Democratizing Luminato: Private-Public Partnerships Hang in Delicate Balance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 2012 New York Guitar Festival® John Schaefer, Host David Spelman and A.J

Merkin Concert Hall Thursday, January 19, 2012 at 7:30 pm Kaufman Center presents The 2012 New York Guitar Festival® John Schaefer, host David Spelman and A.J. Benson, curators Silent Films/Live Guitars HOWARD FISHMAN Buster Keaton’s The Frozen North (1922, 17 minutes) Intermission CALIFONE Buster Keaton’s Go West (1925, 69 minutes) TIM RUTILI, JIM BECKER, BEN MASSARELLA and JOE ADAMIK About the Artists Howard Fishman began his career on the streets of New Orleans and in the subways of NYC, experiences that still resonate in his “disarmingly un-showbizy” concerts (Backstage). A pioneer of the Brooklyn music scene, Fishman “brings a feeling to a room that is reunion-like. Everyone there is part of a community…it can’t be helped.” (11211 Magazine). A testament to his wide-ranging appeal, Fishman has appeared on bills with such diverse artists as Odetta, Yo-Yo Ma, Maceo Parker, Robyn Hitchcock, Taj Mahal and Allen Holdsworth. He is a frequent NPR guest, making feature-length appearances on Fresh Air, World Cafe, Leonard Lopate and Word of Mouth, and has recently been featured as a headlining performer in the American Songbook at Lincoln Center, The Steppenwolf Theatre and at Duke Performances in North Carolina. Fishman’s travels and omnivorous curiosity inform his constantly-expanding repertoire of special projects, from his original oratorio we are destroyed, about The Donner Party, to his multi-media travelogue No Further Instructions, to his New Orleans- inspired Biting Fish Brass Band. His tenth CD, Moon Country, was released in October. Howard Fishman is a storyteller, a seeker, a cultural anthropologist, and “an important force in creative music” (allmusic.com). -

Hto Park (Central Waterfront)

HtO Park (Central Waterfront) http://urbantoronto.ca/forum/printthread.php?s=bdb9f0791b0c9cf2cb1d... HtO Park (Central Waterfront) Printable View Show 40 post(s) from this thread on one page Page 1 of 9 1 2 3 ... Last AlvinofDiaspar 2006-Nov-16, 14:09 HtO Park (Central Waterfront) From the Star: A vision beyond the urban beach Nov. 16, 2006. 01:00 AM CHRISTOPHER HUME Janet Rosenberg may be in a hurry, but unfortunately Toronto isn't. One of the city's leading landscape architects, Rosenberg desperately wants Toronto to get off its collective butt and get going. She's getting tired of waiting. Take HtO, for example, the "urban beach" at the foot of John St. at Queens Quay W. her firm designed three years ago. The project is underway and slated to open next spring, finally, only two years behind schedule. Much of that time has been spent jumping through bureaucratic hoops. Dealing with the various agencies alone was enough to slow construction to a crawl. Now, however, the results can be seen; the large concrete terraces that reach down to the very waters of Lake Ontario have been poured and the hole that will contain a huge sandpit has been dug and lined. Even a few of the bright yellow umbrellas have been installed. Eventually there will be 39, the bulk still to come. Willow trees have also been planted on mounds and benches installed. Of course, changes were made along the way. After West 8 of Rotterdam won the central waterfront redesign competition last summer, the beach was moved closer to Queens Quay in anticipation of reducing the street from four lanes to two. -

PB22.8.8 KPMB Architects

PB22.8.8 KPMB Architects 17 April 2017 Lourdes Bettencourt 2nd Floor, West Tower, City Hall 100 Queen Street West Toronto, Ontario M5H 2N2 Dear Lourdes, A Partnership of Re: 70 Lowther Avenue Corporations Bruce Kuwabara Marianne McKenna I am writing to recommend that 70 Lowther Avenue be listed and designated as a heritage Shirley Blumberg building. Principals Christopher Couse Phyllis Crawford Mitchell Hall Located on the northeast corner of Admiral Road and Lowther Avenue in the Annex Luigi LaRocca neighbourhood of Toronto, 70 Lowther Avenue is both architecturally and historically Goran Milosevic important, having been designed by Charles John Gibson (1862-1935) for Reginald Northcote in Directors Hany Iwamura 1901. Gibson was an eminent and prolific Canadian architect who designed many residences Philip Marjeram throughout Toronto in the late 19th and early 20th century. Amanda Sebris Senior Associates Andrew Dyke 70 Lowther represents a very good example of a corner house marked by tall east and south David Jesson facing gables and a longer side on Lowther Avenue that takes advantage of south light. The Robert Sims design is representative of the quality of residential design that characterized the growth of the Associates Kevin Bridgman Annex when it was a new neighbourhood subdivision north of Bloor Street. Steven Casey David Constable Mark Jaffar What is very valuable and effective about the house is how it respects the setbacks both to the Carolyn Lee Angela Lim west on Admiral Road and the south on Lowther Avenue, reinforcing the continuity of the Glenn MacMullin streetscapes and landscaped setbacks that characterize the Annex. -

