Simply-Proust-1596556548

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Land of Horses 2020

LAND OF HORSES 2020 « Far back, far back in our dark soul the horse prances… The horse, the horse! The symbol of surging potency and power of movement, of action in man! D.H. Lawrence EDITORIAL With its rich equine heritage, Normandy is the very definition of an area of equine excellence. From the Norman cavalry that enabled William the Conqueror to accede to the throne of England to the current champions who are winning equestrian sports events and races throughout the world, this historical and living heritage is closely connected to the distinctive features of Normandy, to its history, its culture and to its specific way of life. Whether you are attending emblematic events, visiting historical sites or heading through the gates of a stud farm, discovering the world of Horses in « Normandy is an opportunity to explore an authentic, dynamic and passionate region! Laurence MEUNIER Normandy Horse Council President SOMMAIRE > HORSE IN NORMANDY P. 5-13 • normandy the world’s stables • légendary horses • horse vocabulary INSPIRATIONS P. 14-21 • the fantastic five • athletes in action • les chevaux font le show IIDEAS FOR STAYS P. 22-29 • 24h in deauville • in the heart of the stud farm • from the meadow to the tracks, 100% racing • hooves and manes in le perche • seashells and equines DESTINATIONS P. 30-55 • deauville • cabourg and pays d’auge • le pin stud farm • le perche • saint-lô and cotentin • mont-saint-michel’s bay • rouen SADDLE UP ! < P. 56-60 CABOURG AND LE PIN PAYS D’AUGE STUD P. 36-39 FARM DEAUVILLE P. -

Retriever (Labrador)

Health - DNA Test Report: DNA - HNPK Gundog - Retriever (Labrador) Dog Name Reg No DOB Sex Sire Dam Test Date Test Result A SENSE OF PLEASURE'S EL TORO AT AV0901389 27/08/2017 Dog BLACKSUGAR LUIS WATERLINE'S SELLERIA 27/11/2018 Clear BALLADOOLE (IMP DEU) (ATCAQ02385BEL) A SENSE OF PLEASURE'S GET LUCKY (IMP AV0904592 09/04/2018 Dog CLEARCREEK BONAVENTURE A SENSE OF PLEASURE'S TEA FOR 27/11/2018 Clear DEU) WINDSOCK TWO (IMP DEU) AALINCARREY PUMPKIN AT LADROW AT04277704 30/10/2016 Bitch MATTAND EXODUS AALINCARREY SUMMER LOVE 20/11/2018 Carrier AALINCARREY SUMMER LOVE AR03425707 19/08/2014 Bitch BRIGHTON SARRACENIA (IMP POL) AALINCARREY FAIRY DUST 27/08/2019 Carrier AALINCARREY SUMMER MAGIC AR03425706 19/08/2014 Dog BRIGHTON SARRACENIA (IMP POL) AALINCARREY FAIRY DUST 23/08/2017 Clear AALINCARREY WISPA AT01657504 09/04/2016 Bitch AALINCARREY MANNANAN AFINMORE AIRS AND GRACES 03/03/2020 Clear AARDVAR WINCHESTER AH02202701 09/05/2007 Dog AMBERSTOPE BLUE MOON TISSALIAN GIGI 12/09/2016 Clear AARDVAR WOODWARD AR03033605 25/08/2014 Dog AMBERSTOPE REBEL YELL CAMBREMER SEE THE STARS 29/11/2016 Carrier AARDVAR ZOLI AU00841405 31/01/2017 Bitch AARDVAR WINCHESTER CAMBREMER SEE THE STARS 12/04/2017 Clear ABBEYSTEAD GLAMOUR AT TANRONENS AW03454808 20/08/2019 Bitch GLOBETROTTER LAB'S VALLEY AT ABBEYSTEAD HOPE 25/02/2021 Clear BRIGBURN (IMP SVK) ABBEYSTEAD HORATIO OF HASELORHILL AU01380005 07/03/2017 Dog ROCHEBY HORN BLOWER HASELORHILL ENCORE 05/12/2019 Clear ABBEYSTEAD PAGEANT AT RUMHILL AV01630402 10/04/2018 Dog PARADOCS BELLWETHER HEATH HASELORHILL ENCORE -

