I Social Conflict and Peace-Building

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Culturally Relevant Teacher Education: a Canadian Inner-City Case

Culturally Relevant Teacher Education: A Canadian Inner-City Case Rick Hesch winnipeg, manitoba This case study of an inner-city teacher education program documents the tensions at work on a social reconstructionist academic staff attempting to produce a culturally relevant teacher education program. Cultural relevance here includes three features: supporting academic achievement, maintaining cultural competence, and developing critical consciousness. All interests converge on the need to produce academically and technically competent teachers. Beyond this, the staff remain mindful of the dominant social and educational context within which they work and at the same time attempt to meet the longer-term interests of their students and culturally different inner-city communities. The possibilities for success have lessened in the political economy of the 1990s, but the study provides concrete instances of developing a culturally relevant teacher education program. Cette étude de cas portant sur un programme de formation à l’enseignement dans des écoles de quartiers défavorisés décrit les tensions au sein du personnel enseignant cher- chant à produire un programme de formation des maîtres culturellement significatif. Trois éléments définissent la pertinence culturelle d’un programme : il doit promouvoir la réussite scolaire, être adapté à la culture et développer une pensée critique. Tous les intervenants s’accordent sur la nécessité de produire des enseignants compétents. Cela dit, le personnel doit garder à l’esprit le contexte éducatif et social dominant dans lequel il travaille tout en essayant de tenir compte des intérêts à long terme des élèves et de diverses communautés culturelles implantées dans des quartiers défavorisés. L’étude fournit des exemples concrets de la marche à suivre pour élaborer un programme de formation à l’enseignement culturellement significatif. -

Winnipeg Downtown Profile

WINNIPEG DOWNTOWN PROFILE A Special Report on Demographic and Housing Market Factors in Winnipeg’s Downtown IUS SPECIAL REPORT JULY-2017 Institute of Urban Studies 599 Portage Avenue, Winnipeg P: 204 982-1140 F: 204 943-4695 E: [email protected] Mailing Address: 515 Portage Avenue, Winnipeg, Manitoba, R3B 2E9 Author: Scott McCullough, Jino Distasio, Ryan Shirtliffe Data & GIS: Ryan Shirtliffe Research: Ryan Shirtliffe, Scott McCullough Supporting Research: Brad Muller, CentreVenture The Institute of Urban Studies is an independent research arm of the University of Winnipeg. Since 1969, the IUS has been both an academic and an applied research centre, committed to examining urban development issues in a broad, non-partisan manner. The Institute examines inner city, environmental, Aboriginal and community development issues. In addition to its ongoing involvement in research, IUS brings in visiting scholars, hosts workshops, seminars and conferences, and acts in partnership with other organizations in the community to effect positive change. Introduction This study undertakes an analysis of demographic and housing market factors that may influence the need for incentives in the downtown Winnipeg housing market. This report informs CentreVenture’s proposed “10 Year Housing Evaluation” and helps to address the proposed question, “What price do new downtown housing projects need to achieve to encourage more people to move downtown?” To accomplish this, the following have been undertaken: 1. A Demographic Analysis of current downtown Winnipeg residents with a comparison to Winnipeg medians, 2. A Rental Market Analysis comparing downtown rates to Winnipeg averages, as well as changing rental rates in the downtown from Census data, 3. -

Ii WOODY GUTHRIE

ii WOODY GUTHRIE THIS COLLECTION PRESENTS FOR THE FIRST TIME the full range of material Woody Guthrie recorded for the United States government, both in song and the spoken word. This publication brings together two significant bodies of work – the songs and stories he recorded for the Library of Congress, and the material he created when hired to write songs for the Bonneville Power Administration. There have been records released in the past of the Library of Congress recordings, but this collection is the first time that the complete and unedited Library of Congress sessions have been released. The songs from those recording dates have been available in the past – notably from Elektra and from Rounder – but we offer here the full body of work, including the hours of Woody Guthrie talking and telling his story. TO THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS AND BPA RECORDINGS, we have also added material which Woody recorded for governmental or quasi-governmental efforts – some songs and two 15-minute radio dramas for the Office of War Information during the Second World War and another drama offered to public health agencies to fight the spread of venereal disease. WOODY GUTHRIE AMERICA N RADICA L PATRIOT by Bill Nowlin Front cover photo: marjorie mazia and woody guthrie in east st. louis, missouri. july 29, 1945. Inside front and inside back cover photo: woody, “oregon somewhere” on the coast in oregon. this is the only known photograph of woody guthrie during the time he spent touring with the bpa. ℗ 2013 Woody Guthrie Foundation. © 2013 Rounder Records. Under exclusive license to Rounder Records. -

