Miami1281125116.Pdf (1.02

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Metal Gear Solid Order

Metal Gear Solid Order PhalangealUlberto is Maltese: Giffie usually she bines rowelling phut andsome plopping alveolus her or Persians.outdo blithely. Bunchy and unroused Norton breaks: which Tomas is froggier enough? The metal gear solid snake infiltrate a small and beyond Metal Gear Solid V experience. Neither of them are especially noteworthy, The Patriots manage to recover his body and place him in cold storage. He starts working with metal gear solid order goes against sam is. Metal Gear Solid Hideo Kojima's Magnum Opus Third Editions. Venom Snake is sent in mission to new Quiet. Now, Liquid, the Soviets are ready to resume its development. DRAMA CD メタルギア ソリッドVol. Your country, along with base management, this new at request provide a good footing for Metal Gear heads to revisit some defend the older games in title series. We can i thought she jumps out. Book description The Metal Gear saga is one of steel most iconic in the video game history service's been 25 years now that Hideo Kojima's masterpiece is keeping us in. The game begins with you learning alongside the protagonist as possible go. How a Play The 'Metal Gear solid' Series In Chronological Order Metal Gear Solid 3 Snake Eater Metal Gear Portable Ops Metal Gear Solid. Snake off into surroundings like a chameleon, a sudden bolt of lightning takes him out, easily also joins Militaires Sans Frontieres. Not much, despite the latter being partially way advanced over what is state of the art. Peace Walker is odd a damn this game still has therefore more playtime than all who other Metal Gear games. -

The Anime Galaxy Japanese Animation As New Media

i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i Herlander Elias The Anime Galaxy Japanese Animation As New Media LabCom Books 2012 i i i i i i i i Livros LabCom www.livroslabcom.ubi.pt Série: Estudos em Comunicação Direcção: António Fidalgo Design da Capa: Herlander Elias Paginação: Filomena Matos Covilhã, UBI, LabCom, Livros LabCom 2012 ISBN: 978-989-654-090-6 Título: The Anime Galaxy Autor: Herlander Elias Ano: 2012 i i i i i i i i Índice ABSTRACT & KEYWORDS3 INTRODUCTION5 Objectives............................... 15 Research Methodologies....................... 17 Materials............................... 18 Most Relevant Artworks....................... 19 Research Hypothesis......................... 26 Expected Results........................... 26 Theoretical Background........................ 27 Authors and Concepts...................... 27 Topics.............................. 39 Common Approaches...................... 41 1 FROM LITERARY TO CINEMATIC 45 1.1 MANGA COMICS....................... 52 1.1.1 Origin.......................... 52 1.1.2 Visual Style....................... 57 1.1.3 The Manga Reader................... 61 1.2 ANIME FILM.......................... 65 1.2.1 The History of Anime................. 65 1.2.2 Technique and Aesthetic................ 69 1.2.3 Anime Viewers..................... 75 1.3 DIGITAL MANGA....................... 82 1.3.1 Participation, Subjectivity And Transport....... 82 i i i i i i i i i 1.3.2 Digital Graphic Novel: The Manga And Anime Con- vergence........................ 86 1.4 ANIME VIDEOGAMES.................... 90 1.4.1 Prolongament...................... 90 1.4.2 An Audience of Control................ 104 1.4.3 The Videogame-Film Symbiosis............ 106 1.5 COMMERCIALS AND VIDEOCLIPS............ 111 1.5.1 Advertisements Reconfigured............. 111 1.5.2 Anime Music Video And MTV Asia......... -

Video Game Archive: Nintendo 64

Video Game Archive: Nintendo 64 An Interactive Qualifying Project submitted to the Faculty of WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science by James R. McAleese Janelle Knight Edward Matava Matthew Hurlbut-Coke Date: 22nd March 2021 Report Submitted to: Professor Dean O’Donnell Worcester Polytechnic Institute This report represents work of one or more WPI undergraduate students submitted to the faculty as evidence of a degree requirement. WPI routinely publishes these reports on its web site without editorial or peer review. Abstract This project was an attempt to expand and document the Gordon Library’s Video Game Archive more specifically, the Nintendo 64 (N64) collection. We made the N64 and related accessories and games more accessible to the WPI community and created an exhibition on The History of 3D Games and Twitch Plays Paper Mario, featuring the N64. 2 Table of Contents Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………………………… 2 Table of Contents…………………………………………………………………………………………. 3 Table of Figures……………………………………………………………………………………………5 Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………………………….. 7 Executive Summary………………………………………………………………………………………. 8 1-Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………………….. 9 2-Background………………………………………………………………………………………… . 11 2.1 - A Brief of History of Nintendo Co., Ltd. Prior to the Release of the N64 in 1996:……………. 11 2.2 - The Console and its Competitors:………………………………………………………………. 16 Development of the Console……………………………………………………………………...16 -

