Pech—Women and the Violin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Desert Island Times 18

D E S E RT I S L A N D T I M E S S h a r i n g f e l l o w s h i p i n NEWPORT SE WALES U3A No.18 17th July 2020 Commercial Street, c1965 A miscellany of Contributions from OUR members 1 U3A Bake Off by Mike Brown Having more time on my hands recently I thought, as well as baking bread, I would add cake-making to my C.V. Here is a Bara Brith type recipe that is so simple to make and it's so much my type of cake that I don't think I'll bother buying one again. (And the quantities to use are in 'old money'!!) "CUP OF TEA CAKE" Ingredients 8oz mixed fruit Half a pint of cooled strong tea Handful of dried mixed peel 8oz self-raising flour # 4oz granulated sugar 1 small egg # Tesco only had wholemeal SR flour (not to be confused � with self-isolating flour - spell checker problem there! which of course means "No Flour At All!”) but the wholemeal only enhanced the taste and made it quite rustic. In a large bowl mix together the mixed fruit, mixed peel and sugar. Pour over the tea, cover and leave overnight to soak in the fridge. Next day preheat oven to 160°C/145°C fan/Gas Mark 4. Stir the mixture thoroughly before adding the flour a bit at a time, then mix in the beaten egg and stir well. Grease a 2lb/7" loaf tin and pour in the mixture. -

Georges Enesco Au Conservatoire De Paris (1895 – 1899)

GEORGES ENESCO AU CONSERVATOIRE DE PARIS (1895 – 1899) JULIEN SZULMAN VIOLON PIERRE-YVES HODIQUE PIANO GEORGES ENESCO AU CONSERVATOIRE DE PARIS (1895 – 1899) GEORGES ENESCO ANDRÉ GÉDALGE GEORGES ENESCO MARTIN-PIERRE MARSICK Sonate n°1 pour piano et violon Sonate n°1 pour piano et violon Sonate n°2 pour piano et violon 11. Attente - Poème d’été opus 2 opus 12 opus 6 pour violon et piano 1. Allegro vivo — 7’42 4. Allegro moderato 8. Assez mouvementé — 8’40 opus 24 n°3 — 3’56 — 2’18 2. Quasi adagio — 9’28 e tranquillamente 9. Tranquillement — 7’12 3. Allegro — 8’00 5. Vivace — 3’35 10. Vif — 7’49 6. Adagio non troppo — 3’34 7. Presto con brio — 3’34 durée totale — 75’51 JULIEN SZULMAN — VIOLON PIERRE-YVES HODIQUE — PIANO RETOUR AUX SOURCES Élève d’un élève du violoniste Christian Halphen, dédiée à Enesco, composée final est indiqué « trompette », représentant Nationale de France. À de rares exceptions Ferras, j’ai très tôt été fasciné par la figure de seulement à partir de juillet 1899, et donc « un gosse de Poulbot ». L’écoute des près, les nombreux doigtés indiqués par son mentor Georges Enesco. Compositeur, postérieure aux études du violoniste au deux enregistrements du compositeur Marsick ont été respectés. violoniste, pianiste, chef d’orchestre : Conservatoire. Ce programme permet de (avec Chailley-Richez, et en 1943 avec la multiplicité de ses talents en fait une découvrir la personnalité marquante du Dinu Lipatti) est riche d’enseignements sur Ces différentes sources me sont d’une figure incontournable de l’histoire de la jeune Georges Enesco, et l’environnement la liberté du jeu des musiciens et du choix aide précieuse pour m’approcher au plus musique de la première moitié du XXe siècle. -

