Burgundian Costume.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe European History Yearbook Jahrbuch Für Europäische Geschichte

Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe European History Yearbook Jahrbuch für Europäische Geschichte Edited by Johannes Paulmann in cooperation with Markus Friedrich and Nick Stargardt Volume 20 Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe Edited by Cornelia Aust, Denise Klein, and Thomas Weller Edited at Leibniz-Institut für Europäische Geschichte by Johannes Paulmann in cooperation with Markus Friedrich and Nick Stargardt Founding Editor: Heinz Duchhardt ISBN 978-3-11-063204-0 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-063594-2 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-063238-5 ISSN 1616-6485 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 04. International License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number:2019944682 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2019 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published in open access at www.degruyter.com. Typesetting: Integra Software Services Pvt. Ltd. Printing and Binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck Cover image: Eustaţie Altini: Portrait of a woman, 1813–1815 © National Museum of Art, Bucharest www.degruyter.com Contents Cornelia Aust, Denise Klein, and Thomas Weller Introduction 1 Gabriel Guarino “The Antipathy between French and Spaniards”: Dress, Gender, and Identity in the Court Society of Early Modern -

Destabilizing Shakespeare: Reimagining Character Design in 1 Henry VI

Connecticut College Digital Commons @ Connecticut College Self-Designed Majors Honors Papers Self-Designed Majors 2021 Destabilizing Shakespeare: Reimagining Character Design in 1 Henry VI Carly Sponzo Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/selfdesignedhp Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons This Honors Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Self-Designed Majors at Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Self-Designed Majors Honors Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author. Connecticut College Destabilizing Shakespeare: Reimagining Character Design in 1 Henry VI A Thesis Submitted to the Department of Student-Designed Interdisciplinary Majors and Minors in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree in Costume Design by Carly Sponzo May 2021 Acknowledgements I could not have poured my soul into the following pages had it not been for the inspiration and support I was blessed with from an innumerable amount of individuals and organizations, friends and strangers. First and foremost, I would like to extend the depths of my gratitude to my advisor, mentor, costume-expert-wizard and great friend, Sabrina Notarfrancisco. The value of her endless faith and encouragement, even when I was ready to dunk every garment into the trash bin, cannot be understated. I promise to crash next year’s course with lots of cake. To my readers, Lina Wilder and Denis Ferhatovic - I can’t believe anyone would read this much of something I wrote. -

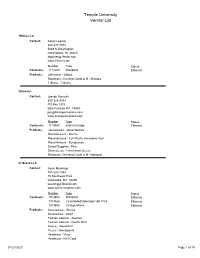

Temple University Vendor List

Temple University Vendor List 19Nine LLC Contact: Aaron Loomer 224-217-7073 5868 N Washington Indianapolis, IN 46220 [email protected] www.19nine.com Number Type Status Contracts: 1112269 Standard Effective Products: Otherwear - Shorts Stationary, Greeting Cards & N - Stickers T-Shirts - T-Shirts 3Click Inc Contact: Joseph Domosh 833-325-4253 PO Box 2315 Bala Cynwyd, PA 19004 [email protected] www.3clickpromotions.com Number Type Status Contracts: 1114550 Internal Usage Effective Products: Housewares - Water Bottles Miscellaneous - Koozie Miscellaneous - Cell Phone Accessory Item Miscellaneous - Sunglasses School Supplies - Pen Short sleeve - t-shirt short sleeve Stationary, Greeting Cards & N - Notepad 47 Brand LLC Contact: Kevin Meisinger 781-320-1384 15 Southwest Park Westwood, MA 02090 [email protected] www.twinsenterprise.com Number Type Status Contracts: 1013854 Standard Effective 1013856 Co-branded/Operation Hat Trick Effective 1013855 Vintage Marks Effective Products: Accessories - Gloves Accessories - Scarf Fashion Apparel - Sweater Fashion Apparel - Rugby Shirt Fleece - Sweatshirt Fleece - Sweatpants Headwear - Visor Headwear - Knit Caps 01/21/2020 Page 1 of 79 Headwear - Baseball Cap Mens/Unisex Socks - Socks Otherwear - Shorts Replica Football - Football Jersey Replica Hockey - Hockey Jersey T-Shirts - T-Shirts Womens Apparel - Womens Sweatpants Womens Apparel - Capris Womens Apparel - Womens Sweatshirt Womens Apparel - Dress Womens Apparel - Sweater 4imprint Inc. Contact: Karla Kohlmann 866-624-3694 101 Commerce -

