China's Response to Terrorism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

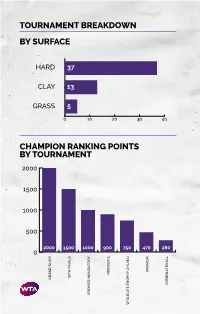

Tournament Breakdown by Surface Champion Ranking Points By

TOURNAMENT BREAKDOWN BY SURFACE HAR 37 CLAY 13 GRASS 5 0 10 20 30 40 CHAMPION RANKING POINTS BY TOURNAMENT 2000 1500 1000 500 2000 1500 1000 900 750 470 280 0 PREMIER PREMIER TA FINALS TA GRAN SLAM INTERNATIONAL PREMIER MANATORY TA ELITE TROPHY HUHAI TROPHY ELITE TA 55 WTA TOURNAMENTS BY REGION BY COUNTRY 8 CHINA 2 SPAIN 1 MOROCCO UNITED STATES 2 SWITZERLAND 7 OF AMERICA 1 NETHERLANDS 3 AUSTRALIA 1 AUSTRIA 1 NEW ZEALAND 3 GREAT BRITAIN 1 COLOMBIA 1 QATAR 3 RUSSIA 1 CZECH REPUBLIC 1 ROMANIA 2 CANADA 1 FRANCE 1 THAILAND 2 GERMANY 1 HONG KONG 1 TURKEY UNITED ARAB 2 ITALY 1 HUNGARY 1 EMIRATES 2 JAPAN 1 SOUTH KOREA 1 UZBEKISTAN 2 MEXICO 1 LUXEMBOURG TOURNAMENTS TOURNAMENTS International Tennis Federation As the world governing body of tennis, the Davis Cup by BNP Paribas and women’s Fed Cup by International Tennis Federation (ITF) is responsible for BNP Paribas are the largest annual international team every level of the sport including the regulation of competitions in sport and most prized in the ITF’s rules and the future development of the game. Based event portfolio. Both have a rich history and have in London, the ITF currently has 210 member nations consistently attracted the best players from each and six regional associations, which administer the passing generation. Further information is available at game in their respective areas, in close consultation www.daviscup.com and www.fedcup.com. with the ITF. The Olympic and Paralympic Tennis Events are also an The ITF is committed to promoting tennis around the important part of the ITF’s responsibilities, with the world and encouraging as many people as possible to 2020 events being held in Tokyo. -

HRWF Human Rights in the World Newsletter Bulgaria Table Of

Table of Contents • EU votes for diplomats to boycott China Winter Olympics over rights abuses • CCP: 100th Anniversary of the party who killed 50 million • The CCP at 100: What next for human rights in EU-China relations? • Missing Tibetan monk was sentenced, sent to prison, family says • China occupies sacred land in Bhutan, threatens India • 900,000 Uyghur children: the saddest victims of genocide • EU suspends efforts to ratify controversial investment deal with China • Sanctions expose EU-China split • Recalling 10 March 1959 and origins of the CCP colonization in Tibet • Tibet: Repression increases before Tibetan Uprising Day • Uyghur Group Defends Detainee Database After Xinjiang Officials Allege ‘Fake Archive’ • Will the EU-China investment agreement survive Parliament’s scrutiny? • Experts demand suspension of EU-China Investment Deal • Sweden is about to deport activist to China—Torture and prison be damned • EU-CHINA: Advocacy for the Uyghur issue • Who are the Uyghurs? Canadian scholars give profound insights • Huawei enables China’s grave human rights violations • It's 'Captive Nations Week' — here's why we should care • EU-China relations under the German presidency: is this “Europe’s moment”? • If EU wants rule of law in China, it must help 'dissident' lawyers • Happening in Europe, too • U.N. experts call call for decisive measures to protect fundamental freedoms in China • EU-China Summit: Europe can, and should hold China to account • China is the world’s greatest threat to religious freedom and other basic human rights -