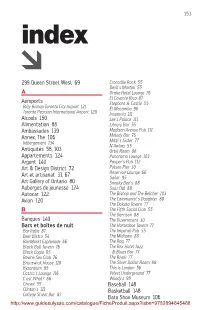

Escale À Toronto

153 index 299 Queen Street West 69 Crocodile Rock 55 Devil’s Martini 55 A Drake Hotel Lounge 76 El Covento Rico 87 Aéroports Elephant & Castle 55 Billy Bishop Toronto City Airport 121 El Mocambo 96 Toronto Pearson International Airport 120 Insomnia 111 Alcools 150 Lee’s Palace 111 Alimentation 88 Library Bar 55 Ambassades 139 Madison Avenue Pub 111 Annex, The 106 Melody Bar 76 hébergement 134 Mitzi’s Sister 77 N’Awlins 55 Antiquités 58, 103 Orbit Room 88 Appartements 124 Panorama Lounge 103 Argent 140 Pauper’s Pub 112 Art & Design District 72 Polson Pier 30 Reservoir Lounge 66 Art et artisanat 31, 67 Sailor 95 Art Gallery of Ontario 80 Sneaky Dee’s 88 Auberges de jeunesse 124 Souz Dal 88 Autocar 122 The Bishop and The Belcher 103 Avion 120 The Communist’s Daughter 88 The Dakota Tavern 77 B The Fifth Social Club 55 The Garrison 88 Banques 140 The Guvernment 30 Bars et boîtes de nuit The Horseshoe Tavern 77 Bar Italia 87 The Imperial Pub 55 Beer Bistro 54 The Midtown 88 BierMarkt Esplanade 66 The Raq 77 Black Bull Tavern 76 The Rex Hotel Jazz Black Eagle 95 & Blues Bar 77 Bovine Sex Club 76 The Rivoli 77 Brunswick House 110 The Silver Dollar Room 96 Byzantium 95 This is London 56 Castro’s Lounge 116 Velvet Underground 77 C’est What? 66 Woody’s 95 Cheval 55 Baseball 148 Clinton’s 111 Basketball 148 College Street Bar 87 Bata Shoe Museum 106 http://www.guidesulysse.com/catalogue/FicheProduit.aspx?isbn=9782894645468 154 Beaches International Jazz E Festival 144 Eaton Centre 48 Beaches, The 112 Edge Walk 37 Bières 150 Électricité 145 Bières, -

Festival Guide

FESTIVAL GUIDE DU GUÍA DEL GUIDE FESTIVAL FESTIVAL July 10–August 15, 2015 10 juillet au 15 août 2015 10 julio – 15 agosto 2015 LEAD PARTNER PARTENAIRE PRINCIPAL SOCIO PRINCIPAL PREMIER PARTNERS GRANDS PARTENAIRES SOCIOS PREMIERES OPENING CEREMONY CREATIVE PARTNER OFFICIAL BROADCASTER PARTENAIRE CRÉATIF POUR LA CÉRÉMONIE D’OUVERTURE DIFFUSEUR OFFICIEL SOCIO CREATIVO PARA LA CEREMONIA DE INAUGURACIÓN EMISORA OFICIAL OFFICIAL SUPPLIERS FOURNISSEURS OFFICIELS PROVEEDORES OFICIALES PROUD SUPPORTERS FIERS PARRAINEURS COLABORADORES PRINCIPALES Acklands-Grainger ATCO Structures & Logistics Ltd. Bochner Eye Institute BT/A Advertising Burnbrae Farms The Canadian Press Carbon60 Networks The Carpenters’ Union CGC Inc. Division Sports-Rep Inc. ELEIKO EllisDon-Ledcor Esri Canada eSSENTIAL Accessibility Freeman Audio Visual Canada Gateman-Milloy Inc. George Brown College Gerflor Gold Medal Systems La Presse LifeLabs Medical Laboratory Services MAC Cosmetics Minavox Modu-loc Fence Rentals Morningstar Hospitality Services Inc. Nautique Boats ONRoute Highway Service Centres Ontario Power Generation PortsToronto Riedel Communications Roots Rosetta Stone SpiderTech Sportsnet 590 The Fan S4OPTIK Starwood Hotels and Resorts TBM Service Group TLN Telelatino Toronto Port Lands Company UP Express VIA Rail Canada VOIT Vision Critical Waste Management Yonex YouAchieve ZOLL 407 ETR FUNDING PARTIES HOST CITY HOST FIRST NATION BAILLEURS DE FONDS VILLE HÔTE PREMIÈRE NATION HÔTE PROVEEDORES DE FINANCIAMIENTO CIUDAD ANFITRIONA PRIMERA NACIÓN ANFITRIONA Live Sites/Sites -

