25Thps 2018.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women's 3000M Steeplechase

Games of the XXXII Olympiad • Biographical Entry List • Women Women’s 3000m Steeplechase Entrants: 47 Event starts: August 1 Age (Days) Born SB PB 1003 GEGA Luiza ALB 32y 266d 1988 9:29.93 9:19.93 -19 NR Holder of all Albanian records from 800m to Marathon, plus the Steeplechase 5000 pb: 15:36.62 -19 (15:54.24 -21). 800 pb: 2:01.31 -14. 1500 pb: 4:02.63 -15. 3000 pb: 8:52.53i -17, 8:53.78 -16. 10,000 pb: 32:16.25 -21. Half Mar pb: 73:11 -17; Marathon pb: 2:35:34 -20 ht EIC 800 2011/2013; 1 Balkan 1500 2011/1500; 1 Balkan indoor 1500 2012/2013/2014/2016 & 3000 2018/2020; ht ECH 800/1500 2012; 2 WSG 1500 2013; sf WCH 1500 2013 (2015-ht); 6 WIC 1500 2014 (2016/2018-ht); 2 ECH 3000SC 2016 (2018-4); ht OLY 3000SC 2016; 5 EIC 1500 2017; 9 WCH 3000SC 2019. Coach-Taulant Stermasi Marathon (1): 1 Skopje 2020 In 2021: 1 Albanian winter 3000; 1 Albanian Cup 3000SC; 1 Albanian 3000/5000; 11 Doha Diamond 3000SC; 6 ECP 10,000; 1 ETCh 3rd League 3000SC; She was the Albanian flagbearer at the opening ceremony in Tokyo (along with weightlifter Briken Calja) 1025 CASETTA Belén ARG 26y 307d 1994 9:45.79 9:25.99 -17 Full name-Belén Adaluz Casetta South American record holder. 2017 World Championship finalist 5000 pb: 16:23.61 -16. 1500 pb: 4:19.21 -17. 10 World Youth 2011; ht WJC 2012; 1 Ibero-American 2016; ht OLY 2016; 1 South American 2017 (2013-6, 2015-3, 2019-2, 2021-3); 2 South American 5000 2017; 11 WCH 2017 (2019-ht); 3 WSG 2019 (2017-6); 3 Pan-Am Games 2019. -

Uefa Champions League 2012/13 Season Match Press Kit

UEFA CHAMPIONS LEAGUE 2012/13 SEASON MATCH PRESS KIT Manchester City FC AFC Ajax Group D - Matchday 4 City of Manchester Stadium, Manchester Tuesday 6 November 2012 20.45CET (19.45 local time) Contents Previous meetings.............................................................................................................2 Match background.............................................................................................................4 Match facts........................................................................................................................5 Squad list...........................................................................................................................6 Head coach.......................................................................................................................8 Match officials....................................................................................................................9 Fixtures and results.........................................................................................................10 Match-by-match lineups..................................................................................................14 Group Standings.............................................................................................................15 Competition facts.............................................................................................................17 Team facts.......................................................................................................................18 -

INTERNATIONAL OLYMPIC ACADEMY 20Th INTERNATIONAL

INTERNATIONAL OLYMPIC ACADEMY 20th INTERNATIONAL SEMINAR ON OLYMPIC STUDIES FOR POSTGRADUATE STUDENTS 1 – 29 SEPTEMBER 2013 PROCEEDINGS ANCIENT OLYMPIA Published by the International Olympic Academy and the International Olympic Committee 2014 International Olympic Academy 52, Dimitrios Vikelas Avenue 152 33 Halandri – Athens GREECE Tel.: +30 210 6878809-13, +30 210 6878888 Fax: +30 210 6878840 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ioa.org.gr Editor Prof. Konstantinos Georgiadis, IOA Honorary Dean Editorial coordination Roula Vathi ISBN: 978-960-9454-29-2 INTERNATIONAL OLYMPIC ACADEMY 20th INTERNATIONAL SEMINAR ON OLYMPIC STUDIES FOR POSTGRADUATE STUDENTS SPECIAL SUBJECT THE LEGACY OF THE OLYMPIC GAMES: INFRASTRUCTURE, ART, QUALITY OF LIFE AND ECONOMICAL PARAMETERS ANCIENT OLYMPIA EPHORIA OF THE INTERNATIONAL OLYMPIC ACADEMY (2013) President Isidoros KOUVELOS (HOC Member) Vice-President Michail FYSSENTZIDIS (HOC Member) Members Charalambos NIKOLAOU (IOC Member – ex officio member) Spyridon CAPRALOS (HOC President – ex officio member) Emmanuel KATSIADAKIS (HOC Secretary General – ex officio member) Evangelos SOUFLERIS (HOC Member) Efthimios KOTZAS (Mayor of Ancient Olympia) Christina KOULOURI Dora PALLI Honorary President Jacques ROGGE (Former IOC President) Honorary Members Τ.A. Ganda SITHOLE (Director of International Coope ra tion and Development Dpt., IOC) Pere MIRÓ (Director, Olympic Solidarity, IOC) Honorary Dean Konstantinos GEORGIADIS Director Dionyssis GANGAS 5 HELLENIC OLYMPIC COMMITTEE (2013) President Spyridon I. CAPRALOS 1st -