Pynchon Nods: Proust in Gravity's Rainbow Date: 2012 Volume: 1 Issue: 1 URL: DOI: 10.7766/Orbit.V1.1.30

Orbit: Writing Around Pynchon https://www.pynchon.net ISSN: 2044-4095 Author(s): Erik Ketzan Affiliation(s): Institut für Deutsche Sprache, Mannheim, Germany Title: Pynchon Nods: Proust in Gravity's Rainbow Date: 2012 Volume: 1 Issue: 1 URL: https://www.pynchon.net/owap/article/view/30 DOI: 10.7766/orbit.v1.1.30 Abstract: This paper argues that Pynchon may allude to Marcel Proust through the character Marcel in Part 4 of Gravity's Rainbow and, if so, what that could mean. I trace the textual clues that relate to Proust and analyze what Pynchon may be saying about a fellow great experimental writer. Pynchon Nods: Proust in Gravity's Rainbow Erik Ketzan Editorial note: a previous draft of this paper appeared on The Modern Word in 2010. Remember the "Floundering Four" part in Gravity's Rainbow? It's a short story of sorts that takes place in a city of the future called Raketen-Stadt (German for "Rocket City") and features a cast of comic book-style super heroes called the Floundering Four. One of them is named Marcel, and I submit that he is meant as some kind of representation of the great Marcel Proust. Only eight pages long, the Floundering Four section is a parody/riff on a sci-fi comic book story, loosely patterned on The Fantastic Four by Marvel Comics. It appears near the end of Gravity's Rainbow among a set of thirteen chapterettes, each one a fragmentary "text". As Pynchon scholar Steven Weisenburger explains, "A variety of discourses, modes and forms are parodied in the… subsections.. -

Jonathan Greenberg

Losing Track of Time Jonathan Greenberg Ottessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation tells a story of doing nothing; it is an antinovel whose heroine attempts to sleep for a year in order to lose track of time. This desire to lose track of time constitutes a refusal of plot, a satiric and passive- aggressive rejection of the kinds of narrative sequences that novels typically employ but that, Moshfegh implies, offer nothing but accommodation to an unhealthy late capitalist society. Yet the effort to stifle plot is revealed, paradoxically, as an ambi- tion to be achieved through plot, and so in resisting what novels do, My Year of Rest and Relaxation ends up showing us what novels do. Being an antinovel turns out to be just another way of being a novel; in seeking to lose track of time, the novel at- tunes us to our being in time. Whenever I woke up, night or day, I’d shuffle through the bright marble foyer of my building and go up the block and around the corner where there was a bodega that never closed.1 For a long time I used to go to bed early.2 he first of these sentences begins Ottessa Moshfegh’s 2018 novelMy Year of Rest and Relaxation; the second, Proust’s In Search of Lost Time. More ac- T curately, the second sentence begins C. K. Scott Moncrieff’s translation of Proust, whose French reads, “Longtemps, je me suis couché de bonne heure.” D. J. Enright emends the translation to “I would go to bed”; Lydia Davis and Google Translate opt for “I went to bed.” What the translators famously wrestle with is how to render Proust’s ungrammatical combination of the completed action of the passé composé (“went to bed”) with a modifier (“long time”) that implies a re- peated, habitual, or everyday action. -

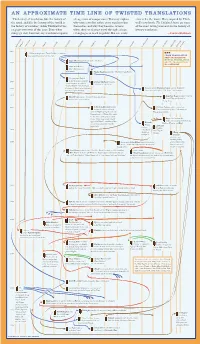

AN APPROXIMATE TIME LINE of TWISTED TRANSLATIONS “The History of Translation, Like the History of a Long Series of Compromises