Booklet 125X125.Indd

1 2 3 CONTENTS A RECORDED HISTORY Philip Stuart 7 REMINISCENCES BY LADY MARRINER 18 A FEW WORDS FROM PLAYERS 21 HISTORY OF THE ACADEMY OF SAINT MARTIN IN THE FIELDS Susie Harries (née Marriner) 36 CD INFORMATION 44 INDEX 154 This Edition P 2020 Decca Music Group Limited Curation: Philip Stuart Project Management: Raymond McGill & Edward Weston Digital mastering: Ben Wiseman (Broadlake Studios) TH 60 ANNIVERSARY EDITION Design & Artwork by Paul Chessell Special thanks to Lady Marriner, Joshua Bell, Marilyn Taylor, Andrew McGee, Graham Sheen, Kenneth Sillito, Naomi Le Fleming, Tristan Fry, Robert Smissen, Lynda Houghton, Tim Brown, Philip Stuart, Susie Harries, Alan Watt, Ellie Dragonetti, Gary Pietronave (EMI Archive, Hayes) 4 5 A RECORDED HISTORY Philip Stuart It all started with L’Oiseau-Lyre - a boutique record label run by a Paris-based Australian heiress who paid the players in cash at the end of the session. The debut LP of Italianate concerti grossi had a monochrome photograph of a church porch on the cover and the modest title “A Recital”. Humble beginnings indeed, but in 1962 “The Gramophone” devoted a full page to an enthusiastic review, concluding that it was played “with more sense of style than all the chamber orchestras in Europe put together”. Even so, it was more than a year before the sequel, “A Second Recital”, appeared. Two more such concert programmes ensued [all four are on CDs 1-2] but by then the Academy had been taken up by another label with a shift in policy more attuned to record collectors than to concert goers. -

Norwegian Chamber Orchestra IONA BROWN, Artistic Director

THE UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN Norwegian Chamber Orchestra IONA BROWN, Artistic Director IONA BROWN and ATLE SPONBERG, Violinists LARS ANDERS TOMTER, Violist THURSDAY EVENING, OCTOBER 8, 1987, AT 8:00 RACKHAM AUDITORIUM, ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN PROGRAM Concerto in D minor for Two Violins .............................. BACH Vivace Largo, ma non tanto Allegro IONA BROWN and ATLE SPONBERG, Violinists Rendez-vous for Strings (1987), American premiere........ ARNE NORDHEIM Praembulum Intermezzo Eco INTERMISSION String Symphony No. 10 .................................. MENDELSSOHN In one movement Sinfonia Concertante in E-flat major, K. 364, for Violin and Viola .......................................... MOZART Allegro maestoso Andante Presto IONA BROWN, Violinist, and LARS ANDERS TOMTER, Violist The Norwegian Chamber Orchestra acknowledges with gratitude the following companies who have helped to make possible its 1987 North American tour: Norseland Foods, Norsk Hydro Sales Corporation (New York), and Olsten Services. Hall's Cough Tablets, courtesy of Warner-Lambert Company, are available in the lobby. Fifth Concert of the 109th Season Twenty-fifth Annual Chamber Arts Series Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750): Concerto in D minor for Two Violins This concerto is very likely the best known of all Baroque concertos for two instruments. Stravinsky once called it "the most perfect Baroque concerto in existence." Written while Bach was Kapellmeister at the small but musically active court in Kothen, from 1717 to 1723, it follows the pattern of the Italian concerto with its two fast movements and an aria-like slow movement in the middle. Arne Nordheim (b. 1931): Rendez-vous for Strings (1987) Rendez-vous for Strings is a brand new composition, written specially for the Norwegian Chamber Orchestra. -