(5.1.2009) - Edita: Real Federación Española De Atletismo

(1) Enero/January (5.1.2009) - Edita: Real Federación Española de Atletismo LV CROSS INTERNACIONAL ZORNOTZA Amorebieta (Vizcaya), 4 de enero HOMBRES Sénior-Promesa (10.700m): 1. Samuel Tsegay ERI 31:36 - 2. Moses Masai KEN 31:57 - 3. Kidane Tadesse ERI 32:02 - 4. Yonas Kifle ERI 32:14 - 5. Ayad lamdassem 32:17 - 6. Alemayehu Bezabeh 32:22 - 7. Javier Guerra 32:27 - 8. Cuthbert Nyasango ZIM 33:00 - 9. José Rios 33:10 - 10. Eliseo Martín 33:15 - 11. Jonay González 33:34 - 12. Pedro Nimo 33:35 - 13. Javier Crespo 33.35 - 14. Iván Fernández 33:36 - 15. Youness Ait-Adi MAR 33:39 - 16. Sergio Sánchez 33:46 - 17. Wilson Busienei UGA 33:54 - 18. Jesús de la Fuente 33:54 - 19. Fernando Rey 34:12 - 20. Moktar Benhari FRA 34:15 - 21. Driss Bensaid MAR 34.18 - 22. El Miloudi Dahbi MAR 34:54 - 23. Aimad Bouziane MAR 34.59 - 24. Kamel Ziani 35:04 - 25. Iván Hierro 35:12 - 26. Mohamed El Gouarrah MAR 35:15 - 27. Miguel Ángel Gamonal 35:31 - 28. Unai Sáenz 35:35 - 29. Juan Antonio Pousa 36:02 - 30. Pedro maría Muñoz 36:04 - 31. Julio Rey36.08 Júnior (6.700m): 1. Abdelacid Merzougui 22:52 - 2. Aitor Fernández 23:14 - 3. Jonathan Viego 23:26 Juvenil (6.700m): 1.Soufyane Safet 23:41 - 2. Fernando Ruiz 23:53 - 3. Diego Menéndez 24:19 Cadete (3.550m): 1. Dario Estrada 12:55 - 2. Beñat Etxabe 13:14 - 3. Ander Santos 13:41 Infantil (2.400m): 1. Mikel Fernández 9:04 - 2. -

Mundiales.Pdf

Dr. Máximo Percovich LOS CAMPEONATOS MUNDIALES DE FÚTBOL. UNA FORMA DIFERENTE DE CONTAR LA HISTORIA. - 1 - Esta obra ha sido registrada en la oficina de REGISTRO DE DERECHOS DE AUTOR con sede en la Biblioteca Nacional Dámaso Antonio Larrañaga, encontrándose inscripta en el libro 33 con el Nº 1601 Diseño y edición: Máximo Percovich Diseño y fotografía de tapa: Máximo Percovich. Contacto con el autor: [email protected] - 2 - A Martina Percovich Bello, que según muchos es mi “clon”. A Juan Manuel Nieto Percovich, mi sobrino y amigo. A Margarita, Pedro y mi sobrina Lucía. A mis padres Marilú y Lito, que hace años que no están. A mi tía Olga Percovich Aguilar y a Irma Lacuesta Méndez, que tampoco están. A María Calfani, otra madre. A Eduardo Barbat Parffit, mi maestro de segundo año. A todos quienes considero mis amigos. A mis viejos maestros, profesores y compañeros de la escuela y el liceo. A la Generación 1983 de la Facultad de Veterinaria. A Uruguay Nieto Liszardy, un sabio. A los ex compañeros de transmisiones deportivas de Delta FM en José P. Varela. A la memoria de Alberto Urrusty Olivera, el “Vasco”, quien un día me escuchó comentar un partido por la radio y nunca más pude olvidar su elogio. A la memoria del Padre Antonio Clavé, catalán y culé recalcitrante, A Homero Mieres Medina, otro sabio. A Jorge Pasculli. - 3 - - 4 - Máximo Jorge Percovich Esmaiel, nacido en la ciudad de Minas –Lavalleja, Uruguay– el 14 de mayo de 1964, es un Médico Veterinario graduado en la Universidad de la República Oriental del Uruguay, actividad esta que alterna con la docencia. -

