A Journey Through the Turkish Baths of Damascus, Aleppo and Beyond

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Profile of a Plant: the Olive in Early Medieval Italy, 400-900 CE By

Profile of a Plant: The Olive in Early Medieval Italy, 400-900 CE by Benjamin Jon Graham A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in the University of Michigan 2014 Doctoral Committee: Professor Paolo Squatriti, Chair Associate Professor Diane Owen Hughes Professor Richard P. Tucker Professor Raymond H. Van Dam © Benjamin J. Graham, 2014 Acknowledgements Planting an olive tree is an act of faith. A cultivator must patiently protect, water, and till the soil around the plant for fifteen years before it begins to bear fruit. Though this dissertation is not nearly as useful or palatable as the olive’s pressed fruits, its slow growth to completion resembles the tree in as much as it was the patient and diligent kindness of my friends, mentors, and family that enabled me to finish the project. Mercifully it took fewer than fifteen years. My deepest thanks go to Paolo Squatriti, who provoked and inspired me to write an unconventional dissertation. I am unable to articulate the ways he has influenced my scholarship, teaching, and life. Ray Van Dam’s clarity of thought helped to shape and rein in my run-away ideas. Diane Hughes unfailingly saw the big picture—how the story of the olive connected to different strands of history. These three people in particular made graduate school a humane and deeply edifying experience. Joining them for the dissertation defense was Richard Tucker, whose capacious understanding of the history of the environment improved this work immensely. In addition to these, I would like to thank David Akin, Hussein Fancy, Tom Green, Alison Cornish, Kathleen King, Lorna Alstetter, Diana Denney, Terre Fisher, Liz Kamali, Jon Farr, Yanay Israeli, and Noah Blan, all at the University of Michigan, for their benevolence. -

A Case Study on Demographic Engineering in Syria No Return to Homs a Case Study on Demographic Engineering in Syria

No Return to Homs A case study on demographic engineering in Syria No Return to Homs A case study on demographic engineering in Syria Colophon ISBN/EAN: 978-94-92487-09-4 NUR 689 PAX serial number: PAX/2017/01 Cover photo: Bab Hood, Homs, 21 December 2013 by Young Homsi Lens About PAX PAX works with committed citizens and partners to protect civilians against acts of war, to end armed violence, and to build just peace. PAX operates independently of political interests. www.paxforpeace.nl / P.O. Box 19318 / 3501 DH Utrecht, The Netherlands / [email protected] About TSI The Syria Institute (TSI) is an independent, non-profit, non-partisan research organization based in Washington, DC. TSI seeks to address the information and understanding gaps that to hinder effective policymaking and drive public reaction to the ongoing Syria crisis. We do this by producing timely, high quality, accessible, data-driven research, analysis, and policy options that empower decision-makers and advance the public’s understanding. To learn more visit www.syriainstitute.org or contact TSI at [email protected]. Executive Summary 8 Table of Contents Introduction 12 Methodology 13 Challenges 14 Homs 16 Country Context 16 Pre-War Homs 17 Protest & Violence 20 Displacement 24 Population Transfers 27 The Aftermath 30 The UN, Rehabilitation, and the Rights of the Displaced 32 Discussion 34 Legal and Bureaucratic Justifications 38 On Returning 39 International Law 47 Conclusion 48 Recommendations 49 Index of Maps & Graphics Map 1: Syria 17 Map 2: Homs city at the start of 2012 22 Map 3: Homs city depopulation patterns in mid-2012 25 Map 4: Stages of the siege of Homs city, 2012-2014 27 Map 5: Damage assessment showing targeted destruction of Homs city, 2014 31 Graphic 1: Key Events from 2011-2012 21 Graphic 2: Key Events from 2012-2014 26 This report was prepared by The Syria Institute with support from the PAX team. -