AN APPROXIMATE TIME LINE OF TWISTED TRANSLATIONS “The history of translation, like the history of a long series of compromises. This may explain error is for the worse. Here, inspired by Thirl- the novel, and like the history of the world, is why some novelists refuse every translator but well’s new book, The Delighted States, are some the history of mistakes,” Adam Thirlwell writes themselves, and why they become anxious of the most vexing moments in the history of on page seventeen of this issue. Even when when their work must travel through a chain literary translation. things go well, however, any translation requires of languages to reach its public. But not every —Jascha Hoffman E N S E A N H I H H N N U N H H A C A S H S I C S A A H G A S I S N L I H H I I C I I I I B B L M S U D A A T C C N N S I T S N D U B A T G E R L S E R T L E N R R A D L R A E Z U N I R E E O O U P W I O A A C C C D E F F G P P P R S S Y Y 1490 KEY: A Valencian knight writes Tirant Lo Blanc in Catalan. CHAIN TRANSLATION It is finished by a friend after his death. SELF TRANSLATION Edgar Allan Poe publishes his poem “The Raven.” MUTUAL TRANSLATION 1850 GROUP TRANSLATION NO CATEGORY Lewis Carroll writes Alice’s Adventures in W onderland. -

1 NUMBER 96 FALL 2019-FALL 2020 in Memoriam

Virginia Woolf Miscellany NUMBER 96 FALL 2019-FALL 2020 Centennial Contemplations on Early Work (16) while Rosie Reynolds examines the numerous by Virginia Woolf and Leonard Woolf o o o o references to aunts in The Voyage Out and examines You can access issues of the the narrative function of Rachel’s aunt, Helen To observe the centennial of Virginia Woolf’s Virginia Woolf Miscellany Ambrose, exploring Helen’s perspective as well as early works, The Voyage Out, and Night and online on WordPress at the identity and self-revelation associated with the Day, and also Leonard Woolf’s The Village in the https://virginiawoolfmiscellany. emerging relationship between Rachel and fellow Jungle. I invited readers to adopt Nobel Laureate wordpress.com/ tourist Terence. Daniel Kahneman’s approach to problem-solving and decision making. In Thinking Fast and Slow, Virginia Woolf Miscellany: In her essay, Mine Özyurt Kılıç responds directly Kahneman distinguishes between fast thinking— Editorial Board and the Editors to the call with a “slow” reading of the production typically intuitive, impressionistic and reliant on See page 2 process that characterizes the work of Hogarth Press, associative memory—and the more deliberate, Editorial Policies particularly in contrast to the mechanized systems precise, detailed, and logical process he calls slow See page 6 from which it was distinguished. She draws upon “A thinking. Fast thinking is intuitive, impressionistic, y Mark on the Wall,” “Kew Gardens,” and “Modern and dependent upon associative memory. Slow – TABLE OF CONTENTS – Fiction,” to develop the notion and explore the thinking is deliberate, precise, detailed, and logical. -

CLAUDIA BAEZ Paintings After Proust

ART 3 109 Ingraham Street T 646 331 3162 Brooklyn NY 11237 www.art-3gallery.com FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CLAUDIA BAEZ, PAINTINGS after PROUST Curated by Anne Strauss October 8 – November 22, 2014 Opening: Wednesday, October 8, 6 - 9 PM Claudia Baez, PAINTINGS after PROUST “And as she played, of all Albertine’s multiple tresses I could see but a single heart-shaped loop of black hair dinging to the side of her ear like the bow of a Velasquez Infanta.”, 2014, oil on canvas, 18 x 24 in. (45.7 x 61 cm.) © Claudia Baez Courtesy of ART 3 gallery Brooklyn, NY, September 19, 2014 – ART 3 opened in Bushwick in May 2014 near Luhring Augustine with its Inaugural Exhibition covered by The New York Times T Magazine, Primer. ART 3 was created by Silas Shabelewska-von Morisse, formerly of Haunch of Venison and Helly Nahmad Gallery. In July 2014, Monika Fabijanska, former Director of the Polish Cultural Institute in New York, joined ART 3 as Co-Director in charge of curatorial program, museums and institutions. ART 3 presents CLAUDIA BAEZ, PAINTINGS after PROUST on view at ART 3 gallery, 109 Ingraham Street, Bushwick, Brooklyn, from October 8 to November 22, 2014, Tue-Sat 12-6 PM. The opening will take place on Wednesday, October 8, from 6-9 PM. “In PAINTINGS after PROUST, Baez offers us an innovative chapter in contemporary painting in ciphering her art via a modernist work of literature within a postmodernist framework. […] In Claudia Baez’s exhibition literary narrative is poetically refracted through painting and vice versa, which the painter reminds us with artistic verve and aplomb of the adage that every picture tells a story as well as the other way around”. -