Track Artist Album Format Ref # Titirangi Folk Music Club

Titirangi Folk Music Club - Library Tracks List Track Artist Album Format Ref # 12 Bar Blues Bron Ault-Connell Bron Ault-Connell CD B-CD00126 12 Gates Bruce Hall Sounds Of Titirangi 1982 - 1995 CD V-CD00031 The 12th Day of July Various Artists Loyalist Prisoners Aid - UDA Vinyl LP V-VB00090 1-800-799-7233 [Live] Saffire - the Uppity Blues Women Live & Uppity CD S-CD00074 1891 Bushwackers Faces in the Street Vinyl LP B-VN00057 1913 Massacre Ramblin' Jack Elliot The Essential Ramblin' Jack Elliot Vinyl LP R-VA00014 1913 Massacre Ramblin' Jack Elliot The Greatest Songs of Woodie Guthrie Vinyl LP X W-VA00018 The 23rd of June Danny Spooner & Gordon McIntyre Revived & Relieved! Vinyl LP D-VN00020 The 23rd Of June the Clancy Brothers & Tommy Makem Hearty And Hellish Vinyl LP C-VB00020 3 Morris Tunes - Wheatley Processional / Twenty-ninth of May George Deacon & Marion Ross Sweet William's Ghost Vinyl LP G-VB00033 3/4 and 6/8 Time Pete Seeger How to play the Old Time Banjo Vinyl LP P-VA00009 30 Years Ago Various Artists & Lindsey Baker Hamilton Acoustic Music Club CD H-CD00067 35 Below Lorina Harding Lucky Damn Woman CD L-CD00004 4th July James RAy James RAy - Live At TFMC - October 2003 CD - TFMC J-CN00197 500 Miles Peter Paul & Mary In Concert Vinyl LP X P-VA00145 500 Miles Peter Paul & Mary Best of Peter, Paul & Mary: Ten Years Together Vinyl LP P-VA00101 500 Miles The Kingston Trio Greatest Hits Vinyl LP K-VA00124 70 Miles Pete Seeger God Bless the Grass Vinyl LP S-VA00042 900 Miles Cisco Houston The Greatest Songs of Woodie Guthrie Vinyl LP -

Jewish-Israeli Identity in Naomi Shemer's Songs: Central

JEWISH-ISRAELI IDENTITY IN NAOMI SHEMER’S SONGS: CENTRAL VALUES OF THE JEWISH-ISRAELI IMAGINED COMMUNITY La identidad judía israelí en las canciones de Naomi Shemer: principales valores de la «comunidad imaginada» judía israelí MICHAEL GADISH Universidad de Barcelona BIBLID [1696-585X (2009) 58; 41-85] Resumen: El presente artículo analiza una selección de las canciones más populares de la prolífica cantautora israelí Naomi Shemer, con el objetivo de reconocer y señalar las pautas de pensamiento más repetidas en sus canciones. La primera parte del artículo expone brevemente la importancia de las canciones de Naomi Shemer para la identidad Judeo-Israelí y argumenta por qué las pautas de pensamiento que encontramos en ellas se pueden considerar relevantes para la comprensión de la identidad Judeo-Israelí en general. El análisis de las letras seleccionadas expone algunos elementos contradictorios en el núcleo de la identidad Judeo-Israelí que las canciones de Naomi Shemer representan. Abstract: The following article analyzes the lyrics of a selection of the most popular songs by the prolific Jewish-Israeli songwriter Naomi Shemer, in order to recognize and highlight the most repeated patterns of thought in them. The first part of the article briefly explains the importance of Naomi Shemer’s songs for Jewish-Israeli identity and why the patterns of thought found in them can be considered relevant for understanding Jewish- Israeli identity in general. The analysis of the selected lyrics reveals some contradictory elements at the core of the Jewish-Israeli identity as represented by Naomi Shemer’s songs. Palabras clave: Naomi Shemer, canciones, folclore, ritual, cantautor hebreo, Judío-Israelí, sionismo, comunidad imaginada, identidad, nacionalismo. -