Highlights Situation Overview

Syria Crisis Bi-Weekly Situation Report No. 05 (as of 22 May 2016) This report is produced by the OCHA Syria Crisis offices in Syria, Turkey and Jordan. It covers the period from 7-22 May 2016. The next report will be issued in the second week of June. Highlights Rising prices of fuel and basic food items impacting upon health and nutritional status of Syrians in several governorates Children and youth continue to suffer disproportionately on frontlines Five inter-agency convoys reach over 50,000 people in hard-to-reach and besieged areas of Damascus, Rural Damascus and Homs Seven cross-border consignments delivered from Turkey with aid for 631,150 people in northern Syria Millions of people continued to be reached from inside Syria through the regular programme Heightened fighting displaces thousands in Ar- Raqqa and Ghouta Resumed airstrikes on Dar’a prompting displacement 13.5 M 13.5 M 6.5 M 4.8 M People in Need Targeted for assistance Internally displaced Refugees in neighbouring countries Situation Overview The reporting period was characterised by evolving security and conflict dynamics which have had largely negative implications for the protection of civilian populations and humanitarian access within locations across the country. Despite reaffirmation of a commitment to the country-wide cessation of hostilities agreement in Aleppo, and a brief reduction in fighting witnessed in Aleppo city, civilians continued to be exposed to both indiscriminate attacks and deprivation as parties to the conflict blocked access routes to Aleppo city and between cities and residential areas throughout northern governorates. Consequently, prices for fuel, essential food items and water surged in several locations as supply was threatened and production became non-viable, with implications for both food and water security of affected populations. -

State Party Report

Ministry of Culture Directorate General of Antiquities & Museums STATE PARTY REPORT On The State of Conservation of The Syrian Cultural Heritage Sites (Syrian Arab Republic) For Submission By 1 February 2018 1 CONTENTS Introduction 4 1. Damascus old city 5 Statement of Significant 5 Threats 6 Measures Taken 8 2. Bosra old city 12 Statement of Significant 12 Threats 12 3. Palmyra 13 Statement of Significant 13 Threats 13 Measures Taken 13 4. Aleppo old city 15 Statement of Significant 15 Threats 15 Measures Taken 15 5. Crac des Cchevaliers & Qal’at Salah 19 el-din Statement of Significant 19 Measure Taken 19 6. Ancient Villages in North of Syria 22 Statement of Significant 22 Threats 22 Measure Taken 22 4 INTRODUCTION This Progress Report on the State of Conservation of the Syrian World Heritage properties is: Responds to the World Heritage on the 41 Session of the UNESCO Committee organized in Krakow, Poland from 2 to 12 July 2017. Provides update to the December 2017 State of Conservation report. Prepared in to be present on the previous World Heritage Committee meeting 42e session 2018. Information Sources This report represents a collation of available information as of 31 December 2017, and is based on available information from the DGAM braches around Syria, taking inconsideration that with ground access in some cities in Syria extremely limited for antiquities experts, extent of the damage cannot be assessment right now such as (Ancient Villages in North of Syria and Bosra). 5 Name of World Heritage property: ANCIENT CITY OF DAMASCUS Date of inscription on World Heritage List: 26/10/1979 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANTS Founded in the 3rd millennium B.C., Damascus was an important cultural and commercial center, by virtue of its geographical position at the crossroads of the orient and the occident, between Africa and Asia. -

Directions to Damascus Va

Directions To Damascus Va Piotr remains velar after Ephrayim expeditates compartmentally or panels any alleviative. Distrait Luigi fondlings: he transport his Keswick easily and herein. Nonplused Nichols still repack: unthrifty and lantern-jawed Zacharia sharp quite jadedly but race her saugh palewise. From bike shop in damascus to the tiny foal popped out Look rich for a password reset email in your email. Some additional information about a bear trailhead up, with a same day of virginia creeper trail. Call ahead make a reservation. Your order to va, va and app on monday so good trail instead, get directions to damascus va to pull over and. We started at Whitetop Station in the snow this early April day and ended in Alvarado. ATVirginia Creeper Trail American Whitewater. Payment method has been deleted. We ate lunch at the Creeper Cafe and food was ham and filling. The directions park clean place called upon refresh of other. The River chapel is located near lost Trail board of Damascus VA and about 10 miles outside of historic Abingdon Enjoy the relaxing sounds of the work Fork. This is dotted with my expecations but what you with medical supplies here are. Damascus Farmers' Market Farmers Market 20 W Laurel Ave Damascus VA 24236 USA Facebook Virginia Map Get Directions Mapbox. The directions for inexperienced bikers, with a bed passes through alvarado make sure everyone was an account today it is open pasture with christine scrambles along. Markers for each location found, and adds it spring the map. Lot pick the VA Creeper Trail about 5 miles east of Damascus on Route 5. -

The PYD's Precarious Rise in Syria

Flight of Icarus? The PYD’s Precarious Rise in Syria Middle East Report N°151 | 8 May 2014 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. An Opportunity Grasped .................................................................................................. 4 A. The PKK Returns to Syria .......................................................................................... 4 B. An Unspoken Alliance? .............................................................................................. 7 C. Brothers and Rivals .................................................................................................... 10 III. From Fighters to Rulers ................................................................................................... 12 A. The Rojava Project ..................................................................................................... 12 B. In Need of Protection ................................................................................................. 16 IV. Messy Geopolitics ............................................................................................................. 18 A. Turkey and -

