Year Two Evaluation of the LA's BEST After School Arts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KTX: a Success Story Amidst Lockdown, Shutdown Story on Page 4

MARCH 2021 A monthly publication of the Lopez group of companies www.lopezlink.ph http://www.facebook.com/lopezlinkonline www.twitter.com/lopezlinkph Economic impact assessment KTX: A success story amidst lockdown, shutdown Story on page 4 Golden Arrows for The Grove LPZ, ABS-CBN opens up & First Gen …page 3 …page 7 ‘Justice’ is served …page 8 2 Lopezlink March 2021 BIZ NEWS BIZ NEWS Lopezlink March 2021 3 ‘Full steam ahead’ SKY Fiber offers leveled up speeds Exec Movements Three Lopez companies bag Golden Arrow awards EDC launches Green Bond at the same affordable rates FPH greenlights Framework on its 45th anniversary NEW and existing SKY Fiber By Dolly Pasia-Ramos By Frances Ariola subscribers can quickly enhance their productivity and lifestyle appointment Bond Shelf Registration of up and evaluation of the projects, when they maximize SKY Fi- to P15 billion, and the offer and the management of the pro- ber’s leveled up fiber-fast home issuance of an initial tranche of ceeds of the Green Bonds, and internet subscription plans that of Mayol as VP up to P3 billion with an over- subsequent reporting. are even more affordably priced LPZ VP-legal and compliance officer Atty. Maria Amina Amado and risk subscription option of up to P2 Sustainalytics has reviewed than before. THE board of directors management head Carla Paras-Sison billion fixed rate bonds, subject to and issued a Second-Party A P999 monthly fee can now of First Philippine Hold- the approval of the Securities and Opinion on EDC’s Green Bond get subscribers up to 20 Mbps, ings Corporation (FPH) on Exchange Commission (SEC), to Framework. -

Pt.BI ISHTAR ~IKAIBKRS

ASCAP "S 2006 DART CLADI Pt.BI ISHTAR ~IKAIBKRS WiD AFFILIATED FOREIG& SOCIETIKS 3 OLC&IE I OF III P U B L I S H E R .357 PUBLISHING (A) S1DE UP MUSIC $$ FAR BEYOND ENTERTAINMENT $3.34 CHANGE OF THE BEAST ? DAT I SMELL MUS1C 'NANA PUDDIN PUBL1SHING A & N MUSIC CORP A & R MUSIC CO A A B A C A B PUBLISH1NG A A KLYC 4 A A P PUBLISHING A AL1KE PUBLiSHING A ALIKES MUSIC PUBLISHING A AND F DOGZ MUSIC A AND G NEALS PUBLiSHER A AND L MUS1C A AND S MUSICAL WORKS AB& LMUSIC A B A D MUZIC PUBLISHING A B ARPEGGIO MUSIC ABCG I ABCGMUSIC A B GREER PUBLISH1NG A B REAL MUSIC PUBLISHING A B U MUSIC A B WILLIS MUS1C A BAGLEY SONG COMPANY A BALLISTIC MUSIC A BETTER HISTORY PUBLISH1NG A BETTER PUBL1SHING COMPANY A BETTER TOMORROM A BIG ATT1TUDE INC A BIG F-YOU TO THE RHYTHM A BILL DOUGLAS MUSIC A BIRD AND A BEAR PUBLISHING A BLACK CLAN 1NC A BLONDE THING PUBLISHING A BOCK PUBLISHING A BOMBINATION MUSIC A BOY AND HIS DOG A BOY NAMED HO A BRICK CALLED ALCOHOL MUSIC A BROOKLYN PROJECT A BROS A BUBBA RAMEY MUSIC A BURNABLE PUBLISHING COMPANY A C DYENASTY ENT A CARPENTER'S SON A CAT NAMED TUNA PUBLISHING A CHUNKA MUSIC A CIRCLE OF FIFTHS MUSIC A CLAIRE MlKE MUSIC A CORDIS MUSIC A CREATI VE CHYLD ' PUB L I SHING A CREATIVE RHYTHM A CROM FLIES MUSIC INC A .CURSIVE MEMDR1ZZLE A D D RECORDiNGS A D G MUSICAL PUBLISHING INC A D HEALTHFUL LIFESTYLES A D SIMPSON OWN A D SMITH PUBLISHING P U B L I S H E R A D TERROBLE ENT1RETY A D TUTUNARU PUBLISHING A DAISY IN A JELLYGLASS A DAY XN DECEMBER A DAY XN PARIS MUSIC A DAY W1TH KAELEY CLAIRE A DELTA PACIFIC PRODUCTION A DENO -

