New Exhibit Training Information Packet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North America Other Continents

Arctic Ocean Europe North Asia America Atlantic Ocean Pacific Ocean Africa Pacific Ocean South Indian America Ocean Oceania Southern Ocean Antarctica LAND & WATER • The surface of the Earth is covered by approximately 71% water and 29% land. • It contains 7 continents and 5 oceans. Land Water EARTH’S HEMISPHERES • The planet Earth can be divided into four different sections or hemispheres. The Equator is an imaginary horizontal line (latitude) that divides the earth into the Northern and Southern hemispheres, while the Prime Meridian is the imaginary vertical line (longitude) that divides the earth into the Eastern and Western hemispheres. • North America, Earth’s 3rd largest continent, includes 23 countries. It contains Bermuda, Canada, Mexico, the United States of America, all Caribbean and Central America countries, as well as Greenland, which is the world’s largest island. North West East LOCATION South • The continent of North America is located in both the Northern and Western hemispheres. It is surrounded by the Arctic Ocean in the north, by the Atlantic Ocean in the east, and by the Pacific Ocean in the west. • It measures 24,256,000 sq. km and takes up a little more than 16% of the land on Earth. North America 16% Other Continents 84% • North America has an approximate population of almost 529 million people, which is about 8% of the World’s total population. 92% 8% North America Other Continents • The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of Earth’s Oceans. It covers about 15% of the Earth’s total surface area and approximately 21% of its water surface area. -

Sea-Level Rise for the Coasts of California, Oregon, and Washington: Past, Present, and Future

Sea-Level Rise for the Coasts of California, Oregon, and Washington: Past, Present, and Future As more and more states are incorporating projections of sea-level rise into coastal planning efforts, the states of California, Oregon, and Washington asked the National Research Council to project sea-level rise along their coasts for the years 2030, 2050, and 2100, taking into account the many factors that affect sea-level rise on a local scale. The projections show a sharp distinction at Cape Mendocino in northern California. South of that point, sea-level rise is expected to be very close to global projections; north of that point, sea-level rise is projected to be less than global projections because seismic strain is pushing the land upward. ny significant sea-level In compliance with a rise will pose enor- 2008 executive order, mous risks to the California state agencies have A been incorporating projec- valuable infrastructure, devel- opment, and wetlands that line tions of sea-level rise into much of the 1,600 mile shore- their coastal planning. This line of California, Oregon, and study provides the first Washington. For example, in comprehensive regional San Francisco Bay, two inter- projections of the changes in national airports, the ports of sea level expected in San Francisco and Oakland, a California, Oregon, and naval air station, freeways, Washington. housing developments, and sports stadiums have been Global Sea-Level Rise built on fill that raised the land Following a few thousand level only a few feet above the years of relative stability, highest tides. The San Francisco International Airport (center) global sea level has been Sea-level change is linked and surrounding areas will begin to flood with as rising since the late 19th or to changes in the Earth’s little as 40 cm (16 inches) of sea-level rise, a early 20th century, when climate. -

NSF 03-021, Arctic Research in the United States

This document has been archived. Home is Where the Habitat is An Ecosystem Foundation for Wildlife Distribution and Behavior This article was prepared The lands and near-shore waters of Alaska remaining from recent geomorphic activities such by Page Spencer, stretch from 48° to 68° north latitude and from 130° as glaciers, floods, and volcanic eruptions.* National Park Service, west to 175° east longitude. The immense size of Ecosystems in Alaska are spread out along Anchorage, Alaska; Alaska is frequently portrayed through its super- three major bioclimatic gradients, represented by Gregory Nowacki, USDA Forest Service; Michael imposition on the continental U.S., stretching from the factors of climate (temperature and precipita- Fleming, U.S. Geological Georgia to California and from Minnesota to tion), vegetation (forested to non-forested), and Survey; Terry Brock, Texas. Within Alaska’s broad geographic extent disturbance regime. When the 32 ecoregions are USDA Forest Service there are widely diverse ecosystems, including arrayed along these gradients, eight large group- (retired); and Torre Arctic deserts, rainforests, boreal forests, alpine ings, or ecological divisions, emerge. In this paper Jorgenson, ABR, Inc. tundra, and impenetrable shrub thickets. This land we describe the eight ecological divisions, with is shaped by storms and waves driven across 8000 details from their component ecoregions and rep- miles of the Pacific Ocean, by huge river systems, resentative photos. by wildfire and permafrost, by volcanoes in the Ecosystem structures and environmental Ring of Fire where the Pacific plate dives beneath processes largely dictate the distribution and the North American plate, by frequent earth- behavior of wildlife species. -

