Nantucket Nectars

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Keurig to Acquire Dr Pepper Snapple for $18.7Bn in Cash

Find our latest analyses and trade ideas on bsic.it Coffee and Soda: Keurig to acquire Dr Pepper Snapple for $18.7bn in cash Dr Pepper Snapple Group (NYSE:DPS) – market cap as of 17/02/2018: $28.78bn Introduction On January 29, 2018, Keurig Green Mountain, the coffee group owned by JAB Holding, announced the acquisition of soda maker Dr Pepper Snapple Group. Under the terms of the reverse takeover, Keurig will pay $103.75 per share in a special cash dividend to Dr Pepper shareholders, who will also retain 13 percent of the combined company. The deal will pay $18.7bn in cash to shareholders in total and create a massive beverage distribution network in the U.S. About Dr Pepper Snapple Group Incorporated in 2007 and headquartered in Plano (Texas), Dr Pepper Snapple Group, Inc. manufactures and distributes non-alcoholic beverages in the United States, Mexico and the Caribbean, and Canada. The company operates through three segments: Beverage Concentrates, Packaged Beverages, and Latin America Beverages. It offers flavored carbonated soft drinks (CSDs) and non-carbonated beverages (NCBs), including ready-to-drink teas, juices, juice drinks, mineral and coconut water, and mixers, as well as manufactures and sells Mott's apple sauces. The company sells its flavored CSD products primarily under the Dr Pepper, Canada Dry, Peñafiel, Squirt, 7UP, Crush, A&W, Sunkist soda, Schweppes, RC Cola, Big Red, Vernors, Venom, IBC, Diet Rite, and Sun Drop; and NCB products primarily under the Snapple, Hawaiian Punch, Mott's, FIJI, Clamato, Bai, Yoo- Hoo, Deja Blue, ReaLemon, AriZona tea, Vita Coco, BODYARMOR, Mr & Mrs T mixers, Nantucket Nectars, Garden Cocktail, Mistic, and Rose's brand names. -

DR PEPPER SNAPPLE GROUP ANNUAL REPORT DPS at a Glance

DR PEPPER SNAPPLE GROUP ANNUAL REPORT DPS at a Glance NORTH AMERICA’S LEADING FLAVORED BEVERAGE COMPANY More than 50 brands of juices, teas and carbonated soft drinks with a heritage of more than 200 years NINE OF OUR 12 LEADING BRANDS ARE NO. 1 IN THEIR FLAVOR CATEGORIES Named Company of the Year in 2010 by Beverage World magazine CEO LARRY D. YOUNG NAMED 2010 BEVERAGE EXECUTIVE OF THE YEAR BY BEVERAGE INDUSTRY MAGAZINE OUR VISION: Be the Best Beverage Business in the Americas STOCK PRICE PERFORMANCE PRIMARY SOURCES & USES OF CASH VS. S&P 500 TWO-YEAR CUMULATIVE TOTAL ’09–’10 JAN ’10 MAR JUN SEP DEC ’10 $3.4B $3.3B 40% DPS Pepsi/Coke 30% Share Repurchases S&P Licensing Agreements 20% Dividends Net Repayment 10% of Credit Facility Operations & Notes 0% Capital Spending -10% SOURCES USES 2010 FINANCIAL SNAPSHOT (MILLIONS, EXCEPT EARNINGS PER SHARE) CONTENTS 2010 $5,636 NET SALES +2% 2009 $5,531 $ 1, 3 21 SEGMENT +1% Letter to Stockholders 1 OPERATING PROFIT $ 1, 310 Build Our Brands 4 $2.40 DILUTED EARNINGS +22% PER SHARE* $1.97 Grow Per Caps 7 Rapid Continuous Improvement 10 *2010 diluted earnings per share (EPS) excludes a loss on early extinguishment of debt and certain tax-related items, which totaled Innovation Spotlight 23 cents per share. 2009 diluted EPS excludes a net gain on certain 12 distribution agreement changes and tax-related items, which totaled 20 cents per share. See page 13 for a detailed reconciliation of the Stockholder Information 12 7 excluded items and the rationale for the exclusion. -