Correct Clothing for Historical Interpreters in Living History Museums Laura Marie Poresky Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1997 Correct clothing for historical interpreters in living history museums Laura Marie Poresky Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the American Material Culture Commons, Fashion Design Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Poresky, Laura Marie, "Correct clothing for historical interpreters in living history museums" (1997). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 16993. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/16993 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Correct clothing for historical interpreters in jiving history museums by Laura Marie Poresky A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major: Textiles and Clothing Major Professor: Dr. Jane Farrell-Beck Iowa State University Ames. Iowa 1997 II Graduate College Iowa State University This is to certify that the Master's thesis of Laura Marie Poresky has met the thesis requirements of Iowa State University Signatures have been redacted for privacy III TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT v INTRODUCTlON 1 Justification -

15Th C Italian Clothing

15th C clothing for men and women THL Peryn Rose Whytehorse Barony of the South Downs Meridies February 2015 CAMICIA/CAMISA (M/F). The chemise, made usually of linen, but occasionally of cotton or silk. 1494 In the earlier part of the century, the camicia is a functional washable layer of clothing worn between the skin and the outer woollen or silk garments. However, as the Quattrocento progresses, the chemise, revealed through slits and slashes down the sleeves and the bodice, and around the neckline, becomes more decorated with embroidered bands around the collar and cuffs. There must have been regional variations also; e.g. men's shirts 'a modo di Firenze' (Strozzi, op. Finish inside cit., p. 100). edges of sleeves on both sides 1452-66 1488 Definitions from Dress in Renaissance Italy, 1400-1500, by Jacqueline Herald, printed by Humanities Press: NJ, 1981. 1496 1478 Inventories Monna Bamba 1424 - 7 camicie usate 1476-78 Wedding present to Francesco de Medici 1433 – 17 chamicie Household of Puccio Pucci – 18 camicie da donna 1452-66 1452 1460s 1476-84 1460-64 1460-64 GAMURRA/CAMMURA/CAMORA (F). The Tuscan term for the simple dress worn directly over the woman's chemise (camicia). 1476-84 In the north of Italy, it is known by the terms zupa, zipa or socha. The gamurra is worn by women of all classes. It is both functional and informal, being worn on its own at home, and covered by some form of overgarment such as the cioppa, mantello, pellanda or vestimento out-of-doors or on a more formal occasion. -

The Well Dress'd Peasant

TheThe WWellell DrDress’dess’d Peasant:Peasant: 1616thth CenturCenturyy FlemishFlemish WWorkingwomen’orkingwomen’ss ClothingClothing by Drea Leed The Well-Dress’d Peasant: 16th Century Flemish Workingwoman’s Dress By Drea Leed Costume & Dressmaker Press Trinidad, Colorado ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author and publisher wish to thank the following institutions for their help with the color images for the cover and interior color plates. Copyright for these images is retained by them, in accordance with international copyright laws. The images are used with permission. Cover A Marketwoman and Vegetable Stand, by Pieter Aertsen © Bildarchiv Preüssuscher Kulturbesitz Märkishes Ufer 16-18 D-10179 Berlin Germany Inside front cover Harvest Time by Pieter Aertsen and Plates 1, 3 The Pancake Bakery by Pieter Aertsen Harvest Time (A Vegetable and Fruit Stall) by Pieter Aertsen © Museum Boijmans van Beuningen Museumpark 18-20 CX Rotterdam The Netherlands Plate 2 (Centerfold) The Meal Scene (Allegorie van de onvoorzichtigheid) by Joachim Beuckelaer © Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten Plaatsnijderstraat2, B-2000 Antwerp Belgium © November 2000 by Drea Leed © November 2000 by Costume & Dressmaker Press Published by Costume & Dressmaker Press 606 West Baca Street Trinidad Colorado 81082 USA http://www.costumemag.com All rights reserved. No part of this work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means - graphic, electronic or mechanical, including scanning, photocopying, recording, taping or information storage -