Life and Works

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-02189-1 - Marcel Proust in Context Edited by Adam Watt Excerpt More information part i Life and works © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-02189-1 - Marcel Proust in Context Edited by Adam Watt Excerpt More information © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-02189-1 - Marcel Proust in Context Edited by Adam Watt Excerpt More information chapter 1 Life William C. Carter On 10 July 1901, Marcel Proust called on his friend Léon Yeatman in his law office and announced: ‘Today I’m thirty years old, and I’ve achieved nothing!’ (Corr, ii, 32). Yeatman must have protested, but Marcel had good reason to be discouraged. Nearly all his friends had established themselves as writers or launched other successful careers. Although he held university degrees in literature, philosophy and law, he had never entered a profession. He had stubbornly rejected the advice of his father, Dr Adrien Proust, one of France’s most distinguished physicians and scientists. After one of their heated discussions about his failure to choose a career, Marcel wrote: ‘My dearest papa ...I still believe that anything I do other than literature and philosophy will be just so much wasted time’ (Corr, i, 237). Dr Proust was a self-made man from the little town of Illiers. His fortune had greatly increased when he married Jeanne Weil, the daughter of a wealthy Jewish family. Proust adored his mother, who, though modest and discreet, quoted with ease from the classics in several languages. -

Memory, Time and Identity in the Novels of William Faulkner and Marcel Proust

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 2000 Memory, Time and Identity in the Novels of William Faulkner and Marcel Proust. John Stephen Larose Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Larose, John Stephen, "Memory, Time and Identity in the Novels of William Faulkner and Marcel Proust." (2000). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 7206. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/7206 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Bales 1970 1802768.Pdf

MARCEL PROUST AND REYNALDO HAHN II . \,_,1f' ,( Richard M~ Bales B.A. University of 11 Exeter, 1969 Submitted to the Department of ·French and Italian and the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the . requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Redacted Signature / ---instr.uct~-in_:_c arge V__/~-~ . /_CA .. __ . - /'1 _- -- .,, .' Redacted Signature rr the ./I.apartment 0 • R00105 7190b ] .,; ACKNOWLEDGMENT. I wish to express my sincerest thanks to Professor J. Theodore Johnson, Jr. for his kind help.in the preparation of this thesis, and especially for his having allowed me ready access ·to his vast Proustian bibliography and library. April 30, 1970. TABLE OF CONTENTS. Introduction •..•...............................•. 1 Chapter I: The Historical Picture ••••••••••••••• 6 Chapter II: Hahn in Proust•a Works ••••••••••••• 24 Chapter III: Proust's Correspondence with Hahn. 33 Chapter IV: Music for Proust ••••••••••••••••••• 5o Chapter V: :Music for Hahn.. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 61• Conclusion •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 76 Appendix I: Hahn's Life and Works •••••••••••••• Bo App~ndix II: Index to the more important com- posers (other than Hahn) in the Proust/ Hahn Correspondence •••••••••••••••••••••••• 83 Selective Bibliography••••••••••·••••••••••••••• 84 INTRODUCTION. The question of Proust and music .is a large one, for here, more than with perhaps any other author, the subject is particularly pregnant. Not only is there extended dis- cussion of music in Proust's works, but also the fictional Vinteuil in A la recherche du temps perdu is elevated to the rank .of an artistic "hero," a ."phare" in the Baudelairian sense. It is no accident that Vinteuil 1 s music is more of a revelation for the narrator than the works-of Bergotte the writer or Elstir the painter, for Proust virtually raised music to the highest art-foz,n, or, rather, it is th~ art-form which came closest to his own idea of "essence," the medium by.which souls can communicate. -