Phonographic Performance Company of Australia Limited Control of Music on Hold and Public Performance Rights Schedule 2

PHONOGRAPHIC PERFORMANCE COMPANY OF AUSTRALIA LIMITED CONTROL OF MUSIC ON HOLD AND PUBLIC PERFORMANCE RIGHTS SCHEDULE 2 001 (SoundExchange) (SME US Latin) Make Money Records (The 10049735 Canada Inc. (The Orchard) 100% (BMG Rights Management (Australia) Orchard) 10049735 Canada Inc. (The Orchard) (SME US Latin) Music VIP Entertainment Inc. Pty Ltd) 10065544 Canada Inc. (The Orchard) 441 (SoundExchange) 2. (The Orchard) (SME US Latin) NRE Inc. (The Orchard) 100m Records (PPL) 777 (PPL) (SME US Latin) Ozner Entertainment Inc (The 100M Records (PPL) 786 (PPL) Orchard) 100mg Music (PPL) 1991 (Defensive Music Ltd) (SME US Latin) Regio Mex Music LLC (The 101 Production Music (101 Music Pty Ltd) 1991 (Lime Blue Music Limited) Orchard) 101 Records (PPL) !Handzup! Network (The Orchard) (SME US Latin) RVMK Records LLC (The Orchard) 104 Records (PPL) !K7 Records (!K7 Music GmbH) (SME US Latin) Up To Date Entertainment (The 10410Records (PPL) !K7 Records (PPL) Orchard) 106 Records (PPL) "12"" Monkeys" (Rights' Up SPRL) (SME US Latin) Vicktory Music Group (The 107 Records (PPL) $Profit Dolla$ Records,LLC. (PPL) Orchard) (SME US Latin) VP Records - New Masters 107 Records (SoundExchange) $treet Monopoly (SoundExchange) (The Orchard) 108 Pics llc. (SoundExchange) (Angel) 2 Publishing Company LCC (SME US Latin) VP Records Corp. (The 1080 Collective (1080 Collective) (SoundExchange) Orchard) (APC) (Apparel Music Classics) (PPL) (SZR) Music (The Orchard) 10am Records (PPL) (APD) (Apparel Music Digital) (PPL) (SZR) Music (PPL) 10Birds (SoundExchange) (APF) (Apparel Music Flash) (PPL) (The) Vinyl Stone (SoundExchange) 10E Records (PPL) (APL) (Apparel Music Ltd) (PPL) **** artistes (PPL) 10Man Productions (PPL) (ASCI) (SoundExchange) *Cutz (SoundExchange) 10T Records (SoundExchange) (Essential) Blay Vision (The Orchard) .DotBleep (SoundExchange) 10th Legion Records (The Orchard) (EV3) Evolution 3 Ent. -

Icon La Catalog Archive

Catalog for 2020 begins after addenda LOS ANGELES LOS ANGELES CAMPUS PROGRAMS 2020 ADDENDA AND CATALOG Effective August 20, 2020 4620 West Magnolia Boulevard | Burbank CA 91505 | (818) 299 8013 | iconcollective.com This supersedes information contained in the 2020 catalog Veteran’s Benefits- page 24 ICON’s 12-month Los Angeles Music Production Program, Advanced Music Production Program: Los Angeles, and Vocal Artist Program: Los Angeles are approved for veteran benefits including GI Bill®, by the California State Approving Agency for Veterans (CSAAVE). The Music Business Program: Los Angeles is not approved for benefits at this time. Notice of COVID-19 policies Icon Collective is committed to taking all reasonable steps to protect the health of its personnel and students during the unprecedented coronavirus disease (“COVID-19”) pandemic. COVID-19 INHERENT RISKS. According to the Centers for Disease Control (“CDC”), COVID-19, is a respiratory illness thought to spread mainly between people who are in proximity with one another, through respiratory droplets produced when an infected person coughs, sneezes, talks, or merely breathes, that can land in the mouths or noses of people who are nearby or possibly be inhaled into the lungs. It is widely known that people with mild or even no symptoms may be able to spread the virus. The virus that causes COVID-19 spreads very easily and sustainably between people. Information from the CDC indicates this virus is more contagious than influenza (the flu), which is itself highly contagious. The CDC also advises a person may contract the virus that causes COVID-19 by touching a surface or object that has the virus on it and then touching their own mouth, nose, or eyes. -

Duterte Says Money Is Found and All Fillipinos Will Be Vaccinated 1 1 Honey Shot She Sings, She Dances, She Composes Songs