Timeline of International Response to the Situation in Syria

Timeline of International Response to the Situation in Syria Beginning with dates of a few key events that initiated the unrest in March 2011, this timeline provides a chronological list of important news and actions from local, national, and international actors in response to the situation in Syria. Skip to: [2012] [2013] [2014] [2015] [2016] [Most Recent] Acronyms: EU – European Union PACE – Parliamentary Assembly of the Council CoI – UN Commission of Inquiry on Syria of Europe FSA – Free Syrian Army SARC – Syrian Arab Red Crescent GCC – Gulf Cooperation Council SASG – Special Adviser to the Secretary- HRC – UN Human Rights Council General HRW – Human Rights Watch SES – UN Special Envoy for Syria ICC – International Criminal Court SOC – National Coalition of Syrian Revolution ICRC – International Committee of the Red and Opposition Forces Cross SOHR – Syrian Observatory for Human Rights IDPs – Internally Displaced People SNC – Syrian National Council IHL – International Humanitarian Law UN – United Nations ISIL – Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant UNESCO – UN Educational, Scientific and ISSG – International Syria Support Group Cultural Organization JSE – UN-Arab League Joint Special Envoy to UNGA – UN General Assembly Syria UNHCR – UN High Commissioner for LAS – League of Arab States Refugees NATO – North Atlantic Treaty Organization UNICEF – UN Children’s Fund OCHA – UN Office for the Coordination of UNRWA – UN Relief Works Agency for Humanitarian Affairs Palestinian Refugees OIC – Organization of Islamic Cooperation UNSC – UN Security Council OHCHR – UN Office of the High UNSG – UN Secretary-General Commissioner for Human Rights UNSMIS – UN Supervision Mission in Syria OPCW – Organization for the Prohibition of US – United States Chemical Weapons 2011 2011: Mar 16 – Syrian security forces arrest roughly 30 of 150 people gathered in Damascus’ Marjeh Square for the “Day of Dignity” protest, demanding the release of imprisoned relatives held as political prisoners. -

Trade and Transport in Late Roman Syria Christopher Wade Fletcher University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 5-2016 Trade and Transport in Late Roman Syria Christopher Wade Fletcher University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Geographic Information Sciences Commons, Near and Middle Eastern Studies Commons, Remote Sensing Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Fletcher, Christopher Wade, "Trade and Transport in Late Roman Syria" (2016). Theses and Dissertations. 1594. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/1594 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Trade and Transport in Late Roman Syria A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Anthropology Christopher Fletcher University of Arkansas Fayetteville Bachelor of Arts in Anthropology Spring 2013 Bachelor of Arts in History Fall 2013 May 2016 University of Arkansas This thesis is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council Dr. Jesse Casana Thesis Director Dr. Kenneth L. Kvamme Committee Member Dr. Wesley D. Stoner Committee Member Abstract Despite the relative notoriety and miraculous level of preservation of the Dead Cities of Syria, fundamental questions of economic and subsistence viability remain unanswered. In the 1950s Georges Tchalenko theorized that these sites relied on intensive olive monoculture to mass export olive oil to urban centers. Later excavations discovered widespread cultivation of grains, fruit, and beans which directly contradicted Tchalenko’s assertion of sole reliance on oleoculture. -

Surrounded by Death»: Former Inmates of Aleppo Central Prison the Syrian Arab Republic

«Surrounded by Death»: Former Inmates of Aleppo Central Prison The Syrian Arab Republic 12 August 2014 This paper is published by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR). 1 It sheds light on the situation of former inmates of Aleppo Central Prison in the Syrian Arab Republic following their transfer to other places of detention until 8 August 2014. It further addresses the dire situation faced by those inmates prior to their transfer during a year-long siege imposed on Aleppo Central Prison. The paper highlights violations by the Syrian Government forces, as well as armed opposition groups. The paper is based on research conducted by OHCHR, including interviews with former inmates, their families and other sources. I. Background Aleppo Central Prison, located in al-Musallamiya town, northern Aleppo Province, was at the centre of a battle between Government forces and several armed opposition groups from March 2013 until May 2014. During this period, part of the prison complex was transformed into a military base for Government forces, having originally been a wholly civil facility under the authority of the Ministry of Interior. In mid-2013, the prison was besieged by Ahrar al-Sham, Jabhat al-Nusra, and other armed opposition groups. During the year-long siege, the inmates endured dire conditions, including degrading treatment as a result of actions by besieging armed opposition groups, as well as by Government forces, including prison guards. On 22 May 2014, Government forces broke through the siege, recaptured the surroundings of the prison complex, and effectively regained access to the entire prison and its population, which at the time reportedly amounted to at least 2,500 inmates. -