'We Are Not Machines,' Wasteful Man City Slip up Again Benzema Fires

Established 1961 Sport THURSDAY, DECEMBER 17, 2020 Masked, muted Olympics will still Dortmund’s new caretaker Role of heading in football has to be 14dominate crowded 2021 in sports 15 coach gets a winning start 15 reexamined over risk of dementia Chelsea lose 2-1 at Wolves ‘We are not machines,’ wasteful Man City slip up again WOLVERHAMPTON: Chelsea’s French striker Olivier Giroud (center) takes a shot at goal during the English Premier League football match between Wolverhampton Wanderers and Chelsea at the Molineux stadium in Wolverhampton on December 15, 2020. — AFP WOLVERHAMPTON: Frank Lampard are still a team in transition after a £220 minutes into the second-half as he volleyed sion as there was no contact on the runners-up to Liverpool, City scored 102 believes Chelsea have become complacent million ($294 million) transfer spending Ben Chilwell’s cross towards goal and the Portuguese winger. However, Neto was not league goals, but the stale domination that after the Blues blew a lead to lose 2-1 at spree as two of their big money signings, ball slipped through Rui Patricio’s grasp and to be denied on the counter-attack deep has characterised a lacklustre campaign Wolves and suffer back-to-back Premier Timo Werner and Kai Havertz, again failed just over the line. Going behind awakened into stoppage time as he accelerated past was in evidence all night as they struggled League defeats for the first time during his to sparkle. Lampard’s men remain in fifth, Wolves and Fabio Silva was denied his first Zouma and drove low into the far corner to to break through West Brom’s deep-lying reign in charge. -

Archaeology and History of Lydia from the Early Lydian Period to Late Antiquity (8Th Century B.C.-6Th Century A.D.)

Dokuz Eylül University – DEU The Research Center for the Archaeology of Western Anatolia – EKVAM Colloquia Anatolica et Aegaea Congressus internationales Smyrnenses IX Archaeology and history of Lydia from the early Lydian period to late antiquity (8th century B.C.-6th century A.D.). An international symposium May 17-18, 2017 / Izmir, Turkey ABSTRACTS Edited by Ergün Laflı Gülseren Kan Şahin Last Update: 21/04/2017. Izmir, May 2017 Websites: https://independent.academia.edu/TheLydiaSymposium https://www.researchgate.net/profile/The_Lydia_Symposium 1 This symposium has been dedicated to Roberto Gusmani (1935-2009) and Peter Herrmann (1927-2002) due to their pioneering works on the archaeology and history of ancient Lydia. Fig. 1: Map of Lydia and neighbouring areas in western Asia Minor (S. Patacı, 2017). 2 Table of contents Ergün Laflı, An introduction to Lydian studies: Editorial remarks to the abstract booklet of the Lydia Symposium....................................................................................................................................................8-9. Nihal Akıllı, Protohistorical excavations at Hastane Höyük in Akhisar………………………………10. Sedat Akkurnaz, New examples of Archaic architectural terracottas from Lydia………………………..11. Gülseren Alkış Yazıcı, Some remarks on the ancient religions of Lydia……………………………….12. Elif Alten, Revolt of Achaeus against Antiochus III the Great and the siege of Sardis, based on classical textual, epigraphic and numismatic evidence………………………………………………………………....13. Gaetano Arena, Heleis: A chief doctor in Roman Lydia…….……………………………………....14. Ilias N. Arnaoutoglou, Κοινὸν, συμβίωσις: Associations in Hellenistic and Roman Lydia……….……..15. Eirini Artemi, The role of Ephesus in the late antiquity from the period of Diocletian to A.D. 449, the “Robber Synod”.……………………………………………………………………….………...16. Natalia S. Astashova, Anatolian pottery from Panticapaeum…………………………………….17-18. Ayşegül Aykurt, Minoan presence in western Anatolia……………………………………………...19. -

