, most of whom are still living, though some have fallen asleep. [7] Then he appeared to James, then to all the apostles, [8] and last of all he appeared to me also, as to one abnormally born. 1CO 15:9 For I am the least of the apostles and do not even deserve to be called an apostle, because I persecuted the church of God. [10] But by the grace of God I am what I am, and his grace to me was not without effect. -

Sunday School Notes June 14, 2020 Apollos, Aquila and Pricilla and Paul Signing Off Read: 1 Corinthians 16:12-24 Aquila and Pr

Sunday School Notes June 14, 2020 Apollos, Aquila and Pricilla and Paul Signing Off Read: 1 Corinthians 16:12-24 Aquila and Priscilla greet you warmly (1 Corinthians 16:19-20) Acts 18:1-11, 18-21; Romans 16:3-5a Apollos (1 Corinthians 16:12) Acts 18:24-19:1; 1 Corinthians 3:1-9, 21-23 A great exhortation (1 Corinthians 16:13) Paul signs off the letter, in his own handwriting. (1 Corinthians 16:21-24) 2 Corinthians 12:7-10; Galatians 4:13-16; 6:11; 2 Thessalonians 3:17; Acts 22:30-23:5 June 7, 2020 Read: 1 Corinthians 16:1-24 Giving, Hospitality, and news about Paul’s friends About giving and hospitality (1 Corinthians 16:1-9) Acts 11:27-29; Romans 12:13 and 15:23-29; 2 Corinthians 8:1-9; 9:6-8, 12-15; Galatians 6:10; Philemon 1-2, 20-22; Hebrews 13:1-2; 1 Peter 4:8-9 News about: Timothy (1 Corinthians 16:10-11) Acts 16:1-3; 1 Timothy 1:3-8; 1 Corinthians 4:15-17; Philippians 2:19-24 The household of Stephanas (1 Corinthians 16:15-18) Most scholars assume these three men Stephanas, Fortunatus and Achaicus carried the Corinthian’s letter with questions to Paul and then returned to Corinth with 1 Corinthians from Paul. May 31, 2020 Living in the Natural Life with our Eyes on our Glorious Future Read: 1 Corinthians 15:35-58 → Compare to 2 Corinthians 4:16-18; 5:1-10; Romans 8:18-27; Galatians 5:16- 26; Ephesians 6:10-18 May 24, 2020 Read: 1 Corinthians 15:12-34 Compare 1 Corinthians 15:18-19 with 1 Thessalonians 4:13-18. -

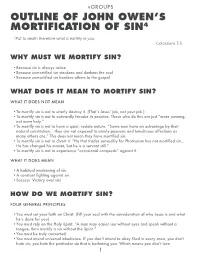

Outline of John Owen's Mortification of Sin4

vGROUPS OUTLINE OF JOHN OWEN’S MORTIFICATION OF SIN4 5Put to death therefore what is earthly in you… Colossians 3:5 WHY MUST WE MORTIFY SIN? • Because sin is always active • Because unmortified sin weakens and darkens the soul • Because unmortified sin hardens others to the gospel WHAT DOES IT MEAN TO MORTIFY SIN? WHAT IT DOES NOT MEAN • To mortify sin is not to utterly destroy it. (That’s Jesus’ job, not your job.) • To mortify sin is not to outwardly forsake its practice. Those who do this are just “more cunning; not more holy.” • To mortify sin is not to have a quiet, sedate nature. “Some men have an advantage by their natural constitution… they are not exposed to unruly passions and tumultuous affections as many others are.” This does not mean they have mortified sin. • To mortify sin is not to divert it. “He that trades sensuality for Pharisaism has not mortified sin… He has changed his master, but he is a servant still.” • To mortify sin is not to experience “occasional conquests” against it. WHAT IT DOES MEAN • A habitual weakening of sin. • A constant fighting against sin. • Success. Victory over sin! HOW DO WE MORTIFY SIN? FOUR GENERAL PRINCIPLES • You must set your faith on Christ. (Fill your soul with the consideration of who Jesus is and what he’s done for you) • You must rely on the Holy Spirit. “A man may easier see without eyes and speak without a tongue, than mortify a sin without the Spirit.” • You must be truly converted. • You must intend universal obedience. -

Do Christians Have a Worldview?