NOVEMBER 2020 L is for Rabbit DepEd Online modules with questions like “How do Airplanes Sound” confuses mom and baffles Broadway actress and singer Lea Salonga PHILIPPINES - Everyone seems to deal with confusing learning modules. module because it asked this question: reposted online almost 18,000 times, be struggling with blended learning, Last month, a parent named what do airplanes sound like? including parents who have had to Kristine Joy Rivera posted her child’s The questionnaire, which has been L IS FOR RABBIT continued on page 25 Nostalgia HEAVEN CARRIEDO STREET, MANILA 1960’S Peralejo Happy to be the Philippines starts lead in national ID cards a new Government hopes system will spur consumer adoption of electronic payments series The planned Philippine ID system could accelerate adoption of electronic payments in the Southeast Asian country. MANILA-The Philippines without bank accounts to began registering millions access financial services. of citizens for its national All Philippine citizens identification system, hop- and resident foreigners are ing to promote electronic required to register such payments and make it eas- NATIONAL ID ier for low-income earners on page 26 UK TO DONATE TO TYPHOON RELIEF Gov’t clears Duterte’s Typhoon Absence Calida trying to unseat SC Leonen Andi Eigenmann’s Simple Life Why No Designer Stuff for Danica Sotto MANILA, Philippines — The Supreme Court should thwart Senate Minority Leader Solicitor General Jose Calida’s effort to repeat history by unseating Franklin Drilon said Calida’s No Nudity for Phoebe Walker Associate Justice Marvic Leonen through his wealth declaration CALIDA statements or the lack of it, a Senate leader said on Sunday. -

President Manny Pacquiao Dizon

JANUARY 2021 President Manny Pacquiao It can and It may Happen, as Pacquiao takes over as president of Duterte’s PDP-Laban MANILA - For now, president of Duterte. Boxer-turned-senator Pacquiao of the Party to one with new, ‘mod- PDP-Laban. The oathtaking ceremony took replaced Sen. Aquilino “Koko” Pi- ern’ ideas and one who has the time, As the 2022 elections draw nearer, place December 2, 2019, with House mentel III, who will now serve as the energy, and boldness to prepare the Sen. Manny Pacquiao was sworn in as Speaker Lord Allan Velasco also party’s executive vice chairman. the new president of PDP-Laban, the taking his oath as the party’s new “Senator Koko Pimentel has passed PRESIDENT PACQUIAO political party of President Rodrigo executive president. on the practical day-to-day leadership continued on page 21 Look Back Real Session Road, Baguio 1960’S Fan Girl beats veterans for Best Filipino health workers in the frontline of Actress vaccine history Award TORONTO - On the showing “light at the end opposite sides of the of the tunnel.” Atlantic, one was admin- Filipino nurse May istering it, the other was Parsons delivered Pfiz- for role in receiving it. er-BioNTech’s coronavirus ‘Now it feels like there vaccine to 90-year-old is light at the end of the Margaret Keenan at a tunnel,’ says Filipino local hospital in Coventry. Fan Girl nurse May Parsons, who Keenan is the first person has been working with in world to get the vac- the UK’s National Health cine, approved just a week Service for 24 years ago in Britain. -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Mediating Global Filipinos: The Filipino Channel and the Filipino Diaspora Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8jh604ks Author Lu, Ethel Regis Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Mediating Global Filipinos: The Filipino Channel and the Filipino Diaspora By Ethel Marie P. Regis A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnic Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Catherine Ceniza Choy, Chair Professor Elaine H. Kim Professor Khatharya Um Professor Irene Bloemraad Fall 2013 Abstract Mediating Global Filipinos: The Filipino Channel and the Filipino Diaspora by Ethel Marie P. Regis Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnic Studies University of California, Berkeley Professor Catherine Ceniza Choy, Chair Mediating Global Filipinos: The Filipino Channel and the Filipino Diaspora examines the notion of the “global Filipino” as imagined and constructed vis-à-vis television programs on The Filipino Channel (TFC). This study contends that transnational Philippine media broadly construct the notion of “global Filipinos” as diverse, productive, multicultural citizens, which in effect establishes a unified overseas Filipino citizenry for Philippine economic Welfare and global cultural capital. Despite the netWork’s attempts at representing difference and inclusion, what the notion of “global Filipinos” does not address are the structural and social inequities that affect the everyday lives Filipino diasporans and the Ways in Which immigrants and second generation Filipino Americans alike carefully negotiate family ties and the politics of their changing identities and commitments. -