All Products Are Pareve Unless Indicated D=Dairy Or M=Meat

New to All products are pareve unless indicated D=Dairy or M=Meat. Due to limited space, this list contains only products manufactured by companies and/or plants certified within the last three months. Brands listed directly beneath one another indicate that the product list immediately below is identical for all brands. PR ODUCTS ARE CERTIF I E D ONLY WH EN BEARING TH E SYMBOL Compiled by Zeh a va Ful d a 4c Seltzer Citrus Mist Green Tea Cappuccino French Vanilla Iced Tonic Water Golden Cola Champagne Green Tea W/ginseng & Plum Juice Tea Mix ........................................D Tropical Punch Wild Cherry Seltzer Green Tea W/honey & Ginseng Cappuccino Mix-coffee Flavor..........D Vanilla Cream Soda Green Tea With Ginseng & Asia Plum Cappuccino Mix-mocha Flavor........D Wildberry Seltzer American Dry Green Tea With Ginseng And Honey Iced Tea Mix-decaffeinated Yellow Lightning Club Soda Green Tea With Honey (64oz) Iced Tea Mix-lemon Flavor Green Tea With Honey And Ginseng Anderson Erickson Iced Tea Mix-peach Flavor Adirondack Clear ‘n’ Natural Honey Lemon Premium Tea Blue Raspberry Fruit Bowl................D Iced Tea Mix-raspberry Flavor Blackberry Soda Kahlua Iced Coffee ..........................D Lite Egg Nog....................................D Iced Tea Mix-sugar Free Cherry Soda Latte Supreme..................................D Lemonade Flavor Drink Mix Cranberry Soda Lemon Iced Tea Diet Cranberry Soda Anytime Drink Crystals Lemon Tea A & W Diet Loganberry Soda Lemonade W/10% Real Lemon Juice Cream Soda Diet Raspberry Lime Soda -

Keurig Dr Pepper Annual Report 2021

Keurig Dr Pepper Annual Report 2021 Form 10-K (NYSE:KDP) Published: February 25th, 2021 PDF generated by stocklight.com UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K ☒ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDED December 31, 2020 OR ☐ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 FOR THE TRANSITION PERIOD FROM TO COMMISSION FILE NUMBER 001-33829 kdp-20201231_g1.jpg Keurig Dr Pepper Inc. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 98-0517725 (State or other jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) (I.R.S. employer identification number) 53 South Avenue Burlington, Massachusetts 01803 (Address of principal executive offices) (781) 418-7000 (Registrant's telephone number, including area code) Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes ☒ No ☐ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Exchange Act. Yes ☐ No ☒ Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. Yes ☒ No ☐ Indicate by check mark whether the registrant has submitted electronically every Interactive Data File required to be submitted pursuant to Rule 405 of Regulation S-T (§232.405 of this chapter) during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to submit such files). -

Dr Pepper Snapple Group, Inc Annual Report 2018

Dr Pepper Snapple Group, Inc Annual Report 2018 Form 10-K (NYSE:DPS) Published: February 14th, 2018 PDF generated by stocklight.com UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D. C. 20549 Form 10-K x ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2017 or o TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to C ommission file number 001-33829 (Exact name of Registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 98-0517725 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. employer incorporation or organization) identification number) 5301 Legacy Drive, Plano, Texas 75024 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip code) Registrant's telephone number, including area code: (972) 673-7000 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of Each Class Name of Each Exchange on Which Registered COMMON STOCK, $0.01 PAR VALUE NEW YORK STOCK EXCHANGE Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yesx No o Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Exchange Act. Yes o No x Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

Keurig Dr Pepper Annual Report 2021

Keurig Dr Pepper Annual Report 2021 Form 10-K (NASDAQ:KDP) Published: February 25th, 2021 PDF generated by stocklight.com UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K ☒ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDED December 31, 2020 OR ☐ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 FOR THE TRANSITION PERIOD FROM TO COMMISSION FILE NUMBER 001-33829 kdp-20201231_g1.jpg Keurig Dr Pepper Inc. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 98-0517725 (State or other jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) (I.R.S. employer identification number) 53 South Avenue Burlington, Massachusetts 01803 (Address of principal executive offices) (781) 418-7000 (Registrant's telephone number, including area code) Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes ☒ No ☐ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Exchange Act. Yes ☐ No ☒ Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. Yes ☒ No ☐ Indicate by check mark whether the registrant has submitted electronically every Interactive Data File required to be submitted pursuant to Rule 405 of Regulation S-T (§232.405 of this chapter) during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to submit such files). -