Toronto Central Waterfront Public Forum #2

TORONTO CENTRAL WATERFRONT PUBLIC FORUM #2 Queens Quay Revitalization EA Bathurst Street to Lower Jarvis Street Municipal Class Environmental Assessment (Schedule C) December 08, 2008 1 WATERFRONT TORONTO UPDATE 2 Central Waterfront International Design Competition 3 Waterfront Toronto Long Term Plan – Central Waterfront 4 Waterfront Toronto Long Term Plan – Central Waterfront 5 Waterfront Toronto Long Term Plan – Central Waterfront 6 Waterfront Toronto Long Term Plan – Central Waterfront 7 East Bayfront Waters Edge Promenade: Design Underway 8 Spadina Wavedeck: Opened September 2008 9 Spadina Wavedeck: Opened September 2008 10 Spadina Wavedeck: Opened September 2008 Metropolis Article 11 Rees Wavedeck: Construction Underway 12 Simcoe Wavedeck: Construction Underway 13 Spadina Bridge: Construction Early-2009 14 What Have We Been Doing for the Past 11 Months? • Consider and follow up on comments from Public Forum 1 • Assess baseline technical feasibility of design alternatives – Over 90 meetings in total: • City and TTC technical staff • Partner agencies •Stakeholders • Landowners/Property Managers • Adjacent project efforts • Advanced transit and traffic modelling • Develop Alternative Design Concepts and Evaluation (Phase 3) • Coordination with East Bayfront Transit EA 15 Study Area: Revised 16 Overview • Review of EA Phases 1 & 2 from Public Forum #1: January 2008 • EA Phase 3: Alternative Design Alternatives – Long list of Design Alternatives – Evaluation of Design Alternatives • Next Steps – Evaluation Criteria for Shortlisted Design -

Making Space for Culture: Community Consultation Summaries

Making Space for Culture Community Consultation Summaries April 2014 Cover Photos courtesy (clockwise from top left) Harbourfront Centre, TIFF Bell Lightbox, Artscape, City of Toronto Museum Services Back Cover: Manifesto Festival; Photo courtesy of Manifesto Documentation Team Making Space for Culture: Overview BACKGROUND Making Space for Culture is a long-term planning project led 1. Develop awareness among citizens, staff, City Councillors by the City of Toronto, Cultural Services on the subject of cultural and potential partners and funders of the needs of cultural infrastructure city-wide. Funded by the Province of Ontario, the and community arts organizations, either resident or providing study builds on the first recommendation made in Creative Capital programming in their ward, for suitable, accessible facilities, Gains: An Action Plan for Toronto, a report endorsed by City equipment and other capital needs. Council in May 2011. The report recommends “that the City ensure 2. Assist with decision-making regarding infrastructure a supply of affordable, sustainable cultural space” for use by cultural investment in cultural assets. industries, not-for-profit organizations and community groups in the City of Toronto. While there has been considerable public and private 3. Disseminate knowledge regarding Section 37 as it relates investment in major cultural facilities within the city in the past to cultural facilities to City Councillors, City staff, cultural decade, the provision of accessible, sustainable space for small and organizations, and other interested parties. mid-size organizations is a key factor in ensuring a vibrant cultural 4. Develop greater shared knowledge and strengthen community. collaboration and partnerships across City divisions and agencies with real estate portfolios, as a by-product of the The overall objective of the Making Space for Culture project is to consultation process. -