Trapped in a Virtual Cage: Chinese State Repression of Uyghurs Online

Trapped in a Virtual Cage: Chinese State Repression of Uyghurs Online Table of Contents I. Executive Summary..................................................................................................................... 2 II. Methodology .............................................................................................................................. 5 III. Background............................................................................................................................... 6 IV. Legislation .............................................................................................................................. 17 V. Ten Month Shutdown............................................................................................................... 33 VI. Detentions............................................................................................................................... 44 VII. Online Freedom for Uyghurs Before and After the Shutdown ............................................ 61 VIII. Recommendations................................................................................................................ 84 IX. Acknowledgements................................................................................................................. 88 Cover image: Composite of 9 Uyghurs imprisoned for their online activity assembled by the Uyghur Human Rights Project. Image credits: Top left: Memetjan Abdullah, courtesy of Radio Free Asia Top center: Mehbube Ablesh, courtesy of -

Syllabus(PDF)

Asian Open Dance Tour 2016 Presented by the Asian Dance Council President/ Isao Nakagawa Vice-President/Henry Ooi, David Lee, Soenarko Josodihardjo, Hyo Doo Park, Zhang Xiang Guo Syllabus Date/ February 21, 2016 Tokyo, JAPAN Total Prize Money USD130,600. Event/ 2016 Asian Open Dance Championships in Tokyo, Japan Pro Open B&L/ Organizer/Japan Dance Council/ Junichiro Kusunoki 1st$12,500. / 2nd$9,500. / 3rd$6,500. / E-mail/ [email protected] 4th$3,500. / 5th$2,500. / 6th$1,500. / Venue/ Nippon Budokan 7th- 12th$1,000. Address/ 2-3 Kitanomaru-kouen,Chiyoda-ku,Tokyo102-8321 Pro Closed B&L/ 1st$1,800./ Official Hotel/ Tokyo Prince Hotel 2nd$1,400./ 3rd$1,000./4th $700. / Address/ 3-3-1,Shibakoen, Minato-ku, Tokyo, 105-8560 5th $500. / 6th $400. /7th -12th $200. TEL/ +81 3 3432 1111 FAX/ +81 3 3434 5551 Ama Open B&L/ 1st$4,000./ 2nd$3,000./3rd$2,000./4th$1,800./ 5th$1,500./6th$1,000./7th-12th$500. Date/ February 28, 2016 Taipei ,TAIWAN Total Prize Money USD102,400. Event/ 2016 Asian Dance Tour Taipei Open Pro Open B&L/ 1st$10,000./ Organizer/ Taiwan International Sport Dance Development 2nd$8,000./3rd $ 6,500./ 4th $5,000./ Association/Sammy Liu & Jane Liu 5th$ 4,000./ 6th$3,000./ 7th -12th$ 1200. E-mail/[email protected]/ [email protected] Pro Closed B&L/1st $1,000. Tel / +886 28773-2658 Fax/+886 28773-1169. /2nd$650./ 3rd$450./4th-6th $250. Mobile/ +886 938-186-788 (Jane Liu) Ama Open B&L/1st $1800./ Venue/ Taipei Arena 2nd$1300./ 3rd $800./ 4th- 6th $250. -

Yun Mi Hwang Phd Thesis

SOUTH KOREAN HISTORICAL DRAMA: GENDER, NATION AND THE HERITAGE INDUSTRY Yun Mi Hwang A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2011 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/1924 This item is protected by original copyright This item is licensed under a Creative Commons Licence SOUTH KOREAN HISTORICAL DRAMA: GENDER, NATION AND THE HERITAGE INDUSTRY YUN MI HWANG Thesis Submitted to the University of St Andrews for the Degree of PhD in Film Studies 2011 DECLARATIONS I, Yun Mi Hwang, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 80,000 words in length, has been written by me, that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a research student and as a candidate for the degree of PhD in September 2006; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 2006 and 2010. I, Yun Mi Hwang, received assistance in the writing of this thesis in respect of language and grammar, which was provided by R.A.M Wright. Date …17 May 2011.… signature of candidate ……………… I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of PhD in the University of St Andrews and that the candidate is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. -