Spring 06 Web Final.Pdf

www.BeverageWarehouse.com BBeevveerraaggee PPuurrvveeyyoorrss SSiinnccee 11997700 •WATER •JUICES •SOFT DRINKS •SNACKS •FINE WINE •CHAMPAGNE •VODKA •GIN •RUM •TEQUILA •BOURBON •PORT •COGNAC •LIQUEURS S p r i n g 2 0 0 6 •MIXERS •BEER •BLENDED & SINGLE MALT SCOTCHES •NON-AALCOHOLIC BEER •& MUCH MORE Open to the public MON-SAT 9am-6pm & SUN 10am-4pm WE ALSO DELIVER... Call us today.. 310-306-2822 WATER NATURAL ARTESIAN CRYSTAL GEYSER Sparkling MINERAL Water: SPRING WATER 00482 Plain 450 year old rain water passes through nature’s 00812 Lemon elaborate filtration system, giving 00811 Orange FIJI Natural Artesian Water unparalleled purity 00810 Lime Case of 24 / 18oz Plastic Btl . .$12.99 that provides consumers with the best possible 00789 Plain 24 / 12oz Glass Btl . .$12.99 taste in water …enjoy! CRYSTAL GEYSER Sparkling Water With Juice: 00665 24 / 16oz Plastic Btl . .$23.96 00234 Cranberry / Black Cherry 12877 12 / 1Ltr Plastic Btl . .$21.99 00792 Passion Mango 14120 12 / 1.5Ltr Plastic Btl . .$23.99 00793 Pink Lemonade 00794 Raspberry 00795 Ruby Red Grapefruit 00796 Wild Berry PENTA Case of 24 / 12oz Glass Btls . .$18.99 CALISTOGA Sparkling MINERAL Water: PURIFIED DRINKING WATER 00757 Black Cherry This “redefined” purified drinking water is made mostly of small 00763 Lime water clusters, better for hydration, so the body doesn’t have to break 00769 Plain down as many of the clusters to hydrate cells. It is also oxygenated to further enhance its hydration capabilities, plus contains no artificial 00759 Lemon Case of 24 / 10oz Glass Btls . .$11.96 ingredients, no chemicals, no minerals and no calories. -

Download 2018 Annual Report

2018 ANNUAL REPORT KEURIG DR PEPPER PEPPER DR KEURIG • 2018 ANNUAL REPORT ANNUAL 2018 THE POWER OF HOT AND COLD 53 South Avenue, Burlington, MA 01803 • 5301 Legacy Drive, Plano, TX 75024 keurigdrpepper.com FINANCIAL RESULTS All information is presented on an Adjusted pro forma basis* CORPORATE & INVESTOR INFORMATION Twelve months ended December 31 in millions, except earnings per share 2018 2017 Change CORPORATE HEADQUARTERS VIRTUAL ANNUAL MEETING OF Net Sales $11,024 $10,775 +2.3% 53 South Avenue STOCKHOLDERS Cost of Sales 4,870 4,841 +0.6% Burlington, MA 01803 The annual meeting of stockholders will take Selling, General and Administrative Expenses 3,550 3,533 +0.5% 877.208.9991 place online on June 7, 2019, at 11 a.m., EDT. The Other Operating (Income) Expense, Net (16) (55) -70.9% meeting will be conducted via live webcast at Income from Operations 2,620 2,456 +6.7% 5301 Legacy Drive www.virtualshareholdermeeting.com/KDP2019. % Net Sales 23.8% 22.8% +100 bps Plano, TX 75024 Interest Expense 657 680 -3.4% 800.527.7096 TRANSFER AGENT Other (Income) Expense, Net (11) 81 NM Computershare Trust Company, N.A. Income before Taxes 1,974 1,695 +16.5% STOCK EXCHANGE LISTING c/o Computershare, Inc. Provision for Income Taxes 523 513 +1.9% New York 250 Royall Street Effective Tax Rate 26.5% 30.3% -380 bps Ticker Symbol: KDP Canton, MA 02021 877.745.9312 Net Income 1,451 1,182 +22.8% INVESTOR RELATIONS Diluted Earnings Per Share $1.04 $0.85 +22.4% [email protected] INDEPENDENT REGISTERED PUBLIC 888.340.5287 ACCOUNTING FIRM Diluted Shares 1,401 1,387 +1.0% https://investors.keurigdrpepper.com/ Deloitte & Touche LLP 200 Berkeley St 10th Floor *Please refer to the Form 10-K, included with this report, for reconciliations from GAAP to Adjusted pro forma results. -