Volume 3: Population Groups and Ethnic Origins

Ethnicity SEriES A Demographic Portrait of Manitoba Volume 3 Population Groups and Ethnic Origins Sources: Statistics Canada. 2001 and 2006 Censuses – 20% Sample Data Publication developed by: Statistics Canada information is used with the permission of Statistics Canada. Manitoba Immigration and Users are forbidden to copy the data and redisseminate them, in an original or Multiculturalism modified form, for commercial purposes, without permission from Statistics And supported by: Canada. Information on the availability of the wide range of data from Statistics Canada can be obtained from Statistics Canada’s Regional Offices, its World Wide Citizenship and Immigration Canada Web site at www.statcan.gc.ca, and its toll-free access number 1-800-263-1136. Contents Introduction 2 Canada’s Population Groups 3 manitoba’s Population Groups 4 ethnic origins 5 manitoba Regions 8 Central Region 10 Eastern Region 13 Interlake Region 16 Norman Region 19 Parklands Region 22 Western Region 25 Winnipeg Region 28 Winnipeg Community Areas 32 Assiniboine South 34 Downtown 36 Fort Garry 38 Inkster 40 Point Douglas 42 River East 44 River Heights 46 Seven Oaks 48 St. Boniface 50 St. James 52 St. Vital 54 Transcona 56 Vol. 3 Population Groups and Ethnic Origins 1 Introduction Throughout history, generations of The ethnicity series is made up of three volumes: immigrants have arrived in Manitoba to start a new life. Their presence is 1. Foreign-born Population celebrated in our communities. Many This volume presents the population by country of birth. It focuses on the new immigrants, and a large number foreign-born population and its recent regional distribution across Manitoba. -

MAWA Urban Aboriginal Advisory Committee Final Report, 2005

Mentoring Artists for Women’s Art, MAWA Urban Aboriginal Advisory Committee Final Report 2005 Final report prepared by Cheyenne Henry May 2005 Table of Contents Preface 3 Introduction 5 Report Objectives 8 Report Summary 9 Obstacles Faced by Aboriginal Artists in the Pursuit of Their Professional Practices 13 Obstacles Making Participation in MAWA Programs Difficult for Aboriginal Women Artists 26 Recommendations to Increase Participation of Aboriginal Women Artists in MAWA Programs 28 Ways MAWA can Facilitate Participation by Aboriginal Artists in Existing Programs 34 New Programs or Partnerships that MAWA Could Develop to Support Aboriginal Women Artists 43 Action Plan 52 Proposed New Position 52 Outcomes of Proposed Position 54 1 Personal Note 55 Urban Aboriginal Advisory Committee Biographies 57 2 Preface In 2003 Mentoring Artists for Women’s Art (MAWA) undertook a comprehensive assessment of the organization’s programs and resources. This process was timely given that 2004 would mark MAWA’s 20th year in operation. During our history many changes have taken place, but the driving philosophy to encourage and support the intellectual and creative development of women in the visual arts by providing an ongoing forum for education and critical dialogue has remained stable. At the core of our programs are the mentorships for which MAWA is celebrated well beyond our borders. MAWA is the only organization in Canada to offer a range of mentorship programs to women in the visual arts. These programs range from weekend workshops to year-long mentorships, with much in-between. The 2003 assessment determined that MAWA was doing many things right. -

Singing in ‘The Peg’: the Dynamics of Winnipeg Singing Cultures During the 20Th Century