LET GO AND LET GOD? A Survey and Analysis of Keswick Theology ANDREW DAVID NASELLI FOREWORD BY THOMAS R. SCHREINER Copyright © 2010 by Andrew David Naselli This book packs an extraordinary amount of useful summary, critical analysis, and pastoral reflection into short compass. One does not have to agree with every opinion to recognize that this is a comprehensive and penetrating analysis of Keswick theology down to 1920. The book will do the most good, however, if it encourages readers in a more faithful way to pursue that holiness without which we will not see the Lord (Hebrews 12:14). D. A. Carson Research Professor of New Testament Trinity Evangelical Divinity School Deerfield, Illinois For years popular Christian teachers have been telling us the secret key to the victorious, higher, deeper, more abundant Christian life. We’ve been told just to “let go and let God.” If you’ve heard that teaching, you’ll want to read this book—the definitive history and critique of second-blessing theology. You’ll learn not only where this theology went wrong, but will also discover afresh the well-worn old paths of biblical faithfulness and holiness. Andy Naselli is an extraordinarily careful scholar who leaves no stone unturned, but also a compassionate guide who longs to help and serve the church of Jesus Christ. Readers of this work will be instructed and encouraged in their Christian walk. Justin Taylor Vice President of Editorial; Managing editor, ESV Study Bible Crossway Blogger at Between Two Worlds Wheaton, Illinois Keswick theology cast a wide and long shadow over twentieth-century church life in America. -

Reformation Christology: Some Luther Starting Points

Volume 7l:2 April 2007 Table of Contents -- - - - - - - Talking about the Son of God: An Introduction ............................. 98 Recent Archaeology of Galilee and the Interpretation of Texts from the Galilean Ministry of Jesus Mark T. Schuler .......................................................................... 99 Response by Daniel E. Paavola ..............................................117 Jesus and the Gnostic Gospels Jeffrey Kloha .............................................................................121 Response by Charles R. Schulz ........................................144 Reformatia Christology: Some Luther Starting Points Robert Rosin ........................................................................... 147 Response by Naomichi Masaki ..............................................168 American Christianity and Its Jesuses Lawrence R. Rast Jr ...... .. .. ... .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 175 Response by Rod Rosenbladt ................................................. 194 Theological Observer The Lost Tomb of Jesus? ........................................................ 199 CTQ 71 (2007):147-168 Reformation Christology: Some Luther Starting Points Robert Rosin "Reformation Christology" is an impossible topic in the space allotted. A narrower topic, relatively speaking, is Martin Luther's Christology, which leaves only about one hundred and twenty heavyweight volumes, each the proverbial blunt instrument that could do in the person foolish enough to think that Luther can be managed in this space. Nor -

Trinity Without Hierarchy

“Written as a contribution to an important evangelical debate, this erudite volume deserves a readership across ecclesial divisions. All Thomists, for example, will find Tyler Wittman’s brilliant account of Aquinas’s Trinitarian theology to be necessary reading. May this volume’s Trinitarian reflections have a healing and unitive effect, not only among the evangelicals involved in the debate, but also across ecclesiastical lines so that we ‘may all be one’!” —Matthew Levering, James N. and Mary D. Perry Jr. Chair of Theology, Mundelein Seminary, and coeditor of The Oxford Handbook of the Trinity “This new collection of Trinitarian studies is theologically sensitive, biblically attuned, and historically concerned. Everyone interested in the future of Trin- itarian theology within evangelical Protestantism will find this book a good and encouraging guide.” —Lewis Ayres, Durham University and Australian Catholic University “In recent years, the waters of evangelical Trinitarian theology have been roiled and muddied by unfortunate debates about the subordination of the Son. The very fine essays collected in this volume make genuine progress in exegetical, biblical, as well as historical and systematic theology, and they will do much to help bring an end to this debate.” —Thomas H. McCall, Professor of Biblical and Systematic Theology, Trinity Evangelical Divinity School and Professorial Fellow in Exegetical and Analytic Theology, University of St Andrews “Orthodoxy matters. Who is the God we are confessing, worshipping, and living for in faith and obedience? Who is the God whom we long to share eternal communion with on the new heaven and the new earth? What theo- logical cultures are we receiving? It is incumbent upon the church to retrieve an orthodox confession and pass that down to the next generation. -