In Defense of Cyberterrorism: an Argument for Anticipating Cyber-Attacks

IN DEFENSE OF CYBERTERRORISM: AN ARGUMENT FOR ANTICIPATING CYBER-ATTACKS Susan W. Brenner Marc D. Goodman The September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on the United States brought the notion of terrorism as a clear and present danger into the consciousness of the American people. In order to predict what might follow these shocking attacks, it is necessary to examine the ideologies and motives of their perpetrators, and the methodologies that terrorists utilize. The focus of this article is on how Al-Qa'ida and other Islamic fundamentalist groups can use cyberspace and technology to continue to wage war againstthe United States, its allies and its foreign interests. Contending that cyberspace will become an increasingly essential terrorist tool, the author examines four key issues surrounding cyberterrorism. The first is a survey of conventional methods of "physical" terrorism, and their inherent shortcomings. Next, a discussion of cyberspace reveals its potential advantages as a secure, borderless, anonymous, and structured delivery method for terrorism. Third, the author offers several cyberterrorism scenarios. Relating several examples of both actual and potential syntactic and semantic attacks, instigated individually or in combination, the author conveys their damagingpolitical and economic impact. Finally, the author addresses the inevitable inquiry into why cyberspace has not been used to its full potential by would-be terrorists. Separately considering foreign and domestic terrorists, it becomes evident that the aims of terrorists must shift from the gross infliction of panic, death and destruction to the crippling of key information systems before cyberattacks will take precedence over physical attacks. However, given that terrorist groups such as Al Qa'ida are highly intelligent, well-funded, and globally coordinated, the possibility of attacks via cyberspace should make America increasingly vigilant. -

Viking Voicejan2014.Pub

Volume 2 February 2014 Viking Voice PENN DELCO SCHOOL DISTRICT Welcome 2014 Northley students have been busy this school year. They have been playing sports, performing in con- certs, writing essays, doing homework and projects, and enjoying life. Many new and exciting events are planned for the 2014 year. Many of us will be watching the Winter Olympics, going to plays and con- certs, volunteering in the community, participating in Reading Across America for Dr. Seuss Night, and welcoming spring. The staff of the Viking Voice wishes everyone a Happy New Year. Northley’s Students are watching Guys and Dolls the 2014 Winter Olympics Northley’s 2014 Musical ARTICLES IN By Vivian Long and Alexis Bingeman THE VIKING V O I C E This year’s winter Olympics will take place in Sochi Russia. This is the This year’s school musical is Guy and • Olympic Events first time in Russia’s history that they Dolls Jr. Guys and Dolls is a funny musical • Guys and Dolls will host the Winter Olympic Games. set in New York in the 40’s centering on Sochi is located in Krasnodar, which is gambling guys and their dolls (their girl • Frozen: a review, a the third largest region of Russia, with friends). Sixth grader, Billy Fisher, is playing survey and excerpt a population of about 400,000. This is Nathan Detroit, a gambling guy who is always • New Words of the located in the south western corner of trying to find a place to run his crap game. Year Russia. The events will be held in two Emma Robinson is playing Adelaide, Na- • Scrambled PSSA different locations. -