Fashion Collection, 1900 - Bulk Dates: 1940-1960

Fashion Collection, 1900 - bulk dates: 1940-1960 Special Collections Department/Long Island Studies Institute Contact Information: Special Collections Department Axinn Library, Room 032 123 Hofstra University Hempstead, NY 11549 Phone: (516) 463-6411, or 463-6404 Fax: (516) 463-6442 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.hofstra.edu/Libraries/SpecialCollections Compiled by: [J. Boucher] Last updated by: Date Completed: [2003] [M. O’Connor] [Aug. 24, 2006] Fashion Collection, 1900 - (bulk dates, 1940-1960) 11 c.f. The Fashion Collection was established by a donation from Eunice Siegelheim and her sister Bernice Wolfson. The core of the collection is 16 hats from the 1930s through the 1950s. The sisters, Eunice and Bernice wore these hats to social events on Long Island. Many were made and purchased in Brooklyn and other parts of New York. The Fashion Collection captures the spirit of various eras with artifacts and illustrations showing how people dressed for various social events. Many of the items in the Fashion Collection correspond to items in other collections, such as photographs from the Image Collection as well as the Long Island History of Sports Collection. Photographs of street scenes in the Image Collection show women of different eras on the sidewalk promenades of Long Island Towns. The Long Island History of Sports Collection includes photographs and programs from Belmont Park’s circa 1910. In addition to the hats, the collection contains other clothing artifacts such as men’s ties, hatboxes, dresses and shoes, from Ms. Siegelheim as well as other donors. The collection also supports fashion research with a run of American Fabrics Magazine, a trade publication that served the garment industry in the 1940s and 1950s. -

TO CLOTHE a FOOL : a Study of the Apparel Appropriate for the European Court Fool 1300 - 1700

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 1979 TO CLOTHE A FOOL : A Study of the Apparel Appropriate for the European Court Fool 1300 - 1700 Virginia Lee Futcher Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/4621 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TO CLOTHE A FOOL A Study of the Apparel Appropriate for the European Court Fool 1300 - 1700 by VIRGINIA LEE FUTCHER Submitted to the Faculty of the School of th e Arts of Virginia Commonwealth University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree Master of Fine Arts Richmond, Virginia December, 1979 TO CLOTHE A FOOL A Study of the Apparel Appropriate :for the European Court Fool 1300 - 1700 by VIRGINIA LEE FUTCHER Approved: I A'- ------ =:- ::-"':'"" Advisor TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS iii PREFACE ix CHAPTE R ONE: An Overview of the Fool 's Clothing . I CHAPTER TWO: Fools From Art. • • . 8 CHAP TE R THREE: Fools From Costume Texts . 53 CONCLUSION . 80 APPENDIX •• 82 BIBLIOGRAPHY. 88 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure Page I. Ass's Eared Hood 1 2. One Point Hood . 1 3. Combination Eared/Pointed Hood 2 4. Ass 's Eared Hood Variation 2 5. Bird Head Hood . 2 6. -

Les Coiffures

Semaine 14 – ORTHOGRAPHE ET VOCABULAIRE Les coiffures 1. Trouvez les 30 fautes d’orthographe cachées dans ce teste extrait de la revue Animagine : Louis XIII perdit ses cheveux à trente ans et inaugura le porc port de la perruque. L’usage de ces postiches faits de faux cheveux était fréquent pour les vieillards des classes privilégiées, par contre un jeune noble aurait eu honte de porter cet attribut. Mais ce que le Roi fait devient coutume et la nouvelle coife coiffe royale faite de cheveux artificiels fut adoptée par la Cour. Louis XIV possédait une perruque différente pour chaque occupation de la journée, cette mode perdurat perdura sous Louis XV. Pendant le règne de Louis XVI, toute la bonne société portait perruque et les perruquiers pouvaient vivre heureux. A cette époque, on comptait environ douze cents perruquiers qui tenaient leur privilège(s) de Saint Louis et employaient six mille personnes. La poudre à perruque était un amidon vendu à prix d’or. Les parfumeurs assuraient détenir un extraordinaire secret de fabrication, alors qu’il ne s’agissait que d’un amidon réduis réduit en poudre et passer passé au travers d’un tamis de soie très serrée. Les boutiques de perruques n’étaient pas réputées pour leur hygiène… C’est la révolution de 1789 qui sonna le glas des perruques, le symbole d’une noblesse vieillissante. Alors, l’expression « tête a à perruque » désignait les vieillards obstinés et nostalgiques qui conservaient l’habitude des faux cheveux, et plus généralement toute personne démodée et vieillotte. Il fallut attendre la fin du XIXème siècle pour voir ressurgir resurgir une profession qui avait quasiment disparu(e). -