L.A. Chamber Orchestra's 2018-19 Season Features Three World Premieres

L.A. Chamber Orchestra's 2018-19 Season Features Three World Premieres broadwayworld.com/los-angeles/article/LA-Chamber-Orchestras-2018-19-Season-Features-Three-World-Premieres- 20180129 by BWW News January 29, 2018 Desk Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra (LACO), one of the nation's premier music ensembles and a leader in presenting wide-ranging repertoire and adventurous commissions, announces broadened collaborations and inventive new programming for its 2018-19 season. Opening in September 2018 and continuing into May 2019, the season spotlights LACO's virtuosic artists and builds upon the Orchestra's five decades of intimate and transformative musical programs. Highlighting an eight-program Orchestral Series are two world premieres and a West Coast premiere, all LACO commissions/co-commissions, including the world premiere of celebrated film composer James Newton Howard's Cello Concerto, a world premiere by Los Angeles composer Sarah Gibson and a West Coast premiere by Bryce Dessner, best known as a member of the Grammy Award-nominated band The National and a force in new music. The series also features a broad array of works by other internationally- renowned living composers, among them LACO's Creative Advisor Andrew Norman, Matthias Pintscher, Arvo Pärt and Gabriella Smith. A versatile and diverse array of exceptional guest artists range from classical music's most eminent to those who have more recently established themselves as among the most compelling musicians of their generation. They include Hilary Hahn and Jennifer Koh, violins; Jonathan Biss, piano; Anthony McGill, clarinet; Lydia Teuscher, soprano; Kelley O'Connor and Michelle DeYoung, mezzo-sopranos; Tuomas Katajala, tenor; and conductors David Danzmayr, Thomas Dausgaard, Bernard Labadie, Jaime Martín, Gemma New, Peter Oundjian, Pintscher and Jeffrey Kahane, who stepped down as LACO Music Director in June 2017 after a 20-year tenure and makes his second appearance as Conductor Laureate. -

Ambassador Auditorium Collection ARS.0043

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt3q2nf194 No online items Guide to the Ambassador Auditorium Collection ARS.0043 Finding aid prepared by Frank Ferko and Anna Hunt Graves This collection has been processed under the auspices of the Council on Library and Information Resources with generous financial support from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Archive of Recorded Sound Braun Music Center 541 Lasuen Mall Stanford University Stanford, California, 94305-3076 650-723-9312 [email protected] 2011 Guide to the Ambassador Auditorium ARS.0043 1 Collection ARS.0043 Title: Ambassador Auditorium Collection Identifier/Call Number: ARS.0043 Repository: Archive of Recorded Sound, Stanford University Libraries Stanford, California 94305-3076 Physical Description: 636containers of various sizes with multiple types of print materials, photographic materials, audio and video materials, realia, posters and original art work (682.05 linear feet). Date (inclusive): 1974-1995 Abstract: The Ambassador Auditorium Collection contains the files of the various organizational departments of the Ambassador Auditorium as well as audio and video recordings. The materials cover the entire time period of April 1974 through May 1995 when the Ambassador Auditorium was fully operational as an internationally recognized concert venue. The materials in this collection cover all aspects of concert production and presentation, including documentation of the concert artists and repertoire as well as many business documents, advertising, promotion and marketing files, correspondence, inter-office memos and negotiations with booking agents. The materials are widely varied and include concert program booklets, audio and video recordings, concert season planning materials, artist publicity materials, individual event files, posters, photographs, scrapbooks and original artwork used for publicity. -

Memorials of Old Dorset

:<X> CM \CO = (7> ICO = C0 = 00 [>• CO " I Hfek^M, Memorials of the Counties of England General Editor : Rev. P. H. Ditchfield, M.A., F.S.A. Memorials of Old Dorset ?45H xr» MEMORIALS OF OLD DORSET EDITED BY THOMAS PERKINS, M.A. Late Rector of Turnworth, Dorset Author of " Wimborne Minster and Christchurch Priory" ' " Bath and Malmesbury Abbeys" Romsey Abbey" b*c. AND HERBERT PENTIN, M.A. Vicar of Milton Abbey, Dorset Vice-President, Hon. Secretary, and Editor of the Dorset Natural History and Antiquarian Field Club With many Illustrations LONDON BEMROSE & SONS LIMITED, 4 SNOW HILL, E.C. AND DERBY 1907 [All Rights Reserved] TO THE RIGHT HONOURABLE LORD EUSTACE CECIL, F.R.G.S. PAST PRESIDENT OF THE DORSET NATURAL HISTORY AND ANTIQUARIAN FIELD CLUB THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED BY HIS LORDSHIP'S KIND PERMISSION PREFACE editing of this Dorset volume was originally- THEundertaken by the Rev. Thomas Perkins, the scholarly Rector of Turnworth. But he, having formulated its plan and written four papers therefor, besides gathering material for most of the other chapters, was laid aside by a very painful illness, which culminated in his unexpected death. This is a great loss to his many friends, to the present volume, and to the county of for Mr. Perkins knew the as Dorset as a whole ; county few men know it, his literary ability was of no mean order, and his kindness to all with whom he was brought in contact was proverbial. After the death of Mr. Perkins, the editing of the work was entrusted to the Rev. -