Now Until Jun 16. NXNE Music Festival. Yonge and Dundas. Nxne

hello ANNUAL SUMMER GUIDE Jun 14-16. Taste of Little Italy. College St. Jun 21-30. Toronto Jazz Festival. from Bathurst to Shaw. tolittleitaly.com Featuring Diana Ross and Norah Jones. hello torontojazz.com Now until Jun 16. NXNE Music Festival. Jun 14-16. Great Canadian Greek Fest. Yonge and Dundas. nxne.com Food, entertainment and market. Free. Jun 22. Arkells. Budweiser Stage. $45+. Exhibition Place. gcgfest.com budweiserstage.org Now until Jun 23. Luminato Festival. Celebrating art, music, theatre and dance. Jun 15-16. Dragon Boat Race Festival. Jun 22. Cycle for Sight. 125K, 100K, 50K luminatofestival.com Toronto Centre Island. dragonboats.com and 25K bike ride supporting the Foundation Fighting Blindness. ffb.ca Jun 15-Aug 22. Outdoor Picture Show. Now until Jun 23. Pride Month. Parade Jun Thursday nights in parks around the city. Jun 22. Pride and Remembrance Run. 23 at 2pm on Church St. pridetoronto.com topictureshow.com 5K run and 3K walk. priderun.org Now until Jun 23. The Book of Mormon. Jun 16. Father’s Day Heritage Train Ride Jun 22. Argonauts Home Opener vs. The musical. $35+. mirvish.com (Uxbridge). ydhr.ca Hamilton Tiger-Cats. argonauts.ca Now until Jun 27. Toronto Japanese Film Jun 16. Father’s Day Brunch Buffet. Craft Jun 23. Brunch in the Vineyard. Wine Festival (TJFF). $12+. jccc.on.ca Beer Market. craftbeermarket.ca/Toronto and food pairing. Jackson-Triggs Winery. $75. niagarawinefestival.com Now until Aug 21. Fresh Air Fitness Jun 17. The ABBA Show. $79+. sonycentre.ca Jun 25. Hugh Jackman. $105+. (Mississauga). Wednesdays at 7pm. -

Rees Street Park Design Brief

MAY 15 2018 // INNOVATIVE DESIGN COMPETITION REES STREET PARK Design Competition Brief > 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 4 2. GOALS (FROM THE RFQ) 7 3. PROGRAM FOR REES STREET PARK 8 3.1 Required Design Elements: 8 3.2 Site Opportunities and Constraints 14 3.3 Servicing & infrastructure 18 3 Rees Street Park and Queens Quay, looking southeast, April 2018 4 1. INTRODUCTION Waterfront Toronto and the City of Toronto Parks Forestry and Recreation Department are sponsoring this six-week design competition to produce bold and innovative park designs for York Street Park and Rees Street Park in the Central Waterfront. Each of these sites will become important elements of the Toronto waterfront’s growing collection of beautiful, sustainable and popular public open spaces along Queens Quay. Five teams representing a range of different landscape design philosophies have been selected to focus on the Rees Street Park site based on the program set out in this Competition Brief. The program consists of nine Required Design Elements identified through community consultation, as well as a number of physical site opportunities and constraints that must be addressed in the design proposals. The design competition will kick off on May 15, 2018 with an all-day orientation session – at which the teams will hear presentations from Waterfront Toronto, government officials, and key stakeholders – and a tour of the site. At the end of June, completed proposals will be put on public exhibition during which time input will be solicited from stakeholders, city staff, and the general public. A jury comprised of distinguished design and arts professionals will receive reports from these groups, and then select a winning proposal to be recommended to Waterfront Toronto and City of Toronto Parks Forestry and Recreation. -