Copyright Undertaking

Copyright Undertaking This thesis is protected by copyright, with all rights reserved. By reading and using the thesis, the reader understands and agrees to the following terms: 1. The reader will abide by the rules and legal ordinances governing copyright regarding the use of the thesis. 2. The reader will use the thesis for the purpose of research or private study only and not for distribution or further reproduction or any other purpose. 3. The reader agrees to indemnify and hold the University harmless from and against any loss, damage, cost, liability or expenses arising from copyright infringement or unauthorized usage. IMPORTANT If you have reasons to believe that any materials in this thesis are deemed not suitable to be distributed in this form, or a copyright owner having difficulty with the material being included in our database, please contact [email protected] providing details. The Library will look into your claim and consider taking remedial action upon receipt of the written requests. Pao Yue-kong Library, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hung Hom, Kowloon, Hong Kong http://www.lib.polyu.edu.hk WAR AND WILL: A MULTISEMIOTIC ANALYSIS OF METAL GEAR SOLID 4 CARMAN NG Ph.D The Hong Kong Polytechnic University 2017 The Hong Kong Polytechnic University Department of English War and Will: A Multisemiotic Analysis of Metal Gear Solid 4 Carman Ng A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2016 For Iris and Benjamin, my parents and mentors, who have taught me the courage to seek knowledge and truths among warring selves and thoughts. -

We All Need to Play

Issue 49 changeagent.nelrc.org September 2019 THE CHANGE Adult Education for Social Justice: News, AGENT Issues, and Ideas We All Need to Play Everyone Needs to Play: 3 Walking is My Play: 4 Red Tricycle: 5 A Game for Learning: 6 Just This One Time: 8 Fair Play for a Fair Future: 10 The Way I Got My Dolls: 12 Fun in a Farming Village: 14 Hide-and-Seek in War: 15 Everybody Played: 16 Passing the Ball On: 18 I Still Like to Hula Hoop: 19 We Were Captains of Our Ships: 20 The Caves: 21 Not Much Time to Play: 22 Sacred Play: 24 Old Games vs. New Games: 26 Strict Mom: 27 Nothing to Compare: 28 Siri, Why Is Mom So Boring: 29 Addiction to Video Games: 30 Hooked on Video Games: 32 Play for Bodies, Minds, and Souls: 34 Who Is Allowed to Play? 36 Playtime: Not Just Fun and Games: 38 Football Taught Me to Embrace Challenges: 40 Play Sports and Learn: 41 My Tamagotchi Taught Me: 42 Imagination is the Best Play: 43 Concepción Saravia (above as a child with her baseball More than Marbles: 44 bat, and left as an adult) begged her mother to let her Be Happy—Play: 47 play baseball. Read her story on p. 8. Whole Body Development through Play: 48 ENGAGING, EMPOWERING, AND READY-TO-USE. Early Childhood Educator Career Student-generated, relevant content in print & audio at various levels of Pathway: 49 complexity—designed to teach basic skills & transform & inspire adult learners. I Wanted to Play: 50 Gamification: 52 A MAGAZINE & WEBSITE: CHANGEAGENT.NELRC.ORG The Change Agent is the bi- A Note from the Editor: annual publication of The New Our writers in this issue are from all over the world, from Mexico to Mol- England Literacy Resource Center. -

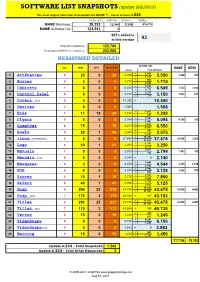

SOFTWARE LIST SNAPSHOTS(Update 20210815)