Musical Performance and Cocktail Reception September 08, 2011

Musical Performance and Cocktail Reception September 08, 2011 The Consul General of the Czech Republic in Los Angeles, Michal Sedlacek, will host the Garden Party in his residence in honor of the 170th anniversary of the birth of classical composer Antonin Dvořák. The Salastina Music Society and Walden String Quartet will present a few samples of Dvořák’s work. Music Professors Robert Winter of UCLA and Nick Strimple of USC will speak briefly on the importance of Dvořák in American music. Film Producer/Actor Lenora May and Emmy Award winner Craig Heller will take you inside the fascinating world of independent filmmaking for a detailed look at their upcoming film project, Spillville, the true story of Dvořák's inspirational 1893 trip to Spillville, Iowa (participation upon invitation only). Deo Gratias (directed by Martin Suchanek), September 14 and 21 at 7:30 pm Film documentary depicting Dvorak´s life and work (English subtitles) Screening at the Consulate General of the Czech Republic 10990 Wilshire Blvd, Ste 1100, Los Angeles CA 90024 A documentary that portrays the world-renowned Czech composer as a man of strong character, sensitivity, education and Christian faith, as a patriot and a man whose talent took him from a very modest family background to the highest peak of fame. How was it that a musician unknown until the age of 33 became adored all over Europe, was invited to the USA to help create a national American music, and was awarded doctorates and honorary memberships from top international orchestras? From where did Dvořák draw the strength to preserve his own unique identity and not succumb to contemporary fashion trends? All these questions are addressed in this fascinating documentary. -

Program Notes Pima Community College Recital Hall April 17, 2014 7:00 PM Mark Nelson, Tuba Marie Sierra, Piano

Mark Nelson Tuba Recital Program Notes Pima Community College Recital Hall April 17, 2014 7:00 PM Mark Nelson, tuba Marie Sierra, piano Performers Marie Sierra is a professional pianist who performs collaboratively in over 40 concerts annually and is formerly the staff pianist for the Tucson Girls Chorus and currently the staff pianist for the Tucson Boys Chorus. Recently, Marie has performed and recorded with Artists Michael Becker (trombone) and Viviana Cumplido (Flute). She has also recorded extensively with Yamaha Artist and Saxophonist, Michael Hester, on Seasons and An American Patchwork. Marie is in demand as an accompanist throughout the United States and Mexico. Additionally, she has performed at numerous international music conferences, including the 2010 International Tuba Euphonium Conference in Tucson. Marie has served on the faculties of the Belmont University in Nashville, and the Blair School of Music at Vanderbilt University. Ms. Sierra earned her Bachelor’s degree and Master’s degree in Piano Performance at the University of Miami. Program Six Romances Without Words, op. 76 by Cécile Chaminade (1857-1944) arranged by Ralph Sauer Published by Cherry Classics Music. www.Cherry-Classics.com. The Six Romances Without Words was originally a piano work written in 1893-1894. Like many works of the time, it would typically be played for small audiences in a parlor or small hall. The melodies are all fitting for the tuba and the harmonies are interesting but not too modern. The arranger, Ralph Sauer, has placed the movements in a different order than the original work to facilitate more of a grand finale than a reflective last movement. -

Sacred Song Sisters: Choral and Solo Vocal Church Music by Women Composers for the Lenten Revised Common Lectionary

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones 5-1-2020 Sacred Song Sisters: Choral and Solo Vocal Church Music by Women Composers for the Lenten Revised Common Lectionary Lisa Elliott Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Composition Commons, and the Other Music Commons Repository Citation Elliott, Lisa, "Sacred Song Sisters: Choral and Solo Vocal Church Music by Women Composers for the Lenten Revised Common Lectionary" (2020). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 3889. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/19412066 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SACRED SONG SISTERS: CHORAL AND SOLO VOCAL CHURCH MUSIC BY WOMEN COMPOSERS FOR THE LENTEN REVISED COMMON LECTIONARY By Lisa A. Elliott Bachelor of Arts-Music Scripps College 1990 Master of Music-Vocal Performance San Diego State University 1994 A doctoral project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Musical Arts School of Music College of Fine Arts Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas May 2020 Copyright 2020 Lisa A. -