Download Our Free Listings App - APPENING on the Apple and Android Stores

Issue 08 2021 www.gpv.is New Wave 3 Men, 1 North LGBT(heatre) Reykjanes! News: Not the !ood kind, the Culture: The Grapevine's Art: Queer teens take to the Travel: It's not just for pandemic kind Frin!e Award winners streets! volcanos anymore Being Nonbinary, In Iceland And Everywhere Nonbinary people have always existed, all over the world, but are only recently getting noticed in Eurocentric coun- tries. We explore what being nonbinary means, the challenges they face, and what needs to change for the better. COVER ART: Photo by Art Bicnick. On the cover: Ari Logn, Regn and Reyn, three nonbinary Icelanders, enrobed in a nonbinary pride flag. 06: COVID Strikes Back 20: Queer Teens Werk It 31: Reykjanes Revelry 06: Saga's Turning Blue 11: MEN OF THE NORTH 27: Style Straight From 07: Nordic Gods & Finnish RISE UP AND JUGGLE The Non-Straights First Rock Gods 24: Mannveira... \m/ 26: Saga Cowboy EDITORIAL Andie Sophia Will Not Shut Up Hannah Jane’s Sentimental Sermon A recent comment on one of our YouTube videos complained Last year, Andie Sophia and I wrote our joint Pride editorial that I should shut up about being trans and nonbinary; that at the tail end of the widespread Black Lives Matter protests. it’s in fact straight cis people who are actually marginalised, I remember sitting at this same desk thinking that the hatred and “freaks” like me are taking over. gripping our shared birth country couldn’t possibly get more extreme. If you had told me that in months, insurrectionists There’s an old saying that goes: “when you’re accustomed to would storm our Capital Building encouraged by our then- privilege, equality feels like oppression.” I would argue that President, I would not have believed you. -

Philippines in View Cc

PHILIPPINES IN VIEW 2021 Table of Contents Chapter 1: Overall TV Market Environment ........................................................................ 2 Chapter 2: Online Curated Content (OCC) Market Environment ....................................... 13 Chapter 3: Traditional Pay TV Market Environment ......................................................... 45 Chapter 4: Piracy in the Philippines: Piracy and Unauthorized Distribution for Online and Traditional TV .................................................................................................................. 97 Chapter 5: Regulatory Environment for Digital Content ........................................................ 102 References ..................................................................................................................... 113 Annex A: Top TV Programs ............................................................................................. 121 Annex B: Glossary of Acronyms ...................................................................................... 125 1 Chapter 1: Overall TV Market Environment The disruptions to the Philippine television (TV) industry over recent years are many and the most recent of them, the 2019 coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19), has not made things easier. In June 2020, the World Economic Forum cited the myriad ways the pandemic has affected the media industry from content creators to distributors, saying that while consumer demand for content has skyrocketed due to lockdowns and the prevalence of remote -

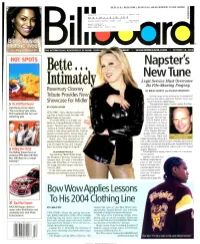

Bette... New Tune R Legit Service Must Overcome Intimately Its File -Sharing Progeny

$6.95 (U.S.), $8.95 (CAN.), £5.50 (U.K.), 8.95 (EUROPE), Y2,500 (JAPAN) 3 -DIGIT 908 #BCNCCVR * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * ** 111I111I111I1111I1H 1I111I11I111I111III111111II111I1 u A06 80101 #90807GEE374EM002# BLBD 508 001 MAR 04 2 MONTY GREENLY 3740 ELM AVE # A LONG BEACH CA 90807 -3402 Black Music' Historic Wee See Pages 20 and 58 THE INTERNATIONAL NEWSWEEKLY OF MUSIC, VIDEO A MENT www.billboard.com OCTOBER 18, 2003 HOT SPOTS Napster's Bette... New Tune r Legit Service Must Overcome Intimately Its File -Sharing Progeny Rosemary Clooney BY BRIAN GARRITY and JULIANA KORANTENG Tribute Provides New On the verge of resurfacing as a commercial service, the once -notorious Napster must face Showcase For Midler its own double -edged legacy. 5 The DVD That Roared The legitimate digital music market that Nap - helped force into Walt Disney Home Video's BY CHUCK TAYLOR ster existence is poised "The Lion Kng" gets deluxe NEW YORK -Barry Manilow recalls wak- to go mainstream in DVD treatment and two -year ing from a dream earlier this year with North America and plan. marketing Bette Midler on his mind. Europe. Yet the maj- "It was the 1950s in my dream, and ority of digital music Bette wa: singing Rosemary Clooney consumers in those songs," Manilow says with a smile. territories continue to "Bette and I hadn't spoken in years, but I get their music for free picked u- the phone and told her I had an from Napster -like peer- i idea for a tribute album. I knew there was to -peer (P2P) networks. absolutely no one else who could do this." In Europe, legal and GOROG: GIVING CONSUMERS WHATTHEY WANT Midle- says, "The concept was ab- illegal downloads are on the solutely billiant. -