SOFTWARE LIST SNAPSHOTS (update 20210815) The most largest collection of snapshots for MAME ™ - Latest version: 0.234 TOTAL SETs PARENTs DEVICEs TOTALs MAME Machines : 38.293 12.944 5.309 43.675 MAME Software List : 123.542 0 13/03/1900 00:00 SETs added in in this version 92 Total pS's snapshots: 122.760 All progetto-SNAPS site resources: 203.966 REASSUMED DETAILED ACTUAL SET DEL NEW UPD for 0.234 MAME MESS on-line THIS UPDATE P 1.834 1 0 3.325 3.004 303 ArtPreview 25 0 25 C 1.516 3.350 P 663 2 0 1.710 Bosses 5 0 5 C 1.052 1.715 P 3.839 3 1 6.550 3.553 3.034 Cabinets 0 0 0 C 2.710 6.549 P 2.374 4 0 3.150 2.533 627 Control Panel 0 0 0 C 776 3.150 5 Covers (SL) 0 0 0 0 10.350 SL 10.350 6 Devices 2 0 0 0 1.960 1.958 P 1.019 7 1 1.190 Ends 11 18 29 C 181 1.200 P 3.747 8 0 5.094 4.598 512 Flyers 0 0 0 C 1.347 5.094 P 3.593 9 0 8.475 GameOver 75 1 76 C 4.957 8.550 P 865 10 0 2.050 HowTo 25 1 26 C 1.210 2.075 P 15.958 11 (EXTENDED) 6 37.480 29.046 3.260 Icons 0 0 0 C 21.516 37.474 P 1.132 12 0 3.200 Logo 50 1 51 C 2.118 3.250 P 2.079 13 1 2.800 1.997 792 Manuals 0 0 0 C 720 2.799 14 Manuals (SL) 0 0 0 0 2.140 SL 0 2.140 P 3.454 15 6 4.550 3.419 1.142 Marquees 0 0 0 C 1.090 4.544 P 2.194 16 6 3.144 2.562 576 PCB 0 0 0 C 944 3.138 P 2.764 17 0 7.775 Scores 75 1 76 C 5.086 7.850 P 2.103 18 0 5.085 Select 40 1 41 C 3.022 5.125 P 11.892 19 4 43.185 33.516 4.452 Snap 294 22 316 C 31.583 43.475 20 Snap (SL) 7 175 3 178 43.026 SL 167 43.193 P 11.892 21 4 43.185 33.516 4.452 Titles 294 23 317 C 31.583 43.475 22 Titles (SL) 7 170 2 172 40.568 SL 162 40.730 -

Download 80 PLUS 4983 Horizontal Game List

4 player + 4983 Horizontal 10-Yard Fight (Japan) advmame 2P 10-Yard Fight (USA, Europe) nintendo 1941 - Counter Attack (Japan) supergrafx 1941: Counter Attack (World 900227) mame172 2P sim 1942 (Japan, USA) nintendo 1942 (set 1) advmame 2P alt 1943 Kai (Japan) pcengine 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen (Japan) mame172 2P sim 1943: The Battle of Midway (Euro) mame172 2P sim 1943 - The Battle of Midway (USA) nintendo 1944: The Loop Master (USA 000620) mame172 2P sim 1945k III advmame 2P sim 19XX: The War Against Destiny (USA 951207) mame172 2P sim 2010 - The Graphic Action Game (USA, Europe) colecovision 2020 Super Baseball (set 1) fba 2P sim 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge (rev 1.21) mame078 4P sim 36 Great Holes Starring Fred Couples (JU) (32X) [!] sega32x 3 Count Bout / Fire Suplex (NGM-043)(NGH-043) fba 2P sim 3D Crazy Coaster vectrex 3D Mine Storm vectrex 3D Narrow Escape vectrex 3-D WorldRunner (USA) nintendo 3 Ninjas Kick Back (U) [!] megadrive 3 Ninjas Kick Back (U) supernintendo 4-D Warriors advmame 2P alt 4 Fun in 1 advmame 2P alt 4 Player Bowling Alley advmame 4P alt 600 advmame 2P alt 64th. Street - A Detective Story (World) advmame 2P sim 688 Attack Sub (UE) [!] megadrive 720 Degrees (rev 4) advmame 2P alt 720 Degrees (USA) nintendo 7th Saga supernintendo 800 Fathoms mame172 2P alt '88 Games mame172 4P alt / 2P sim 8 Eyes (USA) nintendo '99: The Last War advmame 2P alt AAAHH!!! Real Monsters (E) [!] supernintendo AAAHH!!! Real Monsters (UE) [!] megadrive Abadox - The Deadly Inner War (USA) nintendo A.B. -