Paul Sollier: the First Clinical Neuropsychologist

Bogousslavsky J (ed): Following Charcot: A Forgotten History of Neurology and Psychiatry. Front Neurol Neurosci. Basel, Karger, 2011, vol 29, pp 105–114 Paul Sollier: The First Clinical Neuropsychologist Julien Bogousslavskya и Olivier Walusinskib aCenter for Brain and Nervous System Disorders, and Neurorehabilitation Services, Genolier Swiss Medical Network, Clinique Valmont, Montreux, Switzerland; bGeneral Practice, Brou, France Abstract novel In Search of Lost Time [1] (first published Paul Sollier (1861–1933) is perhaps the most unjustly for- in 1913; inaccurately translated into English as gotten follower of Jean-Martin Charcot. He studied with Remembrance of Things Past) emphasizes the Désiré Bourneville, Charcot’s second interne, and was con- importance of what he called ‘involuntary mem- sidered by Léon Daudet as the cleverest collaborator of Charcot, along with Joseph Babinski. Charcot assigned ory’, which is deeply associated with emotions. him the task of summarizing the theories on memory, In 1905–1906, Proust, who was psychological- which led to two major books, in 1892 and 1900, that ly exhausted, spent 6 weeks in a sanatorium un- anticipated several contemporary concepts by several der the care of Dr. Paul Sollier, a pupil of Charcot, decades. In 1905–1906, the novelist Marcel Proust spent whom the master of La Salpêtrière had asked (a 6 weeks with Sollier in his sanatorium at Boulogne-Billan- court, and it is now obvious that several of Proust’s ideas few years before his death) to synthesize the most on involuntary memories which appear inside In Search recent discoveries on memory [2, 3]. Sollier pub- of Lost Time (published 8 years later) had been inspired lished two major works on memory: Les Troubles by Sollier’s theories on the ‘surge of reminiscences’. -

Proust Booklet

Neville Jason NON- The Life FICTION and Work of BIOGRAPHY Marcel Proust Read by Neville Jason NA325212D 1 Reynaldo Hahn sings Offrande, 1909 8:00 2 Three fictional creative artists: 6:52 3 Proust’s episodes of ‘involuntary memory’ 3:53 4 The Franco-Prussian War 2:06 5 The birth of Marcel Proust, 10 January 1871 6:30 6 The goodnight kiss 11:47 7 Military service 5:50 8 The first short story 4:30 9 Influential drawing rooms 3:49 10 Comte Robert de Montesquiou-Fezensac 8:08 11 Reynaldo Hahn 13:43 12 Lucien Daudet 2:05 13 The Dreyfus Case 2:16 14 The Dreyfus Case (cont.) 3:53 15 Pleasures and Days 6:31 16 Jean Santeuil, the early, autobiographical novel 6:34 17 Anna de Noailles 3:30 18 Marcel Proust and John Ruskin 7:55 19 More work: Ruskin’s The Bible of Amiens 5:01 20 The move to 102 Boulevard Haussmann 5:12 2 21 Time Lost, Time Regained, involuntary memory 5:35 22 Alfred Agostinelli 7:36 23 Sergei Diaghilev, Jean Cocteau, Pablo Picasso 9:20 24 Looking for a publisher 8:23 25 The manuscript is delivered to Grasset 4:47 26 Proust and Agostinelli 4:47 27 Proust and Agostinelli (cont.) 1:27 28 The publication of Swann’s Way 9:57 29 The First World War begins, 3 August 1914 7:50 30 The year of 1915 7:56 31 The poet Paul Morand 3:07 32 Proust begins to go out again into the world 4:58 33 Proust changes publishers 6:00 34 The Armistice 2:34 35 Within a Budding Grove published in 1919, 6:22 36 The meeting with James Joyce 2:15 37 Proust and Music 6:30 38 The Guermantes Way Part II 4:09 39 Colette remembers 1:22 40 People and characters 7:47 41 Worsening health and death 7:07 Total time: 3:58:18 3 Neville Jason The Life and Work of Marcel Proust Few authors have attracted as many masterpiece, Remembrance of Things Past.