CHAPTER 16 (Change the Order!) David Renwick, June 2, 2021

1 CORINTHIANS Chapter 15/16 CHAPTER 16 (change the order!) David Renwick, June 2, 2021 SCHEDULE FINAL GREETINGS 15:19-23 April 14- June 2, 2021 • 19The churches of Asia send greetings. • Aquila and Prisca, together with the church in their house, greet 1. Background you warmly in the Lord. 2. Restoring Ruptured Relationships (1 Cor 1-3; 14) ▪ See Romans 16:3 3. Sex in the City (1 Cor 5-7) • 20All the brothers and sisters send greetings. 4. Winning by Losing (1 Cor 8-10) • Greet one another with a holy kiss. 5. Did Paul Hate Women? (1 Cor 11) 6. Spiritually Mature? (1 Cor 11-14) 21I, Paul, write this greeting with my own hand. 22 7. Life After Death (1 Cor 15) Anyone who has no love for the Lord: 8. Generosity/Conclusion (1 Cor 16) Let there be a curse. OF ULTIMATE IMPORTANCE: Love Jesus! NOT: End of our Series . ▪ the wrong “leader/party;” Tonight’s Topic: 1 Corinthians 15 & 16 ▪ the wrong knowledge; ▪ the wrong spirituality LAST TIME – Resurrection of the Body Our Lord, come! -- focused first on “the body” 23The grace of the Lord Jesus be with you. -- a theme repeated in various ways in Paul’s writings and in the gospels 24My love be with all of you in Christ Jesus. e.g., • Lord’s Supper -- This is my body broken for you PAUL’S TRAVEL PLANS 16:5-9 • Incarnation -- the word became flesh (embodied), and dwelt 5I will visit you after passing through Macedonia among us —for I intend to pass through Macedonia— • Creation -- Part of God’s good material creation: God made our ▪ Philippi bodies the way they are on purpose ▪ Thessalonica • Sin – Bodies weakened (infected?) morally and physically by sin 6and perhaps I will stay with you or even spend the winter, • Bodies subject to death so that you may send me on my way, wherever I go. -

Lifegroup Questions Overcome Based On: 1 Corinthians 15 March 30, 2014

LifeGroup Questions Overcome Based On: 1 Corinthians 15 March 30, 2014 Overview 1 Corinthians 15 A lady once asked Vernon McGee this question: “Our preacher said that on Easter, Jesus just swooned on the cross and that the disciples nursed Him back to health. What do you think?" Vernon replied, "Dear sister, beat your preacher with a leather whip with 39 heavy strokes, nail him to a cross, hang him in the sun for six hours, run a spear through his heart, embalm him, put him in an airless tomb for three days, and see what happens!" The resurrection is the cornerstone of the Christian faith. Paul states that without the resurrection our faith is in vain. It is because of the knowledge of the power of the resurrection that Paul wrote, “Where, O death, is your victory? Where, O death, is your sting?” The sting of death is sin, and the power of sin is the law. 57 But thanks be to God! He gives us the victory through our Lord Jesus Christ.” Bible Study: 1 Corinthians 15 1. Generally speaking, why do you think the cross of Christ is spoken more about than the tomb of Christ? 2. How do you view the various challenges you face in life? What is your general attitude when life doesn’t go the way you want it to? 3. Everyone has challenges they want to overcome. Take a few moments and think about some challenges you are currently facing. In what ways does the gospel give you hope and strength to overcome life’s challenges? 4.