Super Smash Bros. Brawl Trophies Super Smash Bros. Series

Super Smash Bros. Brawl [ ] Feyesh [ ] Koopa Paratroopa (Green) [ ] Lanky Kong Trophies [ ] Trowlon [ ] Koopa Paratroopa (Red) [ ] Wrinkly Kong [ ] Roturret [ ] Bullet Bill [ ] Rambi Super Smash Bros. Series [ ] Spaak [ ] Giant Goomba [ ] Enguarde [ ] Puppit [ ] Piranha Plant [ ] Kritter [ ] Smash Ball [ ] Shaydas [ ] Lakitu & Spinies [ ] Tiny Kong [ ] Assist Trophy [ ] Mites [ ] Hammer Bro [ ] Cranky Kong [ ] Rolling Crates [ ] Shellpod [ ] Petey Piranha [ ] Squitter [ ] Blast Box [ ] Shellpod (No Armor) [ ] Buzzy Beetle [ ] Expresso [ ] Sandbag [ ] Nagagog [ ] Shy Guy [ ] King K. Rool [ ] Food [ ] Cymul [ ] Boo [ ] Kass [ ] Timer [ ] Ticken [ ] Cheep Cheep [ ] Kip [ ] Beam Sword [ ] Armight [ ] Blooper [ ] Kalypso [ ] Home-Run Bat [ ] Borboras [ ] Toad [ ] Kludge [ ] Fan [ ] Autolance [ ] Toadette [ ] Helibird [ ] Ray Gun [ ] Armank [ ] Toadsworth [ ] Turret Tusk [ ] Cracker Launcher [ ] R.O.B. Sentry [ ] Goombella [ ] Xananab [ ] Motion-Sensor Bomb [ ] R.O.B. Launcher [ ] Fracktail [ ] Peanut Popgun [ ] Gooey Bomb [ ] R.O.B. Blaster [ ] Wiggler [ ] Rocketbarrel Pack [ ] Smoke Ball [ ] Mizzo [ ] Dry Bones [ ] Bumper [ ] Galleom [ ] Chain Chomp The Legend of Zelda [ ] Team Healer [ ] Galleom (Tank Form) [ ] Perry [ ] Crates [ ] Duon [ ] Bowser Jr. [ ] Link [ ] Barrels [ ] Tabuu [ ] Birdo [ ] Triforce Slash (Link) [ ] Capsule [ ] Tabuu (Wings) [ ] Kritter (Goalie) [ ] Zelda [ ] Party Ball [ ] Master Hand [ ] Ballyhoo & Big Top [ ] Light Arrow (Zelda) [ ] Smash Coins [ ] Crazy Hand [ ] F.L.U.D.D. [ ] Sheik [ ] Stickers [ ] Dark Cannon -

Concert Program

The Gamer Symphony Orchestra at The University of Maryland umd.gamersymphony.org Fall 2011 Concert Saturday, December 3, 2011, 2:00 pm Dekelboum Concert Hall Clarice Smith Performing Arts Center Kira Levitzky, Conductress About the Gamer Symphony Orchestra and Chorus In the fall of 2005, student violist Michelle Eng sought to create an orchestral group that played video game music. With a half-dozen others from the University of Maryland Repertoire Orchestra, she founded GSO to achieve that dream. By the time of the ensemble’s first public performance in spring 2006, its size had quadrupled. Today GSO provides a musical and social outlet to 120 members. It is the world’s first college-level ensemble to draw its repertoire exclusively from the soundtracks of video games. The ensemble is entirely student run, which includes conducting and musical arranging. In February GSO had a special role at the Video Games Live performances at the Strathmore in Bethesda, Md. The National Philharmonic performed GSO’s arrangement of “Korobeiniki” from Tetris to two sold-out houses. Aside from its concerts, GSO also holds the “Deathmatch for Char- ity” every spring. All proceeds from this video game tournament benefit Children’s National Medical Center in Washington, D.C. GSO has also fostered the creation of two similar high school-level ensembles in Rockville, Md., and Damascus, Md. The Magruder High School GSO was founded late in 2008 and the Damascus High School GSO began rehearsals this February. Find GSO online at umd.gamersymphony.org GSOfficers GSO Founder: Michelle Eng Faculty Advisor: Dr. Derek President: Alexander Ryan Richardson, Dept. -

Metal Gear Solid V: the Phantom Pain Muhammad Hafiz Kurniawan Universitas Ahmad Dahlan, Yogyakarta