Draping Period Costumes: Classical Greek to Victorian the FOCAL PRESS COSTUME TOPICS SERIES

Draping Period Costumes: Classical Greek to Victorian THE FOCAL PRESS COSTUME TOPICS SERIES Costumes are one of the most important aspects of any production. Th ey are essential tools that create a new reality for both the actor and audience member, which is why you want them to look fl awless! Luckily, we’re here to help with Th e Focal Press Costume Topics Series; off ering books that explain how to design, construct, and accessorize costumes from a variety of genres and time periods. Step-by-step projects ensure you never get lost or lose inspiration for your design. Let us lend you a hand (or a needle or a comb) with your next costume endeavor! Titles in Th e Focal Press Costume Topics Series: Draping Period Costumes: Classical Greek to Victorian Sharon Sobel First published 2013 by Focal Press 70 Blanchard Rd Suite 402 Burlington, MA 01803 Simultaneously published in the UK by Focal Press 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Focal Press is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2013 Taylor & Francis Th e right of Sharon Sobel to be identifi ed as author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. -

“Ena Silkes Tröya” – Clothing Bequests in Finnish Medieval Wills

“Ena silkes tröya” – clothing bequests in Finnish medieval wills Piia Lempiäinen ABSTRACT This paper studies bequeathing practices and clothing terminology in medieval Finnish wills found from the Diplo- matarium Fennicum database and compares them to other Nordic countries. The use of wills as a source for dress and textile studies is discussed and the concept of clothing bequests is examined. The material shows how clothing donations demonstrate the medieval practice of gift-giving, where favours, allegiance, and power were traded and negotiated with tangible objects, such as clothing, that had both monetary as well as symbolic value. After this, clothing terminology is discussed with the help of previous Nordic research and different clothing terms used in the wills are presented and analysed. The study indicates that clothing was bequeathed in the same ways as in other Nordic countries using similar terms. Finally it is suggested that the source-based terminology should be used together with modern neutral terminology especially when the language of the research is different from the language of the sources to accurately communicate the information to others. Keywords: Middle Ages, wills, clothing, dress terminology, Finland, gift-giving. 1. Introduction In the Middle Ages even mundane, everyday items had value because of the high cost of materials and labour. Items were used, reused, resold, and recycled many times during their life cycles. Clothing and textiles were no different, and they were worn down, repaired, altered to fi t the new fashions, and in the end used as rags or shrouds (Østergård 2004; Crowfoot et al. 2006). Clothing was also com- monly passed down from generation to generation, and items of clothing are quite often mentioned in wills. -

Ancient Andean Headgear: Medium and Measure of Cultural Identity Niki R

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 1994 Ancient Andean Headgear: Medium and Measure of Cultural Identity Niki R. Clark Jefferson County Historical Museum Amy Oakland Rodman California State University at Hayward Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Materials Conservation Commons, Art Practice Commons, Fashion Design Commons, Fiber, Textile, and Weaving Arts Commons, Fine Arts Commons, and the Museum Studies Commons Clark, Niki R. and Rodman, Amy Oakland, "Ancient Andean Headgear: Medium and Measure of Cultural Identity" (1994). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 1055. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/1055 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Clark, Niki R., and Amy Oakland Rodman. “Ancient Andean Headgear: Medium and Measure of Cultural Identity.” Contact, Crossover, Continuity: Proceedings of the Fourth Biennial Symposium of the Textile Society of America, September 22–24, 1994 (Los Angeles, CA: Textile Society of America, Inc., 1995). ANCIENT ANDEAN HEADGEAR; MEDIUM AND MEASURE OF CULTURAL IDENTITY Niki R. Clark Amy Oakland Rodman Jefferson County Historical Museum Art Dept., California State University 210 Madison, Port Townsend, WA 98368 at Hayward, Hayward, CA 94542 Introduction From the earliest recorded periods of southern Andean history, distinctive clothing styles have served to identity specific socio-cultural groups and provide clues about cultural origins.