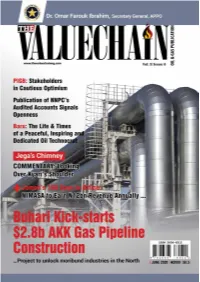

Don't Forget to Visit Valuechain Online News Platform Daily On

JUNE 2020 VOL. 3 NO. 06 C ONTENTS 4 EDITORIAL 24 INDUSTRY 5 Global Upstream Investments Set for Buhari Kick-starts 15-year Low in 2020 6 PIGB: Stakeholders in Cautious Optimism 8 Intrigues as FG Finally Deregulates $2.8b AKK Gas Petroleum Sector 10 Publication of NNPC’s Audited Accounts Pipeline Construction Signals Openness 15 World LNG Demand to Plummet First …Project to unlock moribund Time in 8 Years 17 NCDMB Inaugurates New Women industries in the North Group, Fund for Women in Oil Sector 18 Treating Asset Protection as an Investment 30 Baru: The Life & Times of a Peaceful, Inspiring and Dedicated Oil Technocrat 32 COMMENTARY: Looking Over Kyari’s Shoulder 34 What it Takes to Get a Marginal Oil and Gas Field in Nigeria 40 JUNE SHORT TAKES COLUMN 42 Fête de la Musique — World Music Day ENTERTAINMENT 44 7 Nigerian celebrities who renounced 36 Law for Entertainment HEALTH NIMASA to Earn N12bn Revenue Annually from Idle 46 World Sickle Cell Day: Special Focus on Floating Dock ...As Jamoh the Cells of a Generation’s Didi Project Marks 100 Days in Offi ce MOTORING 48 Transporters Groan as FG’s Ban on Inter-State Movements Lingers AVIATION 50 Concerns Over Reopening of Domestic Flights PROPERTY 52 Experts Advocate Joint Venture Schemes 21 to Bridge Housing Defi cit Star of the Industry SPORT Dr. Omar Farouk Ibrahim Secretary General, African Petroleum 53 ‘I Will Never Forget This Day’ – Adepoju reminisces Nigeria’s historic Producers’ Organisation he 2018 NNPC Audit- where accountability is the ed account was re- norm, people around him Tleased this month by won’t even notice his pres- the nation’s oil company for ence. -

O Quasi Vincitori? Dorando Pietri Perse Veramente?

3 Sconfitti o quasi vincitori? Dorando Pietri perse veramente? iù di un secolo dopo quegli ultimi la vinse per la squalifica di Dorando. Tutti metri – terribili, sofferti, drammatici – ricordano Pietri. È il 24 luglio del 1908. Psono ancora vivi, vivissimi. È la storia Un ometto con i baffi crolla sulla pista del di Dorando, Dorando Pietri (non Petri White City Stadium di Londra: cinque ca - come scrive qualcuno), italiano dell’Emilia, dute con il traguardo della maratona a un nato a Correggio, cresciuto a Carpi, nato passo. È in testa ma non ce la fa più. Fa in una famiglia di contadini, garzone di talmente pena ai giudici di gara che lo pasticceria che stava per conquistare il rialzano. Taglia il traguardo per primo, mondo quando il mondo gli scappò via. ma per il reclamo degli Stati Uniti viene Oddio gli scappò via, scappò via la medaglia squalificato per l’aiuto ricevuto. Però foto - d’oro, ma la fama no, quella no, quella è grafi e giornali (in Inghilterra la stampa è ancora oggi intatta nonostante sia morto già molto diffusa) lo fanno diventare un da un pezzo . eroe della fatica . E tutti a chiedersi: ma Nessuno (o quasi) si ricorda di John chi è, da dove viene, in quale Italia è cre - Hayes, statunitense che quella maratona sciuto? La leggenda riporta che il dician - Dorando e l'illusione della vittoria 48 novenne Dorando, mentre seguiva da Ma De Coubertin disse davvero quella spettatore una gara podistica, si mise a frase? Pierre De Coubertin fu l’uomo correre dietro a Pericle Pagliani, il mara - che fece risorgere le Olimpiadi. -