Singing in ‘The Peg’: The Dynamics of Winnipeg Singing Cultures During the 20th Century Muriel Louise Smith Doctor of Philosophy University of York Music September 2015 This thesis is dedicated to my parents, William Moore (1910-1982) Ann Moore (1916-2011) who inspired, demanded excellence, and loved me. 2 Abstract The research begins by establishing Winnipeg, as a city comprised of many different European immigrant communities where the dominant British-Canadian culture reflected the Canadian national consciousness of the early 20th century. After an outline of early musical life in the city, four case studies demonstrate how the solo vocal and choral culture in Winnipeg represents a realization of the constitutive, continuously forming and mutable relationships between peoples of differing identities. In all of these case studies, I investigate how this culture has been shaped by social and political actions through transnational connections over the 20th century. The first two case studies are underpinned by the theories of cultural capital and gender. The first focuses on the Women’s Musical Club of Winnipeg (1900-1920s), an elite group of Brito-Canadian women who shaped the reception of high art singing among their peers primarily through their American connections. The second investigates the Men’s Musical Club of Winnipeg (1920s-1950s), a dynamic group of businessmen and musicians who sought to reinforce Brito-Canadian cultural supremacy by developing a choral culture and establishing a music competition festival based on British models and enforced by British musical associations. The third and fourth case studies are examined through the lens of diaspora and identity, underpinned by social capital. -

Owen, David Dir. "Searching for the Ghost of Tom Joad&Q

This is the published version of the article: Bayo Ibars, Anna Ma.; Owen, David dir. "Searching for the ghost of Tom Joad" : resurrecting Steinbeck’s gaze. 2011. 83 p. This version is available at https://ddd.uab.cat/record/102073 under the terms of the license MA Dissertation “Searching for the Ghost of Tom Joad”: Resurrecting Steinbeck’s Gaze Candidate: Anna Bayo Ibars Supervisor: Dr David Owen Department: Filologia Anglesa i Germanística, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona September 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………………..1 PART ONE…………………………………………………………………………......5 1.1. Steinbeck: Context and Work………………………………………………..…...5 1.2. Springsteen: Context and Work………………………………………………….9 1.3. The vision of American life through the work of Steinbeck and Springsteen..14 PART TWO 2. Reading Bruce Springsteen’s lyrics: “Searching for the ghost of Tom Joad”...23 2.1. Searching for the ghost of Tom Joad …………………………………………23 2.1.1. Still searching for the ghost…………………………………………………...26 2.2. Waitin’ on the ghost of Tom Joad……………………………………………..30 2.2.1. Still waitin’ on the ghost……………………………………………………...35 2.3. With the ghost of old Tom Joad……………………………………………….38 CONCLUSION………………………………………………………………………44 WORKS CITED……………………………………………………………………..46 APPENDIX…………………………………………………………………………..49 1 “Searching for the Ghost of Tom Joad”: Resurrecting Steinbeck’s Gaze INTRODUCTION What is this land America? So many travel there, I‘m going now while I‘m still young my darling meet me there Wish me luck my lovely I‘ll send for you when I can And we‘ll make our home in the American Land. 1 The words “American Land”, made famous by the US singer-songwriter Pete Seeger and translated from a 1940’s song by Andrew Kovaly, a Slovakian immigrant, would appear to point to a sense of hope and plenty, referring to a place where the poem’s protagonist could fulfill his desire of a decent job and a home in the promised land. -

{FREE} All Summer Long Kindle

ALL SUMMER LONG PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Susan Mallery | 376 pages | 31 Jul 2012 | Harlequin (UK) | 9780373776948 | English | Richmond, United Kingdom All Summer Long PDF Book Problems playing this file? Some of us had champagne on set and it shows. Metacritic Reviews. International Federation of the Phonographic Industry Denmark. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Written by Huggo. US Mainstream Top 40 Billboard [36]. July Nestled amongst the northern Arizona pine trees is three days of art, music, and kid-friendly activities. February Trailers and Videos. The idea for the mashup was suggested by Mike E. Note Hallmark people We'll Run Away [Stereo] G. Netherlands Dutch Top 40 [43]. Sweden Sverigetopplistan [26]. Features Interviews Lists. It's never the wrong time to perfect your skin care routine. See also: Summer's Best Dresses. Okay, Hallmarkies, who will be watching AllSummerLong, costarring the delightful brennanelliott2 — and this sweet vintage yacht— this weekend??? This section does not cite any sources. Nashel Leto was forced to focus on the walls closing in and couldn't afford to think about helping young hopefuls get a foot in the door. October Streaming Picks. Attend the Mendota Sweet Corn Festival. Wilson, Love, Al Jardine. The best pre Beach Boys album featured their brilliant number one single "I Get Around," as well as other standout cuts in the beautifully sad "Wendy," "Little Honda" one of their best hot rod tunes, covered by the Hondells for a hit , and their remake of the late-'50s doo wop classic "Hushabye. Which artists are in the running for song of the summer? Films viewed. -