General Executive Board Meetings Book 1 James J

REPORT OF THE GENERAL EXECUTIVE BOARD MEETINGS BOOK 1 JAMES J. CLAFFEY, JR., Thirteenth Vice REPORT OF THE President GENERAL EXECUTIVE In addition to the members of the Board, those BOARD MEETING present included: International Trustees Patricia A. White, Carlos Cota and Andrew C. Oyaas; CLC HELD AT THE Delegate Siobhan Vipond; Assistant to the President SHERATON GRAND Sean McGuire; Director of Communications Matthew Cain; Director of Broadcast Sandra England; LOS ANGELES, CA Political Director J. Walter Cahill, Assistant Political JANUARY 29 – FEBRUARY 2, 2018 Director Erika Dinkel-Smith; Assistant Directors of Motion Picture and Television Production Daniel CALL TO ORDER Mahoney and Vanessa Holtgrewe; Co-Director of The regular Mid-Winter meeting of the General Stagecraft Anthony DePaulo, Assistant Director of Executive Board of the International Alliance of Theatrical Stagecraft D. Joseph Hartnett; Assistant Director Stage Employees, Moving Picture Technicians, Artists of Education and Training Robyn Cavanagh; and Allied Crafts of the United States, Its Territories and International Representatives Ben Adams, Steve Canada convened at 10:00 a.m. on Monday, January 29, Aredas, Christopher “Radar” Bateman, Steve Belsky, 2018 in the California BCEF Ballrooms of the Sheraton Jim Brett, Peter DaPrato, Don Gandolini, Jr., Ron Grand, Los Angeles, California. Garcia, John Gorey, Scott Harbinson, Krista Hurdon, Kent Jorgensen, Steve Kaplan, Mark Kiracofe, Peter Marley, Fran O’Hern, Joanne Sanders, Stasia Savage, ROLL CALL Lyle Trachtenberg, and Jason Vergnano; Staff General Secretary-Treasurer James B. Wood called members Leslie DePree, Asha Nandlal, Alejandra the roll and recorded the following members present: Tomais, Marcia Lewis and MaryAnn Kelly. MATTHEW D. -

Waterfront Shores Corporation

Waterfront Shores Corporation The Waterfront Shores Corporation (“WSC”) is a single purpose entity established by a consortium of four experienced partners for the purpose of acquiring Pier 8, Hamilton. WSC combines the vast residential and mixed-use development experience of Cityzen Development Corporation (“Cityzen”) and Fernbrook Homes Group (“Fernbrook”), the specialized soil remediation and construction skills of GFL Environmental Inc. (“GFL”) and the real estate investment expertise of Greybrook Realty Partners Inc. (“Greybrook”). Cityzen Development Corporation Founded in 2003, Head Office at Suite 308, 56 The Esplanade, Toronto, ON, M5E 1A7 Cityzen is a multi-faceted real estate developer, founded by Sam Crignano, and it will lead the development of the Pier 8 site. Its unique comprehensive approach encompasses real estate experience that spans the entire spectrum of real estate sectors. With a passion for visionary urban design, Cityzen, is committed to excellence, dedicated to creating beautiful and iconic design-driven developments that enhance the quality of life and place while remaining sensitive to community and environmental concerns. Cityzen has developed a well-earned reputation by working with award-winning architects and designers to further push the boundaries of creating innovative urban communities that are designed to enhance urban neighbourhoods. Through a network of strategic alliances and partnerships, Cityzen has, in a relatively short period of time, adopted a leadership role in the industry. The company’s -

Friday, November 16, 8Pm, 2007 Umass Fine Arts Center Concert Hall

Friday, November 16, 8pm, 2007 UMass Fine Arts Center Concert Hall Unbroken Chain: The Grateful Dead in Music, Culture, and Memory As part of a public symposium, November 16-18, UMass Amherst American Beauty Project featuring Jim Lauderdale Ollabelle Catherine Russell, Larry Campbell Theresa Williams Conceived by David Spelman Producer and Artistic Director of the New York premier Program will be announced from the stage Unbroken Chain is presented by the UMass Amherst Graduate School, Department of History, Fine Arts Center, University Outreach AND University Reserach. Sponsored by The Valley Advocate, 93.9 The River, WGBY TV57 and JR Lyman Co. About the Program "The American Beauty Project" is a special tribute concert to the Grateful Dead's most important and best-loved albums, Working Man's Dead and American Beauty. In January 2007, an all-star lineup of musicians that Relix magazine called "a dream team of performers" gave the premier of this concert in front of an over-flowing crowd at the World Financial Center's Winter Garden in New York City. The New York Times' Jon Pareles wrote that the concert gave "New life to a Dead classic... and mirrored the eclecticism of the Dead," and a Variety review said that the event brought "a back- porch feel to the canyons of Gotham's financial district. The perf's real fire came courtesy of acts that like to tear open the original structures of the source material and reassemble the parts afresh - an approach well-suited to the honorees' legacy." Now, a select group of those performers, including Ollabelle, Larry Campbell & Teresa Williams, Catherine Russell, and Jim Lauderdale are taking the show on the road.