Evaluating Sugary Drink Nutrition and Marketing to Youth Methods

Evaluating Sugary Drink Nutrition and Marketing to Youth Methods Sugary Drink FACTS: Evaluating Sugary Drink Nutrition and Marketing to Youth Authors: Jennifer L. Harris, PhD, MBA Marlene B. Schwartz, PhD Kelly D. Brownell, PhD Johanna Javadizadeh, MBA Megan Weinberg, MA Vishnudas Sarda, MBBS, MPH Christina Munsell, MS, RD Carol Shin, MBA Fran Fleming Milici, PhD Amy Ustjanauskas Renee Gross Sarah Speers Andrew Cheyne, CPhil Lori Dorfman, DrPH Priscilla Gonzalez, MPH Pamela Mejia, MS, MPH Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity October, 2011 Acknowledgements We would like to thank the following people for their valuable assistance in collecting data: Susannah Albert-Chandhok Ryan Gebhard Darina Nghiem Josh Baker Eliza Gombert Eunie Park Kate Barnett Jay Imus Angel Reese Kelly Barrett Heather Kaplan Hannah Sheehy Casey Carden Carly Litzenberger Jennifer Shin Robert Dowding Benjamin Lovell Ashita Soni Ashley Firth, MA Lisa Martinez, MPH Kate Stearns We would also like to thank our steering committee and other advisors: Doug Blanke, JD Dale Kunkel, PhD Mary Story, PhD, RD Frank Chaloupka, PhD Tim Lobstein, PhD Stephen Teret, JD, MPH Thomas Farley, MD, MPH Susan T. Mayne, PhD Ellen Wartella, PhD Sonya A Grier, PhD, MBA C. Tracy Orleans, PhD James G. Webster, PhD Corinna Hawkes, PhD Lisa M. Powell, PhD Walter Willett, MD, DrPH Shiriki Kumanyika, PhD, MPH Amelie Ramirez, DrPH Jerome D. Williams, PhD Thank you to our colleagues at the Rudd Center, especially Andrea Wilson, Megan Orciari, and Tricia Wynne We thank Cavich Creative, LLC, and Chris Lenz for their assistance in preparing the manuscript and website. Finally, we thank the leadership and staff at the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, with special thanks to the Childhood Obesity Team. -

View These Patents As Valuable Assets but We Do Not View Any Single Patent As Critical to Our Success

KEURIG DR PEPPER DR KEURIG 2020 ANNUAL REPORT ANNUAL 2020 A MODERN BEVERAGE COMPANY 2020 ANNUAL REPORT FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS All Information is presented on an Adjusted basis* 2018–2020 All amounts are in millions except Earnings Per Share 2019–2020 2018 Two-Year Twelve months ended December 31 2020 2019 Change Pro Forma Avg. Change Net Sales $11,618 $11,120 4.5% $11,024 2.7% Constant Currency Net Sales Growth 5.0% 4.1% 1 Cost of Sales 5,092 4,792 6.3% 4,864 2.3% Selling, General and Administrative Expenses 3,374 3,483 -3.1% 3,556 -2.6% Other Operating (Income) Expense, Net (39) (45) NM (16) NM Income from Operations 3,191 2,890 10.4% 2,620 10.4% Constant Currency Income from Operations Growth 10.8% 10.7% % Net Sales 27.5% 26.0% 150 bps 23.8% 185 bps Interest Expense 542 553 -2.0% 635 -7.6% Other Income, Net 17 19 -10.5% 3 NM Income before Taxes 2,632 2,318 13.5% 1,982 15.2% Provision for Income Taxes 644 591 9.0% 524 10.9% Effective Tax Rate 24.5% 25.5% -100 bps 26.4% -100 bps Net Income 1,988 1,727 15.1% 1,458 16.8% Diluted Earnings Per Share $1.40 $1.22 14.8% $1.04 16.0% Diluted Shares 1,422 1,419 0.2% 1,401 0.7% * Please refer to the Form 10-K, included with this report, for reconciliations from GAAP to Adjusted results 1 Reflects underlying net sales growth 2018–2019 KDP Management Leverage Ratio* 2020 Net Sales by Segment in billions 12/31/20 3.6X 12/31/19 4.5X 2.4X 12/31/18 5.4X $0.5 7/9/18 6.0X $1.3 *See Management Leverage Ratio reconciliation and calculation on page 12 $4.4 Operating Cash Flow in billions 2020 $2.5 2019 $2.5 $5.4 2018 $1.6 Total Shareholder Return 150% 131% 2020 Net Sales 120% Constant Currency Growth 90% 84% Coffee Systems +4.8% 60% 54% Packaged Beverages +8.5% 30% 0% Beverage Concentrates -6.2% 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 Latin America Beverages +3.8% KDP1 S&P 500 S&P 500 Food & Beverage Index 1Represents DPS through 7/9/2018 and KDP 7/10/2018 to 12/31/2020 Bob Gamgort Chairman and Chief Executive Officer DEAR SHAREHOLDERS As I write this letter, cautious optimism is in the air. -