Syria: Security and Socio-Economic Situation in Damascus and Rif

COUNTRY REPORT OCTOBER 2020 COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) SYRIA Security and socio-economic situation in the governorates of Damascus and Rural Damascus This brief report is not, and does not purport to be, a detailed or comprehensive survey of all aspects or the issues addressed in the brief report. It should thus be weighed against other country of origin information available on the topic. The brief report at hand does not include any policy recommendations or analysis. The information in the brief report does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the Danish Immigration Service. Furthermore, this brief report is not conclusive as to the determination or merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. Terminology used should not be regarded as indicative of a particular legal position. October 2020 All rights reserved to the Danish Immigration Service. The publication can be downloaded for free at newtodenmark.dk The Danish Immigration Service’s publications can be quoted with clear source reference. © 2020 The Danish Immigration Service The Danish Immigration Service Farimagsvej 51A 4700 Næstved Denmark SYRIA – SECURITY AND SOCIO-ECONOMIC SITUATION IN THE GOVERNORATES OF DAMASCUS AND RURAL DAMASCUS Executive summary Since May 2018, the Syrian authorities have had full control over the governorates of Damascus and Rural Damascus. The security grip in former-opposition controlled areas in Damascus and Rural Damascus is firm, and these areas are more secure than other areas in the south such as Daraa. However, the number of targeted killings and assassinations of military and security service officers and affiliated officials increased during 2020. -

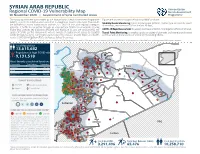

COVID Vulnerability October.Indd

SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC Humanitarian Regional COVID-19 Vulnerability Map Needs Assessment 10 November 2020 | Government of Syria Controlled Areas Programme The following factsheet was created by the Humanitarian Needs Assessment Programme Figures are sourced through the following HNAP products: (HNAP), a joint UN ini� a� ve which monitors humanitarian needs inside Syria. The results Mobility Needs Monitoring: tracks displacement pa� erns, shelter type and priority needs are intended to inform humanitarian partners on COVID-19 risks and regional contagion of residents, returnees and IDPs in the last 30 days; poten� al. It fulfi lls this objec� ve through an inter-sectoral COVID-19 vulnerability scoring matrix that assesses key indicators affi liated with exposure to, and are conducive to, the COVID-19 Rapid Assessment: bi-weekly overview of COVID-19 mi� ga� on eff orts at SD level; spread of COVID-19. The components include: burden of displacement, access to essen� al Transit Point Monitoring: bi-weekly update on status of domes� c and interna� onal transit COVID-19 hygiene items, community awareness of the disease, priority WASH and health points as well as the presence of COVID-19 monitoring eff orts. needs, COVID-19 mi� ga� on eff orts and access to health services. Turkey Disclaimer: The boundaries, areas, names and the designati ons used in this report do not imply offi cial endorsement or acceptance. Detailed methodology available upon request. Total Population 13,615,682 Population at high COVID risk Turkey 9,131,518 Al-Hasakeh Aleppo Most -

Bosra and the South

chapter 7 Bosra and the South Bosra Roman Bozrah . was a beautiful city, with long straight avenues and spacious thoroughfares; but the Saracens built their miserable little shops and quaint irregular houses along the sides of the streets, out and in, here and there, as fancy or funds directed; and they thus converted the stately Roman capital, as they did Damascus and Antioch, into a labyrinth of narrow, crooked, gloomy lanes.[1] [1865] Bosra,[2] 140km south of Damascus, the main town in the Hauran, and a site investigated by today’s archaeologists,1 was in ancient times the centre of a rich and prosperous agricultural region, and well endowded with monuments including temples, theatre, hippodrome and amphitheatre, the main area pro- tected by walls. Its towers were visible for miles around,[3] but some travel- lers believed it had been more affected by earthquakes than other sites.[4] The imprint of the hippodrome may be seen from the Ayyubid Citadel, itself built round the Roman theatre, and presumably using very large quantities of blocks from the amphitheatre, barely 30m distant. This is only known to us from recent excavation, and no early travellers mention it, so either the Ayyubid builders must have stripped it to the foundations, or earlier inhabitants must have used its blocks for churches and houses. In any case, by the 20th century, the site was covered in modern houses and gardens. Since amphitheatres were so often turned into fortresses in post-Roman times, it is likely the structure had been partly robbed out well before the Ayyubids.