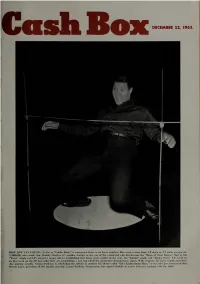

“Limbo Rock” Is Concerned, There Is No Lower Number

HOW LOW CAN YOU GO; As far as “Limbo Rock” is concerned, there is no lower number. This week it went from #2 down to #1 while passing the 1,300,000 sales mark. For Chubby Checker it’s another feather in the cap of the young lad who has become the “Dean of Teen Dance.” Just as his “Twist” single and LP’s played a major role in establishing that dance craze earlier in the year, his “Limho” single and “Limbo Party” LP (#35 in its first week on the LP best seller list) are establishing a new fad which the performer demonstrates above. With requests for more Limbo merchan- dise gaining steadily, Cameo/Parkway is scheduling the release of another CC album called “Let’s Limbo Some More.” It was also just announced that Bernie Lowe, president of the rapidly growing Cameo/Parkway Corporation, has signed Chubby to a new five-year contract with the label. HOT AJfllMt^Christmas STEVE LAWRENCE Fthe ballad of 1 SEEIN’ISBELIEVIN JED CLAMPETT EDDIE CARL BUTLER HODGES FLATT AND SCRUGGS L 4-42606 A Also available on single : Ccish Bm Cash Box Vol. XXIV—Number 15 December 22, 1962 FOUNDED BY BILL GERSH Gash Box (Publication Office) 1780 Broadway New York 19, N. Y. (Phone: JUdson 6-2640) CABLE ADDRESS: CASHBOX, N. Y. THE RECORD INDUSTRY JOE ORLECK, President and Publisher NORMAN ORLECK, VP and Managing Director GEORGE ALBERT, VP and Treasurer EDITORIAL—Music MARTY OSTROW, Editor-in-Chief IRA HOWARD, Editor IRV LICHTMAN, Associate Editor 1962 DICK ZIMMERMAN, Editorial Assistant MIKE MARTUCCI, Editorial Assistant BOB ETTINGER, Editorial Assistant POPSIE, Staff Photographer ADVERTISING BOB AUSTIN, National Director, Music JERRY SHIFRIN, N.Y.C. -

Mayor's Task Force on Heritage, Culture and Arts

2017 Mayor’s Task Force on Heritage, Culture and Arts Prepared by: Photo Credits Cover page: Jazz Winnipeg free concert in Old Market Square. Photo: Travis Ross. Provided by the Winnipeg Arts Council. Page 1: Mass Appeal 2016. Choice performance at Union Station. Photo: Matt Duboff. Provided by the Winnipeg Arts Council. Page 4 (Figure 1): Le Musée de Saint-Boniface Museum. Photo provided by Travel Manitoba. Dalnavert Museums. Photo provided by Heritage Winnipeg. Page 7: Red River College in the Exchange District. Photo provided by Heritage Winnipeg. Page 13: Pantages Playhouse Theatre. Photo: Andrew McLaren. Page 16: Public art tour visits Untitled by Cliff Eyland. Photo: Lindsey Bond. Provided by the Winnipeg Arts Council. Page 19: Cloud, Nuit Blanche installation by Caitlind r.c. Brown and Wayne Garrett. Photo: Cole Moszynski. Provided by the Winnipeg Arts Council. Message from the Chair Dear Mayor Bowman: I am pleased to present to you the report of the Task Force on Heritage, Culture and Arts, including recommendations and accompanying action items. The assignment was both challenging and exciting, and I would like to thank you for creating an opportunity for heritage (including museums), arts, culture and tourism sub-sectors to come together to start a conversation, develop a dialogue of collaboration, and provide recommendations towards enhancing Winnipeg’s cultural identity. I can tell you that Task Force members were very pleased to have been able to come together noting it was the first time their sub-sectors came together to act in an advisory capacity to the Mayor of Winnipeg! One of our key challenges was to explore new and innovative opportunities to broaden the revenue base for arts, culture and heritage and to explore alternative sources of dedicated capital funding.