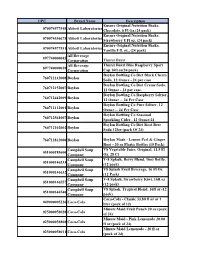

UPC Brand Name Description 070074577548

UPC Brand Name Description Ensure Original Nutrition Shake, 070074577548 Abbott Laboratories Chocolate, 8 Fl Oz (24 pack) Ensure Original Nutrition Shake, 070074536675 Abbott Laboratories Strawberry 8 Fl oz, (24 pack) Ensure Original Nutrition Shake, 070074577531 Abbott Laboratories Vanilla 8 fl. oz., (24 pack) All Beverage 897740000045 Corporation Thurst Burst All Beverage Thurst Burst Blue Raspberry Sport 897740000038 Corporation Cap 16fl oz(24 pack) Boylan Bottling Co Diet Black Cherry 760712142008 Boylan Soda, 12 Ounce - 24 per case Boylan Bottling Co Diet Creme Soda, 760712152007 Boylan 12 Ounce - 24 per case. Boylan Bottling Co Raspberry Seltzer, 760712442009 Boylan 12 Ounce -- 24 Per Case Boylan Bottling Co Pure Seltzer, 12 760712112001 Boylan Ounce -- 24 Per Case Boylan Bottling Co Seasonal 760712561007 Boylan Sparkling Cider , 12 Ounce-24 Boylan Bottling Co Diet Root Beer 760712102002 Boylan Soda 12foz (pack Of 24) 760712812000 Boylan Boylan Mash - Lemon Peel & Ginger Root - 20 oz Plastic Bottles (15 Pack) Campbell Soup V8 Vegetable Juice, Original, 11.5 Fl 051000185600 Company Oz, 28 Ct Campbell Soup V-8 Splash, Berry Blend, 16oz Bottle, 051000146533 Company (12 pack) Campbell Soup V8 Splash Fruit Beverage, 16 Fl Oz 051000146632 Company (12 Pack) Campbell Soup V-8 Splash, Strawberry Kiwi, 16fl oz 051000146557 Company (12 pack) Campbell Soup V8 Splash, Tropical Blend, 16fl oz (12 051000146540 Company pack) Coca-Cola - Classic 33.80 fl oz or 1 049000005226 Coca-Cola liter (pack of 12) Minute Maid Fruit Punch 20 oz (pack 025000058028 Coca-Cola of 24) Minute Maid - Pink Lemonade 20.00 025000058868 Coca-Cola fl oz (pack of 24) Minute Maid Lemonade - 20 fl oz 025000058011 Coca-Cola (pack of 24) Coca Cola, Cherry Coke Zero 20.0 049000047547 Coca-Cola Oz. -

View Annual Report

7UP A&W AGUAFIEL BIG RED CANADA DRY CLAMATO COUNTRY TIME CRUSH DEJA BLUE DR PEPPER HAWAIIAN PUNCH IBC MISTIC MOTT’S MR AND MRS T NANTUCKET NECTARS PEÑAFIEL RC COLA REALEMON REALIME ROSE’S SCHWEPPES SN APPLE SQUIRT STEWART’S growingwithflavor DR PEPPER SNAPPLE GROUP 2009 ANNUAL REPORT SUNDROP SUNKIST SODA TAHITIAN TREAT VENOM ENERGY VERNORS WELCH’S YOO-HOO Our Leading Flavor Portfolio At Dr Pepper Snapple Group, we are growing with flavor — and what’s more, flavors are growing as a percentage of carbonated soft contents drinks (CSDs). Having gained steadily on colas over the past two decades, flavors took the letter to stockholders 1 lead in 2009 and now represent 50.4 percent leading with brands 5 of all CSD retail sales in measured channels. distribution and availability 8 FLAVORS AS % OF U.S. CSD SALES strengthening the foundation 11 commitment to csr 12 49.6% 54.0% stockholder information 139 54.6% 57.8% Colas 60.8% 50.4% 45.4% 46.0% Flavors 39.2% 42.2% On top of that, our CSDs outperformed the ’89 ’94 ’99 ’04 ’09 industry in both volume and dollar sales Source: Nielsen estimates in 2009, demonstrating the strength and resilience of our brands amid softness in the category. As the undisputed leader in flavors, Dr Pepper Snapple Group is capitalizing on this momentum. We now hold more % CHANGE VS. 2008 than a 40 percent dollar share of the flavor U.S. Volume Sales U.S. Dollar Sales category, up 1.7 percentage points in 2009. DPS +7.0% DPS 40.3% +4.2% 2009 Total CSDs 38.6% Total CSDs +0.8% 2008 -2.5% Source: The Nielsen Company +1.7% We invite you to experience a taste of our achievements and the ways in which DPS U.S.