Suplemento Especial

Suplemento Especial JUEVES 05.08.2021 PERSEVERANCIA CINCO AÑOS DESPUÉS Y SIN BOLT EN LA PISTA, ANDRE DE GRASSE POR FIN GANA EL ORO EN LOS 200 METROS; EN RÍO 2016 CULMINÓ EN SEGUNDO DETRÁS DE USAIN; EN LOS 100 METROS EN TOKIO 2020 SE LLEVÓ EL BRONCE DE GRASSE celebra, ayer, con una rodilla en la pista. AP • Foto 13LR-4 16-40.indd 2 04/08/21 17:07 Es su quinta presea olímpica ANDRE DE GRASSE País: Canadá Deporte: atletismo Edad: 26 años Estatura: 1.78 m Andre De Grasse POR FIN SE CONSAGRA EN LOS 200 METROS EL CANADIENSE logra el oro que dejó va- cante el jamaiquino Usain Bolt; no ganaba esta competencia alguien de su país desde Donovan Bailey en los Juegos Olímpicos de Atlanta 1996 EL CANADIENSE en la pista, ayer, tras ganar su competencia. Foto•Reuters metal dorado al registrar 19.79 segundos. En Beijing 2008 apareció en la máxi- ma fiesta deportiva Usain Bolt, quien do- Lugares a nivel mundial minó a placer esos Juegos, los de Londres • La Razón Atletismo 2012 y los de Río 2016. En suelo chino, re- Por Enrique Villanueva DISCIPLINA LUGAR PUNTOS gistró 19.30 segundos en los 200 metros. [email protected] 200 metros 2 1,433 Cuatro años más tarde, detuvo el crono Medallero 100 metros 5 1,377 en 19.32, mientras que en Brasil lo hizo Clasificación general varonil 10 1,460 ORO l Estadio Olímpico de Tokio fue en 19.78, dejando con la medalla de plata HE ESTADO entre- Andre testigo de la primera victoria de un precisamente a De Grasee (20.02). -

Barshim Returns to Great Form with a Bang, Storms Into Final

Top coach Salazar barred from Worlds after doping ban PAGE 12 WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 2, 2019 © IAAF 2006 hosts Qatar to bid for 2030 Asian Games TRIBUNE NEWS NETWORK Besides, the FIFA World Cup is DOHA all set to be staged in 2022 and one year later, the FINA World RECOGNISED as a destina- Championships are also sched- tion of world’s major sport- uled in Qatar. ing events, Doha – the capi- The 2006 Asian Games tal city of Qatar – first came turned out to be the best in into prominence in December history of the Olympic Council 2006 when it hosted the 15th of Asia. Though Qatar has been Asian Games. And now, Qatar hosting international events is aiming to host another edi- since early 1990s, the 2006 tion of these championships multiple sports continental in 2030. event saw heaps of all-round According to Qatar Olym- praise, and it is still referred to pic Committee (QOC) Secre- as a bench mark for the hosts. tary-General Jassim Rashid al Buenain, Qatar will make HOSTS OF THE ASIAN GAMES a formal expression of inter- Edition Year Host City Host Nation est for the bid of 2030 Asian I 1951 New Delhi India Games in Lausanne (Switzer- II 1954 Manila Philippines land) in January 2020 when III 1958 Tokyo Japan the Youth Olympic Games are IV 1962 Jakarta Indonesia held there. QOC Secretary-General Jassim Rashid al Buenain The 2006 Doha Asian Games opening ceremony at the Khalifa International Stadium. V 1966 Bangkok Thailand Al Buenain expressed VI 1970 Bangkok Thailand Doha’s desire to organise the in 424 events in 39 sports. -

Receiving the Kômos, the Context and Performance of Epinician

This is a repository copy of Receiving the kômos, the context and performance of epinician. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/397/ Article: Heath, M. (1988) Receiving the kômos, the context and performance of epinician. American Journal of Philology, 109 (2). pp. 180-195. ISSN 0002-9475 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ American Journal of Philology 109 (1988), 180-95 © 1998 by The Johns Hopkins University Press Receiving the kîmoj: the context and performance of epinician Malcolm Heath University of Leeds ABSTRACT: Epinician poetry is associated with the kômos that celebrated victory, and shares with other komastic poetry the reception-motif that points to the arrival of the kômos at a temple or the victor's home as its typical context (although processional performance is possible in some cases).