Subregional and Regional Approaches for Disaster Resilience

United Nations ESCAP/76/14 Economic and Social Council Distr.: General 3 March 2020 Original: English Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific Seventy-sixth session Bangkok, 21 May 2020 Item 5 (d) of the provisional agenda* Review of the implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development in Asia and the Pacific: disaster risk reduction Subregional and regional approaches for disaster resilience Note by the secretariat Summary As climate uncertainties grow, Asia and the Pacific faces an increasingly complex disaster riskscape. In the Asia-Pacific Disaster Report 2019: The Disaster Riskscape across Asia-Pacific – Pathways for Resilience, Inclusion and Empowerment, the Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific provided a comprehensive overview of the regional riskscape, identifying the region’s main hotspots and options for action. Based on the findings, the present document contains highlights of the changing geography of disasters together with the associated multi-hazard risk hotspots at the subregional level, namely, South-East Asia, South and South-West Asia, the Pacific small island developing States, North and Central Asia, and North and East Asia. For each subregion, the document provides specific solution-oriented resilience-building approaches. In this regard, the document contains information about the opportunities to build resilience provided by subregional and regional cooperation and a discussion of the secretariat’s responses under the aegis of the Asia-Pacific Disaster Resilience Network. The Commission may wish to review the present document and provide guidance for the future work of the secretariat. I. Introduction 1. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development provides a blueprint for development, including ending poverty, fighting inequalities and tackling climate change. -

Giant Pacific Octopus (Enteroctopus Dofleini) Care Manual

Giant Pacific Octopus Insert Photo within this space (Enteroctopus dofleini) Care Manual CREATED BY AZA Aquatic Invertebrate Taxonomic Advisory Group IN ASSOCIATION WITH AZA Animal Welfare Committee Giant Pacific Octopus (Enteroctopus dofleini) Care Manual Giant Pacific Octopus (Enteroctopus dofleini) Care Manual Published by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums in association with the AZA Animal Welfare Committee Formal Citation: AZA Aquatic Invertebrate Taxon Advisory Group (AITAG) (2014). Giant Pacific Octopus (Enteroctopus dofleini) Care Manual. Association of Zoos and Aquariums, Silver Spring, MD. Original Completion Date: September 2014 Dedication: This work is dedicated to the memory of Roland C. Anderson, who passed away suddenly before its completion. No one person is more responsible for advancing and elevating the state of husbandry of this species, and we hope his lifelong body of work will inspire the next generation of aquarists towards the same ideals. Authors and Significant Contributors: Barrett L. Christie, The Dallas Zoo and Children’s Aquarium at Fair Park, AITAG Steering Committee Alan Peters, Smithsonian Institution, National Zoological Park, AITAG Steering Committee Gregory J. Barord, City University of New York, AITAG Advisor Mark J. Rehling, Cleveland Metroparks Zoo Roland C. Anderson, PhD Reviewers: Mike Brittsan, Columbus Zoo and Aquarium Paula Carlson, Dallas World Aquarium Marie Collins, Sea Life Aquarium Carlsbad David DeNardo, New York Aquarium Joshua Frey Sr., Downtown Aquarium Houston Jay Hemdal, Toledo -

Eight Arms, with Attitude

The link information below provides a persistent link to the article you've requested. Persistent link to this record: Following the link below will bring you to the start of the article or citation. Cut and Paste: To place article links in an external web document, simply copy and paste the HTML below, starting with "<a href" To continue, in Internet Explorer, select FILE then SAVE AS from your browser's toolbar above. Be sure to save as a plain text file (.txt) or a 'Web Page, HTML only' file (.html). In Netscape, select FILE then SAVE AS from your browser's toolbar above. Record: 1 Title: Eight Arms, With Attitude. Authors: Mather, Jennifer A. Source: Natural History; Feb2007, Vol. 116 Issue 1, p30-36, 7p, 5 Color Photographs Document Type: Article Subject Terms: *OCTOPUSES *ANIMAL behavior *ANIMAL intelligence *PLAY *PROBLEM solving *PERSONALITY *CONSCIOUSNESS in animals Abstract: The article offers information on the behavior of octopuses. The intelligence of octopuses has long been noted, and to some extent studied. But in recent years, play, and problem-solving skills has both added to and elaborated the list of their remarkable attributes. Personality is hard to define, but one can begin to describe it as a unique pattern of individual behavior that remains consistent over time and in a variety of circumstances. It will be hard to say for sure whether octopuses possess consciousness in some simple form. Full Text Word Count: 3643 ISSN: 00280712 Accession Number: 23711589 Persistent link to this http://0-search.ebscohost.com.library.bennington.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=23711589&site=ehost-live -

My Friend, the Volcano (Adapted from the 2004 Submarine Ring of Fire Expedition)