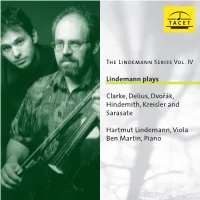

Lindemann Plays Clarke, Delius, Dvorák, Hindemith

CYAN MAGENTA GELB SCHWARZ Booklet T 095 Seite 32 CYAN MAGENTA GELB SCHWARZ Booklet T 095 Seite 1 COVER Rebecca Clarke (1886 – 1979) Sonata for viola and piano (1919) 23'18 1 Impetuoso 7'51 2 Vivace 4'02 3 Adagio – Allegro 11'25 Paul Hindemith (1895 – 1963) Sonate für Viola und Klavier op.11, Nr. 4 17'42 4 Fantasie. Ruhig 3'21 The Lindemann Series Vol. IV 5 Thema mit Variationen. Ruhig und einfach 4'39 6 Finale (mit Variationen). Sehr lebhaft 9'42 Lindemann plays Fritz Kreisler (1875 – 1962) 7 Sicilienne et Rigaudon im Stile von Francoeur 4'43 Clarke, Delius, Dvorák,ˇ Hindemith, Kreisler and Antonin Dvorákˇ (1841 – 1904) / Fritz Kreisler Sarasate Slawischer Tanz Nr. 2 8 Andante grazioso quasi Allegretto 5'04 Hartmut Lindemann, Viola Pablo de Sarasate (1844 – 1908) Ben Martin, Piano Zigeunerweisen 9 Moderato – Allegro molto vivace 8'58 Frederick Delius (1862 – 1934) / Arr.: Lionel Tertis Serenade aus »Hassan« 5 bl 3'27 9 Con moto moderato T E C A Hartmut Lindemann, Viola · Ben Martin, Piano T CYAN MAGENTA GELB SCHWARZ TS Tonträger CYAN MAGENTA GELB SCHWARZ TS Tonträger A Nice Old-fashioned Programme granted the blessing of loving a woman as nata to Berkshire and Pittsfield. In the first much as he loved her. Clarke and Friskin, now round ten compositions were chosen out of a Foreword Stanford (who also advised her to switch to the both 58 years old, married on Saturday the total of 73 which had been sent in. In the sec- He wanted to put together a “nice old-fash- viola) and counterpoint under Sir Frank Bridge; 23 rd September 1944 in New York. -

Branding Brussels Musically: Cosmopolitanism and Nationalism in the Interwar Years

BRANDING BRUSSELS MUSICALLY: COSMOPOLITANISM AND NATIONALISM IN THE INTERWAR YEARS Catherine A. Hughes A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music. Chapel Hill 2015 Approved by: Annegret Fauser Mark Evan Bonds Valérie Dufour John L. Nádas Chérie Rivers Ndaliko © 2015 Catherine A. Hughes ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Catherine A. Hughes: Branding Brussels Musically: Cosmopolitanism and Nationalism in the Interwar Years (Under the direction of Annegret Fauser) In Belgium, constructions of musical life in Brussels between the World Wars varied widely: some viewed the city as a major musical center, and others framed the city as a peripheral space to its larger neighbors. Both views, however, based the city’s identity on an intense interest in new foreign music, with works by Belgian composers taking a secondary importance. This modern and cosmopolitan concept of cultural achievement offered an alternative to the more traditional model of national identity as being built solely on creations by native artists sharing local traditions. Such a model eluded a country with competing ethnic groups: the Francophone Walloons in the south and the Flemish in the north. Openness to a wide variety of music became a hallmark of the capital’s cultural identity. As a result, the forces of Belgian cultural identity, patriotism, internationalism, interest in foreign culture, and conflicting views of modern music complicated the construction of Belgian cultural identity through music. By focusing on the work of the four central people in the network of organizers, patrons, and performers that sustained the art music culture in the Belgian capital, this dissertation challenges assumptions about construction of musical culture.