Devotional and Workout Edition (7 January 2013) to Mom and Dad for Living Your Faith in Our Hectic Family Business with Humility and Commitment to Christ

Devotional and Workout Edition (7 January 2013) To Mom and Dad for living your faith in our hectic family business with humility and commitment to Christ. Your practical and faithful witness prepared me for Life! To Mark Thompson, my first mentor in Christ, for lovingly challenging my „personal theology‟ by asking, “Where do you see that in God‟s Word?” Your gentle confrontation inspired me to begin a lifelong quest for Truth in God‟s Word. To Wes Alford, my college and seminary roommate and dear friend, for your authentic passion for Truth, music, laughter, family and even bean dip! ROFL!! You inspired me to live for Jesus every moment. Anything less is just religion. To Tom Waynick, Jeff Voyles and Stephen Muse, mentors in counseling and mindfulness, for lovingly nudging my closed mind and self-protected heart until I could no longer remain as I was. And when I began to unravel, you stayed with me to begin a glorious new journey that I hope will never end. To Dan Rose, counselor to my wife and I, during one of the toughest years of our lives. You helped us hear our love for each other on the other side of our fears. God used you to bring a greater depth and joy to our marriage. To Jae Park, Shon Severns, and Jeff Zust - friends and co-workers who provided helpful specific feedback on earlier versions for greater clarity & practicality. And to my Lauren. There are not enough words. My eyes still tear up that “I am my beloved‟s and my beloved is mine”. -

Affiliate9 Poreign Societies Voluaa 1 of 2 P U B L I S H E R

AS CAP ASCAP'S 2005 BART CLAIM PUBLISHER. MEMBERS.AND AFFILIATE9 POREIGN SOCIETIES VOLUAA 1 OF 2 P U B L I S H E R . 357 PUBLISHING (A) SIDE UP MUS1C $$ FAR BEYOND ENTERTAINMENT $3.34 CHANGE OF THE BEAST ? DAT I SMELL MUSIC 'NANA PUDD1N PUBLISHING A & N MUSIC CORP A & R MUSIC CO A A B A C A B PUBL1SHING A A KLYC 4 A A P PUBLISHING A ALIKE PUBLISHING A ALIKES MUSIC PUBLISHING A AND S MUSICAL WORKS A B & L MUS1C A B A D MUZZC PUBLISHING A B ARPEGGIO MUSIC A B GREER PUBLiSHING A B REAL MUSIC PUBLISHING A 8 U MUSiC A BAGLEY SONG COMPANY A BALLISTlc MUSIC A BETTER PUBLISHING COMPANY A BETTER TOMORROW A BIG ATTITUDE 1NC A BIG F-YOU TO THE RHYTHM A BIRD AND A BEAR PUBLISHING A BLACK CLAN INC A BLONDE TH1NG PUBLISHING A BOCK PUBLISHING A BOY AND HIS DOG A BOY NAMED HO A BROOKLYN PROIJECT A BROS A BUBBA RAMEY MUSlC A BURNABLE PUBLISHING COMPANY A C DYENASTY ENT A CAT NAMED TUNA PUBLISHING A CHUNKA MUS1C A CIRCLE OF FIFTHS MUSIC A CLAIRE M1KE MUSIC A CORDZS MUSIC A CREATIVE CHYLD ' PUBLISHING A CREATIVE RHYTHM A CROM FLIES MUSIC INC A D C Ii PRODUCTIONS A D D RECORDINGS A D G MUSICAL PUBLISHING ZNC A D HEALTHFUL LZFESTYLES A D SIMPSON OWN A DAISY 1N A 1JELLYGLASS A DAY IN DECEMBER A DAY IN PARIS MUSZC A DELTA PACIFIC PRODUCTION A DEMO DEVELOPMENT A DISC PUBLISHING A DIV1NE STRENGTH PRODUCTION A DOG NAMED KITTY PUBL1SHING A DOOKIE FONTANE EST A DOT P DOT MUS1C A DOUBLE MUSIC A DRUMMER'S LIFE P U 8 L I S H E R A DRUMMERS BEAT PUBLISHING A E AND M MUSIC A E E PRODUCTION PUBLZSHZNG A E G PUBLISHING A F B A FOUNDATION BUILDS A F ENLISTED WIDOWS HOME