New Zealand American Submarine Ring of Fire 2007 My Friend, The Volcano (adapted from the 2004 Submarine Ring of Fire Expedition) FOCUS MAXIMUM NUMBER OF STUDENTS Ecological impacts of volcanism in the Mariana 30 and Kermadec Islands KEY WORDS GRADE LEVEL Ring of Fire 5-6 (Life Science/Earth Science) Asthenosphere Lithosphere FOCUS QUESTION Magma What are the ecological impacts of volcanic erup- Fault tions on tropical island arcs? Transform boundary Convergent boundary LEARNING OBJECTIVES Divergent boundary Students will be able to describe at least three Subduction beneficial impacts of volcanic activity on marine Tectonic plate ecosystems. BACKGROUND INFORMATION Students will be able to explain the overall tec- The Submarine Ring of Fire is an arc of active vol- tonic processes that cause volcanic activity along canoes that partially encircles the Pacific Ocean the Mariana Arc and Kermadec Arc. Basin, including the Kermadec and Mariana Islands in the western Pacific, the Aleutian Islands MATERIALS between the Pacific and Bering Sea, the Cascade Copies of “Marianas eruption killed Anatahan’s Mountains in western North America, and numer- corals,” one copy per student or student group ous volcanoes on the western coasts of Central (from http://www.cdnn.info/eco/e030920/e030920.html) America and South America. These volcanoes result from the motion of large pieces of the AUDIO/VISUAL MATERIALS Earth’s crust known as tectonic plates. None Tectonic plates are portions of the Earth’s outer TEACHING TIME crust (the lithosphere) about 5 km thick, as Two or three 45-minute class periods, plus time well as the upper 60 - 75 km of the underlying for student research mantle. -

Solar Forcing of Holocene Climate: New Insights from a Speleothem Record, Southwestern United States

Solar forcing of Holocene climate: New insights from a speleothem record, southwestern United States Yemane Asmerom Victor Polyak Department of Earth & Planetary Sciences, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, New Mexico 87131, USA Stephen Burns Department of Geosciences, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, Massachusetts 01003, USA Jessica Rassmussen Department of Earth & Planetary Sciences, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, New Mexico 87131, USA ABSTRACT Holocene climate change has likely had a profound infl uence on ecosystems and culture. A link between solar forcing and Holocene climate, such as the Asian monsoon, has been shown for some regions, although no mechanism for this relationship has been suggested. Here we present the fi rst high-resolution complete Holocene climate record for the North American monsoon region of the southwestern United States (southwest) in order to address the nature and causes of Holocene climate change. We show that periods of increased solar radiation cor- relate with decreased rainfall, the opposite to that observed in the Asian monsoon, and suggest that a solar link to Holocene climate is through changes in the Walker circulation and the Pacifi c Decadal Oscillation and El Niño–Southern Oscillation systems of the tropical Pacifi c Ocean. Given the link between increased warming and aridity in the southwest, additional warming due to greenhouse forcing could potentially lead to persistent hyperarid conditions, similar to those seen in our record during periods of high solar activity. Keywords: Solar forcing, Holocene climate, monsoon, speothem, U-series, southwestern United States. INTRODUCTION beyond the tree-ring chronology, which in the tory1; complete uranium-series chronology data The climate of the Holocene, while relatively southwest only covers the past 2 k.y. -

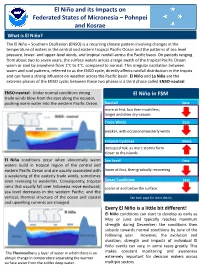

El Niño and Its Impacts on Federated States of Micronesia – Pohnpei And

El Niño and its Impacts on Federated States of Micronesia – Pohnpei and Kosrae What is El Niño? The El Niño – Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is a recurring climate pattern involving changes in the temperature of waters in the central and eastern tropical Pacific Ocean and the patterns of sea level pressure, lower- and upper-level winds, and tropical rainfall across the Pacific basin. On periods ranging from about two to seven years, the surface waters across a large swath of the tropical Pacific Ocean warm or cool by anywhere from 1°C to 3°C, compared to normal. This irregular oscillation between warm and cool patterns, referred to as the ENSO cycle, directly affects rainfall distribution in the tropics and can have a strong influence on weather across the Pacific basin. El Niño and La Niña are the extreme phases of the ENSO cycle; between these two phases is a third phase called ENSO-neutral. ENSO-neutral: Under normal conditions strong El Niño in FSM trade winds blow from the east along the equator, pushing warm water into the western Pacific Ocean. Rainfall Less more at first, but then much less; longer and drier dry-season Trade Winds Less weaker, with occasional westerly winds Tropical Cyclones More increased risk, as more storms form closer to the islands El Niño conditions occur when abnormally warm Sea Level Less waters build in tropical region of the central and eastern Pacific Ocean and are usually associated with lower at first, then gradually recovering a weakening of the easterly trade winds, sometimes even reversing to westerlies. -