Military Guide to Terrorism in the Twenty-First Century

US Army TRADOC TRADOC G2 Handbook No. 1 AA MilitaryMilitary GuideGuide toto TerrorismTerrorism in the Twenty-First Century US Army Training and Doctrine Command TRADOC G2 TRADOC Intelligence Support Activity - Threats Fort Leavenworth, Kansas 15 August 2007 DISTRIBUTION RESTRICTION: Approved for Public Release; Distribution Unlimited. 1 Summary of Change U.S. Army TRADOC G2 Handbook No. 1 (Version 5.0) A Military Guide to Terrorism in the Twenty-First Century Specifically, this handbook dated 15 August 2007 • Provides an information update since the DCSINT Handbook No. 1, A Military Guide to Terrorism in the Twenty-First Century, publication dated 10 August 2006 (Version 4.0). • References the U.S. Department of State, Office of the Coordinator for Counterterrorism, Country Reports on Terrorism 2006 dated April 2007. • References the National Counterterrorism Center (NCTC), Reports on Terrorist Incidents - 2006, dated 30 April 2007. • Deletes Appendix A, Terrorist Threat to Combatant Commands. By country assessments are available in U.S. Department of State, Office of the Coordinator for Counterterrorism, Country Reports on Terrorism 2006 dated April 2007. • Deletes Appendix C, Terrorist Operations and Tactics. These topics are covered in chapter 4 of the 2007 handbook. Emerging patterns and trends are addressed in chapter 5 of the 2007 handbook. • Deletes Appendix F, Weapons of Mass Destruction. See TRADOC G2 Handbook No.1.04. • Refers to updated 2007 Supplemental TRADOC G2 Handbook No.1.01, Terror Operations: Case Studies in Terror, dated 25 July 2007. • Refers to Supplemental DCSINT Handbook No. 1.02, Critical Infrastructure Threats and Terrorism, dated 10 August 2006. • Refers to Supplemental DCSINT Handbook No. -

World Uyghur Congress Newsletter No.13 Published: 17 August 2011

World Uyghur Congress Newsletter No.13 Published: 17 August 2011 Newsletter No. 13 August 2011 Official Website of the WUC | Unsubscribe | Subscribe | Older Editions | PDF Version Map: RFA (modified by WUC) Top Story Statement by WUC President Rebiya Kadeer about Kashgar attacks Featured Articles WUC Strongly Condemns New Extraditions of Uyghurs from Pakistan to China Uyghur Refugee Nur Muhammed Turned Over to Chinese Officials by Thai Authorities Media Work UAA Press release on Kashgar Incident International Media Interviews with WUC Leadership Past Events Demonstrations on Hotan Incident in Germany, Austria, Sweden, Turkey and Japan First Action on China-Culture-Year in Germany Uyghur Youth Football Cup Activities by the Japan Uyghur Association on Nuclear Victims in East Turkestan Upcoming Events WUC Organizes Iftar Dinner in Munich 18th Session UN Human Rights Council IV International Uyghur Women’s Seminar 4th International March for Freedom of Oppressed Peoples and Minorities Highlighted Media Articles and reports on Uyghur Related Issues Western companies profit from state development in East Turkestan Article by UHRP Project Manager in OpenDemocracy Security and Islam in Asia: lessons from China’s Uyghur minority USCIRF Calls on China to End Violence and Restrictions in Uyghur Muslim Areas More Media Articles 1 / 9 www.uyghurcongress.org World Uyghur Congress Newsletter No.13 Published: 17 August 2011 TOP STORY Statement by WUC President Rebiya Kadeer about Kashgar attacks WUC , 1 August 2011 The World Uyghur Congress (WUC) unequivocally condemns Chinese government policies that have caused another outbreak of violence in East Turkestan. Without a substantial change to policies that discriminate against Uyghurs economically, culturally and politically the prospect of stability in East Turkestan is remote. -

Dissertation JIAN 2016 Final

The Impact of Global English in Xinjiang, China: Linguistic Capital and Identity Negotiation among the Ethnic Minority and Han Chinese Students Ge Jian A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2016 Reading Committee: Laada Bilaniuk, Chair Ann Anagnost, Chair Stevan Harrell Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Anthropology © Copyright 2016 Ge Jian University of Washington Abstract The Impact of Global English in Xinjiang, China: Linguistic Capital and Identity Negotiation among the Ethnic Minority and Han Chinese Students Ge Jian Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Laada Bilaniuk Professor Ann Anagnost Department of Anthropology My dissertation is an ethnographic study of the language politics and practices of college- age English language learners in Xinjiang at the historical juncture of China’s capitalist development. In Xinjiang the international lingua franca English, the national official language Mandarin Chinese, and major Turkic languages such as Uyghur and Kazakh interact and compete for linguistic prestige in different social scenarios. The power relations between the Turkic languages, including the Uyghur language, and Mandarin Chinese is one in which minority languages are surrounded by a dominant state language supported through various institutions such as school and mass media. The much greater symbolic capital that the “legitimate language” Mandarin Chinese carries enables its native speakers to have easier access than the native Turkic speakers to jobs in the labor market. Therefore, many Uyghur parents face the dilemma of choosing between maintaining their cultural and linguistic identity and making their children more socioeconomically mobile. The entry of the global language English and the recent capitalist development in China has led to English education becoming market-oriented and commodified, which has further complicated the linguistic picture in Xinjiang. -