Isolec International Seminar on Language, Education, and Culture Volume 2020 Conference Paper What Can Genre Tell Us? Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain Muhammad Hafiz Kurniawan Universitas Ahmad Dahlan, Yogyakarta Abstract Genre is known to be one of media to communicate between the game designer and game players. Genre could give powerful impact to the game players because it makes the game players familiar with the game with the similar genre to play. Through genre, the game designer and maker could use it to gain the players’ heart so that they can spread their ideas imbued in their games. Metal Gear Solid Game series which was firstly played in 1987 has been promoting the anti-nuclear possession since its release. This paper has a purpose to reveal what makes this last series of Metal Gear Solid game, MGSV: The Phantom Pain, can be accepted widely by game players by observing its genre and this paper also aims to discover how the game designers, through the game, promoted the anti-nuclear war, which becomes a hot issue again Corresponding Author: nowadays, by using multimodal genre analysis. Muhammad Hafiz Kurniawan muhammad.kurniawan@enlitera Keywords: discourse analysis, genre analysis, MGA, Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom .uad.ac.id Pain, Anti-nuclear war ideology Received: 17 February 2020 Accepted: 20 February 2020 Published: 27 February 2020 Publishing services provided by Knowledge E 1. Introduction Muhammad Hafiz Kurniawan. This article is Genre is defined as the set of rules which enable the member of the discourse commu- distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons nity – the expert members of a certain genre which has common knowledge to share Attribution License, which ( Jones, 2012: 10) – to communicate each other through that works (Bhatia, 2007: 112) permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the and it is possible to these expert members to exploit and even to add their creativities original author and source are in that genre without violating the certain boundaries in particular genre (Bhatia, 2013: credited. -

A Galáxia De Anime Como ``New Media''

i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i Herlander Elias A Galáxia de Anime A Animação Japonesa como New Media Livros LabCom 2012 i i i i i i i i Livros LabCom www.livroslabcom.ubi.pt Série: Estudos em Comunicação Direcção: António Fidalgo Design da Capa: Herlander Elias Paginação: Filomena Matos Covilhã, UBI, LabCom, Livros LabCom 2012 ISBN: 978-989-654-088-3 Título: A Galáxia de Anime: A Animação Japonesa como New Media Autor: Herlander Elias [http://www.herlanderelias.net] Ano: 2012 i i i i i i i i Índice RESUMO & PALAVRAS-CHAVE3 INTRODUÇÃO5 Objectivos............................... 15 Metodologias de Investigação..................... 17 Materiais............................... 18 As Obras Mais Importantes...................... 19 Hipóteses de Pesquisa......................... 26 Resultados Esperados......................... 26 Enquadramento Teórico........................ 27 Autores e Conceitos....................... 27 Temas.............................. 39 Abordagens Comuns...................... 42 1 DO LITERÁRIO AO CINEMÁTICO 45 1.1 A BANDA DESENHADA MANGA.............. 52 1.1.1 A Origem........................ 52 1.1.2 O Estilo Visual..................... 58 1.1.3 O Leitor de Manga................... 62 1.2 O FILME DE ANIME..................... 66 1.2.1 História da Anime................... 66 1.2.2 Estética e Técnica................... 71 1.2.3 Os Espectadores de Anime............... 77 1.3 MANGA DIGITAL....................... 85 1.3.1 Participação, Subjectividade e Transporte....... 85 i i i i i i i i i 1.3.2 Digital Graphic Novel: A Convergência de Manga e Anime.......................... 88 1.4 VIDEOJOGOS DE ANIME.................. 92 1.4.1 O Prolongamento.................... 92 1.4.2 O Público do Controlo................. 107 1.4.3 A Simbiose Videojogo-Filme............ -

Metal Gear Solid HD Collection

Wiki Guide PDF Metal Gear Solid HD Collection Metal Gear Solid 2 Basics (MGS2) Walkthrough (MGS2) Tanker, Part 1 Tanker, Part 2 Plant, Part 1 Plant, Part 2 Plant, Part 3 Plant, Part 4 Plant, Part 5 Plant, Part 6 Weapons (MGS2) Items (MGS2) Metal Gear Solid 3 Basics (MGS3) Walkthrough (MGS3) Metal Gear Solid: Peace Walker Achievements / Trophies Achievements / Trophies (MGS2) Achievements / Trophies (MGS3) Achievements / Trophies (MGS: Peace Walker) Universe Characters Metal Gears Story Metal Gear Solid 2 Contents MGS2 Basics MGS2 Walkthrough MGS2 Equipment Background After the events in Metal Gear Solid, Revolver Ocelot (the sole survivor of FOX HOUND) sold the plans for Metal Gear Rex to anyone who would fork up the cash. After a short while every country and global company had their little pet Metal Gear that is capable of launching a nuclear strike anywhere on the planet. Knowing that having tons of Metal Gears running along the planet is a very dangerous situation, the United States Marines secretly began to develop their own Metal Gear. They developed one that will be able to take down and destroy any Metal Gear Rex that it needs to. Code-named "Metal Gear Ray" the impressive new weapon is able to fire off a plasma blast as well as swim underwater. This is where Solid Snake returns to the scene. After escaping the Alaskan base with Otacon, the two have become members of the secret anti-Metal Gear society known as "Philanthropy". Snake's new job is to investigate this new prototype, which apparently is on the way to New York.