Giant Pacific Octopus

A publication by: NORTHWEST WILDLIFE PRESERVATION SOCIETY Giant Pacific Octopus Enteroctopus dofleini Image from the Monterey Bay Aquarium https://www.montereybayaquarium.org By Veronica Pagowski The octopus is an elusive creature with an alien brain. Like humans, these intelligent animals can open jars, recognize faces, and use tools. Yet, only 35% of octopus neurons are located in their brain while 65% can be found in the tentacles. With such powerful, though strangely organized, cognitive systems octopuses have attracted the attention of numerous scientists and aquarists worldwide. The giant Pacific octopus is no exception. Each year, on Valentine’s day, the Seattle Aquarium draws crowds to view giant Pacific octopus mating--an event that can last over an hour. In British Columbia, this species is common enough that divers frequently report sightings. Characteristics The giant Pacific octopus is the largest of roughly 300 known species of octopus, often weighing over 23 kg (50 lbs) with arm spans up to 6 meters (20 feet). The largest recorded weight for this species was over 90 kg (200 lbs). Typically, giant Pacific octopuses are dark red in color with mottled skin, but these animals can quickly change colour or texture to blend in with surroundings. Though giant Pacific octopus colour changes are not as dramatic as the transformations in some other octopus species, colouring can nonetheless range from dark red to white or yellow while skin texture varies from smooth to rugged, flawlessly matching that of kelp or rocks. Each octopus arm can have over 200 suckers- each with the ability to taste, grip, and lift 14 kg (31 lbs). -

Natural Disasters in Latin America and the Caribbean

NATURAL DISASTERS IN LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN 2000 - 2019 1 Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) is the second most disaster-prone region in the world 152 million affected by 1,205 disasters (2000-2019)* Floods are the most common disaster in the region. Brazil ranks among the 15 548 On 12 occasions since 2000, floods in the region have caused more than FLOODS S1 in total damages. An average of 17 23 C 5 (2000-2019). The 2017 hurricane season is the thir ecord in terms of number of disasters and countries affected as well as the magnitude of damage. 330 In 2019, Hurricane Dorian became the str A on STORMS record to directly impact a landmass. 25 per cent of earthquakes magnitude 8.0 or higher hav S America Since 2000, there have been 20 -70 thquakes 75 in the region The 2010 Haiti earthquake ranks among the top 10 EARTHQUAKES earthquak ory. Drought is the disaster which affects the highest number of people in the region. Crop yield reductions of 50-75 per cent in central and eastern Guatemala, southern Honduras, eastern El Salvador and parts of Nicaragua. 74 In these countries (known as the Dry Corridor), 8 10 in the DROUGHTS communities most affected by drought resort to crisis coping mechanisms. 66 50 38 24 EXTREME VOLCANIC LANDSLIDES TEMPERATURE EVENTS WILDFIRES * All data on number of occurrences of natural disasters, people affected, injuries and total damages are from CRED ME-DAT, unless otherwise specified. 2 Cyclical Nature of Disasters Although many hazards are cyclical in nature, the hazards most likely to trigger a major humanitarian response in the region are sudden onset hazards such as earthquakes, hurricanes and flash floods. -

Os Nomes Galegos Dos Moluscos 2020 2ª Ed

Os nomes galegos dos moluscos 2020 2ª ed. Citación recomendada / Recommended citation: A Chave (20202): Os nomes galegos dos moluscos. Xinzo de Limia (Ourense): A Chave. https://www.achave.ga /wp!content/up oads/achave_osnomesga egosdos"mo uscos"2020.pd# Fotografía: caramuxos riscados (Phorcus lineatus ). Autor: David Vilasís. $sta o%ra est& su'eita a unha licenza Creative Commons de uso a%erto( con reco)ecemento da autor*a e sen o%ra derivada nin usos comerciais. +esumo da licenza: https://creativecommons.org/ icences/%,!nc-nd/-.0/deed.g . Licenza comp eta: https://creativecommons.org/ icences/%,!nc-nd/-.0/ ega code. anguages. 1 Notas introdutorias O que cont!n este documento Neste recurso léxico fornécense denominacións para as especies de moluscos galegos (e) ou europeos, e tamén para algunhas das especies exóticas máis coñecidas (xeralmente no ámbito divulgativo, por causa do seu interese científico ou económico, ou por seren moi comúns noutras áreas xeográficas) ! primeira edición d" Os nomes galegos dos moluscos é do ano #$%& Na segunda edición (2$#$), adicionáronse algunhas especies, asignáronse con maior precisión algunhas das denominacións vernáculas galegas, corrixiuse algunha gralla, rema'uetouse o documento e incorporouse o logo da (have. )n total, achéganse nomes galegos para *$+ especies de moluscos A estrutura )n primeiro lugar preséntase unha clasificación taxonómica 'ue considera as clases, ordes, superfamilias e familias de moluscos !'uí apúntanse, de maneira xeral, os nomes dos moluscos 'ue hai en cada familia ! seguir