Ecosystem Service Assessment of the Ili Delta, Kazakhstan Niels Thevs

Ecosystem service assessment of the Ili Delta, Kazakhstan Niels Thevs, Volker Beckmann, Sabir Nurtazin, Ruslan Salmuzauli, Azim Baibaysov, Altyn Akimalieva, Elisabeth A. A. Baranoeski, Thea L. Schäpe, Helena Röttgers, Nikita Tychkov 1. Territorial and geographical location Ili Delta, Kazakhstan Almatinskaya Oblast (province), Bakanas Rayon (county) The Ili Delta is part of the Ramsar Site Ile River Delta and South Lake Balkhash Ramsar Site 2. Natural and geographic data Basic geographical data: location between 45° N and 46° N as well as 74° E and 75.5° E. Fig. 1: Map of the Ili-Balkhash Basin (Imentai et al., 2015). Natural areas: The Ramsar Site Ile River Delta and South Lake Balkhash Ramsar Site comprises wetlands and meadow vegetation (the modern delta), ancient river terraces that now harbour Saxaul and Tamarx shrub vegetation, and the southern coast line of the western part of Lake Balkhash. Most ecosystem services can be attributed to the wetlands and meadow vegetation. Therefore, this study focusses on the modern delta with its wetlands and meadows. During this study, a land cover map was created through classification of Rapid Eye Satellite images from the year 2014. The land cover classes relevant for this study were: water bodies in the delta, dense reed (total vegetation more than 70%), and open reed and shrub vegetation (vegetation cover of reed 20- 70% and vegetation cover of shrubs and trees more than 70%). The land cover class dense reed was further split into submerged dense reed and non-submerged dense reed by applying a threshold to the short wave infrared channel of a Landsat satellite image from 4 April 2015. -

INDIVIDUAL CONSULTANT PROCUREMENT NOTICE Date: July 30, 2021 Reference Number: IC-2021-080

DocuSign Envelope ID: BB6EA17B-538D-4D65-97EA-6E8871B739CA INDIVIDUAL CONSULTANT PROCUREMENT NOTICE Date: July 30, 2021 Reference Number: IC-2021-080 Country: Republic of Kazakhstan Description of the Leader of the expert group for the development of the Scientific Background assignment: report and Feasibility Study for the creation of 5 new PAs1 and a program for monitoring the biodiversity of 5 pilot PAs2 Project name: UNDP-GEF Project "Conservation and Sustainable Management of Key Globally Important Ecosystems for Multiple Benefits", 00101043 Period of August 2021 - December 2022 (250 working days within 17 months) assignment/services: Contract Modality: Individual contractor (IC) Any request for clarification must be sent by standard electronic communication to the e-mail [email protected] and in e-mail subject please indicate Request_Ref.2021-080. 1. BACKGROUND The total forest area in Kazakhstan is about 12.6 million hectares, which makes it one of the richest in forest countries in Eurasia, despite the low level of forest cover, which is only 4.6%. Approximately 95% of the forests (wooded areas) in Kazakhstan are managed by 123 forestry administrations, which are controlled by regional governments (akimats). There are three main types of forest ecosystems in Kazakhstan: alpine mountain forests, tugai (southern coastal) forests and saxaul landscapes (desert and semi-desert shrubs). Since 2018, the GEF-UNDP project "Conservation and sustainable management of key globally significant ecosystems for obtaining various benefits" (hereinafter referred to as the project) has been implemented on the territory of the republic. The project strategy is to holistically address the conservation and sustainable use of forest ecosystems in Kazakhstan, through management approaches including both protected areas and sustainable use of associated HCVF landscapes (maps of the project areas are presented in Appendices 4, 5, 6 to the Terms of Reference).